By Alton Parrish.

Artificial lights raise night sky luminance, creating the most visible effect of light pollution—artificial skyglow. Despite the increasing interest among scientists in fields such as ecology, astronomy, health care, and land-use planning, light pollution lacks a current quantification of its magnitude on a global scale.

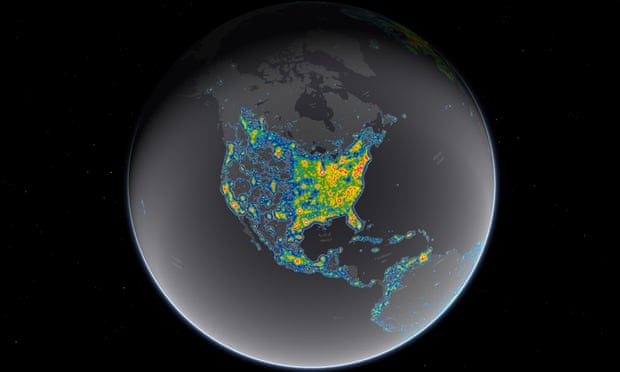

A new atlas of light pollution documents the degree to which the world is illuminated by artificial skyglow. In addition to being a scourge for astronomers, bright nights also affect nocturnal organisms and the ecosystems in which they live. The “New World Atlas of Artificial Night Sky Brightness” was published in the open access journal Science Advances on June 10, 2016.

The Milky Way disappears in Berlin’s light-dome.

Researchers from Italy, Germany, the USA, and Israel carried out the work, which was led by Fabio Falchi from the Italian Light Pollution Science and Technology Institute (ISTIL). “The new atlas provides a critical documentation of the state of the night environment as we stand on the cusp of a worldwide transition to LED technology” explains Falchi. “Unless careful consideration is given to LED color and lighting levels, this transition could unfortunately lead to a 2-3 fold increase in skyglow on clear nights.”

(1)

This atlas shows that more than 80% of the world and more than 99% of the U.S. and European populations live under light-polluted skies. The Milky Way is hidden from more than one-third of humanity, including 60% of Europeans and nearly 80% of North Americans. Moreover, 23% of the world’s land surfaces between 75°N and 60°S, 88% of Europe, and almost half of the United States experience light-polluted nights.

Major advances over a similar atlas from 2001 were possible thanks to a new satellite, and to the recent development of inexpensive sky radiance meters. City lighting information for the atlas came from the American Suomi NPP satellite, which includes the first instrument intentionally designed to make accurate observations of urban lights from space. The atlas was calibrated using data from “Sky Quality Meters” at 20,865 individual locations around the world. The participation of citizen scientists in collecting the calibration data was critical, according to Dr. Christopher Kyba, a study co-author, and researcher at the GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences. “Citizen scientists provided about 20% of the total data used for the calibration, and without them we would not have had calibration data from countries outside of Europe and North America.”

“The community of scientists who study the night have eagerly anticipated the release of this new Atlas” said Dr. Sibylle Schroer, who coordinates the EU funded “Loss of the Night Network and is not one of the study’s authors. The director of the International Dark-Sky Association, Scott Feierabend also hailed the work as a major breakthrough, saying “the new atlas acts as a benchmark, which will help to evaluate the success or failure of actions to reduce light pollution in urban and natural areas”.