By TDJ data awareness recollection gathering.

From WIkiPedia.

Verified for content accuracy by The Daily Journalist

MAINWAY is a database maintained by the United States’ National Security Agency (NSA) containing metadata for hundreds of billions of telephone calls made through the four largest telephone carriers in the United States: At&t, SBC, BellSouth (all three now called AT&T), and Verizon.

The existence of this database and the NSA program that compiled it was unknown to the general public until USA Today broke the story on May 10, 2006. It is estimated that the database contains over 1.9 trillion call-detail records. According to Bloomberg News, the effort began approximately seven months before the September 11, 2001 attacks. As of June 2013, the database stores metadata for at least five years.

The records include detailed call information (caller, receiver, date/time of call, length of call, etc.) for use in traffic analysis and social network analysis, but do not include audio information or transcripts of the content of the phone calls.

The database’s existence has prompted fierce objections. It is often viewed as an illegal warrantless search and a violation of the pen register provisions of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act and (in some cases) the Fourth Amendment of the United States Constitution.

By University of Pennsylvania.

The program, known by its unclassified nickname “Stellar Wind,” is code named

“RAGTIME.”

1. Who has access?

Only about 3 dozen NSA officials have access to the intercept data from

RAGTIME’s domestic counter-terrorism collection operation.

Source: turn.com

2. Who contributes to the program?

As many as 50 companies have provided data to the program

3. How does it collect data?

In order to collect on a target, the NSA needs one additional piece of evidence

besides its own proprietary link-analysis protocols which assigns probability scores

to each potential target.

Source: i-logue.com

4. How does it interact with NSA?

Although the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court rarely rejects RAGTIME-P

requests, it often asks the NSA to provide more information before it approves

them.

Source: en.wikipedia.org

5. What is program XKEYSCORE?

At Fort Meade, a program called XKEYSCORE processes all signals before they are

shunted off to various “production lines” that deal with specific issues. PINWALE is

the main NSA database for recorded signals intercepts. It is compartmentalized by

keywords (the NSA calls them “selectors”). Metadata is stored in a database called

MARINA and is generally retained for five years.

Source: williamaarkin.wordpress.com

6. How do they access reporting?

“Finished reporting,” or transcripts and analysis of calls, is accessed through the

MAUI database. (Metadata is never included in MAUI.) There are dozens of other

NSA signals activity lines, or SIGADS, that process data in parallel. Among the

active databases and systems: ANCHORY, an all-source database for

communications intelligence; HOMEBASE, which allows analysts to coordinate their

searches with DNI mission priorities; AIRGAP, which deals with priority DOD

missions; WRANGLER, which focuses on electronic intelligence; TINMAN, a

database related to air warning and surveillance; OILSTOCK, a system for analyzing

air warning and surveillance data; and many more.[i]

7. How does the FBI interact with the program?

The Bush Administration believed that the program was highly protected, and

instructed the NSA to share only the most essential data with the FBI. But the FBI

had “read in” more than 500 of its special agents. Had policy-makers been aware

of this, sharing the RAGTIME data and its sources would have been much more

efficient and would have allowed the FBI to separate the wheat from the chaff must

more easily.

Image by Julie Jacobson / AP

8. What happened with the New York Times?10,757 Views

NSA Director Michael Hayden was secretly pleased that the New York Times

withheld significant details of the program when the articles revealing it were first

published, but he play-acted in public, castigating the Times for their indiscretion.

9. How does NSA know if something is wrong with

the attorney general?

The set-up to the famous hospital-room confrontation between White House

counsel Alberto Gonzales and ailing Attorney General John Ashcroft : James

Comey, as acting attorney general, refused to affix his signature to a specific set of

certifications provided by the Justice Department to Internet, financial and data

companies, believing that the justification for providing the bulk data to the NSA

was not sufficient. The White House panicked, because they worried that the

companies would simply stop cooperating with the NSA if they suddenly didn’t see

the signature of attorney general. They would know that something was wrong.

Source: guardian.co.uk

10. What does Congress think about surveillance

laws?

Congress repeatedly resisted the entreaties of the Bush Administration to change

the surveillance laws once the RAGTIME program had been institutionalized. This

was for a simple reason: they did not want to be responsible for a program that was

not legal

By Empty Wheel. Net,

CNET is getting a lot of attention for its report that NSA, “has acknowledged in a new classified briefing that it does not need court authorization to listen to domestic phone calls.”

In general, I’m just going to outsource my analysis of what the exchange means to Julian Sanchez (I hope he doesn’t charge me as much as Mike McConnell’s Booz Allen Hamilton for outsourced analysis).

What seems more likely is that Nadler is saying analysts sifting through metadata have the discretion to determine (on the basis of what they’re seeing in the metadata) that a particular phone number or e-mail account satisfies the conditions of one of the broad authorizations for electronic surveillance under §702 of the FISA Amendments Act.

[snip]

The analyst must believe that one end of the communication is outside the United States, and flag that account or phone line for collection. Note that even if the real target is the domestic phone number, an analyst working from the metadatabase wouldn’t have a name, just a number. That means there’s no “particular, known US person,” which ensures that the §702 ban on “reverse targeting” is, pretty much by definition, not violated.

None of that would be too surprising in principle: That’s the whole point of §702!

That is, what Nadler may have learned that the same analysts who have access to the phone metadata may also have authority to issue directives to companies for phone content collection. If so, it would be entirely feasible for the same analyst to learn, via the metadata database, that a suspect phone number is in contact with the US and for her to submit a request for actual content to the providers, without having to first get a FISA order covering the US person callers directly. Since she was still “targeting” the original overseas phone number, she would be able to get the US person content without a specific order.

I just want to point to a part of this exchange that everyone is ignoring (but that I pointed out while live tweeting this).

Mueller: I’m not certain it’s the same–I’m not certain it’s an answer to the same question.

Mueller didn’t deny the NSA can get access to US person phone content without a warrant. He just suggested that Nadler might be conflating two different programs or questions.

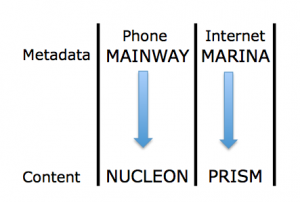

And that’s one of the things to remember about this discussion. Among many other methods of shielding parts of the programs, the government is thus far discussing primarily the two programs identified by the Guardian: the phone metadata collection (which the WaPo reports is called MAINWAY) and the Internet content access (PRISM).

Thus, we are effectively just talking about two programs, and not two that intersect via targeted technology, as MAINWAY would with NUCLEON and MARINA with PRISM. So, while there are a slew of other possibilities for what Mueller might mean by “another question,” one big one is “how may an analyst access NUCLEON information if she had MAINWAY data”?

And, as Sanchez notes in his piece, the way 702 is supposed to work (and indeed, would have to work for the claims made about PRISM’s role in thwarting the Najibullah Zazi attack to be remotely true) is that US person information comes up along with targeted foreign targets. Indeed, as I noted last year during the FISA Amendments Act debate, in an effort to defeat this amendment prohibiting effectively what Sanchez has laid out, Sheldon Whitehouse said that getting US content without a warrant was the entire point.

He referred back to his time using warrants as a US Attorney, and said that requiring a warrant to access the US person communication would “kill this program,” and that to think warrants “fundamentally misapprehends the way in which this program operates.”

The possibility that the government would do this kind of thing has been raised repeatedly since Russ Feingold did so in 2009 during the FISA Amendments Act debates, speaking specifically about the content of calls to people overseas.

It may be that, discussed in isolation, the government can avoid talking about what Feingold and Wyden and others have called a backdoor. Which is probably why they don’t want us to “confuse” (that is, understand the relationship between) the business records and content access.

By James Ball.

The National Security Agency is storing the online metadata of millions ofinternet users for up to a year, regardless of whether or not they are persons of interest to the agency, top secret documents reveal.

Metadata provides a record of almost anything a user does online, from browsing history – such as map searches and websites visited – to account details, email activity, and even some account passwords. This can be used to build a detailed picture of an individual’s life.

The Obama administration has repeatedly stated that the NSA keeps only the content of messages and communications of people it is intentionally targeting – but internal documents reveal the agency retains vast amounts of metadata.

An introductory guide to digital network intelligence for NSA field agents, included in documents disclosed by former contractor Edward Snowden, describes the agency’s metadata repository, codenamed Marina. Any computer metadata picked up by NSA collection systems is routed to the Marina database, the guide explains. Phone metadata is sent to a separate system.

“The Marina metadata application tracks a user’s browser experience, gathers contact information/content and develops summaries of target,” the analysts’ guide explains. “This tool offers the ability to export the data in a variety of formats, as well as create various charts to assist in pattern-of-life development.”

The guide goes on to explain Marina’s unique capability: “Of the more distinguishing features, Marina has the ability to look back on the last 365 days’ worth of DNI metadata seen by the Sigint collection system,regardless whether or not it was tasked for collection.” [Emphasis in original.]

On Saturday, the New York Times reported that the NSA was using itsmetadata troves to build profiles of US citizens’ social connections, associations and in some cases location, augmenting the material the agency collects with additional information bought in from the commercial sector, which is is not subject to the same legal restrictions as other data.

The ability to look back on a full year’s history for any individual whose data was collected – either deliberately or incidentally – offers the NSAthe potential to find information on people who have later become targets. But it relies on storing the personal data of large numbers of internet users who are not, and never will be, of interest to the US intelligence community.

Marina aggregates NSA metadata from an array of sources, some targeted, others on a large scale. Programs such as Prism – which operates through legally compelled “partnerships” with major internet companies – allow the NSA to obtain content and metadata on thousands of targets without individual warrants.

The NSA also collects enormous quantities of metadata from the fibre-optic cables that make up the backbone of the internet. The agency has placed taps on undersea cables, and is given access to internet data through partnerships with American telecoms companies.

About 90% of the world’s online communications cross the US, giving theNSA what it calls in classified documents a “home-field advantage” when it comes to intercepting information.

By confirming that all metadata “seen” by NSA collection systems is stored, the Marina document suggests such collections are not merely used to filter target information, but also to store data at scale.

A sign of how much information could be contained within the repository comes from a document voluntarily disclosed by the NSA in August, in the wake of the first tranche of revelations from the Snowden documents.

The seven-page document, titled “The National Security Agency: Missions, Authorities, Oversight and Partnerships”, says the agency “touches” 1.6% of daily internet traffic – an estimate which is not believed to include large-scale internet taps operated by GCHQ, the NSA’s UK counterpart.

The document cites figures from a major tech provider that the internet carries 1,826 petabytes of information per day. One petabyte, according to tech website Gizmodo, is equivalent to over 13 years of HDTV video.

“In its foreign intelligence mission, NSA touches about 1.6% of that,” the document states. “However, of the 1.6% of the data, only 0.025% is actually selected for review.

“The net effect is that NSA analysts look at 0.00004% of the world’s traffic in conducting their mission – that’s less than one part in a million.”

However, critics were skeptical of the reassurances, because large quantities of internet data is represented by music and video sharing, or large file transfers – content which is easy to identify and dismiss without entering it into systems. Therefore, the NSA could be picking up a much larger percentage of internet traffic that contains communications and browsing activity.

Journalism professor and internet commentator Jeff Jarvis noted: “[By] very rough, beer-soaked-napkin numbers, the NSA’s 1.6% of net traffic would be half of the communication on the net. That’s one helluva lot of ‘touching’.”

Much of the NSA’s data collection is carried out under section 702 of theFisa Amendments Act. This provision allows for the collection of data without individual warrants of communications, where at least one end of the conversation, or data exchange, involves a non-American located outside the US at the time of collection.

The NSA is required to “minimize” the data of US persons, but is permitted to keep US communications where it is not technically possible to remove them, and also to keep and use any “inadvertently” obtained US communications if they contain intelligence material, evidence of a crime, or if they are encrypted.

The Guardian has also revealed the existence of a so-called “backdoor search loophole”, a 2011 rule change that allows NSA analysts to search for the names of US citizens, under certain circumstances, in mass-data repositories collected under section 702.

According to the New York Times, NSA analysts were told that metadatacould be used “without regard to the nationality or location of the communicants”, and that Americans’ social contacts could be traced by the agency, providing there was some foreign intelligence justification for doing so.

The Guardian approached the NSA with four specific questions about the use of metadata, including a request for the rationale behind storing 365 days’ worth of untargeted data, and an estimate of the quantity of US citizens’ metadata stored in its repositories.

But the NSA did not address any of these questions in its response, providing instead a statement focusing on its foreign intelligence activities.

“NSA is a foreign intelligence agency,” the statement said. “NSA’s foreign intelligence activities are conducted pursuant to procedures approved by the US attorney general and the secretary of defense, and, where applicable, the foreign intelligence surveillance (Fisa) court, to protect the privacy interests of Americans.

“These interests must be addressed in the collection, retention, and dissemination of any information. Moreover, all queries of lawfully collected data must be conducted for a foreign intelligence purpose.”

It continued: “We know there is a false perception out there that NSAlistens to the phone calls and reads the email of everyday Americans, aiming to unlawfully monitor or profile US citizens. It’s just not the case.

“NSA’s activities are directed against foreign intelligence targets in response to requirements from US leaders in order to protect the nation and its interests fro