By Syed Qamar Rizvi.

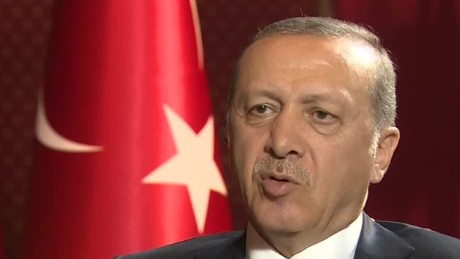

Much is being discussed in the Western print media about Turkey’s President Tayyab Erdogan’s foreign policy ventures. But it appears that what Erdogan is doing, he is trying his best to defend his country’s strategic interests. However, a look– into the following discussed foreign policy reflections—provides much food for thought.

On two separate occasions, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan criticized the Treaty of Lausanne, which created the borders of modern Turkey, for leaving the country too small. He spoke of the country’s interest in the fate of Turkish minorities living beyond these borders, as well as its historic claims to the Iraqi city of Mosul, near which Turkey has a small military base. And, alongside news of Turkish jets bombing Kurdish forces in Syria and engaging in mock dogfights with Greek planes over the Aegean Sea, Turkey’s pro-government media have shown a newfound interest in a series of imprecise, even crudely drawn, maps of Turkey with new and improved borders.

Turkey won’t be annexing part of Iraq anytime soon, but this combination of irredentist cartography and rhetoric nonetheless offers some insight into Turkey’s current foreign and domestic policies and Ankara’s self-image. The maps, in particular, reveal the continued relevance of Turkish nationalism, a long-standing element of the country’s statecraft, now reinvigorated with some revised history and an added dose of religion. But if the past is any indication, the military interventions and confrontational rhetoric this nationalism inspires may worsen Turkey’s security and regional standing. Erdogan, by contrast, has given voice to an alternative narrative in which Ataturk’s willingness in the Treaty of Lausanne to abandon territories such as Mosul and the now-Greek islands in the Aegean was not an act of eminent pragmatism but rather a betrayal. The suggestion, against all evidence, is that better statesmen, or perhaps a more patriotic one, could have gotten more.

Mr. Erdogan, the country’s leader for 14 years, is the one chiefly responsible for putting the Ottoman Empire at the center of Turkey’s collective imagination. The Ottoman sultans are often hailed as the caliphs of the Muslim world. This is not lost on the supporters of Mr. Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party – the A.K.P. The chairman of the A.K.P’s youth wing recently declared Mr. Erdogan “president of all the world’s Muslims.” A Muslim Brotherhoodcleric echoed similar sentiments when he declared, Turkey’s president as “the hope of all Muslims and of Islam”.

These ambitions seem to have had a distinct effect on Turkey’s Middle East policy. After Syria’s civil war began in 2011, Ankara sought to topple Assad’s regime by bringing in Islamist allies. For this purpose, it funded loyal armed groups to do its bidding- groups named after Ottoman rulers -the Sultan Murad Brigade being one example. Nonetheless, recently Erdogan has displayed political maturity by being an integral part of the recent Moscow Declaration with Russia and Iran- the joint eight-point statement of principles calls for the extension of a ceasefire throughout Syria and a negotiated settlement between the Syrian government and its opponents.

In August, the Syrian Kurds, with American support, were poised to gain control of a long strip along the Turkish-Syrian border. Once this became clear, Turkey, together with its Syrian proxies, launched a military operation to push back the Kurds and the Islamic State.

It was a success — of sorts. Turkey and its proxies gained control of an area that they used to create a buffer zone between two Syrian Kurdish-administered territories. Iran and Russia, too, were happy to see the American-backed group’s ambitions checked. If Syria’s Kurds were to achieve independence with American assistance, Moscow and Tehran feared, they could be counted on to remain an American ally and perhaps even to host American military bases, threatening Iranian and Russian interests. Accordingly, by using Turkey to beat the Syrian Kurds, Moscow and Tehran hope to drive them away from the United States and into their own arms.

Turkey’s rapprochement with Russia goes beyond Syria. Lately, Mr. Erdogan has been openly toying with the idea of joining the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a pact led by Russia and China that is meant to rival the European Union. In doing so, Turkey is turning away from potential partners in the West that still — at least for now — value democracy and human rights, and toward another world of autocrats, pseudo-monarchs and aspiring czars.

“Due to the active action of Turkey and Russia we managed to bring the rival forces together, and due to our joint effort the Syrian ceasefire continues,” Putin told reporters on Friday, hailing Ankara’s “exceptional cooperation” in keeping the truce.

For his part, Erdogan said that there are “no doubts” about the “very successful” Syria talks sponsored by the two countries, adding that Turkey was cooperating entirely with Russia’s military. Erdogan also praised the two countries’ friendship, saying it is “strong enough to overcome their differences”, even as he urged Russia to lift all sanctions it imposed on Ankara following the downing of a Russian plane in 2015.

The increasingly close cooperation on Syria between Russia and Turkey marks a sharp turnaround for the two nations, which have also coordinated their operations against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) armed group in Syria.

Russia has an active military presence in Syria in support of Assad’s forces, while Turkey, which backs anti-Assad groups, launched a military operation in August to create a safe zone along its border inside Syria. Tensions between the German and Turkish governments, triggered by the arrest of Die Welt’s correspondent Deniz Yücel and culminating in Erdoğan accusing Germany of “Nazi practices” over banned rallies in German cities, had merely strengthened his allegiance, said 20-year-old Mehmet. “To be honest, when America, Germany and France tell me to vote no in the referendum, then I am going to vote yes.”

Both said no German party represented their interests: “We are just foreigners to them.”

The heightened fervour of support for Erdoğan even among younger members of Germany’s population with Turkish roots – a community of about 3 million, of which roughly half are entitled to vote in April – has scandalised the country’s public and media.

German politicians allege that the AKP is trying to influence the diaspora vote not just through public rallies but by covertly pressurising and threatening its opponents in Germany via religious and business networks. In January, Turkish-German footballer Hakan Çalhanoğlu was publicly criticised by his club Bayer Leverkusen for posting a video on social media in which he declared his allegiance with the evet (yes) camp.

Nevertheless, being highly frustrated over the European Union’s exclusive behavior regarding Turkey’s EU’s bid; and being dejected from German ‘s orthodox foreign policy behavior, and being extremely dismayed over US’s backing of the Kurds in Syria and Iraq, President Erdogan has been trying to reorient Turkey’s foreign policy keeping in view the current geostrategic and geopolitical dimensions of the region. His tilt towards both Russia and Iraq seems to warrant the fact that he wants to protect Turkey’s interests both regionally and globally.