Posts by AltonParrish:

Farming Started in Several Places at Once

July 5th, 2013

By Alton Parrish.

For decades archaeologists have been searching for the origins of agriculture. Their findings indicated that early plant domestication took place in the western and northern Fertile Crescent. In the July 5 edition of the journal Science, researchers from the University of Tübingen, the Tübingen Senckenberg Center for Human Evolution and Paleoenvironment, and the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research demonstrate that the foothills of the Zagros Mountains of Iran in the eastern Fertile Crescent also served as a key center for early domestication.

Archaeologists Nicholas Conard and Mohsen Zeidi from Tübingen led excavations at the aceramic tell site of Chogha Golan in 2009 and 2010. They documented an 8 meter thick sequence of exclusively aceramic Neolithic deposits dating from 11,700 to 9,800 years ago. These excavations produced a wealth of architectural remains, stone tools, depictions of humans and animals, bone tools, animal bones, and – perhaps most importantly – the richest deposits of charred plant remains ever recovered from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic of the Near East.

Simone Riehl, head of the archaeobotany laboratory in Tübingen, analyzed over 30,000 plant remains of 75 taxa from Chogha Golan, spanning a period of more than 2,000 years. Her results show that the origins of agriculture in the Near East can be attributed to multiple centers rather than a single core area and that the eastern Fertile Crescent played a key role in the process of domestication.

Many pre-pottery Neolithic sites preserve comparatively short sequences of occupation, making the long sequence form Chogha Golan particularly valuable for reconstructing the development of new patterns of human subsistence. The most numerous species from Chogha Golan are wild barley, goat-grass and lentil, which are all wild ancestors of modern crops. These and many other species are present in large numbers starting in the lowest deposits, horizon XI, dating to the end of the last Ice Age roughly 11,700 years ago. In horizon II dating to 9.800 years ago, domesticated emmer wheat appears.

The plant remains from Chogha Golan represent a unique, long-term record of cultivation of wild plant species in the eastern Fertile Crescent. Over a period of two millennia the economy of the site shifted toward the domesticated species that formed the economic basis for the rise of village life and subsequent civilizations in the Near East. Plants including multiple forms of wheat, barley and lentils together with domestic animals later accompanied farmers as they spread across western Eurasia, gradually replacing the indigenous hunter-gather societies. Many of the plants that were domesticated in the Fertile Crescent form the economic basis for the world population today.

Contacts and sources:

Universitaet Tübingen

Citation: Local emergence of agriculture in the foothills of the Zagros Mountains of Iran”, Science, July 5 2013, doi: 10.1126/science.1236743

Archaeological Excavations Reveal City Wall of Jerusalem from the Tenth Century B.C.E. – Possibly Built by King Solomon

July 1st, 2013

By Dr. Eilat Mazar.

Dr. Eilat Mazar, Hebrew University of Jerusalem archaeologist, points to the tenth century B.C.E. excavations that were uncovered under her direction in the Ophel area adjacent to the Old City of Jerusalem.

Credit: (Hebrew University photo by Sasson Tiram)

The section of the city wall revealed, 70 meters long and six meters high, is located in the area known as the Ophel, between the City of David and the southern wall of the Temple Mount.

Uncovered in the city wall complex are: an inner gatehouse for access into the royal quarter of the city, a royal structure adjacent to the gatehouse, and a corner tower that overlooks a substantial section of the adjacent Kidron valley.

The excavations in the Ophel area were carried out over a three-month period with funding provided by Daniel Mintz and Meredith Berkman, a New York couple interested in Biblical Archeology. The funding supports both completion of the archaeological excavations and processing and analysis of the finds as well as conservation work and preparation of the site for viewing by the public within the Ophel Archaeological Park and the national park around the walls of Jerusalem.

The excavations were carried out in cooperation with the Israel Antiquities Authority, the Israel Nature and Parks Authority, and the Company for the Development of East Jerusalem. Archaeology students from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem as well as volunteer students from the Herbert W. Armstrong College in Edmond, Oklahoma, and hired workers all participated in the excavation work.

“The city wall that has been uncovered testifies to a ruling presence. Its strength and form of construction indicate a high level of engineering”, Mazar said. The city wall is at the eastern end of the Ophel area in a high, strategic location atop the western slop of the Kidron valley.

“A comparison of this latest finding with city walls and gates from the period of the First Temple, as well as pottery found at the site, enable us to postulate with a great degree of assurance that the wall that has been revealed is that which was built by King Solomon in Jerusalem in the latter part of the tenth century B.C.E.,” said Mazar

“This is the first time that a structure from that time has been found that may correlate with written descriptions of Solomon’s building in Jerusalem,” she added. “The Bible tells us that Solomon built — with the assistance of the Phoenicians, who were outstanding builders — the Temple and his new palace and surrounded them with a city, most probably connected to the more ancient wall of the City of David.” Mazar specifically cites the third chapter of the First Books of Kings where it refers to “until he (Solomon) had made an end of building his own house, and the house of the Lord, and the wall of Jerusalem round about.”

The six-meter-high gatehouse of the uncovered city wall complex is built in a style typical of those from the period of the First Temple like Megiddo, Beersheva and Ashdod. It has symmetrical plan of four identical small rooms, two on each side of the main passageway. Also there was a large, adjacent tower, covering an area of 24 by 18 meters, which was intended to serve as a watchtower to protect entry to the city. The tower is located today under the nearby road and still needs to be excavated. Nineteenth century British surveyor Charles Warren, who conducted an underground survey in the area, first described the outline of the large tower in 1867 but without attributing it to the era of Solomon.

“Part of the city wall complex served as commercial space and part as security stations,” explained Mazar. Within the courtyard of the large tower there were widespread public activities, she said. It served as a public meeting ground, as a place for conducting commercial activities and cult activities, and as a location for economic and legal activities.

Pottery shards discovered within the fill of the lowest floor of the royal building near the gatehouse also testify to the dating of the complex to the 10th century B.C.E. Found on the floor were remnants of large storage jars, 1.15 meters in height, that survived destruction by fire and that were found in rooms that apparently served as storage areas on the ground floor of the building. On one of the jars there is a partial inscription in ancient Hebrew indicating it belonged to a high-level government official.

“The jars that were found are the largest ever found in Jerusalem,” said Mazar, adding that “the inscription that was found on one of them shows that it belonged to a government official, apparently the person responsible for overseeing the provision of baked goods to the royal court.”

In addition to the pottery shards, cult figurines were also found in the area, as were seal impressions on jar handles with the word “to the king,” testifying to their usage within the monarchy. Also found were seal impressions (bullae) with Hebrew names, also indicating the royal nature of the structure. Most of the tiny fragments uncovered came from intricate wet sifting done with the help of the salvaging Temple Mount Sifting Project, directed by Dr. Gabriel Barkai and Zachi Zweig, under the auspice of the Nature and Parks Authority and the Ir David Foundation.

Between the large tower at the city gate and the royal building the archaeologists uncovered a section of the corner tower that is eight meters in length and six meters high. The tower was built of carved stones of unusual beauty.

East of the royal building, another section of the city wall that extends for some 35 meters also was revealed. This section is five meters high, and is part of the wall that continues to the northeast and once enclosed the Ophel area.

Humanoid Robot That Sees And Maps

July 1st, 2013

Posted by Alton Parrish.

By using cameras, the robot builds a map reference relative to its surroundings and is able to “remember” where it has been before. The ability to build visual maps quickly and anywhere is essential for autonomous robot navigation, in particular when the robot gets into places that have no global positioning system (GPS) signals or other references.

Roboray is one of the most advanced humanoid robots in the world, with a height of 140 cm and a weight of 50 kg. It has a stereo camera on its head and 53 different actuators including six for each leg and 12 for each hand.

The robot features a range of novel technologies. In particular it walks in a more human-like manner by using what is known as dynamic walking. This means that the robot is falling at every step, using gravity to carry it forward without much energy use. This is the way humans walk and is in contrast to most other humanoid robots that “bend their knees to keep the centre of mass low and stable”. This way of walking is also more challenging for the computer vision algorithms as objects in images move more quickly.

The Bristol team, who have been collaborating with Samsung Electronics in South Korea since 2009, was in charge of the computer vision aspects of 3D SLAM (simultaneous localisation and mapping).

Dr Walterio Mayol-Cuevas, Deputy Director of the Bristol Robotics Lab, Reader in the Department of Computer Science at the University of Bristol and leader of the team, said: “A humanoid robot has an ideal shape to use the same tools and spaces designed for people, as well as a good test bed to develop machine intelligence designed for human interaction.

“Robots that close the gap with human behaviours, such as by featuring dynamic walking, will not only allow more energy efficiency but be better accepted by people as they move in a more natural manner.”

Dr Sukjune Yoon from the Samsung Advanced Institute of Technology (SAIT), speaking about the collaboration with the University of Bristol, said: “Bristol’s visual SLAM and their other real-time visual technologies have been very beneficial for Samsung Electronics’ humanoid robot project.

“Mapping in real-time for a biped humanoid is much harder than for wheeled vehicles not only because there is less constant contact with the ground. In the near future, it is expected that humanoid robotic technologies will be able to provide a valuable service to society with robots working alongside people.”

The technology of rapid 3D visual mapping, developed at Bristol, is internationally renowned because of its ability to robustly track and recover from rapid motions and occlusions, which is essential for when the humanoid moves and turns at normal walking speeds. This Bristol work has been used for a number of applications outside robotics too, from augmented reality to commercial applications in the analysis of wearable Gaze data.

A paper describing some aspects of this collaboration with Samsung is published in the journal Advanced Robotics.

Paper: Real-time 3D simultaneous localization and map-building for a dynamic walking humanoid robot, Yoon, Sukjune, Seungyong Hyung, Minhyung Lee, Kyung Shik Roh, SungHwan Ahn, Andrew Gee, Pished Bunnun, Andrew Calway, and Waterio W. Mayol-Cuevas, Advanced Robotics, published online ahead-of-print, Volume 27, Issue 10, 2013.

Dictionary Completed On Language Used Everyday In Ancient Egypt

June 28th, 2013

By Alton Parrish.

The ancient language is Demotic Egyptian, a name given by the Greeks to denote it was the tongue of the demos, or common people. It was written as a flowing script and was used in Egypt from about 500 B.C. to 500 A.D., when the land was occupied and usually dominated by foreigners, including Persians, Greeks and Romans.

The language lives on today in words such as adobe, which came from the Egyptian word for brick. The word moved through Demotic, on to Arabic and eventually to Spain during the time of Islamic domination there, explained Janet Johnson, editor of the Chicago Demotic Dictionary.

Ebony, the dark wood that was traded down the Nile from Nubia (present-day Sudan), also comes from Demotic roots. The name Susanis indirectly related to the Demotic word for water lily.

Photo by Jason Smith

“It was also used for religious and magical texts as well as scientific texts dealing with topics such as astronomy, mathematics and medicine. It is an indispensible tool for reconstructing the social, political and cultural life of ancient Egypt during a fascinating period of its history,” she continued.

“The University of Chicago is pretty much Demotic central,” said James Allen, PhD’81, the Wilbour Professor of Egyptology and chair of the Department of Egyptology and Ancient Western Asian Studies at Brown University. “Besides the Demotic dictionary, the University also has some of the world’s top experts on Demotic on its faculty.

Photo by Jason Smith

The Demotic language was one of the three texts on the Rosetta stone, which was also written in Egyptian hieroglyphs and Greek. In addition to being used on stone carvings, the script was left behind on papyrus and broken bits of pottery.

“Before Demotic, Egyptians developed a script form of hieroglyphs called hieratic; Demotic evolved from that. Because it was cursive, it was much easier and faster to use than were the elaborate pictures of the hieroglyphs,” said Johnson.

The script was particularly useful as a means of conducting everyday business, such as paying taxes. “People would write the information down on potsherds and put them in the basement, much as we keep track today of our income tax records by keeping copies of our past returns,” Johnson added.

Johnson, PhD’72, has worked with Demotic since she was a graduate student at the Oriental Institute. The advent of computer technology facilitated the assembly of the Demotic Dictionary, which unlike its older sister, the Chicago Assyrian Dictionary, could be organized electronically rather than on index cards.

The 21-volume Chicago Assyrian Dictionary was completed in 2011 after 90 years of work.

Credit; Jason Smith

The Assyrian Dictionary was completed last year after 90 years of work, while the Demotic Dictionary, which does not include as much information as the Assyrian Dictionary, was completed in less than half the time. Scholars at the Oriental Institute are also working on a dictionary of Hittite, a language once spoken in Anatolia (present-day Turkey).

“The last four decades have seen a real explosion of Demotic studies, with more scholars focusing on this material, and great leaps in our understanding of this late version of the Egyptian language,” said Gil Stein, director of the Oriental Institute. “The Chicago Demotic Dictionary is reaching completion at the perfect time to have an enormous impact on our understanding of Egyptian civilization in the final few centuries, when it still flourished as a vibrant and unique culture.

Courtesy of Oriental Institute Museum

The work began in 1975 as a supplement and update to Wolja Erichsen’s Demotisches Glossar, published in 1954. The dictionary is based on texts in Demotic that were published by scholars from 1955 to 1979, and lists new words not included in Erichsen’s work as well as new uses of words included there. The words are listed in the dictionary with references to how they were used in documents.

The use of computers helped speed the process of preparing the dictionary because it allowed scholars to reproduce the cursive script of Demotic electronically and add information in Roman fonts. By providing photographs, or facsimiles of the script, the dictionary provides an exact representation of the way people wrote the language.

The final entry for “S” has been completed, and 24 other letters are online. Eventually there will be a published dictionary primarily for university libraries.

Much of Johnson’s own work deals with scholarship on women who lived during a period of transition in Egyptian society. Although the rulers in the classical worlds of Rome and Greece frequently minimized the role of women in their cultures, the Egyptians had an idea much closer to equality of the sexes.

On a wall in the Oriental Institute Museum, for instance, is a papyrus scroll on display bearing the text of an annuity written in Demotic. Annuities were written by a husband to a wife to acknowledge money she had brought into marriage and also guaranteeing to provide a set amount of food plus money for clothing for her use each year during their marriage.

The documents in Demotic show that people during the period continued the respect for women that had been typical of earlier times in Egyptian history. Women could own property, for instance, and also had the right to divorce their husbands.

Another Demotic scholar at the Oriental Institute is Brian Muhs, who has worked on tax records written in demotic, both official government tax records, and tax receipts issued to taxpayers.

Authorities conducted censuses, which were used to collect taxes with different rates for men and women; compulsory labor requirements for men only, such as digging ditches; and professional taxes for people practicing a profession. There were sales taxes and taxes collected as grain from harvests.

“The government often leased the collection of taxes to the highest bidder, who was required to pay the amount of the bid to the government regardless of how much tax they collected,” said Muhs, associate professor at the Oriental Institute.

“To protect the taxpayers from overzealous tax collectors, the tax collectors were required to issue tax receipts to taxpayers upon payment of their taxes,” he explained. “Multiple tax receipts for the same individuals frequently survive, because individuals usually kept their tax receipts together for multiple years.”

Photo by Jason Smith

The literature also has proverbs rich with folk wisdom, carried in instructions that are left on papyrus. They provide insights in the way people were expected to behave.“Do not sit down before a dignitary,” the instructions caution, for instance.

Other examples of common sense include: “Pride and arrogance are the ruin of their owner”; “Do not sit or stand still in an undertaking which is urgent”; and “Money is the snare the god has placed on earth for the impious man so that he should worry daily.”

Prof. Friedhelm Hoffmann of the Institute for Egyptology at the University of Munich said: “The Demotic texts play a crucial role in providing the necessary insights into the time when the classical world of Greece and Rome had close contacts to the Egyptian culture.

“The stories Herodotus (fifth-century B.C.) tells about Egyptian kings of the second-millennium B.C., for example, have to be understood not in the light of how the second millennium really was, but in the light of what the Egyptians of the fifth-century B.C. thought and narrated about these ancient times,” he explained.

“I myself have been using the Chicago Demotic Dictionary since the first letters were published, not only for looking up words and but also finding their meaning,” Hoffmann said.

The publication of the dictionary has doubled the number of words known in Demotic, and subsequent translations and publications will produce even more, Hoffmann said.

That work may prompt a need for a CDD 2.0, he said.

Contacts and sources:

William Harms

University of Chicago

Hunting For Neutrinos

June 27th, 2013

By Alton Parrish.

Every second, trillions of particles called neutrinos pass through your body. These particles have a mass so tiny it has never been measured, and they interact so weakly with other matter that it is nearly impossible to detect them, making it very difficult to study their behavior.

Since arriving at MIT in 2005, Joseph Formaggio, an associate professor of physics, has sought new ways to measure the mass of neutrinos. Nailing down that value — and answering questions such as whether neutrinos are identical to antineutrinos — could help scientists refine the Standard Model of particle physics, which outlines the 16 types of subatomic particles (including the three neutrinos) that physicists have identified.

Those discoveries could also shed light on why there is more matter than antimatter in the universe, even though they were formed in equal amounts during the Big Bang.

“There are big questions that we still haven’t answered, all centered around this little particle. It’s not just measuring some numbers; it’s really about understanding the nature of the equation that explains particle physics. That’s really exciting,” Formaggio says.

Joseph Formaggio

Photo credit: M. Scott Brauer

Formaggio, the only child of Italian immigrants, was the first in his family to attend college. Born in New York City, he spent part of his childhood in Sicily, his parents’ homeland, before returning to New York. From an early age, he was interested in science, especially physics and math.

At Yale University, he studied physics but was also interested in creative writing. The summer after his freshman year, in search of a summer job, he “called every publishing house in New York City, all of which resoundingly rejected me,” he says. However, his call to the Yale physics department yielded an immediate offer to work with a group that was doing research at the Collider Detector at Fermilab. That led to a senior thesis characterizing the excited states of the upsilon particle, which had recently been discovered.

As a student, Formaggio was drawn to both particle physics and astrophysics. At Columbia University, where he earned his PhD, he started working in an astrophysics group that was studying dark matter. Neutrinos were then thought to be a prime candidate for dark matter, and the mysterious particles intrigued Formaggio. He eventually joined a neutrino research group at Columbia, which included Janet Conrad, a professor who is now at MIT.

While a postdoc at the University of Washington, Formaggio participated in experiments at the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (SNO), located in a Canadian nickel mine some 6,800 feet underground. Those were the first experiments to show definitively that neutrinos have mass — albeit a very tiny mass.

Until then, “there were definitely hints that neutrinos undergo this process called oscillation where they transmute from one type to another, which is a signature for mass, but all the evidence was sort of murky and not quite definitive,” Formaggio says.

The SNO experiments revealed that there are three “flavors” of neutrino that can morph from one to the other. Those experiments “basically put the nail in the coffin and said that neutrinos change flavors, so they must have mass,” Formaggio says. “It was a big paradigm shift in thinking about neutrinos, because the Standard Model of particle physics wants neutrinos to be massless, and the fact that they’re not means we don’t understand it at some very deep level.”

Another possible discovery that could throw a wrench into the Standard Model is the existence of a fourth type of neutrino. There have been hints of such a particle but no definitive observation yet. “If you put in four neutrinos, the Standard Model is done,” Formaggio says, “but we’re not there yet.”

‘A giant electromagnetic problem’

In his current work, Formaggio is focused on trying to measure the mass of neutrinos. In one approach, he is working with an international team on a detector called KATRIN, located in a small town in southwest Germany. This detector, about the size of a large hangar, is filled with tritium, an unstable radioactive isotope. When tritium decays, it produces neutrinos and electrons. By measuring the energy of the electron released during the decay, physicists hope to be able to calculate the mass of the neutrino — an approach based on Einstein’s E=mc2 equation.

“Because energy is conserved, if you know how much you started out with and how much the electron took away, you can figure out how much the neutrino weighs,” Formaggio says. “It’s a very hard measurement but I like it because the experiment is a giant electromagnetic problem.”

The KATRIN detector is under construction and scheduled to begin taking data within the next two years. Formaggio is also developing another tritium detector, known as Project 8, which uses the radio frequency of electrons to measure their energies.

Formaggio hopes that one day, tritium-based detectors could be used to find neutrinos still lingering from the Big Bang, which would require even larger quantities of tritium.

“There are many holy grails in physics, and finding those neutrinos is definitely one of them. People look at the light from the Big Bang, but that’s actually closer to 300,000 years old, or thereabouts. Neutrinos from the Big Bang have been around since the first second of the universe,” Formaggio says.

Anne Trafton, MIT News Office

Prehistoric Paintings Reveal Native Americans’ Cosmology

June 26th, 2013By Alton Parrish.

Image credit: Jan Simek, Alan Cressler, Nicholas Herrmann and Sarah Sherwood/Antiquity Publications Ltd.The paintings reflected not only where they were painted, but contemplated the layers of their spiritual world, according to Jan Simek of the University of Tennessee at Knoxville. Simek, along with Nick Herrmann of Mississippi State University, Alan Cresser of the U.S. Geological Survey, and Sarah Sherwood at the University of the South who published their findings in the current issue of the journal Antiquities.

Archaeologists tended to minimize their culture in the past, underestimating the complexity, but work done by researchers such as Simek have brought to light just how complex their civilizations were, he said.

“They connected the dots,” Pluckhan said.

The city of Cahokia began around 600 AD across the Mississippi River from what is now St. Louis. Cahokia’s population may have reached 40,000 people, which would make it the largest city ever built in what is now the United States prior to the 1780s when Philadelphia’s population caught up. In 1250, Cahokia’s population of 15,000 matched London and Paris.

Cahokia was abandoned by the 15th century.

When Europeans arrived in the 16th century, the Mississippians had generally evolved or been replaced by the tribes or ethnic groups we now know as Cherokee or Cree or other groups. Anthropologists aren’t sure.

Before then, Pluckhan said, the Mississippians were loosely connected sociopolitical groups, usually associated with a chief, sometimes sharing languages.

The mounds were used as platforms for the chiefs’ houses or for the site of a religious building.

The oldest paintings are in caves, Simek said, some of them more than a mile-and-a-half inside the Earth, where the artists would have had to bring torches and supplies to do their work. Some of the caves were used for burials, but mostly they were sites of religious observance, and the art was part of the rituals.

Although the oldest art work includes the oldest cave art in North America and was dated to 6,000 years ago, most of the art work in the study was completed in the 11th-17th centuries.

The researchers explored 44 open air sites in Tennessee and 50 caves, some of which are located on private land. Some sites have been preserved, but some of the art is not. The paper deliberately avoided mentioning the specific location of any to protect them.

The artwork found on the walls of the caves reveals how the Mississipians thought about the world and universe around them, which was probably similar to earlier Native American religious structures, such as the Mayans, Simek said.

For the Mississippians, the cosmos were organized into levels or spheres, and humans occupied just one of those levels, Simek said. The others were occupied by spirits.

The paintings reflected the separation of spheres.

In the lower levels of their cosmology, the art showed malevolent spirits and transformative figures, including shape-changing humans, often turning into birds. The cave art depicted the lower depths. The paintings showed weapons, sometimes in acts of violence, including at least one with an ax coming out of a human head.

Above the humans were benevolent spirits that drove the weather and looked after the crops. The Mississippians relied on them for their existence and livelihood.

The surface paintings–the higher level–often were simpler, with human faces facing outward instead of in profile. They tended to have less detail, Simek said. One showed a man dancing with a rattle.

The art in the caves was done in black, using carbon for coloration; the ones on most rocks in the open air were red, using iron oxide (rust) for coloration. The subjects also reflected where the art was in relation to the world, Simek said.

“It is not surprising that they would attempt to connect the landscape of the mind with the landscape of nature,” Simek said.

Linking art to cosmology is not unique to these people, he said. The ancient Egyptians did it when they constructed their pyramids, the builders of Stonehenge may have done so as well, as did the builders of the great medieval cathedrals.

“Humans often in their religious beliefs divide the universe into various parts,” Simek said, “into sort of a strata–an upper world that humans rarely are part of; a lower world that humans are not a part of. Most often humans occupy the middle part of the world. And certain aspects of experience and aspects of this experience are attributed to those different layers.

“These folks are doing what is a common phenomenon,” he said.

By: Joel N. Shurkin

Researchers Use Video Game Tech To Control Roaches

June 25th, 2013

By University of North Carolina.

Photo credit: Alper Bozkurt)

The researchers have incorporated Microsoft’s motion-sensing Kinect system into an electronic interface developed at NC State that can remotely control cockroaches. The researchers plug in a digitally plotted path for the roach, and use Kinect to identify and track the insect’s progress. The program then uses the Kinect tracking data to automatically steer the roach along the desired path. Video of the system in actionis available here.

The program also uses Kinect to collect data on how the roaches respond to the electrical impulses from the remote-control interface. This data will help the researchers fine-tune the steering parameters needed to control the roaches more precisely.

“Our goal is to be able to guide these roaches as efficiently as possible, and our work with Kinect is helping us do that,” says Dr. Alper Bozkurt, an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at NC State and co-author of a paper on the work.

“We want to build on this program, incorporating mapping and radio frequency techniques that will allow us to use a small group of cockroaches to explore and map disaster sites,” Bozkurt says. “The autopilot program would control the roaches, sending them on the most efficient routes to provide rescuers with a comprehensive view of the situation.”

The roaches would also be equipped with sensors, such as microphones, to detect survivors in collapsed buildings or other disaster areas. “We may even be able to attach small speakers, which would allow rescuers to communicate with anyone who is trapped,” Bozkurt says.

Bozkurt’s team had previously developed the technology that would allow users to steer cockroaches remotely, but the use of Kinect to develop an autopilot program and track the precise response of roaches to electrical impulses is new.

The interface that controls the roach is wired to the roach’s antennae and cerci. The cerci are sensory organs on the roach’s abdomen, which are normally used to detect movement in the air that could indicate a predator is approaching – causing the roach to scurry away. But the researchers use the wires attached to the cerci to spur the roach into motion. The wires attached to the antennae send small charges that trick the roach into thinking the antennae are in contact with a barrier and steering them in the opposite direction.

The paper, “Kinect-based System for Automated Control of Terrestrial Insect Biobots,” will be presented at the Remote Controlled Insect Biobots Minisymposium at the 35th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society July 4 in Osaka, Japan. Lead author of the paper is NC State undergraduate Eric Whitmire. Co-authors are Bozkurt and NC State graduate student Tahmid Latif. The research was supported by the National Science Foundation.

Researchers Uncovers Late Bronze Age Fortress in Cyprus

June 22nd, 2013

By University of Cincinnati.

That research, by UC’s Gisela Walberg, professor of classics, will be presented at the annual workshop of the Cyprus American Archaeological Research Center in Nicosia, Cyprus, on June 25, 2011.

Since 2001, Walberg has worked in modern Cyprus to uncover the ancient city of Bamboula, a Bronze Age city that was an important trading center for the Middle East, Egypt and Greece. Bamboula, a harbor town that flourished between the 13th through the 11th century B.C., sits along a highway on the outskirts of the modern village of Episkopi, along the southwestern coast of Cyprus and near the modern harbor town of Limassol. The area thrived in part because the overshadowing Troodos Mountains contained copper, and the river below was used to transport the mined materials.

Overview of the excavation site in what was the ancient city of Bamboula, a Bronze Age city that was an important trading center for the Middle East, Egypt and Greece.

Credit: University of Cincinnati

Her most recent research at the site revealed the remnants of a Late Bronze Age (1500-750 B.C.) fortress that may have functioned to protect the urban economic center further inland, which does not seem to have been fortified.

Clues to the function of the structure were clear to Walberg. “It’s quite clear that it is a fortress because of the widths and strengths of the walls. No house wall from that period would have that strength. That would have been totally unnecessary,” she said, noting that one wall is 4.80 meters thick. “And it is on a separate plateau, which has a wonderful location you can look north to the mountains or over the river, and you can see the Mediterranean to the south — so you can see whoever is approaching.”

Remains of stairs leading up to a destroyed circular tower-like structure, which would have been convenient to look out over the area, were also found.

“We found the first walls, which we thought were interesting, in 2005,” Walberg said. “But, we continued, and this year, we found a staircase – actually we had found two steps before of a similar staircase, but this time we found a whole staircase.”

The remains of a staircase and lintel blocks at the late Bronze Age fortress that stood on the site.

Credit: University of Cincinnati

According to Walberg, the staircase seems to have been broken in a violent catastrophe, which throws lights on the early Late Bronze Age history in Cyprus, a period of which little is known but characterized by major social upheaval and cemeteries containing what a number of scholars have identified as mass burials.

The recent find is also particularly significant because there is another older site from the Middle Bronze Age nearby, within walking distance, of the fortress. Upriver exists remains of a large economic center, called Alassa, a center for trading agricultural products and metal.

“Our find, the fortress, fills the gap in time in between this early settlement and the very big, important economic center. It probably was the center, the core, from which urbanization began in the area,” Walberg said.

Walberg is currently the Marion Rawson Professor of Aegean Prehistory in the Department of Classics at the University of Cincinnati. Her fieldwork experience includes participation in excavations in Sweden, Crete and Cyprus. She has also participated in archaeological surveys in Greece and Italy, and directed an excavation of a Mycenaean citadel (Midea) in mainland Greece.

Walberg’s published works include 10 books and monographs. One is a report on the 1985-1991 excavations at Midea. She has also authored 81 articles and 20 reviews in American and international archaeological periodicals and lectured in many countries. Currently, Walberg is working on a book about the Bamboula excavations.

Credit: University of Cincinnati

Credit: University of Cincinnati

Contacts and sources:

M.B. Reilly

University of Cincinnati

Scientists Solve Riddle Of Strangely Behaving Magnetic Material

June 22nd, 2013By DOE U.S. Department of Energy.

The compound of lanthanum, cobalt and oxygen (LaCoO3) has been a puzzle for over 50 years, due to its strange behavior. While most materials tend to lose magnetism at higher temperatures, pure LaCoO3 is a non-magnetic semiconductor at low temperatures, but as the temperature is raised, it becomes magnetic. With the addition of strontium on the La sites the magnetic properties become even more prominent until, at 18 percent strontium, the compound becomes metallic and ferromagnetic, like iron.

“It’s just strange stuff. The material has attracted a lot of attention since about 1957, when people started picking it up and really studying it,” said Bruce Harmon, senior scientist at the Ames Laboratory. “Since then, there have been over 2000 pertinent papers published.”

Traditional theories to describe the compound’s behavior originated with physicist John B. Goodenough, who postulated that as temperature rises, the spin state of the d-electrons of cobalt changes, yielding a net magnetic moment.

“Back then it was more of a chemist’s atomic model of electron orbits that suggested what might be going on,” explained Harmon. “It’s a very local orbital picture and that theory has persisted to this day. It’s become more sophisticated, but almost all the theoretical descriptions are based on that model.”

But when Ames Laboratory research partners at the Argonne National Laboratory and the University of California, Santa Cruz performed X-ray absorption spectroscopy measurements of the material, the theory didn’t fit what they were observing.

Credit: Ames Laboratory

”They knew that we could calculate x-ray absorption and magnetic dichroism, so we started doing that. It is a case where we fell into doing what we thought was a routine calculation, and it turned out we discovered a totally different explanation,” said Harmon. “We found we could explain pretty much everything in really nice detail, but without explicitly invoking that local model,” said Harmon.

The scientists found that a small rhombohedral distortion of the LaCoO3 lattice structure, which had largely been ignored, was key.

“We found that the total electronic energy of the lattice depends sensitively on that distortion,” explained Harmon. “If the distortion becomes smaller (the crystal moves closer to becoming cubic), the magnetic state of the crystal switches from non-magnetic to a state with 1.3 Bohr magnetons per Co atom.”

Ames Laboratory scientists Bruce Harmon and Yongbin Lee partnered with the researchers at the Argonne National Laboratory and the University of California, Santa Cruz to publish a paper in Physical Review Letters, “Evolution of Magnetic Oxygen States in Sr-Doped LaCO3.”

This new understanding may help the further development of these materials, which are easily reduced to nanoparticles; these are finding use in catalytic oxidation and reduction reactions associated with regulation of noxious emissions from motor vehicles.

The research is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science through the Ames Laboratory.

The Ames Laboratory is a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science national laboratory operated by Iowa State University. The Ames Laboratory creates innovative materials, technologies and energy solutions. We use our expertise, unique capabilities and interdisciplinary collaborations to solve global problems.

Contacts and sources:

Laura Millsaps

DOE/Ames Laboratory

Drone Swarms Flying In Formation

June 22nd, 2013

By Alton Parrish.

Credit: ©Science China Press

Credit: ©Science China Press

In recent years, formation control of multiple UAVs has become a challenging interdisciplinary research topic, while autonomous formation flight is an important research area in the aerospace field. The main motivation is the wide range of possible military and civilian applications, where UAV formations could provide a low cost and efficient alternative to existing technology. Researchers and clinicians have developed many methods to address the formation problem. Despite all efforts, currently available formation control methods ignore network effects. The UAV group would perform their flight missions according to an existing database received by the navigation system and various sensors. Therefore, the stability of a UAV group is usually affected by the network characteristics, and there is an urgent need for network control strategies with better efficacy.

Trophallactic is a new swarm search algorithm. This new mechanism is based on the trophallactic behavior of social insects, animals and birds, such as ants, bees, wasps, sheep, dogs, sparrows and swallows. Trophallaxis is the exchange of fluid by direct mouth-to-mouth contact. Animal studies revealed that trophallaxis can reinforce the exchange and sharing of information between individual animals. By imitating that behavior and considering the communication requirements of the network control system, a network control method was proposed. The method was derived from the following example. A honeybee that finds the feeder fills its nectar crop with the offered sugar solution, and if the bee meets another bee on its way, there can be trophallactic contact. The higher the metabolic rate of the bee is, the higher this consumption rate will be. The attractive aspect of the trophallaxis mechanism is the ability to incorporate information transfer as a biological process and use global information to generate an optimal control sequence at each time step.

The virtual leader is employed in the formation flight model, and two trophallaxis strategies—the empty call and donation mechanisms—were considered to implement information transfer. In the process of formation, all UAVs, including the virtual leader, have the ability to conduct trophallaxis. The virtual leader sends updated task information and other UAVs update task information during their sampling period through the trophallaxis network.

Chinese And Japanese Researchers Find Evidence Of A New Particle

June 20th, 2013By Alton Parrish.

The two scientific collaborations, of Asian and other researchers around the world, published their finding in the journal Physical Review Letters . Together, they have identified 460 examples of the new structure.

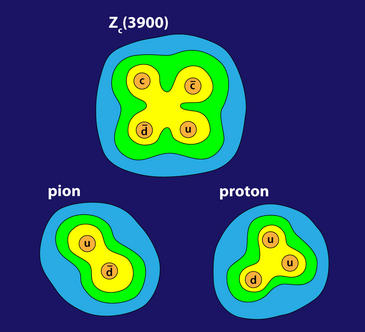

The recorded data suggest that Z c (3900) could be an unknown type of matter, consisting of four quarks. So far only known groups of two quarks or antiquarks, as the pions, for example, or of three quarks, such as protons have been found.

With the current information, the particle appears to have electric charge and at least one charmed quark and an anti-charm quark. The quartet is supplemented by a top quark and an anti-top quark, scientists suspect.

What to now confirm is that a four quark particle not for example the interaction of two quark with a pair each, or sporadic connections such essential constituents matter.

The discovery of Z c (3900) was the result of research with another particle, Y (4260), discovered in 2005. When considering its disintegration in the two colliders, physicists noticed a peak energy of about 3.9 gigaelectronvolts, about four times the weight of a proton. This suggests the existence of four-quark particle, a novelty in particle physics to be demonstrated.

City Of Ostia Found, Ancient Harbor Supplied Rome With Wheat

June 18th, 2013

By Alton Parrish.

Credit: © S. Keay

A French-Italian team led by Jean-Philippe Goiran, CNRS researcher, has tried to definitely verify the hypothetical location of the harbour, by using a new geological corer. This technology solves the problem of groundwater which makes this area rather difficult for archeologists to excavate beyond 2 m deep.

Two sediment cores have been extracted, showing a complete 12 m depth stratigraphy and the evolution of the harbour zone in 3 steps:

(2) 2- A middle layer, rich in grey silty-clay sediments, shows a typical harbour facies. According to calculations, the basin had a depth of 6.5 m at the beginning of its operation (dated between the 4th and 2d centuries BC). Previously considered as a river harbour that can only accommodate low draft boats, Ostia actually enjoyed a deep basin capable of receiving deep draft marine ships.

(3) 3 – Finally, the most recent stratum, composed of massive alluvium accumulations, shows the abandonment of the basin during the Roman imperial period. With radiocarbon dates, it is possible to deduce that a succession of major Tiber floods episodes of the Tiber finally came to seal the harbour of Ostia between the 2nd century BC and the 1st quarter of the 1st century AD (and this despite possible phases of dredging). At that time, the depth of the basin was less than 1 m and made any navigation impossible. It was then abandoned in favor of a new harbour complex built 3 km north of the Tiber mouth, called Portus. This alluvium layer fits with the geographer Strabo’s text (58 BC – 21/25 AD) who indicated the sealing of the harbour basin by sediments of the Tiber at that time (Geographica, 231-232).

The discovery of the river mouth harbour of Ostia, north of the city and west of the Imperial Palace, will help better understand the links between Ostia, its harbour and the ex-nihilo settling of Portus, initiated in 42 AD and completed in 64 AD under the reign of Nero. This gigantic 200 ha wide complex became the harbour of Rome and the largest ever built by the Romans in the Mediterranean.

Between the abandonment of the port of Ostia and the construction of Portus, researchers estimate that nearly 25 years have passed. Rome was the capital of the ancient Roman world and the first city to reach one million inhabitants. So how was it supplied with wheat during that period? The question arises now researchers.

(1) This work was also carried out in collaboration with the Maison Méditerranéenne des Sciences de l’Homme (CNRS / Aix-Marseille Université), the Universita Roma 3, the Institut Universitaire de France and received the support of the ANR (Agence Nationale de la Recherche).

Citation: J.-Ph. Goiran, F. Salomon, E. Pleuger, C. Vittori, I. Mazzini, G. Boetto, P. Arnaud, A. Pellegrino, décembre 2012, “Résultats préliminaires de la première campagne de carottages dans le port antique d’Ostie”, Chroniques des Mélanges de l’Ecole Française de Rome, vol. n°123-2.

Powdermet Partners With DOE & DOD To Develop Next-Gen Batteries

June 17th, 2013

By Audrey Neuman.

These partnerships including the U.S. Army, the U.S. Department of Energy and the U.S. Navy further validate the potential impact of these advanced materials. The disruptive material science platforms developed by Powdermet and its partners have applications in industries, such as Energy, Defense, and Transportation among others.

“Powdermet has been at the forefront of technical innovation for the past decade, and our expertise in nanotechnology and advanced materials development has attracted top-tier partners,” said Robert Miller, CEO of Abakan Inc. “The company is now focused on commercializing several of its technology platforms following our successful research and development which have shown very impressive results for these platforms. We expect to serve multi-billion dollar markets across a variety of industries.”

Powdermet’s EnCompTM Energetic nanocomposite materials improve both the energy density and power density of batteries. Powdermet has partnered with the U.S. Army to develop applications requiring instant-on storage of a large amount of electrical energy at high voltages for long periods of time without significant current leakage. Powdermet has utilized its nanoparticle synthesis and controlled dispersion processing capabilities to demonstrate melt-processable nanoparticle-filled engineered composite film dielectrics showing 20 to 30 J/cc of energy density, highlighting the opportunity for the technology to vastly improve energy storage technologies for the transportation and renewable energy sectors.

In addition to these initial defense applications, nanodielectric materials for smart grid applications are expected to represent a $500 million market by 2017 according toNanoMarkets. The nanodielectric materials are expected to have several other applications, replacing and enhancing batteries in the electric vehicle, consumer electronics and other industries, cumulating to a more than $1 billion market for nanodielectrics in the next five to seven years.

Additionally, Powdermet’s long-term collaboration with Michigan State University also received investment from the Department of Energy to further develop critical nanocomposite separators needed for ultra-high power density multivalent batteries based on ionic liquids. Multivalent batteries enable an order of magnitude increase in the power density of batteries, enabling the handling of high power loads in smaller, lighter, lower cost devices. This technology complements Powdermet’s ongoing efforts to develop encapsulated nanocomposite anode and cathode materials addressing needs within the $100 billion global advanced battery manufacturing value chain.

Finally, Powdermet’s MComPTM Microcomposite cermet (ceramic-metal) materials provide the friction and wear performance equivalent to advanced, diamond-like carbon coatings, but with the toughness, strength and formability of metals. Powdermet has partnered with the U.S. Navy to provide a solution to contamination issues in spherical plain airframe bearings using advanced coatings that have already been commercialized through Abakan subsidiary MesoCoat. These nanocomposite cermet materials have applications across the transportation, energy, military, construction and other sectors for reducing friction and extending the life of, or eliminating the need for lubricants, in highly stressed systems.

Abakan develops, manufactures, and markets advanced nanocomposite materials,innovative fabricated metal products and highly engineered metal composites for applications in the oil and gas, petrochemical, mining, aerospace and defense, energy, infrastructure and processing industries.

Baby Formula Linked To Stress And Disease Risk

June 15th, 2013

By Michael Bernstein.

Carolyn Slupsky and colleagues explain that past research showed a link between formula-feeding and a higher risk for chronic diseases later in life. Gaps exist, however, in the scientific understanding of the basis for that link.

The scientists turned to rhesus monkeys, stand-ins for human infants in such research, that were formula-fed or breast-fed for data to fill those gaps.

Their analysis of the monkeys’ urine, blood and stool samples identified key differences between formula-fed and breast-fed individuals. It also produced hints that reducing the protein content of infant formula might be beneficial in reducing the metabolic stress in formula-fed infants. “Our findings support the contention that infant feeding practice profoundly influences metabolism in developing infants and may be the link between early feeding and the development of metabolic disease later in life,” the study states.

7,000 BC: The Dawn Of Cinema

June 15th, 2013

By Alton Parrish.

Pitotti is a multimedia digital rock art exhibition in the South Lecture Room of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA).

It brings some of the earliest human figures in European rock art to life with interactive graphics, 3D printing and video games; exploring the potential links between the world of archaeology and the world of film, digital humanities and computer vision.

The images on display are just a fraction of the 300,000 rock engravings that act as an archive of nearly 10,000 years of human history at the UNESCO World Heritage Site in Valcamonica, detailing how a small clan of hunter-gatherers eventually became part of the Roman Empire.

The engravings were made from as early as 7,000BC and continued to be made right up till the 16th century AD, with the richest activity taking place in the Iron Age (1100BC-200BC, before the Roman Empire).

Now, a host of artists have injected digital life into these rock-art figures, with video projections, an ambient cinema and an interactive touch screen table where multiple visitors can explore and play with a digitised rock face.

A large projection of the Valcamonica is hooked up to a video-game style joystick which can be used to navigate the valley and discover the carvings, and detailed scans have allowed the creation of 3D printed panels which visitors can touch.

Dr Frederick Baker, Senior Research Associate at the McDonald Institute of Archaeological Research, said: “Human beings have engraved the rocks with their everyday lives and stories. It’s a kind of visual autobiography. Through the help of digitisation we discover this tribe and get insight into the symbols which actually adorn the rock, to get these symbols moving.

“These images created by humans depict animals to tell of hunting and aspects of everyday life. Computer visual science, film, 3D and graphic design explore ancient prehistoric art forms.

“Visitors can interact and discover with their fingers in a tactile manner that was impossible until today. Now in the 21st century digital art allows the rock art to move from the valley onto the screens and into the digital world that surrounds us.”

The exhibition grew from years of research by Dr Christopher Chippindale and Dr Frederick Baker, both members of the Cambridge University Prehistoric Picture Project. Pitoti is a word from the Lombard dialect and is a local word describing these engraved figures as “little puppets”.

Dr Chippindale said: “What European rock art gives us is the world of prehistoric Europeans, as they themselves experienced it and understood it. Our prehistoric ancestors chose to make engravings of animals, but few of plants. Many of deer, but few of sheep, and vast numbers of armed warriors in opposed pairs. Why? Because those aspects of their lives were vital and central to them.”

The images depicted also tell the story of how innovations spread across continents.

“Horses appear, as do ploughs and carts,” said Professor Graham Baker from the MacDonald Institute. “Their wheels are a huge innovation which leads later to chariots. The engravings of musical instruments remind us that the arts were also part of prehistoric life.”

According to Dr Baker, the link between the rock art and the digital animations are stronger than might be imagined.

He added: “Some of the humans and animals in the art are made in rather rigid forms. Others look to be in lively, animated motion – frozen at a certain moment as if they were stills from an animated cartoon. What the figures cannot do is move: there were no film cameras or animation studios in prehistoric times. But with our cameras and studios, today we can take the metaphor literally. So much the ancient artists could not do – working only with hammer and stone against tough resistant rock – our new digital technologies can.”

New State Of Matter Counter-Intuitive To Laws Of Physics

June 13th, 2013

By Alton Parrish.

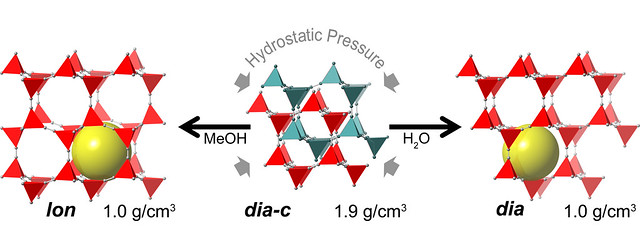

At the suburban Chicago laboratory, a group of scientists has seemingly defied the laws of physics and found a way to apply pressure to make a material expand instead of compress/contract.

“It’s like squeezing a stone and forming a giant sponge,” said Karena Chapman, a chemist at the U.S. Department of Energy laboratory. “Materials are supposed to become denser and more compact under pressure. We are seeing the exact opposite. The pressure-treated material has half the density of the original state. This is counterintuitive to the laws of physics.”

Because this behavior seems impossible, Chapman and her colleagues spent several years testing and retesting the material until they believed the unbelievable and understood how the impossible could be possible. For every experiment, they got the same mind-bending results.

“The bonds in the material completely rearrange,” Chapman said. “This just blows my mind.”

This discovery will do more than rewrite the science text books; it could double the variety of porous framework materials available for manufacturing, health care and environmental sustainability.

Scientists use these framework materials, which have sponge-like holes in their structure, to trap, store and filter materials. The shape of the sponge-like holes makes them selectable for specific molecules, allowing their use as water filters, chemical sensors and compressible storage for carbon dioxide sequestration of hydrogen fuel cells. By tailoring release rates, scientists can adapt these frameworks to deliver drugs and initiate chemical reactions for the production of everything from plastics to foods.

Pressure-induced transitions are associated with near 2-fold volume expansions. While an increase in volume with pressure is counterintuitive, the resulting new phases contain large fluid-filled pores, such that the combined solid + fluid volume is reduced and the inefficiencies in space filling by the interpenetrated parent phase are eliminated

Credit: ANL

“This could not only open up new materials to being porous, but it could also give us access to new structures for selectability and new release rates,” said Peter Chupas, an Argonne chemist who helped discover the new materials.

The team published the details of their work in the May 22 issue of the Journal of the American Chemical Society in an article titled “Exploiting High Pressures to Generate Porosity, Polymorphism, And Lattice Expansion in the Nonporous Molecular Framework Zn(CN)2 .”

The scientists put zinc cyanide, a material used in electroplating, in a diamond-anvil cell at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) at Argonne and applied high pressures of 0.9 to 1.8 gigapascals, or about 9,000 to 18,000 times the pressure of the atmosphere at sea level. This high pressure is within the range affordably reproducible by industry for bulk storage systems. By using different fluids around the material as it was squeezed, the scientists were able to create five new phases of material, two of which retained their new porous ability at normal pressure.

“By applying pressure, we were able to transform a normally dense, nonporous material into a range of new porous materials that can hold twice as much stuff,” Chapman said. “This counterintuitive discovery will likely double the amount of available porous framework materials, which will greatly expand their use in pharmaceutical delivery, sequestration, material separation and catalysis.”

The scientists will continue to test the new technique on other materials.

The research is funded by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

Contacts and sources:

Tona Kunz

DOE/Argonne National Laboratory

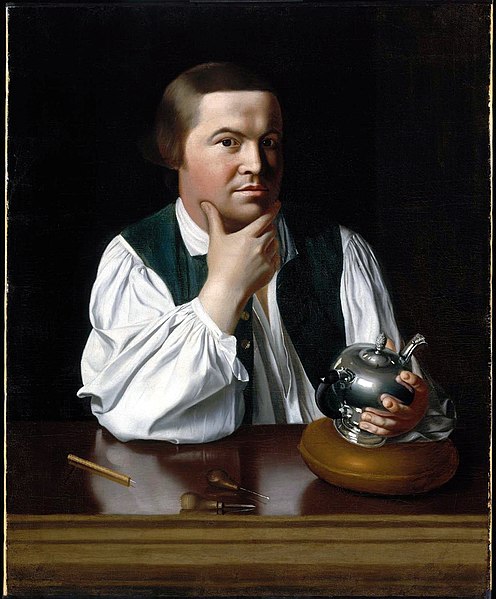

Metadata Would Have Caught Paul Revere!

June 13th, 2013

By Duke University.

Duke Sociologist Kieran Healey of the Kenan Institute for Ethics has written a brief primer on how one might use the sort of metadata available to National Security Agency snoops to figure out a burgeoning “terrorist” cell — in 1772 Boston.

Written in a sort of pseudo-18th century grammar (with mostly modern spellings, thankfully) Healy walks through the steps one would take to turn the membership lists of various organizations into a matrix of connections showing who the key agitators might be.

Using this “Social Networke Analysis,” but knowing nothing else about these names, he quickly fingers Sam Adams and Paul Revere as “persons of interest.”

The clever and instructive post has taken off on social media in the last day — reaching 100,000 views on Tuesday, and spreading even more strongly on Wednesday.

“I wanted to give non-specialists a sense of how the structural analysis of what’s being called ‘metadata’ works, and to show in a fun but hopefully telling way how much you can get out of that approach,” Healywrote in his blog the next day. “So I tried to emphasize that I was using one of the earliest, and (in retrospect) most basic methods we have, but one that still has the capacity to surprise people unfamiliar with (social network analysis).”

Unfrozen Mystery: Water Reveals A New Secret

June 11th, 2013

By Alton Parrish.

When water freezes into ice, its molecules are bound together in a crystalline lattice held together by hydrogen bonds. Hydrogen bonds are highly versatile and, as a result, crystalline ice reveals a striking diversity of at least 16 different structures.

In all of these forms of ice, the simple H2O molecule is the universal building block. However, in 1964 it was predicted that, under sufficient pressure, the hydrogen bonds could strengthen to the point where they might actually break the water molecule apart. The possibility of directly observing a disassociated water molecule in ice has proven a fascinating lure for scientists and has driven extensive research for the last 50 years. In the mid-1990s several teams, including a Carnegie group, observed the transition using spectroscopic techniques. However, these techniques are indirect and could only reveal part of the picture.

A preferred method is to “see” the hydrogen atoms–or protons–directly. This can be done by bouncing neutrons off the ice and then carefully measuring how they are scattered. However, applying this technique at high enough pressures to see the water molecule dissociate had simply not been possible in the past. Guthrie explained that: “you can only reach these extreme pressures if your samples of ice are really small. But, unfortunately, this makes the hydrogen atoms very hard to see.”

The Spallation Neutron Source was opened at Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee in 2006, providing a new and intensely bright supply of neutrons. By designing a new class of tools that were optimized to exploit this unrivalled flux of neutrons, Guthrie and his team–Carnegie’s Russell Hemley, Reinhard Boehler, and Kuo Li, as well as Chris Tulk, Jamie Molaison, and António dos Santos of Oak Ridge National Laboratory–have obtained the first glimpse of the hydrogen atoms themselves in ice at unprecedented pressures of over 500,000 times atmospheric pressure.

“The neutrons tell us a story that the other techniques could not,” said Hemley, director of Carnegie’s Geophysical Laboratory. “The results indicate that dissociation of water molecules follows two different mechanisms. Some of the molecules begin to dissociate at much lower pressures and via a different path than was predicted in the classic 1964 paper.”

“Our data paint an altogether new picture of ice,” Guthrie commented. “Not only do the results have broad consequences for understanding bonding in H2O, the observations may also support a previously proposed theory that the protons in ice in planetary interiors can be mobile even while the ice remains solid.”

And this startling discovery may prove to be just the beginning of scientific discovery. Tulk emphasized “being able to ‘see’ hydrogen with neutrons isn’t just important for studies of ice. This is a game-changing technical breakthrough. The applications could extend to systems that are critical to societal challenges, such as energy. For example, the technique can yield greater understanding of methane-containing clathrate hydrates and even hydrogen storage materials that could one day power automobiles”.

The group is part of Energy Frontier Research in Extreme Environments (EFree), an Energy Frontier Research Center headquartered at Carnegie’s Geophysical Laboratory.

Contacts and sources:

Carnegie Institution

Earthquake Acoustics Can Indicate If A Massive Tsunami Is Imminent

June 8th, 2013

By Alton Parrish.

Now, computer simulations by Stanford scientists reveal that sound waves in the ocean produced by the earthquake probably reached land tens of minutes before the tsunami. If correctly interpreted, they could have offered a warning that a large tsunami was on the way.

Although various systems can detect undersea earthquakes, they can’t reliably tell which will form a tsunami, or predict the size of the wave. There are ocean-based devices that can sense an oncoming tsunami, but they typically provide only a few minutes of advance warning.

Because the sound from a seismic event will reach land well before the water itself, the researchers suggest that identifying the specific acoustic signature of tsunami-generating earthquakes could lead to a faster-acting warning system for massive tsunamis.

Discovering the signal

The finding was something of a surprise. The earthquake’s epicenter had been traced to the underwater Japan Trench, a subduction zone about 40 miles east of Tohoku, the northeastern region of Japan’s larger island. Based on existing knowledge of earthquakes in this area, seismologists puzzled over why the earthquake rupture propagated from the underground fault all the way up to the seafloor, creating a massive upward thrust that resulted in the tsunami.

Direct observations of the fault were scarce, so Eric Dunham, an assistant professor of geophysics in the School of Earth Sciences, and Jeremy Kozdon, a postdoctoral researcher working with Dunham, began using the cluster of supercomputers at Stanford’s Center for Computational Earth and Environmental Science (CEES) to simulate how the tremors moved through the crust and ocean.

2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, An aerial view of damage in the Sendai region with black smoke coming from the Nippon Oil Sendai oil refinery

Retroactively, the models accurately predicted the seafloor uplift seen in the earthquake, which is directly related to tsunami wave heights, and also simulated sound waves that propagated within the ocean.

In addition to valuable insight into the seismic events as they likely occurred during the 2011 earthquake, the researchers identified the specific fault conditions necessary for ruptures to reach the seafloor and create large tsunamis.

The model also generated acoustic data; an interesting revelation of the simulation was that tsunamigenic surface-breaking ruptures, like the 2011 earthquake, produce higher amplitude ocean acoustic waves than those that do not.

The model showed how those sound waves would have traveled through the water and indicated that they reached shore 15 to 20 minutes before the tsunami.

“We’ve found that there’s a strong correlation between the amplitude of the sound waves and the tsunami wave heights,” Dunham said. “Sound waves propagate through water 10 times faster than the tsunami waves, so we can have knowledge of what’s happening a hundred miles offshore within minutes of an earthquake occurring. We could know whether a tsunami is coming, how large it will be and when it will arrive.”

Worldwide application

The team’s model could apply to tsunami-forming fault zones around the world, though the characteristics of telltale acoustic signature might vary depending on the geology of the local environment. The crustal composition and orientation of faults off the coasts of Japan, Alaska, the Pacific Northwest and Chile differ greatly.

“The ideal situation would be to analyze lots of measurements from major events and eventually be able to say, ‘this is the signal’,” said Kozdon, who is now an assistant professor of applied mathematics at the Naval Postgraduate School. “Fortunately, these catastrophic earthquakes don’t happen frequently, but we can input these site specific characteristics into computer models – such as those made possible with the CEES cluster – in the hopes of identifying acoustic signatures that indicates whether or not an earthquake has generated a large tsunami.”

Dunham and Kozdon pointed out that identifying a tsunami signature doesn’t complete the warning system. Underwater microphones called hydrophones would need to be deployed on the seafloor or on buoys to detect the signal, which would then need to be analyzed to confirm a threat, both of which could be costly. Policymakers would also need to work with scientists to settle on the degree of certainty needed before pulling the alarm.

If these points can be worked out, though, the technique could help provide precious minutes for an evacuation.

The study is detailed in the current issue of the journal The Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America.

Eric Dunham, Geophysics

Bjorn Carey, Stanford News Service

Where Trash And Garbage Accumulates In The Deep Sea

June 5th, 2013

By Alton Parrish.

For this study, research technicians searched the VARS database to find every video clip that showed debris on the seafloor. They then compiled data on all the different types of debris they saw, as well as when and where this debris was observed.

Deep-sea currents wrapped this plastic bag around a deep-sea gorgonian coral 2,115 meters (almost 7,000 feet) below the ocean surface in Astoria Canyon, off the Coast of Oregon.

Image: ©2006 MBARI

In total, the researchers counted over 1,500 observations of deep-sea debris, at dive sites from Vancouver Island to the Gulf of California, and as far west as the Hawaiian Islands. In the recent paper, the researchers focused on seafloor debris in and around Monterey Bay—an area in which MBARI conducts over 200 research dives a year. In this region alone, the researchers noted over 1,150 pieces of debris on the seafloor.

The largest proportion of the debris—about one third of the total—consisted of objects made of plastic. Of these objects, more than half were plastic bags. Plastic bags are potentially dangerous to marine life because they can smother attached organisms or choke animals that consume them.

Metal objects were the second most common type of debris seen in this study. About two thirds of these objects were aluminum, steel, or tin cans. Other common debris included rope, fishing equipment, glass bottles, paper, and cloth items.

The researchers found that trash was not randomly distributed on the seafloor. Instead, it collected on steep, rocky slopes, such as the edges of Monterey Canyon, as well as in a few spots in the canyon axis. The researchers speculate that debris accumulates where ocean currents flow past rocky outcrops or other obstacles.

A tangle of rope and fishing gear lies on the seafloor about 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) deep in Monterey Canyon.

Image: ©2012 MBARI

The researchers also discovered that debris was more common in the deeper parts of the canyon, below 2,000 meters (6,500 feet). Schlining commented, “I was surprised that we saw so much trash in deeper water. We don’t usually think of our daily activities as affecting life two miles deep in the ocean.” Schlining added, “I’m sure that there’s a lot more debris in the canyon that we’re not seeing. A lot of it gets buried by underwater landslides and sediment movement. Some of it may also be carried into deeper water, farther down the canyon.”

In the same areas where they saw trash on the seafloor, the researchers also saw kelp, wood, and natural debris that originated on land. This led them to conclude that much of the trash in Monterey Canyon comes from land-based sources, rather than from boats and ships.

Although the MBARI study also showed a smaller proportion of lost fishing gear than did some previous studies, fishing gear accounted for the most obvious negative impacts on marine life. The researchers observed several cases of animals trapped in old fishing gear.

Other effects on marine life were more subtle. For example, debris in muddy-bottom areas was often used as shelter by seafloor animals, or as a hard surface on which animals anchored themselves. Although such associations seem to benefit the individual animals involved, they also reflect the fact that marine debris is creating changes in the existing natural biological communities.

A young rockfish hides out in a discarded shoe, 472 meters (1,548 feet) deep in San Gabriel Canyon, off Southern California.

Image: ©2010 MBARI

To make matters worse, the impacts of deep-sea trash may last for years. Near-freezing water, lack of sunlight, and low oxygen concentrations discourage the growth of bacteria and other organisms that can break down debris. Under these conditions, a plastic bag or soda can might persist for decades.

MBARI researchers hope to do additional research to understand the long-term biological impacts of trash in the deep sea. Working with the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, they are currently finishing up a detailed study of the effects of a particularly large piece of marine debris—a shipping container that fell off a ship in 2004.

During research expeditions, researchers occasionally retrieve trash from the deep sea. However, removing such debris on a large scale is prohibitively expensive, and can sometimes do more damage than simply leaving it in place.

Schlining noted, “The most frustrating thing for me is that most of the material we saw—glass, metal, paper, plastic—could be recycled.” She and her coauthors hope that their findings will inspire coastal residents and ocean users to recycle their trash instead of allowing it to end up in the ocean. In the conclusion of their article, they wrote, “Ultimately, preventing the introduction of litter into the marine environment through increased public awareness remains the most efficient and cost-effective solution to this dilemma.”

Kim Fulton-Bennett

Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI)