By Joseph Colomer.

Some people wonder whether the Greek government of Syriza headed by Alex Tsipras is a group of maverick politicians and skilful game theorists or a bunch of amateurs who improvise every move and don’t know where to go next. A clue to bend on the latter interpretation is how they have called this Sunday’s referendum. It’s not only that it has been called only one week in advance, that the question is undecipherable, and that they may not get on time to cover all the towns and islands of the country. It’s that the question is upside down!

An elementary rule for callers of a referendum is to call ‘yes’ to what the callers want. This is due, first of all, to a basic democratic element of accountability. A referendum is to ratify (or reject) some proposal or decision previously made by the government, the parliament or whoever organizes the query. If the government’s proposal is rejected, which rarely happens, then the government must resign and its proposal will not be implemented. See how this was the case in Ireland a few weeks ago, where the government called for ‘yes’ to same-sex marriage and won. In last year’s referendum for independence of Scotland, the Scottish government also called for a yes, and as it lost, it resigned. Even in the a-legal query in Catalonia about a similar issue a few months ago, the Catalan government asked for a ‘yes-yes’ (which won but was not validated due to low turnout).

The only occasions on which the government can call ‘no’ is when the referendum is promoted by a group of citizens to challenge some existing legislation, which may happen in a few places like Alaska or Utah, for instance. In fact, most popular initiatives against government-backed legislation loss. And no sound government takes the initiative to call a referendum to vote ‘no’.

The other ‘strategic’ reason to call for ‘yes’ is psychological. In general, people prefer ‘yes’: it’s positive, optimistic, it may be based on trust, it comes first to your mind, it’s easy to deliver. ‘No’, in contrast, may require more information on the intricate matter and an attitude of distrust and angriness. Campaigning for a ‘yes’ vote is certainly easier and more cheerful than a ‘no’. Aware of this, the Britons are discussing the question for the announced referendum about Brexit from the EU (which is not going to be called one week before, like the Greek one, but about two years in advance). The independent British Electoral Commission suggested that in addition to the obvious question: “Should the UK remain a member of the EU? Yes or No”, the government should consider a less biased question with the “neutral wording”: “Should the UK remain a member of the EU or leave the EU? Remain or Leave”. Still, the status-quo (remain) would be favored. But surely the British government will feel emboldened to have its own way.

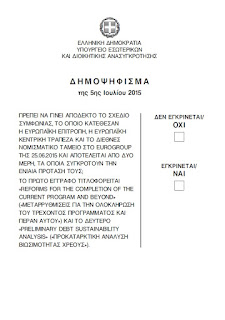

The Greek callers are trying the silly trick of putting ‘No’ above ‘Yes’ in the unreadable and bilingual ballot, as can be seen in the image (Oxi=No, Nay=Yes). This may mislead some voters to vote for the first available option, but it can also surprise others that can react against a too obvious suggestion.

This Sunday in Greece, if ‘no’ wins, the EU loses. But the Tsipras government would not win anything. Syriza called ‘no’ precisely because they have no-thing to offer. If the ‘yes’ wins, the governments loses and the EU wins. Then it’s the EU that should manage the victory and rule in Greece.