Posts by FadiHusseini:

The Rise and Fall of ISIS: Regional Dynamics and Global Ambitions

March 8th, 2018Is it the end of DAESH (ISIS)? It is difficult to see how the group could return after the recapturing of Raqqa and Mosul, but the quick rise and apparent fall of ISIS has plagued the region with horrific crimes and mass destruction while planting the seeds of sectarian strife. It can be argued that the chief strategic outcome from the existence of ISIS was that the regional gates were left wide open for global and major regional powers to return and become active. Read the rest of this entry “

Comments Off on The Rise and Fall of ISIS: Regional Dynamics and Global Ambitions

The Price: The end of Iraqi and Syrian Woes and the Vanishing of ISIS

May 11th, 2017By Fadi El Husseini.

![Daesh flag [SpuntnikInt/Twitter]](http://thedailyjournalist.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/2017_3_16-daesh-300x200.jpg) When entangled elements make it hard to reach sound analyses, conspiracy theories appear to be a good tool to explain the unexplained. This applies perfectly to the situation in the Middle East. Many observers are not yet ready to cede their de facto approach, albeit every single regional development shows the clear marks of a crucial role for foreign powers (either super or regional), not only in what has been taking place, but for a debacle that has been erupting in the region for decades, perhaps centuries. Such indicators lead to a strong understanding that dramatic changes might be within striking distance.

When entangled elements make it hard to reach sound analyses, conspiracy theories appear to be a good tool to explain the unexplained. This applies perfectly to the situation in the Middle East. Many observers are not yet ready to cede their de facto approach, albeit every single regional development shows the clear marks of a crucial role for foreign powers (either super or regional), not only in what has been taking place, but for a debacle that has been erupting in the region for decades, perhaps centuries. Such indicators lead to a strong understanding that dramatic changes might be within striking distance.

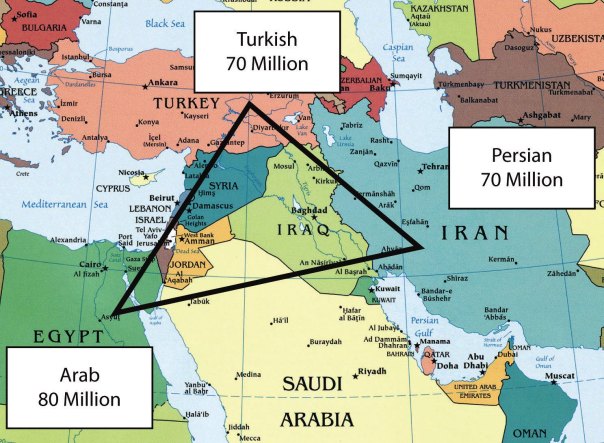

For a start, the unity of the Arabs can’t be benign for foreign powers who have interests in the region. If they were united, they would be a power that won’t let others use them or have imperialist dreams in such a geostrategically-important region. Iran’s growing role in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon is the starkest example of how division, failed-state scenarios and weak governments are nothing but a steppingstone for other powers to sneak in, penetrate and then dominate.

This hypothesis is not limited to the old definition of powers in the form of states; it also includes those novel trans-border actors such as terrorist groups. That said, it should not be surprising to see Al-Qaeda — and then Daesh — appear and flourish in Iraq, following the chaos resulting from the US invasion and occupation. The same concept of chaos and failed-state-scenario applies to Afghanistan, Syria, Libya and Yemen.

History is a good starting point to prove how major powers intervened in this region in order to secure their own strategic interests. The examples are numerous, but perhaps the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement was the most evident case of major powers agreeing to divide the Arab world into competing states. Although the Arabs have never lived in one single state, they have lived in particularly large, interconnected regions such as the Levant (covering what is now occupied Palestine, Lebanon, Syria and Jordan) and the kingdom of Egypt and Sudan (now divided into two states).

Foreign intervention and the fragmentation of the Arabs took a sharper line with the US occupation of Iraq. This occupation not only meant the fall of a state, a president and a dictatorship, or even an end to the Arab nationalism that Saddam Hussein was one of the last Arab leaders to embrace; it also meant a geopolitical earthquake in the whole regional order, with a far-reaching change in the balance of power that prevailed in the Middle East at large. Intriguingly, the collapse of Saddam’s regime meant that Iraq would become prey to Iran. It also meant the stirring up of sectarian strife between the majority of Iraqis who are Shia living for decades under a Sunni ruler, and the minority of Sunnis who were privileged under the Ba’ath regime of Saddam. This ignited the separatist tendencies of the Kurds in the north. The possible repercussions were worthy of much more consideration before the US occupied and then withdrew from Iraq.

History aside, these developments take us to the emergence (or creation by certain powers, if we want to be honest) of a new regional actor known as Daesh. This so-called “Islamic State” presents a bizarre manifestation of an extremely radical interpretation of “Sunni Islam”. Noteworthy in this context is that Daesh did not exist before the US occupation of Iraq and its roots can be traced to Al-Qaeda affiliated Abu Musab Al-Zarqawi in 2004. In response to the chasm of mistrust between the various sects and the immense danger that this group posed, the other sects became more anxious to protect themselves, and at times retaliate. As a result, the role of sectarian militias increased and, to add insult to injury, the separatist tendencies have been justified more than at any time in the past. The calls by Iraqi Kurds for independence have resonated in other countries and encouraged the Kurds in Syria and Turkey to follow suit; we are likely to see another call from Kurds in Iran sooner or later.

Apparently, like their predecessors in the Sykes-Picot era, the superpowers have found that re-fragmenting and re-dividing the region further would better serve their strategic interests. The Kurdish element is critical in the Middle East regional equation, particularly because the separatist tendencies by Kurds in one country have led to others in neighbouring states. In a surprising move, Washington has put its strategic relationship with Turkey at stake with the Trump Administration striking a novel partnership deal with a number of Kurdish groups in Syria.

Walid Faris, who served as Middle East affairs adviser during the Trump election campaign, told Al-Sharq Al-Awsat that Damascus fully acknowledges that the US administration would not allow the regime to move its forces to the east of Syria, neither toward Al-Hasaka nor toward the anti-Daesh combat zones. This, according to Faris, explains why the US dispatched additional US Marines to north-east Syria. In other words, Washington is yearning to become the backbone of the forces that will advance and liberate the swathes of territory controlled by Daesh, the areas over which Washington would not allow the regime to regain control.

Movements in the field lead to a similar conclusion. In fact, with the mounting presence of major powers in the Syrian conflict, these developments show that the role of other actors (militias like Hezbollah, Daesh and Al-Nusra, or states like Iran and Turkey) will come to an end. In other words, such transformations (especially the growing role of the Russian forces) may usher in the end of the Iranian presence in Syria. The departure of the other militias appears to be just around the corner, at least in areas controlled by the Syrian regime. The deployment of the Russian forces near the Lebanese border is a case in point, where Hezbollah’s role has ended, mainly after achieving a demographic change and consolidating a sectarian structure for the various regions inside Syria.

Similarly, the remarkable presence of the US and growing numbers of its troops on the ground has led to parallel scenarios within Sunni areas (currently occupied by Daesh) or Kurdish zones. It looks as if an agreement was reached between the two major powers to divide Syria into spheres of influence based on sectarian or ethnic parameters.

Although Syria was previously an exclusively Russian domain, the significant role and interests of Iran were not always well-received in Moscow. Dividing Syria between Moscow and Washington and eliminating the role of other actors appears to be a win-win situation for the Americans and the Russians. Lest there be any misunderstanding about this outcome, since the outbreak of Arab revolts in 2011, Syria and Bashar Al-Assad himself were not the sole cards held by Russia in the Middle East. Moscow has been developing strategic relations and forging broader interests in several other Middle East states, including Israel, Egypt and even Turkey. On the other hand, it is obvious that the new US administration has a clearer vision on what can be done in Syria, when compared to Obama.

In this context, Dr Faris says that despite the political quarrels, a meeting between President Trump and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin could happen soon. Their publicly agreed upon solution in Syria passes through one gate: the withdrawal of all foreign armed forces and militias, namely Hezbollah, the Iraqi militias, Al-Basdaran, Al-Qaeda, Daesh, Al-Nusra and all of those who reached Syria with the assistance of the Iranian regime. Faris adds that Washington and its NATO allies on the one hand and Russia and its international allies such as China on the other can agree on this solution.

Furthermore, all of those parties also agree that the first stage that can lead to a solution in Syria begins with the “disappearance” of Daesh. Following this, a moderate Arab Sunni authority must assume power in the areas currently controlled by the militants.

The logic behind such a step is that if Daesh is replaced by the Syrian regime – like what is happening in Iraq – this may create a sectarian problem in those areas. Hence, according to Faris, the role of a number of moderate Sunni Arab countries would be important because there is a need for an alliance on the ground, as the US is not ready for a major troop deployment.

We might argue that Syria is thus heading toward a tripartite division: a Russian sphere of influence, wherein the Syrian regime and its Alawi (Shia) Arab sect lives; a US sphere of influence, with the Sunni Arab opposition and its groups; and another US sphere of influence, for the Kurds. Needless to say, we can easily see a mirror image in Iraq, which is mired with sectarian and ethnic traps and a horde of uncertainties, and its divisions are clearer than ever before.

As such, it won’t be outlandish to see the end of the Syrian war soon and in a similar way the disappearance of Daesh, especially after it has almost fulfilled its sinister mandate and purpose for which it was established; that is, the cementing of regional sectarian strife. Daesh can’t have any future in the agreed upon scenario and thus its disappearance becomes inevitable.

Comments Off on The Price: The end of Iraqi and Syrian Woes and the Vanishing of ISIS

Trump and the Palestinian State

December 9th, 2016By Fadi Elhusseini.

Trump’s victory was a real shock, not only for decision-makers in every single capital on this planet, but also to experts and observers who saw nothing but a landslide triumph for the democrats and Hilary Clinton. Shortly after his victory, statements splashed media and political corridors, and Donald Trump himself announced readiness to meet with Israel’s Prime Minister Netanyahu. Many Israeli officials didn’t shy out from saying that the Trump era will be the golden age for the Israeli- American relations and the odds for establishing a Palestinian state become nil.

In Israel, many politicians said they expected Trump to move the US Embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. Israeli Education Minister Naftali Bennett said with Trump’s presidency, there is a chance for Israel to “retract the notion of a Palestinian state.” In fact, with Trump’s victory, the negative repercussions of the so-called Arab Spring and the ongoing chaos in the Middle East served to broaden the clouds of doubt hanging over and led many Palestinian observers to have bleak outlook on the prospects of the peace process and the Palestinian cause in general.

Those observers had reasons for pessimism. During the election campaign, Trump not only committed to moving the US embassy to Jerusalem, but also praised the Republican platform that omits past support for a two-state solution and calls Jerusalem Israel’s “indivisible” capital. Trump and his aides said that Israeli illegal settlements are not an obstacle to peace.

The main pillars of the President-elect’s campaign are staunch advocates and flagrant supporters of Israel and Netanyahu’s policies, such as John Bolton, and Rudy Giuliani, candidates for department of state, not to mention Newt Gingrich, and Michael Pence. Needless to say, Trump has been elected as a representative of a Party that enjoys the majority in the Congress and the Senate. In other words, the administration’s policies will receive support from both legislative institutions.

In spite of those indicators that led to Palestinian’s pessimism, I think it is indeed too early to judge the consequences of the election of Trump and whether this election will lead to a disaster on the Palestinian cause or else for a number of reasons.

First, the Israeli official statements carry a lot of exaggeration especially with regards to the possibilities of establishing a Palestinian state. Those statements are nothing but a psychological attempt that aims to put further pressure on the President-elect in order to fulfill his pre-election promises. This psychological campaign targets as well the Palestinian president at the aim of weakening his moderate front which embarrassed Israel internationally. That being said, I would not have expected different Israeli statements if Hillary Clinton was elected.

Second, regarding the chances of establishing a Palestinian state, it does not depend solely and exclusively on the name of the US president, but rather it is based on more in-depth givens; including the Palestinian dimension itself; internal conditions such as unity and steadfastness in face of the systematic Israeli practices directed to end the Palestinian presence on their land. It also depends on the Palestinian’s resilience and ability to cope with the international turnabouts and regional polarization. It likewise hinges on the international will and desire to end this conflict, and I don’t see that this moment has come yet. It contingent as well on Israel’s readiness to compromise and to accept exchanging peace now with unforeseen future threats in such turbulent region.

Third, it is true that the United States has the most influential role in the peace process, yet old habits die hard. In effect, US foreign policy neither counts on the name of the president nor is subject to drastic changes. US presidents have usually a small margin that allows them to shift slightly away from the broad, well-known and agreed upon lines of foreign policy that are drawn in advance. Perhaps the proximity (of course by a short distance) differs when the president is a Republican or a Democrat.

Although Trump enjoys Congress and Senate Republican majority, two facts should not be overlooked: first is that Trump himself has neither been part of the Republican elite nor its political structure. Until recently, his statements and positions aroused dissatisfaction and dismay by many traditional Republicans. Second is the importance of the role of the deep-state which has been setting up aforementioned broad lines of US policy.

At this juncture, one can say that the most critical challenge would be Trump’s ability to maneuver and distance himself from traditional US foreign policy broad lines. If he succeeds, this would constitute an unprecedented case in US decision-making history.

Any change in US traditional foreign policy broad lines will be evident not only on the Palestinian-Israeli conflict but also on the entire Middle East. If this to happen, it will usher a period of uncertainty in international affairs. In other words, a change that would reach other regions and will eventually have an impact on the whole US international relations network. By then, US relations with traditional allies and friends will be affected and the entire web of international relations may witness a revolution.

Perhaps the conjuring question would be: Can Trump match words with deeds? In other words, can Donald Trump move the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem? Many US presidents said they would do during their campaigns, but when they took office they realized that such a decision contradicts with US traditional foreign policy broad lines. If Trump does so, then this would a fundamental turning point and a significant sign for unprecedented deviation from traditional US foreign policy.

Preliminary indications show that realpolitik comes to the fore and Trump will not stray far from known axioms of American foreign policy. His recent statement that he will work to reach a peace agreement between the Palestinians and the Israelis confirm that he has already begun reading the White House brochure for new presidents.

In a word, pragmatism asserts its rights. While it may be early to make judgments, it is crucial to admit that a Palestinian state is part and parcel of the internationally recognized two-state solution: the state of Israel and the state of Palestine. Any US president who is eager to see a more stable Middle East must work on making this solution achievable. Disregarding the realistic demands of either party would lead to more degradation of this solution and would eventually put the last nail in the coffin of the already-waning Middle East Peace Process.

A previous version appeared on: http://www.eastonline.eu/en/opinioni/open-doors/trump-palestinian-state

Comments Off on Trump and the Palestinian State

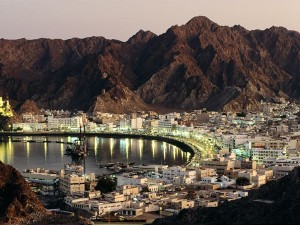

Oman: a Peaceful Oasis in a Flaming region

May 22nd, 2016In a fractious, unstable region rife with conflicts, one country appears to be unscathed. It is telling that Oman emerged not only intact from the ramifications of the Arab Spring, but also shied away from the tense polarisation that has hijacked the rest of the Middle East. Oman’s position on the various regional issues is self-evidently peaceful and different from the other Gulf monarchies. In fact, behind this peaceful and unique position lies a hive of activity of which many are unaware. Read the rest of this entry “

Comments Off on Oman: a Peaceful Oasis in a Flaming region

Putin’s “Completely Fulfilled” Task in Syria

March 24th, 2016By Fadi Husseini.

Since Russia has been declared officially in the Middle East, and following the extended presence of its military in all forms in Syria, speculations splashed media platforms across the globe. Observers saw in Russia’s decision to enter Syria a long-term strategy, albeit the abrupt announcement of Russian President Vladimir Putin to withdraw most of the Russian forces from Syria put friends and foes alike in bewilderment.

Putin ordered a pull out of “the main part” of his troops in Syria and the exact words he uttered to his defense minister Sergey Shoigu were “The task presented to the defense ministry and the armed forces has been completely fulfilled.” Examining the avowed goal for Russia’s operation in Syria six months ago is a stepping stone in analyzing what “task” Putin is talking about. Fighting and destroying ISIS after the US-led campaign proved to be an “abject failure” was the primary goal and taking a pre-emptive move to abort any efforts to export those radicals back to Russia was the secondary goal. Nonetheless, neither ISIS nor al-Nusra were defeated and Moscow has no solid evidence that those terrorist groups lost ability to send their radicals back to Russia.

Accordingly, Putin’s recent remarks refute the declared goal in the first place. This conclusion takes us to the other expected birds Russia was aiming to kill with one stone- which is the intervention in Syria. Among the various goals Russia was aspiring from this intervention were bolstering Russia’s military- and hence strategic presence- in the region, preventing the fall of Assad and balancing the military operations on ground, dictating its political will on any future regime, neutralizing the mounting Iranian leverage on Syria and weakening Assad’s rivals. Apparently, throughout the past six months Moscow was able to relatively realize most of the aforementioned goals.

Strategic presence in the region

Russia proved to be a key player and a significant element in the Middle East equation and the Syrian issue in particular. Militarily, while much of the equipment and manpower were being loaded out, Moscow emphasized that the Russian airbase in Hemeimeem and a naval facility in the Syrian port of Tartus will continue to operate. ARussia indicated that the advanced S-400 air-defense system, three Sukhoi Su-34 combat aircraft and a Tu-154 transport plane, would stay in Syria, and experts expect that air force and naval assets also will be left behind. After all, Moscow was able to reinforce the strategically important military base in Tartus and founded a new one. Thus, Russia was able to not only secure a solid footprint in the Middle East and overcome the international isolation brought about as a result to its intervention in Ukraine, but also to extend its political sway.

The Political Solution in Syria

Russia’s intervention turned the tide of war and tipped the balance of the combat operation back towards Assad. The Western-backed “moderate” opposition was weakened and Assad forces began to regain lands that they lost before the Russian intervention. Consequently, Russia asserted itself as the pioneer of this new political process. Brokered by Russia and the US, a ceasefire with Assad still in power was forced and diplomatic efforts stepped up to secure peace deal negotiations. One must concede thus that Russia was able to maneuver itself into a position of real leverage and to include Assad and his regime in any peace talks. Meanwhile, Iran’s role in these peace talks appears marginal when compared to Russia and this fulfils another unspoken goal by Moscow.

The timing of Moscow’s announcement

Some Arabic media channels contended that differences of opinion between Putin and Assad led Putin to shortly announce the pullout plans. Differences, according to these channels, arouse from Assad’s talks to re-control the entire country that may ruin any potentials for a political solution. Some other Arabic sources suggested that Putin’s decision comes in light of the mounting ‘Sunni’ dismay from Russia’s plans in backing Assad, who is Alwai-Shiite. Both arguments can be true, yet they neither answer the crucial question “why now” nor assume that Putin had these calculations before the outset of his operation.

Perhaps the answer is a confluence of all various considerations, yet the key word is the peace talks. Russia had limited objectives in remaining long in Syria. According to Reuters, the Russian campaign has cost Russia nearly $800 Millions. With Russia’s economy under sanctions, Moscow is fully aware that it cannot afford to sustain a long-term combat operation in Syria. Thus, the goal was to realize the strategic objectives (defeating the capacity and capability of Assad’s rivals and providing him with a better position in the negotiations) in due time and then begin redeployment.

From day one, Russia was looking for an exit strategy. With Assad’s improved position on the ground, a NATO intervention option no longer possible and the launching of a serious political process, Moscow seized its moment. Russia’s ally has negotiates from a position of power and in case the peace process produces tangible results, Russia alleviates itself from any future commitments. Hence, Russia’s goal was operational and not to delve into a nation-building operation.

Moreover, Moscow aims to evade any conflagration with Turkey (in case the latter plans to intervene in Syria) and focus more on the Ukrainian issue. The timing of Moscow’s announcement was hugely significant especially when it is in need for more allies that can back its position in Ukraine. Russia’s decision sent positive signal and was warmly welcomed by many countries, mainly Arab State. This would ultimately help Russia to repair relations with the Sunni states who criticized the Russian intervention in Syria.

Conclusion

So far, imaging that Russia will abandon Syria is unrealistic and thus Moscow’s decision is purely tactical and timely. After securing a foothold and loyal ally, Putin used the first opportunity to begin withdrawing his troops whose mission was deemed to be limited in scope and time. Nevertheless, the only element that has been missing and playing no role in the Russian and others’ considerations is ISIS and the fight against terrorism.

Comments Off on Putin’s “Completely Fulfilled” Task in Syria

The Middle East: Was the Turkish Model replaced by an Iranian Role?

March 9th, 2016By Fadi El Husseini.

Since 2003, Turkey has appeared as a valuable asset for global powers to invest in and as a leading actor in a region long described as sluggish towards democratic transformations. However, with the advent of the Arab Spring, things changed and the role portrayed for Turkey by the United States has been declining, especially in light of the rise of another regional power: Iran.

The United States sought to endorse the Middle East Partnership Initiative, which became the Greater Middle East Initiative (GMEI) in 2003. America’s efforts did not stop at the GMEI, and it offered yet another project coined the “new Middle East”. The avowed goal of these initiatives was to encourage political, economic and social reforms in the region, based on a vision to improve America’s image in the Middle East, which had been greatly smeared and distorted as a result of the US invasion of Afghanistan and occupation of Iraq.

Seeking a new model that could be acceptable to Arabs and was far from the images and stereotypes of the old, traditional regimes thus became a must. This idea gained more momentum after the Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power with Turkey’s parliamentary elections of 2002, and a new project for the democratization of the Middle East became a viable option.

The rise of the AKP was the answer. It shifted the compass in the direction of moderate Islam at a time when this concept in general and the Turkish model in particular, struck a deep chord with dissatisfied public averse to corrupt regimes. And it became a priority.

Turkey thus became a crucial element in these projects and was deemed a model for moderate Islam. The United States recognized its qualities and designated a leading role for the country for its geostrategic location, long-time record as a Western ally, extensive democratic experience and its emergence as a nation that successfully combined Islamic and Western values.

These principles comprised the core of what came to be known as the Turkish model. This model underlined the background of the ruling AKP, which originated in Islamist tradition but claimed to merge that tradition with modernism and liberal democracy.

The Turkish model then splashed across media and academic platforms. It became part of Arabs’ lively daily debates, and Arab thinkers and intellectuals encouraged their rulers to emulate it. Many aspects helped the model’s prominence rise and flourish within Arab societies.

In addition to US efforts to propagate Turkey’s status as a representative of moderate and democratic Islam, the Islamic background of its ruling elite, its economic success, balanced relations with the East and West, military might and NATO membership have all put the Turkish model on track.

However, revolts do not come knocking on the door. They sneak in, changing chartered paths and dealing blows to strategic plans. With the outbreak of Arab revolts, the stable environment (the Arab world) upon which Turkish decision-makers built their strategies changed and became uneven. At first, most observers thought the Arab Spring would be a historic opportunity for Turkey to further endorse its status in the region. Yet things changed and Turkey’s popularity has been declining with each passing year.

In subsequent polls since 2011, Middle Easterners have proved lukewarm towards Turkey’s role in the region. Year by year, this tepid reaction has increasingly transformed into aversion and suspicion. Even in official circles, Turkey’s relations with several Middle Eastern countries have been tainted with tension and, at times, hostility.

Meanwhile, whether one likes it or not, Iran has been moving slowly but steadily towards an extraordinary status and role in the Middle East. The country began emerging from decades of isolation after the nuclear deal helped its economy and propelled it back into the world.

It started formulating this role a long time ago, and the deal was just a stepping stone. Iran has been employing an ever-widening array of instruments to build strategic partnerships and alliances throughout the Muslim world and beyond. One of its most successful tools is soft power, which includes media, assistance and aid, and cultural ties. The country also used trade and investment to further penetrate the region. Iran Chord is a salient example: the state-owned company has emerged as the largest carmaker in the Middle East, exporting over one million vehicles in 2007.

Recently, Iran signed agreements with Afghanistan and Tajikistan to build railroad and power lines linking Iran and the Central Asian republics, as well as China and Russia. Furthermore, Iran is politically and militarily cooperating with Russia in Syria with the aim of securing Moscow’s support in numerous spheres. One of which is Iran’s attempt to join the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) as a full member. Iran was accepted as an observer state, yet full membership would secure further strategic support from Russia and China.

More so, Iran’s extended leverage in the region has always been demonstrated in a network of allies that has been expanding to include more members. The main logic behind this network lies in Iran’s soft power and its ability to export both revolutionary values and Shiite fraternal connections.

Iran was adept enough to promote itself as revolutionary hub and an address for all those who aim to fight foreign imperialism. The eventual result was the formation of the “resistance axis” to encounter the “moderation axis” which encompasses US allies in the region.

Iran was adept enough to promote itself as a revolutionary hub and a home for all those aiming to fight foreign imperialism. The eventual result was the formation of the ‘axis of resistance’ to counter the Arab ‘moderation axis’ that encompasses US allies in the region.

In addition, Iran’s connections with Shiite communities in Iraq, Bahrain, Yemen, Eastern Saudi Arabia and Lebanon demonstrate the success of its soft power. The number of Shiite visitors to Iran is proof of this success. According to 2013 figures, roughly four million tourists visited Iran: the majority was religious Shiite or medical tourists while some one million were regular tourists.

Iran further expanded its network beyond traditional state actors such as Syria and Iraq to include non-state actors and groups such as Hamas and Jihad in Palestine, Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen. Iran was pragmatic enough to also establish relationships with seemingly unlikely partners such as China, Russia, Turkey, India, Nicaragua, and Algeria; and to sign scores of agreements in the fields of hydrocarbons and energy, and trade and transport.

Inter alia, of the various elements that weakened the Turkish model was Iran’s mounting leverage in the Middle East and the Arab Spring, which delivered a blow to Turkey’s achievements as Iran was moving slowly but steadily towards a status it carefully charted. Then came the nuclear deal, which boosts Iran’s potential in the region and has intriguingly raised a third perspective: have Arabs surrendered their aspirations to play a role in their region? Although the Islamic coalition declared by Saudi Arabia seems promising, this idea has not been translated into practical steps, nor does a united Arab position seem in the offing. The diverse Arab positions on how to respond to Iran’s recent attacks on the embassy and consulate in Saudi Arabia are a case in point.

This article was first published by: Eastwest magazine: http://www.eastonline.eu/en/eastwest-64/if-tehran-now-competes-with-ankara

Available in: Arabic, French and Italian

Comments Off on The Middle East: Was the Turkish Model replaced by an Iranian Role?

Russia is Officially in the region: A new Order has just begun

January 4th, 2016

By Fadi Elhusseini.

Since the outbreak of the Syrian uprising, Russia has limited itself to its traditional role of providing arms as well as military and logistical experts to its Arab allies. As Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime weakened, the Russians intensified their military support dramatically. Recently, the Russian ‘Caesar’ opted to expand his role in Syria to include direct intervention against enemies of the regime. The move towards direct intervention constitutes a revolution in Russia’s role in the Middle East and portends a deeper shift in the region.

Russia has claimed that its intervention in Syria was intended to destroy IS after the US-led campaign proved to be an “abject failure”, according to an unnamed US military official speaking to CBS News. Well acquainted with terrorism, one might argue that Moscow is undertaking a pre-emptive war against Islamic extremist groups. But some have linked the intervention to the Ukrainian crisis as well as the desire for increased leverage in the Middle East and more power at the negotiating table.

Thus Russia’s stated intentions have been met with skepticism about the real motive behind the decision to intervene directly. One widespread opinion is that Russia wants to secure a military presence on warm- waters – the Mediterranean Sea. While this sounds plausible, Russia has been enjoying this presence for some time already. Warm-water ports are of great geopolitical and economic interest and they are the ports where the water does not freeze in wintertime.

Those ports have long played an important role in Russian foreign policy. The Russian Empire fought a series of wars with the Ottoman Empire in a quest to establish a warm-water port. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of World War I didn’t give Russia any further control. The Soviet Union enjoyed access to naval bases throughout the Mediterranean, yet its collapse brought an end to that access, except for the base in Tartus in Syria. Since 1971, Russian naval has had presence in Tartus and with Russia’s recent intervention, this port enjoyed unprecedented fame.

So what really lies behind the dramatic shift in Russian foreign policy?

In fact, Russia’s recent direct intervention in Syria gave a goodbye kiss to the conventional regional order that ruled the Middle East for ages. Traditionally and even at the peak of the Cold War, Russia’s (either the Soviet Union or the Russian Federation) role was limited to sending arms, military and logistical experts to its Arab allies. The current intervention constituted a revolution in Russia’s role and marked an extraordinary heavy military intervention.

The recent Russian intervention coincided with a number of important events. First is the Iranian nuclear deal which gives Iran a more prominent regional role, especially when considering the economic potentials this deal left Iran with.

Second is the US gradual withdrawal from the region, which was symbolized in the withdrawal of its troops from Iraq, handing over Iraq’s destiny to the Iranians, cooling off efforts in the Palestinian- Israeli conflict that led to the emergence of other initiatives (e.g. the French, the New Zealand), and finally its decision to withdraw the defensive shield from Turkey (for technical reasons according to the US announcement). Giving up its historical allies in Egypt (Mubarak) and Tunisia (Ben Ali), in addition to leaving the Saudis and the Gulf to fight Iran’s influence in Yemen alone are other signs of US declining role in the Middle East.

A few years ago, the president of the US Council on Foreign Relations, Richard N. Haass, wrote that the era of the United States’ domination in the Middle East was coming to an end and that the region’s future would be characterized by reduced US influence. Many observers do not believe the US will voluntarily abandon its role in the region, but the actions of other nations, combined with the Russians’ plans in Syria, clearly point in this direction.

Under the slogan «fight against terrorism», China sent aircraft carrier “Liaoning-CV-16” to Tartus and sources revealed that Beijing is heading to reinforce its forces with “J-15 Flying Shark” jets and “Z-18F & Z-18J” helicopters equipped with anti-submarine, in coordination with Tehran and Baghdad. France and Britain followed suit; the latter announced that it would mobilize reinforcements and military capabilities to the Mediterranean and Paris said it would send “Charles de Gaulle” aircraft carrier to participate in operations against ISIS in addition to six Rafale Jets in the United Arab Emirates and six Mirage aircraft in Jordan.

For its part, the US, whose aircraft carriers have been absent from the region since 2007, ordered a mere 50 special operations troops to Syria in order to help coordinate ‘local’ ground forces in the north of the country. US President Barack Obama condemned Russia’s direct intervention strategy, saying it was “doomed to fail”. And yet in a press conference in August 2014, he acknowledged that the United States “does not have a strategy” in Syria.

Media talks aside, Washington cannot have been taken by surprise when the Russians commenced their operations in Syria. Assuming that the Obama- Putin summit, which came hours before the Russian earliest move in Syria, did not tackle Russia’s intervention plans, there were many clues that prove US prior knowledge of Moscow’s decision.

In July 2015 Iranian Major General Qassem Soleimani visited Moscow to coordinate the Russian military intervention and thus forging the new Iranian-Russian alliance in Syria. According to a Reuters report, Soleimani’s visit was preceded by high-level Russian-Iranian contact and meetings to coordinate military strategies. Two months later, Iraq, Russia, Iran and Syria agreed to set up an intelligence-sharing committee in Baghdad in order to harmonize efforts in fighting ISIS.

A senior US official confirmed on 18 September that more than 20 Condor transport plane flights had delivered tanks, weapons, other equipment, and marines to Russia’s new military hub near Latakia in western Syria, followed by 16 Russian Su-27 fighter aircraft, along with 12 close support aircraft, four large Hip troop-transport helicopters and four Hind helicopter gunships. Hence, it is clear that the US administration was at least aware of the Russian massive preparations and yet opted to keep its presence to the minimum. In this vein, it can be strategically said that this decision goes in line with the aforementioned US grand plan in the region and marks a calculated strategic gain when securing a small share in a Russian traditional sphere of influence: Syria.

The stated Russian motivation behind this involvement does not match for the facts on the ground. In other words, fighting ISIS, who does not have fighter jets or missile defense systems, does commensurate neither with the sophisticated air defenses that the Russians installed at the “Humaimam” base (such as SA15 and SA22 surface-to-air missiles) nor the Russian announcements that 40 naval “combat exercises” were due to start in the eastern Mediterranean, including rocket and artillery fire at sea and airborne targets. For that reason, some other experts found in Russia’s intervention as part of its new maritime strategy, that was publish on 26 July 2015. The new maritime doctrine of the Russian Federation to 2020 is a comprehensive state policy for governing all of Russia’s maritime assets, military fleets, the civilian fleet, merchant marine, and naval infrastructure.

Russia therefore might be looking to kill as many birds as possible with one stone. Moscow will first and foremost dictate its political will on any future solution in Syria and the inclusion of Iran and Russia in Vienna talks is just a case in point. Better, Secretary of State John Kerry now concedes that the longtime Russia’s ally Bashar Al-Assad might indeed be allowed to retain power for a period, Germany’s Chancellor, Angela Merkel said that the West will have to engage with Assad if it is to have any chance of resolving the Syrian civil war and the British indicated a similar shift in policy. Second, Russia has now guaranteed a bigger role in the formation of a new Syrian government, even if Assad is pushed out of power and any nascent regime would seriously consider Russia’s role and presence in the country; including military, investment and commercial interests (e.g. in 2011 Russia invested $19 billion in Syria).

Third, Russia is underway to expand its military presence; not only in Syria, but also in the region and the announced intelligence sharing agreement demonstrates this goal. For example, Russia offered a large array of military hardware to Iraq (such as military helicopters in 2013 and Su25s fighter aircraft) that the US has refused to sell. Fourth, although it looks like Russia and Iran have a common goal in Syria, Russia’s blatant involvement ceased Iran’s monopoly over the Syrian file. Fifth, Russia is making pre-emptive war against Islamic extremist groups from which Russia has long suffered. Russia can’t tolerate the return of Chechens or other fighters who joined ISIS and is concerned that the West may use those radicals against Russia in a similar scenario to the Afghani case.

Sixth, the Russian intervention came amidst confirmed military sources that the longtime Russian ally – the Syrian regime – is about to fall when it controlled only 18 percent of the country and its army exhausted 93 percent of the stock. Seventh, the mounting leverage of Russia in the region will give Russia a bigger seat at the Ukrainian negotiations table. Finally, Russia aims at the revival of its military industries market as it was able to promote itself as an international player that can be relied upon to contain Iran, to prevent the Syrian regime’s use of chemical weapons, to contribute actively in the fight against terrorism, and to sell technologies for peaceful energy in the Middle East. For example, the Russian Defense Ministry is working currently on major deals with Gulf Arab states in order to develop the Marine Corps, and air defense systems, techniques of unmanned aircrafts, armored vehicles and signal systems. Russia is now building two nuclear facilities in southern Iran and in February Russia agreed to build nuclear reactors in Egypt. Moscow is negotiating as well with Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait and Jordan for deals to develop nuclear power, the largest deal was on 19 June 2015 when Moscow agreed to establish 16 nuclear reactors in Saudi Arabia.

In short, Russia must now be taken seriously as a major player on the Middle East scene. The Russian recent intervention is Syria was not the first move in that direction and regional powers have reached the same conclusion even before. That said, it was not outlandish to see that Middle Eastern leaders visiting Moscow in no time.

A previous version of this article appeared originally at: http://www.eastonline.eu/en/eastwest-63/world-outlook-a-new-regional-order-arises

Comments Off on Russia is Officially in the region: A new Order has just begun

ISIS: Ambitions and Constrains

November 22nd, 2015By Fadi El-Husseini.

Since its inception, news of Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS/Daesh) has splashed across the world’s media. The nascent entity emerged suddenly and expanded quickly. Its brutality has commanded widespread attention and generated mounting concern. A few months ago, Daesh entered its second year, demonstrating a unique ability to survive despite being targeted by joint international efforts and military campaigns. This article digs deep inside the life of Daesh, assesses important details such as its structure and formations and highlights facts that may be important to the general reader and decision-maker alike. These features reveal the complexity of the composition of Daesh which it has managed to build in record time. Read the rest of this entry “

Comments Off on ISIS: Ambitions and Constrains

The Middle East: Rising and Falling Start

October 29th, 2015By Fadi El-Husseini.

In 2011, Turkey was seen as an unstoppable regional power and a rising star led by its Development and Justice Party (AKP). But the arrival of the Arab Spring heralded a deep change in the region. Turkey’s prominence began to fade and Iran’s potential appeared to be rising with the progress it is making in nuclear negotiations. Further developments in the region have continued to surprise observers, especially the emergence of the ascendant force that is the Islamic State (IS).

Until the Arab revolts began, many believed Turkey would enjoy a bright future as a leader in the region under the AKP. Most Arabs were eager to emulate the Turkish model of democracy and economic success. Many politicians established and named their parties after the ruling AKP, and Turkish products and soap operas were flooding Arab markets and homes.

With his charisma and rhetoric, former Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was seen by most frustrated Arabs as a saviour, a leader who cared for his neighbors and had qualities their own dictators lacked – especially his open opposition to Israeli policies and practices against the Palestinians. Nonetheless, as the Arab Spring continued, a shift began to take place.

Turkey lost territory in Syria, upset the Gulf nations, further strained its luke warm relations with Iraq, entered into conflict with Israel and finally saw its relations with Egypt deteriorate. And Turkey’s challenges did not end at its doorstep. With the Gezi Park protests in Istanbul and the 2013 corruption scandals involving a number of AKP ministers, the problems turned out to be domestic as well.

The recent elections in June could be considered the biggest blow suffered by the Turkish AKP since its inception in 2001 – 13 years of single-party rule in Turkey have come to an end. And while the AKP had provided Turkey with political stability and economic recovery, the impact of the recent elections on Turkey’s domestic politics and foreign policy will have direct repercussions across the entire region.

Meanwhile, as Turkey’s regional star is setting, other stars are rising. Iran, for example, is a regional power with considerable potential. Its closest allies in the region (the Assad regime in Syria, Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Huthi in Yemen) have been under tremendous pressure, and their power and leverage has been declining significantly. But although Iran has suffered a great deal since the advent of the Arab Spring, the nuclear deal reached with the 5+1 nations will bolster its position over time by lifting decades-long imposed sanctions. It will furthermore allow Iran to export its oil again (the re-emergence of such a huge exporter will undoubtedly hurt Russia’s economy) and will eventually lead to unfreezing many more of Iran’s assets – in 2014 the US unfroze $1 billion, or €913 million.

If this happens, there is no question that Iran, which could build a network of regional allies and preserve its military capabilities with an immense arsenal of weapons, will become a rising economic power as well. As such, one can expect Iran’s allies, mainly Shiite groups, to receive a big boost as well.

A remarkable third player has been emerging on the Arab stage: the nonstate actor, IS. The group arose from the remnants of dissolved regimes, failed dictatorships, and an austere interpretation of Islam, and has imposed and reinforced its presence and influence across the region. The emergence of IS has turned the whole region on its head. Puritanism has swept the Arab world and a new vocabulary – one of apostates, infidels and heretics – has become commonplace. In the blink of an eye, IS was able to eliminate borders and take control of large swaths of Iraq and Syria.

The 60-plus members of the USled anti-Islamic State coalition have been unable to stop IS expansion and the consolidation of its rule. Interestingly, US President Barack Obama announced in July that he believes there is no end in sight to the battle with IS, meanwhile stressing that he opposes putting any more US boots on ground.

IS can be understood as a unique representation of the entangled interests and relations in the region. Through IS, some powers aim to weaken Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime and his closest ally in Lebanon, Hezbollah. Others are eager to use IS to keep the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) busy and distracted. A third group is interested in IS sparking a sectarian conflict that would drag both Sunni and Shiite extremists into an endless war so as to ‘let the bad guys kill each other’.

US Vice President Joe Biden even accused America’s key allies in the Middle East of allowing the rise of IS and supporting it with money and weapons in order to oust the Assad regime. Biden summed up the crux of the issue in his speech at the John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum: “(US allies) were so determined to take down Assad and essentially have a proxy Sunni- Shia war”.

Similarly, US General Wesley Clark stated that “ISIS got started with funding from our closest allies … to fight to the death against Hezbollah”.

With the current state of affairs, and in light of the recent elections, one can conclude that Turkey’s foreign policy influence and regional leadership role will decline. The AKP, which in the eyes of many Western countries represents a moderate model of Islamic democracy, can no longer form a single- party government and will thus lose the leverage and freedom to execute the kinds of proactive policies it had previously championed in the Middle East. The decline of Turkey will result in the strengthening of other regional forces: Iran and IS. As outlined above, the promising potential of Iran in the region will mean a new role for the country and perhaps a fresh network of Shiite allies. Meanwhile, the clout and influence of the mighty IS – which adheres to a strict Sunni dogma – is steadily growing.

Unfortunately, these developments can only lead to only one conclusion: an unavoidable, far-reaching, Sunni-Shiite conflict.

(This article was first published by East Magazine www.eastonline.eu)

Comments Off on The Middle East: Rising and Falling Start

Palestine: Time to decide!

September 28th, 2015By Fadi El-Husseini.

On August 27th, headlines splashed global newspapers that Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas and nine other top officials resigned from the ruling Executive Committee (ExCo) of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). Talks about an emergency or a regular session of the Palestine National Council (PNC) followed. Although PNC Chairman Salim al-Zanoun announced Sept. 14-15 PNC meeting in the West town of Ramallah, few days ago al-Zanoun announced postponing the meeting for three months. These developments raised many questions; the most important is what the actual reason behind convening this meeting in the first place.

In fact, observes were wondering if Abbas is really quitting, or if it is a tactical move to shake stagnant water. It is worth clarifying that although the news suggested that the resignations were final, the mater of the fact is that they’re not official. PNC Chairman Salim al-Zanoun said he received a letter from Saeb Erekat, the new secretary general of the ExCo, stating that the ten members “vowed to resign”. Thus, it is a promise and elections will replace only the ten.

Technicalities aside, realities brought attention to the upcoming parley. First and foremost, the PNC congress- a 776-seat parliament-like body representing Palestinians in the West Bank, the Gaza Strip and the diaspora- convenes for the first time in nearly 20 years. Second, it comes amid fierce domestic quarrels in the PLO’s largest factions _ Fatah on the side and between Fatah and the militant Hamas, on the other. Furthermore, the meeting follows discharging the former ExCo secretary general, Yasser Abed Rabbo, who was widely accused as being anti-Abbas.

One must concede, however, that convening the congress is on its own an accomplishment. Now, whether the meeting aims to serve certain political goals by one party or another, it will definitely usher a new beginning as it seeks to reorganize a languid body that many Palestinians see as helpless.

Aside from any PLO domestic issues, the relationship with Israel, deadlocked peacemaking, the fallout of reelecting Israeli Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu and the hardest-line right wing religious Cabinet ever, and the tepid US dealing with the Palestinian cause, shadow the agenda of the upcoming parley. These issues were reflected in a recent decision by the Palestine Central Council (PCC), a significant 124-member body that liaises between the PNC and the ExCo, to review political, economic and security relations with Israel.

In the same context, the Saudi Watan Newspaper said on Sept. 10th that Abbas will declare before the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) on Sept. 30th reviewing relations with Israel at all levels. Having said this, with Abbas’s ultimate frustration with the Israeli-slapped status-quo, the upcoming meeting may discuss the possibility of dissolving the Palestinian Authority (PA) and instead forming a new government-in-exile.

The idea has been floated in Palestinian circles, considering that Israel stripped the PA literally of all authority it commands. The recent decision by the Israeli high court to demolish Palestinian houses in areas A (which are under the control of the PA) is just a case of point. This decision was interpreted by PA as an official Israeli declaration of the death of the Oslo peace accords between the PLO and Israel

According to the Palestinian narrative which relies on Geneva conventions, if the PA is dissolved, Israel must shoulder the responsibility of the people and the lands it occupies, as it did before the PA emerged in 1993. Thus, Israel will pay a high cost and, in that case, it will feel the pinch of its prolonged 48-year occupation, the longest ever in modern history.

Time is ticking; three months separate the date to the upcoming PNC meeting where the Palestinian leadership is expected to take fateful decisions. When the Israeli government fails to act in order to save peace, here exactly comes the real responsibility of the international community.

Another version is also available in French

Comments Off on Palestine: Time to decide!

Hamas Diplomatic Activism: Modified Strategies and new alliances

September 8th, 2015By Fadi El-Husseini.

Many observers saw a potential breakthrough in Tony Blair’s recent meeting with the head of Hamas’ political bureau Khaled Meshaal that may take Hamas out of the bottleneck and lead to a long-term truce between the movement and Israel. Yet, it appears that the crux of the issue surpasses initial assessment as this meeting comes in the midst of entangled developments and may perhaps lead to various domestic, regional and global transformations. Read the rest of this entry “

Comments Off on Hamas Diplomatic Activism: Modified Strategies and new alliances

The Arab Spring and the Rise of non-State Actors

June 24th, 2015

By Fadi El-Husseini.

In the past four years, Arabs have been living in an endless Sisyphean ordeal, an unexpected nightmare after rising for what they called “the Arab Spring”. The scenario was cloned in most Arab Spring countries. Alas, hopeful revolution turned into belligerence, then into strife followed by a war, as if a new regional order was endorsed to guarantee instability and chaos in the region.

This new regional order has markedly new features and novel actors. The feature most starkly apparent is the rise of non-state actors, which have bolstered their presence and influence across the region, disregarding borders and ignoring the strategic equations that ruled the region for decades.Non-state actors, mainly Islamic movements like Hamas, Hezbollah and Al-Qaeda, played a limited role in the pre-Arab Spring era.

However, before looking at the new non-state actors and their role in the region, it is worth highlighting a number of facts concerning Islamic movements. Firstly, any designations that labelled those movements, like political Islam or moderate Islam, are merely descriptive terms and have nothing to do with the core of Islam as a religion.

Islam is a comprehensive and inclusive religion and attaching one characteristic, without a reference to others, may give the false impression that there are different forms of Islam, such as “non-moderate” Islam. One may argue, though, that such labels are simply “creative” terms to differentiate between the various Islamic groups.

For instance, several Western powers found in “moderate Islam” an acceptable term that may justify “dealing” with specific groups and not others; the limits of the word “dealing” can range from basic and regular contacts to alliances and common interests and agendas.

On the other hand, several Islamic groups did not shy away from being labelled as moderate Islam or political Islam as long as this distinguished them from other groups that took a violent path to achieve their goals. Being distinguished as “moderates” gives these groups some kind of legitimacy, and hence more freedom to work in their societies to achieve their goals.

Perhaps designating these groups as “movements with Islamic orientation” would be a more accurate approach, as they tend to share one goal: the return of Islamic rule, either state or through Islamic law, the shariah; the only difference is the time factor which implies their behaviour and reveals their strategy.

If a group seeks to achieve its goals gradually, its behavior and activities are characterised principally by peaceful means. Conversely, if the group seeks instant change, its policies and actions tend to be characterised by radical and violent means. Returning to the role of non-state actors in general, one should concede that with the advent of the Arab revolts, their role has become more evident to a degree that it has surpassed the role of many regimes and governments in the region.

These actors began to impose certain policies and agendas on regional and global regimes and are at the helm of every regional summit and international conference. The emergence of these actors has turned the whole region on its head, broken many taboos and penetrated one country after another. Puritanism is now widespread across the Middle East and new vocabulary – such as apostates, infidels and heretics – has become common in daily conversations.

In no time, these actors could abolish traditional political borders drawn in the early years of the last century (by the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement) when other ideas, concepts or phenomenon, like globalisation, took decades to find their way into the region. They and their offshoots spread throughout the region, taking various names: Al-Qaeda, Al-Nusra Front, Daesh or ISIS or IS, the Houthis and so on.

Their expansion does not appear to have any limits or borders. That being said, they have been seen to possess sophisticated organisation that does not reflect the limited number of their members and recruits. In other words, the number of their members can’t, by any means, reflect the unprecedented “achievements” they have attained in such a short time.

The most important element in this novel equation is their network of known and unknown allies who provide them with finance, logistics and arms, mainly away from the spotlight. The situations in Iraq and Syria represent the starkest example of entangled interests and relations from one side, and regional and international hesitation from the other.

Some regional powers opted to keep the card of “supporting or turning a blind eye to the activities and movements of those non-state actors” as a last gamble, lest things veer out of control on other fronts and so as to weaken groups like Hezbollah or the PKK, or even to harm the Assad regime. Similarly, many Western powers, who classify Hezbollah as a terrorist organisation, ignored its outright intervention in Syria in order to weaken all those groups (the “bad guys”) in a destructive conflict that took on a sectarian hue.

The US was able to pounce on this opportunity and use it to re-promote to its Arab allies the importance of its role as a supplier of weapons, as an adviser who provides them with information and expertise in fighting terrorism, and as a protector through US-led coalition strikes.

The reports which showed the evolution in American weapons sales, mainly to Arab countries, are just a case in point. Russia, which is fully aware that a nuclear deal with Iran would definitely harm its economy (any agreement with Tehran would lead to the return of Iran as a major oil supplier which will eventually lead to a drop in oil prices), had no choice but to bless this deal knowing the importance of Iran’s regional network of relations, mainly with non-state actors.

Intriguingly, and despite regional dismay at the existence of non-state actors and their rejection of any talks about a new Sykes-Picot deal, one may realise that facts on the ground are going nowhere but to that end. Since America launched its campaign against ISIS, the latter has taken control of a large swathe of Iraq and Syria, whereas before the strikes it controlled relatively small areas.

ISIS’s fighters began to appear more equipped and trained and their media performance has improved a great deal. The consecutive successes of ISIS have encouraged others either to follow suit or to attach themselves to this “successful” model; as a result, not one single Arab capital has become immune, especially in the aftermath of the so-called Arab Spring.

Although many analyses questioned the conditions that brought forth most of those actors and their real goals, and despite the fact that many investigations have shown suspicious features in the activities of those groups, the region appears to be slipping inadvertently towards malignant ends.

In an attempt to evaluate the aftermaths of the existence and acts of the rising non-state actors, one may say that distorting the image of Islam was unambiguous. Secondly, some of these actors, who used to enjoy popularity among the Arab masses for resisting Israel, appear to have lost ground in the Arab streets as they were tainted by either violence or sectarian agendas. Thirdly, Israel, which was isolated in the region for decades, was uniquely endowed and could enter the regional dynamics through the door of such actors.

To elaborate, Israel remained unscathed on the fringes of the Arab Spring and its repercussions, and won triple-level strategic gains from the emergence of the non-state actors. For a start, the government in Tel Aviv started to sow a network of relations with many Arab regimes that share, in theory at least, common fears, especially a potential Shia menace as represented by Iran and Hezbollah. Israel has also gained by the weakening of traditional Arab states, such as Iraq and Syria, which were a threat to Israeli decision makers.

Furthermore, it benefits Israel when world attention is distracted from what is still the core issue in the Middle East, its ongoing colonial occupation of Palestine. In sum, it appears that the region is in desperate need of a real leader, a new Saladin, who can put an end to the misery, the divisions and the schisms that afflict the Middle East; someone who is able to find a solution for the absence of a religious reference which has resulted in a chaotic and austere interpretation of Islam.

Comments Off on The Arab Spring and the Rise of non-State Actors

The Arab Spring and the Rise of non- State Actors

June 13th, 2015

By Fadi El-Husseini.

In the past four years, Arabs have been living in an endless Sisyphean ordeal, an unexpected nightmare after rising for what they called “the Arab Spring”. The scenario was cloned in most Arab Spring countries. Alas, hopeful revolution turned into belligerence, then into strife followed by a war, as if a new regional order was endorsed to guarantee instability and chaos in the region. This new regional order has markedly new features and novel actors. The feature most starkly apparent is the rise of non-state actors, which have bolstered their presence and influence across the region, disregarding borders and ignoring the strategic equations that ruled the region for decades.

Non-state actors, mainly Islamic movements like Hamas, Hezbollah and Al-Qaeda, played a limited role in the pre-Arab Spring era. However, before looking at the new non-state actors and their role in the region, it is worth highlighting a number of facts concerning Islamic movements.

Firstly, any designations that labelled those movements, like political Islam or moderate Islam, are merely descriptive terms and have nothing to do with the core of Islam as a religion. Islam is a comprehensive and inclusive religion and attaching one characteristic, without a reference to others, may give the false impression that there are different forms of Islam, such as “non-moderate” Islam. One may argue, though, that such labels are simply “creative” terms to differentiate between the various Islamic groups.

For instance, several Western powers found in “moderate Islam” an acceptable term that may justify “dealing” with specific groups and not others; the limits of the word “dealing” can range from basic and regular contacts to alliances and common interests and agendas. On the other hand, several Islamic groups did not shy away from being labelled as moderate Islam or political Islam as long as this distinguished them from other groups that took a violent path to achieve their goals. Being distinguished as “moderates” gives these groups some kind of legitimacy, and hence more freedom to work in their societies to achieve their goals.

Perhaps designating these groups as “movements with Islamic orientation” would be a more accurate approach, as they tend to share one goal: the return of Islamic rule, either state or through Islamic law, the shari’ah; the only difference is the time factor which implies their behaviour and reveals their strategy. If a group seeks to achieve its goals gradually, its behaviour and activities are characterised principally by peaceful means. Conversely, if the group seeks instant change, its policies and actions tend to be characterised by radical and violent means.

Returning to the role of non-state actors in general, one should concede that with the advent of the Arab revolts, their role has become more evident to a degree that it has surpassed the role of many regimes and governments in the region. These actors began to impose certain policies and agendas on regional and global regimes and are at the helm of every regional summit and international conference.

The emergence of these actors has turned the whole region on its head, broken many taboos and penetrated one country after another. Puritanism is now widespread across the Middle East and new vocabulary – such as apostates, infidels and heretics – has become common in daily conversations. In no time, these actors could abolish traditional political borders drawn in the early years of the last century (by the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement) when other ideas, concepts or phenomenon, like globalisation, took decades to find their way into the region.

They and their offshoots spread throughout the region, taking various names: Al-Qaeda, Al-Nusra Front, Daesh or ISIS or IS, the Houthis and so on. Their expansion does not appear to have any limits or borders. That being said, they have been seen to possess sophisticated organisation that does not reflect the limited number of their members and recruits. In other words, the number of their members can’t, by any means, reflect the unprecedented “achievements” they have attained in such a short time. The most important element in this novel equation is their network of known and unknown allies who provide them with finance, logistics and arms, mainly away from the spotlight.

The situations in Iraq and Syria represent the starkest example of entangled interests and relations from one side, and regional and international hesitation from the other. Some regional powers opted to keep the card of “supporting or turning a blind eye to the activities and movements of those non-state actors” as a last gamble, lest things veer out of control on other fronts and so as to weaken groups like Hezbollah or the PKK, or even to harm the Assad regime. Similarly, many Western powers, who classify Hezbollah as a terrorist organisation, ignored its outright intervention in Syria in order to weaken all those groups (the “bad guys”) in a destructive conflict that took on a sectarian hue.

The US was able to pounce on this opportunity and use it to re-promote to its Arab allies the importance of its role as a supplier of weapons, as an adviser who provides them with information and expertise in fighting terrorism, and as a protector through US-led coalition strikes. The reports which showed the evolution in American weapons sales, mainly to Arab countries, are just a case in point.

Russia, which is fully aware that a nuclear deal with Iran would definitely harm its economy (any agreement with Tehran would lead to the return of Iran as a major oil supplier which will eventually lead to a drop in oil prices), had no choice but to bless this deal knowing the importance of Iran’s regional network of relations, mainly with non-state actors.

Intriguingly, and despite regional dismay at the existence of non-state actors and their rejection of any talks about a new Sykes-Picot deal, one may realise that facts on the ground are going nowhere but to that end. Since America launched its campaign against ISIS, the latter has taken control of a large swathe of Iraq and Syria, whereas before the strikes it controlled relatively small areas. ISIS’s fighters began to appear more equipped and trained and their media performance has improved a great deal. The consecutive successes of ISIS have encouraged others either to follow suit or to attach themselves to this “successful” model; as a result, not one single Arab capital has become immune, especially in the aftermath of the so-called Arab Spring.

Although many analyses questioned the conditions that brought forth most of those actors and their real goals, and despite the fact that many investigations have shown suspicious features in the activities of those groups, the region appears to be slipping inadvertently towards malignant ends.

In an attempt to evaluate the aftermaths of the existence and acts of the rising non-state actors, one may say that distorting the image of Islam was unambiguous. Secondly, some of these actors, who used to enjoy popularity among the Arab masses for resisting Israel, appear to have lost ground in the Arab streets as they were tainted by either violence or sectarian agendas. Thirdly, Israel, which was isolated in the region for decades, was uniquely endowed and could enter the regional dynamics through the door of such actors. To elaborate, Israel remained unscathed on the fringes of the Arab Spring and its repercussions, and won triple-level strategic gains from the emergence of the non-state actors.

For a start, the government in Tel Aviv started to sow a network of relations with many Arab regimes that share, in theory at least, common fears, especially a potential Shia menace as represented by Iran and Hezbollah. Israel has also gained by the weakening of traditional Arab states, such as Iraq and Syria, which were a threat to Israeli decision makers. Furthermore, it benefits Israel when world attention is distracted from what is still the core issue in the Middle East, its ongoing colonial occupation of Palestine.

In sum, it appears that the region is in desperate need of a real leader, a new Saladin, who can put an end to the misery, the divisions and the schisms that afflict the Middle East; someone who is able to find a solution for the absence of a religious reference which has resulted in a chaotic and austere interpretation of Islam.

Comments Off on The Arab Spring and the Rise of non- State Actors

The Charlie effect: What’s next?

March 4th, 2015

By Fadi El Husseini.

Are we witnessing a harbinger of a religious war? Is it the beginning of a new violent era that may not spare any nation? What is that radicalism wants to achieve by committing such acts? Why is this happening? And is there a solution? These are few questions that appear in the daily debates and articles in the aftermath of the Paris events. It is crucial to investigate the backgrounds of this state of affairs, particularly from a Middle Eastern and Muslim perspective, in order to provide sound analysis and practical prognosis. Read the rest of this entry “

Comments Off on The Charlie effect: What’s next?

Is there peace partners in Israel?

December 19th, 2014

By Fadi Husseini.

Again, the peace process between the Palestinians and the Israelis has been grinded into halt and each party blames the other for this unfortunate failure. Israeli officials repeat continuously that there is no Palestinian peace partner and accuse Abbas and his authority of flexing their diplomatic muscles in an attempt to isolate Israel internationally and making unilateral steps; i.e. avoiding negotiations and seeking individual and/or collective recognition of the state of Palestine. However, it would be outlandish to imagine that the Palestinians would succeed in this approach (if it is true) without a minimum international understanding of the Palestinian narrative. In order to fully comprehend this state of affairs, it is crucial to make an assessment of the positions and announcements of each party.

Since he began his tenure as president of the Palestinian Authority in 2005, Mahmoud Abbas renounced violence and announced repeatedly his vision: a peaceful resolution of the conflict that would eventually lead to a Palestinian independent state. His vision complies perfectly with widely accepted and supported two-state solution based on relevant international and UN resolutions.

The path Abbas opted to take was not an easy one especially that it came in the aftermath of the second Intifada with massive amount of causalities and damage in the Palestinian infrastructure, society and lives. Notwithstanding the Palestinian domestic conditions were not ready for such approach, Abbas stated it clearly and irked many of his companions and political rivals as well.

Abbas said “We don’t want to use force. We don’t want to use weapons. We want to use diplomacy. We want to use politics. We want to use negotiations. We want to use peaceful resistance. That’s it.”[1] Better still, Abbas dared to criticize home-made rockets launched from the Gaza Strip. His criticism was neither to please Israel nor to satisfy Americans, but rather came out of his deep conscious and belief in a peaceful resolution of this conflict.

As part of the Palestinian commitments toward peace, and despite criticism, Abbas dismantled all Palestinian armed groups in the West Bank and united the Palestinian Security Forces (mainly policing service and not a regular army) under his direct command. Hitherto, not even one single violation was recorded from those forces. Rather and whilst many Israeli settlers carried out attacks on Palestinian private proprieties and lives, the Palestinian forces handed over many settlers to the Israeli authorities unharmed, when they lost their way in the Palestinian territories, putting Abbas and his forces under criticism from his political rivals.

Arafat, Abbas and the Palestinian leadership announced their acceptance of the two-state solution and the recognition of the State of Israel. Abbas last announcement came on November 24 calling on the international community to compel Israel to comply with its legal obligations regarding international resolutions, saying he is ready to set up a Palestinian state on only 22 per cent of historical Palestine. That said, half of the population who live on historical Palestine would live in the state of Israel on 78 per cent of the land and the other half of the population would live in the state of Palestine in only 22 per cent.

Peace talks between the Palestinians and the Israelis have been on since 1991, during which period Israeli settlement activities quadrupled on the Palestinian occupied land. Considering this fact, the Palestinians have requested to set up a time frame for negotiations which can’t last forever while watching Israel running afoot in changing facts on the ground and witnessing their land being chewed up day after day. Hence, as a result of Israeli refusal neither to accept the time frame nor to halt its settlement activities, weary Palestinians started to seek justice through international forums and agencies; mainly the UN.

On the other hand, although Israel accepted two-state solution and signed the Oslo Accords in 1993, none of the consecutive Israeli governments has, thus far, recognized the state of Palestine. Israel recognized the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) as a representative of the Palestinian people and still refuses to recognize the state of Palestine.

Many Israeli officials have openly expressed their rejection of the establishment of the Palestinian state and the current campaign for the general elections in Israel manifested this approach when the various parties running for elections (e.g. Likud, Jewish Home “HaBayit HaYehudi”…etc)announced their opposition of any future Palestinian state. Netanyahu have never missed any opportunity to state Israel’s inherent right to the whole biblical land of Israel, undermining any prospects of the establishment of a Palestinian state at least in the minds of his audience.