Posts by AltonParrish:

Cosmic Doomsday: Dark Energy, The Fate Of The Universe And The End Of Earth

July 24th, 2012By Alton Parrish.

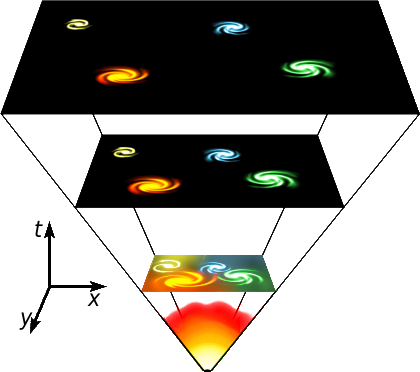

Dark energy makes up about 70 percent of the current content of the Universe and thus holds the ultimate fate of our Universe. Several possible scenarios are possible depending on the properties of dark energy; one is that the Universe will end in a so-called big rip. This interesting topic was recently explored by five researchers from the University of Science and Technology of China, the Institute of Theoretical Physics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Northeastern University, and Peking University. Their work, entitled “Dark energy and fate of the Universe”, was published in Sci China-Phys Mech Astron 2012, Vol. 55 No. 7.

Credit:Wikipedia

In the absence of a consensus on what dark energy is, a phenomenological description of the equation-of-state parameter w—the ratio of pressure and density of dark energy—provides an important means for investigating dark energy dynamics. Properties of dark energy will decide the ultimate fate of the Universe. In particular, if w<-1 at some time in the future, dark energy density will grow to infinity in finite time, and its gravitational repulsion will tear apart all the objects in the Universe. This “big rip” (or “cosmic doomsday”) scenario is the major focus of the paper. “We want to infer from the current data what the worst fate would be for the Universe”, said the authors.

Sumatra 8.6 Mega-Earthquake Largest Ever Recorded, Highest Resolution Of Underwater Rupture

July 24th, 2012By Alton Parrish.

The powerful magnitude-8.6 earthquake that shook Sumatra on April 11, 2012, was a seismic standout for many reasons, not the least of which is that it was larger than scientists thought an earthquake of its type could ever be. Now, researchers from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) report on their findings from the first high-resolution observations of the underwater temblor, they point out that the earthquake was also unusually complex—rupturing along multiple faults that lie at nearly right angles to one another, as though racing through a maze. according to Kimm Fesenmaier of Caltech.

“>

Credit: Caltech/Meng et al.

“>

“>

“> “>

“>

Credit: Caltech/Meng et al

“This part of the oceanic plate has fracture zones and other structures inherited from when the seafloor formed here, over 50 million years ago,” says Joann Stock, professor of geology at Caltech and another coauthor on the paper. “However, surprisingly, this earthquake just ruptured across these features, as if the older structure didn’t matter at all.”

Meng emphasizes that it is important to learn such details from previous earthquakes in order to improve earthquake-hazard assessment. After all, he says, “If other earthquake ruptures are able to go this deep or to connect as many fault segments as this earthquake did, they might also be very large and cause significant damage.”

Along with Meng, Ampuero, Tsai, and Stock, additional Caltech coauthors on the paper, “An earthquake in a maze: compressional rupture branching during the April 11 2012 M8.6 Sumatra earthquake,” are postdoctoral scholar Zacharie Duputel and graduate student Yingdi Luo. The work was supported by the National Science Foundation, the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the Southern California Earthquake Center, which is funded by the National Science Foundation and the United States Geological Survey.

Saturn’s Strange Moon: River Networks On Titan Point To A Puzzling Geologic History

July 22nd, 2012By Alton Parrish.

Findings suggest the surface of Saturn’s largest moon may have undergone a recent transformation.

For many years, Titan’s thick, methane- and nitrogen-rich atmosphere kept astronomers from seeing what lies beneath. Saturn’s largest moon appeared through telescopes as a hazy orange orb, in contrast to other heavily cratered moons in the solar system.

In 2004, the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft — a probe that flies by Titan as it orbits Saturn — penetrated Titan’s haze, providing scientists with their first detailed images of the surface. Radar images revealed an icy terrain carved out over millions of years by rivers of liquid methane, similar to how rivers of water have etched into Earth’s rocky continents.

While images of Titan have revealed its present landscape, very little is known about its geologic past. Now researchers at MIT and the University of Tennessee at Knoxville have analyzed images of Titan’s river networks and determined that in some regions, rivers have created surprisingly little erosion. The researchers say there are two possible explanations: either erosion on Titan is extremely slow, or some other recent phenomena may have wiped out older riverbeds and landforms.

“It’s a surface that should have eroded much more than what we’re seeing, if the river networks have been active for a long time,” says Taylor Perron, the Cecil and Ida Green Assistant Professor of Geology at MIT. “It raises some very interesting questions about what has been happening on Titan in the last billion years.”

A paper detailing the group’s findings will appear in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Planets.

What accounts for a low crater count?

Compared to most moons in our solar system, Titan is relatively smooth, with few craters pockmarking its facade. Titan is around four billion years old, about the same age as the rest of the solar system. But judging by the number of craters, one might estimate that its surface is much younger, between 100 million and one billion years old.

What might explain this moon’s low crater count? Perron says the answer may be similar to what happens on Earth.

“We don’t have many impact craters on Earth,” Perron says. “People flock to them because they’re so few, and one explanation is that Earth’s continents are always eroding or being covered with sediment. That may be the case on Titan, too.”

For example, plate tectonics, erupting volcanoes, advancing glaciers and river networks have all reshaped Earth’s surface over billions of years. On Titan, similar processes — tectonic upheaval, icy lava eruptions, erosion and sedimentation by rivers — may be at work.

But identifying which of these geological phenomena may have modified Titan’s surface is a significant challenge. Images generated by the Cassini spacecraft, similar to aerial photos but with much coarser resolution, are flat, depicting terrain from a bird’s-eye perspective, with no information about a landform’s elevation or depth.

Images from the Cassini mission show river networks draining into lakes in Titan’s north polar region.

Image: NASA/JPL/USGS

“It’s an interesting challenge,” Perron says. “It’s almost like we were thrown back a few centuries, before there were many topographic maps, and we only had maps showing where the rivers are.”

Charting a river’s evolution

Perron and MIT graduate student Benjamin Black set out to determine the extent to which river networks may have renewed Titan’s surface. The team analyzed images taken from Cassini-Huygens, and mapped 52 prominent river networks from four regions on Titan. The researchers compared the images with a model of river network evolution developed by Perron. This model depicts the evolution of a river over time, given variables such as the strength of the underlying material and the rate of flow through the river channels. As a river erodes slowly through the ice, it transforms from a long, spindly thread into a dense, treelike network of tributaries.

Black compared his measurements of Titan’s river networks with the model, and found the moon’s rivers most resembled the early stages of a typical terrestrial river’s evolution. The observations indicate that rivers in some regions have caused very little erosion, and hence very little modification of Titan’s surface.

“They’re more on the long and spindly side,” Black says. “You do see some full and branching networks, and that’s tantalizing, because if we get more data, it will be interesting to know whether there really are regional differences.”

Going a step further, Black compared Titan’s images with recently renewed landscapes on Earth,

including volcanic terrain on the island of Kauai and recently glaciated landscapes in North America. The river networks in those locations are similar in form to those on Titan, suggesting that geologic processes may have reshaped the moon’s icy surface in the recent past.

Oded Aharonson, a professor of planetary science at the California Institute of Technology, says analyzing geologic processes on Titan may help scientists understand how rivers form. “Besides Earth, Titan is the only world where we see active river networks forming as a result of an active hydrologic cycle,” Aharonson says. “The finding suggests the process of river erosion on Titan is currently responding to resurfacing or resetting of the surface.”

“It’s a weirdly Earth-like place, even with this exotic combination of materials and temperatures,” Perron says. “And so you can still say something definitive about the erosion. It’s the same physics.”

This research was supported by NASA’s Cassini Data Analysis Program.

Contacts and sources:

Jennifer Chu, MIT News Office

The Lost Pyramid of El Zotz Uncovered, Yields Insight Into Mayan Religion

July 21st, 2012By Alton Parrish.

Diablo Pyramid Found: El Zotz Masks Yield Insights Into Maya Beliefs

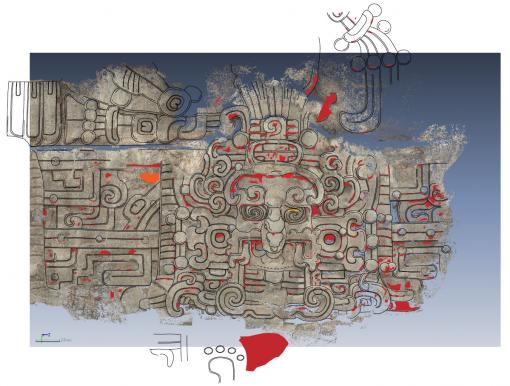

Credit: Brown University

The team began uncovering the temple, called the Temple of the Night Sun, in 2009. Dating to about 350 to 400 A.D., the temple sits just behind the previously discovered royal tomb, atop the Diablo Pyramid. The structure was likely built after the tomb to venerate the leader buried there.

Houston says that through this find, much of it pristinely preserved, researchers are gaining a significant amount of new information about the Maya civilization.

“The Diablo Pyramid is one of the most ambitiously decorated buildings in ancient America,” Houston says. “The stuccos provide unprecedented insight into how the Maya conceived of the heavens, how they thought of the sun, and how the sun itself would have been grafted onto the identity of kings and the dynasties that would follow them.” This latest discovery was made public earlier today during a press conference in Guatemala City, hosted by the Instituto de Antropologia e Historia de Guatemala, which authorized the work. Houston says the team is still in the beginning stages of the temple’s excavation, with more than 70 percent still to be uncovered. The Maya later built additional levels on top of the original structure, which helped to preserve the stuccos, but this also makes excavation more difficult. While excavating the tomb in 2009, Houston and his team discovered a small portion of the carvings peeking out from looter’s tunnels that had been dug several decades earlier. The archaeologists have only been able to clear narrow tunnels around the building to get a look at the masks and other carvings. There are several sections, including whole sides, an area of the roof, and the base still to be excavated. To get a better idea of what the building would have looked like in its original form, Houston is working with a team from the Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies (CAST) at the University of Arkansas, which uses photogrammetric techniques to create 3-D images of the stuccos. Houston is using those images, as well as hundreds of color photographs taken during the excavation, to create drawings of the building.Renderings indicate that a large solid platform made up the base of the pyramid, which consisted of two or three narrower terraces with the temple sitting at the top. The previously discovered tomb sits just beneath the main platform. A sanctuary was eventually built on top of the tomb to offer protection to the space. Houston says that at one time most of the temple would have been covered in ornate stuccos and that it is possible much of it has survived.

The excavation of the El Zotz site became more important last year, when it was named one of the World Monuments Fund’s 67 international cultural heritage sites at risk. The site is known for one of the very few carved wooden lintels with hieroglyphic text to have survived from pre-Colombian Mesoamerica.

Credit: Arturo Godoy

The team is learning much more about the temple’s purpose. Sitting on a high escarpment overlooking the main part of El Zotz, an ancient Maya city, the pyramid would have been a spectacular presence 1,600 years ago, according to Houston. Painted a saturated red, the temple was intended to announce its presence and the power of the ruling dynasty. It would have been at its brightest during the rising and setting of the sun and visible up to 15 miles away. The stucco masks on the walls of the temple appear to depict several celestial beings, including the sun, which the Maya thought of as a god (“K’inich Ajaw”). Standing five feet tall, several of the masks illustrate different phases of the sun as it moves from east to west in the sky over the course of the day. One mask displays fish-like characteristics, a representation of the rising sun on the horizon, which the Maya associated with the Caribbean to the east. Jeweled bands running between each mask contain archaic representations of Venus and other planets acting as the sky in this solar representation. “The sun was a key element of Maya rulership,” Houston says. “It was an icon which they linked very deliberately to royal lines, royal identity, and royal power. It’s the most dominant celestial feature. It’s something that rises every day and penetrates into all nooks and crannies, just as royal power presumably would. This building is one that celebrates this close linkage between the king and this most powerful and dominate of celestial presences.” The structure was built during a challenging time in the Maya world. The people of El Zotz and Tikal, another large Maya city nearby, were, for the first time, experiencing contact with and intrusions from the people of Teotihuacan, ancient America’s largest metropolis located near modern-day Mexico City. The pyramid may have been erected to signal local power at a time of intrusion and political turbulence. Another finding indicates that the Maya saw the building as a living being rather than just simply a physical structure. At one point, possibly when the Maya were preparing to add new construction to the existing building, the nose and mouths of the masks, as well as identifying glyphs on the forehead diadems, were systematically mutilated, according to Houston, as a way to deactivate the building.Despite the obvious care that was taken in constructing the building, it wasn’t used for long. Houston says evidence at the site shows that the building was abandoned sometime in the A.D. 400s, possibly because of a break in the dynastic order.

Houston, a 2008 MacArthur fellow, is the Dupee Family Professor of Social Science and professor of anthropology at Brown.

Houston’s co-director of the site has been Edwin Román, a Ph.D. candidate at the Long Institute of Latin American Studies at the University of Texas–Austin. They are working with a group of Brown graduate students and researchers, including Thomas Garrison, a former postdoctoral fellow at the Joukowsky Institute and the Department of Anthropology and currently on staff at the University of Southern California, and Sarah Newman, Nicholas Carter, Yeny Gutiérrez, and Boris Beltrán. Photography was done by Arturo Godoy and Alexa Rubinstein.

Fieldwork in 2012 was directed by Edwin Román and Thomas Garrison, with Houston as scientific adviser.

The work at El Zotz has been supported by funding from the National Science Foundation, the National Endowment for the Humanities, private sources, and, for the 2012 field season, by PACUNAM, a Guatemalan charity.

Contacts and sources:

Courtney Coelho

Brown University