Posts by ArizHuseynov:

Russia’s Relations with Post-Soviet Republics: A Neo-Gramscian Approach

October 22nd, 2014

By Ariz Huseynov.

… whilst Marxism has always offered an integrated approach . . . historical materialism has tended to become marginalized from many of the major debates in international studies.[1]

A considerable attention has been given to the international aspects of Gramsci’s works, within the scholarly public in last decades One can, however, hardly argue about its equal popularity with mainstream International Relations theories, which still dominant in the field of study. Thus the goal in this paper is to develop the Neo-Gramscian approach, as a particular form of Marxism, as a valid theory of IR. To do that, first, I will highlight what makes the approach and its main concepts theoretically attractive, in comparison with mainstream IR theories. Then, to support the argument, I will apply it to Russia and its relations with post-Soviet republics in the period between the early 1990s and second half of 2000s. In this regard, the work by Owen Worth[2], which makes Gramscian analysis of Russia and its position within the global order, is valuable, especially when considering the developments within Russia.

Neo-Gramscian Theory of IR

Gill (1993) explains the marginalization of Marxism, in general, and Gramscianism, in particular, with the dominance of the US theories in IR and with the decline of left-wing ideas after the developments in USSR and East Europe during the 1980s and 90s that reinforced this tendency further. [3] But, indeed, Gramscian approach, as we shall see, provides much more complex account of IR, in compare with orthodox theories.

In Smith’s words, ‘based on a prior set of distinctions between inside and outside, economics and politics, public and private’, mainstream IR ‘focuses on some inequalities, but deems others to lie outside the international political realm since they are defined as domestic, or economic, or private’.[4] Moreover, Gramsci himself criticized mainstream theories referring to them, whether it is ‘right’ (‘realism’) or ‘left’ (‘idealism’, ‘liberalism’, ‘functionalism’), as an ‘idealist philosophy’ for their ‘radical separation between force and consensus’ and argued these forms of rule are interrelated.[5] These limitations make it difficult to reflect and analyze the ‘complex international events through a very narrow set of theoretical lenses’.[6] Unlike mainstream theories, Neo-Gramscian approach, does not limit itself, making these distinctions, and recognizes interplay between domestic and international, coercion and consensus politics and economics and etc…

The main contribution of the Neo-Gramscian approach to the study of IR is, among others, its central concept of hegemony. Hegemony refers to a form of dominance but differs from mainstream realist usage which is about the dominance of one state over the others. Although dominance in these terms might be necessary, it is not enough for hegemony, which is more ‘consensual’ order than the ‘coercive’.[7] Power relations between ‘weak’ and ‘strong’ through the ‘coercion’ and/or ‘consent’ is better explained in Cox’s words:

There is enforcement potential in the material power relations underlying any structure, in that the strong can clobber the weak if they think it necessary. But force will not have to be used in order to ensure the dominance of the strong to the extent that the weak accept the prevailing power relations as legitimate. This the weak may do if the strong see their mission as hegemonic and not merely dominant dictatorial, that is, if they are willing to make concessions that will secure the weak’s acquiescence in their leadership and if they can express this leadership in terms of universal or general interests, rather than just as serving their own particular interests.[8]

Hegemony can be observed in three levels of activity: ‘social relations of production’; ‘forms of state’; and ‘world orders’ and all these levels reciprocally affect each other: [9]

Social relations of production gives rise for certain ‘social forces’, social forces in turn shape ‘forms of state’ and finally the ‘world order’ is influenced by the forms of states.[10] Accordingly, in the case of Russia’s relations with other post-Soviet countries, social relations of production and its impact on the form of state in Russia, and what parallels might be derived between these levels and Russia’s external relations will be analyzed.

Hegemony, “may expand beyond a particular social order to move outward” to the relations with other states after being established within any particular state.[11] Cox argues that “Institutions, whether domestically or internationally, may become the anchor for such a hegemonic strategy since they lend themselves both to the representations of diverse interests and to the universalization of policy”.[12] In another article, Cox gives more detailed account of international organizations as mechanism of hegemony, that, they:

-embody the rules which facilitate the expansion of hegemonic world orders;

-are themselves the product of the hegemonic world order;

-ideologically legitimate the norms of the world order

-co-opt the elites from peripheral countries;

-absorb counter-hegemonic idea[13]

In the case of Russia, this framework will be useful to assess the role of Russian-led regional international organization, Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), in the predominant order of the region.

For the purpose it is worth to mention the concepts of ‘transformismo’ and ‘Caeserism’ that has been developed by Worth, from their initial form used by Gramsci, and applied to Russia. ‘Transformismo’ refers to “how a set of ideas within a state have been gradually formed, harmonised and normalised to consolidate a hegemonic change”.[14] Through the process of ‘Transformismo’ a hegemonic project may attract diverse forms of opposition. For instance, in international relations it might be said of the state that makes reforms to fit a prevailing hegemonic order. ‘Caesarism’ is when ‘transformismo’ stays short in consolidating hegemonic change in states with weak civil society, and thus, the authoritarian methods are being applied.[15]

Gramscian account of Russian dominance in the Post-Soviet ‘world’

To understand the present role of Russia in post soviet world and its attempts to build hegemony over this ‘world’, it is important to consider the Soviet period and the relations within the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The Union was Moscow-centred and all other Socialist Republics were part of this hegemonic order established by Moscow, although by means of authoritarian, or in Gramsci’s words, ‘Caesarist’ strategies.[16] As Worth puts it “the ideological constructions that the Soviet Union was founded upon brought forms of hegemonic stability within soviet society”.[17] However, in the late 1980s, the things suddenly began to change and:

“… as the final manoeuvre by Gorbachov demonstrated the historical diverse collection of social forces within the USSR were finally given time and space to bubble at the surface, that made it even more difficult for any successive post-Soviet state to pacify”.[18]

Worth continues that the crisis of hegemony after the collapse of USSR demonstrated itself both within the emerging Russian Federation and between newly independent post-Soviet states. Nevertheless, despite the difficulties, post-Soviet Russia aimed, as we will see, not only at pacifying the diversities, but also at (re)establishing the hegemonic order within the country and in its relations with other post-Soviet states.

Here, taking Cox’s ‘triangle’ of ‘social relations of production’, ‘forms of state’, and ‘world order’ as a guide, as a point of departure it is worth, first, to look at social relations within Russia, which, in its turn, will make it easy to understand Russia’s form of state and, subsequently, its relations with other post-soviet countries.

‘Social relations of Production’, ‘Social Forces’ and ‘form of state’ in Russia

Russia consists of diverse and competing ideological, social and economic positions by the different social groups that exist within the country since the fall of USSR. Lester, a political theorist and Russian specialist, argues that “the diversity of ideological opinion and movement in post-communist Russia should be seen as a battle between hegemonic strategies, in which the prize represents the heartland of Russian civil society”.[19] Referring to Gramscian scholars, Lester argues that social forces can achieve a hegemonic role only if they gain the consent of politicized institutions. However, it should be mentioned that according to Gramsci a social forces that gain a dominant role, main source of which is an advantaged position in the mode of production, should also take into account the interests of other dominant classes and popular interests (at least minimum economic development) into consideration and adopt them into the general interests or ‘common sense’. This will include other dominant groups into hegemonic ‘bloc’ and, thus, will prevent counter-hegemonic movements by these groups, and also minimum economic development will be important to get ‘public consent’.[20]

However, the development of events, in the early years of Russian Federation, did not overlap with above mentioned scenario. During Yeltsin’s presidency sharp reforms were undertaken to “facilitate the construction of a market economy and the reconstruction of the Russian state” which was considered as a failed “shock therapy”.[21] Reforms brought economic crisis, the rate of poverty increased, and a corrupt group of ‘oligarchy’ emerged, who, as a result of privatization of the former Soviet state industries, accumulated tremendous wealth and power. Thus, we observe the emergence of a dominant social force – oligarchy – whose dominance was primarily driven with advantaged position – control of former state industries – in the social relations of production within Russia. Although oligarchy had a political support from Yeltsin government, the interest of other dominant groups and popular interests were not taken into account, which gave rise for opposition groups and popular discontent. Instead of taking measures to get the ‘public consent’ and the ‘consent’ of opposition groups, as Worth finds out, Yeltsin preferred to deal with these issues ‘in an authoritative manner’ or in Gramsci’s words, with the use of ‘coercion’ which cannot be enough to establish ‘hegemony’. Thus we can conclude that Yeltsin had failed to construct a stable hegemonic order, as the mode of production in Russia developed into a ‘barbaric capitalism’ and ‘neoliberal autocracy’.[22]

After succeeding Yeltsin, however, Putin appeared to bring certain changes and take the way of ‘transformismo’.[23] It involved certain concessions to the opposing groups – nationalists and neo-communists – that have appealed to their respective rhetoric. The laws on the structure of the political parties were drastically altered to limit the sheer number and diversity that were competing in elections. Gradual economic growth was sustained and ‘oligarchs’ were deprived of their absolute control of economy. The steps were taken to strengthen the power base at the centre, but, unlike Yeltsin, with far more popular support. However, Worth argues, it may be hasty to suggest that the process of ‘transformismo’ was successfully completed within Russia, although political, economic and cultural changes by Putin had achieved, to some extent, consensus that seemed inconceivable under Yeltsin.[24] The top-down enforcement of policy can only be understood as Putin’s reliance on the elements of ‘Caesarism’ to consolidate the process of ‘transformismo’.

All these developments are important to understand Russia’s relations with other post soviet republics, but before moving to these relations, it should be mentioned that, while highlighting Russia’s domestic issues, the aim is not to argue that they alone determine its external relations. Instead, as Cox argues, none of them should be overemphasized as “all these levels are interrelated”.[25] From this perspective, Russia is also not an exception, where the developments within the state are also influenced by the international factors. For instance, during Yeltsin, the domestic reforms, although unsuccessful, were mainly driven by the goal to integrate Russia into the global economy and support by international institutions such as the IMF and other IFIs was significant. The same might be said about Putin’s presidency, as his “controlled market reform and attracting sustained foreign investment”, Richard Sakwa argues, ‘were deemed necessary for desired WTO membership’. [26]

Post-Soviet ‘World Order’ or Order in Post-Soviet ‘World’: Russia’s Relations with Post-Soviet Republics

Thus, now, moving to Russia’s relations with other republics in post-soviet ‘world’ and to its attempts to (re)establish hegemonic order in this ‘world’ and drawing the parallels with the abovementioned developments within Russia we can see how they are interrelated. If again to refer to the Coxian framework, after being established within Russia, hegemonic order could expand beyond its borders. This, however, was not the case with Russia, as discussed above. The attempts to establish order within the country were unsuccessful, except some stability achieved through authoritative measures. This, as we shall see, also had impact on Russia’s attitudes towards the newly independent republics. Here also authoritative means or, in Gramsci’s terms, ‘coercion’ was the most preferred option to maintain Russian dominance in the region.

Ethnic – Territorial conflicts, for instance, were used as a tool to stop the newly independent republics from escaping Russian influence and integrating into ‘west’ led hegemonic world order. ‘Transnistria Conflict’ [27] in Moldova, ‘Nagorno Karabakh Conflict’ in Azerbaijan (with Armenia), Abkhazia and South Ossetia conflicts in Georgia[28] was used as a means in the “efforts of Russia to maintain its influence and control as the major regional hegemon in the area”. The conflicts, where the role of ‘Russian hand’ was undeniable, created a chaos and conditions to overthrow nationalist-democrat leaders and replace them with ex-communist leaders who were close to Moscow. It began, in 1991-92, from Georgia, where President Zvaid Gamsakhurdia was replaced by former Georgian Communist Party boss (Soviet Foreign Minister) Eduard Shevernadze:

… a phenomenon that came to be referred to as ‘the Georgia Syndrome’. The awful civil war in Tajikistan became the ‘Tajik Variant’ …, while hot summer of 1993 in Baku was called the ‘Azerbaijan Example’. Political wags and post-Sovietologists can now discuss the ‘Moldova Model’, the ‘Crimean Example’ and even the ‘Estonian Experience’ all built on the original Georgian theme.[29]

Goltz continues:

The leitmotif in each case remained disturbingly similar: governments in former Soviet republics that wanted real independence from Moscow were riven by separatist conflicts until the population began to beg for a Soviet-style strong man to restore order.[30]

Another example of the application of coercion to attain dominance might be the military interference, although sometimes under the ‘Peacekeeping Operations’ label, to the above mentioned separatist regions.[31] As Lynch puts, after Soviet collapse, Russia pursued “coercive forward policies and intervened into the so called ‘near abroad’ to protect Russian interests”. For instance, during the Abkhazian rebels against Georgian government, in 1993, the role of Russian military support was crucial and, later, the troops were reformulated as peacekeeping forces.[32]

Here, if to refer to Cox (see 1st section), the use of coercion might be seen as a result of that the ‘weak’ (post-soviet republics) did not ‘accept the prevailing power relations with the ‘strong’ (Russia) as legitimate and wanted to run of its dominance. However, Cox also explains that for the ‘weak’ to find it legitimate the strong should see its mission as ‘hegemonic and not merely dominant dictatorial’. That is to say, Russia should be making ‘concessions that will secure the acquiescence’ of these states ‘in their leadership and should be able to ‘express this leadership in terms of universal or general interests’ of all post-soviet republics, rather than just as serving Russia’s own particular interests.[33]

Russia, however, could meet none of these elements to shift its mission from a ‘dominant dictatorial’ to a ‘hegemonic’ one. Instead, its policy towards the post-soviet republics, which was termed as ‘Near Abroad’ policy, was considered by the “leaders and elites in those republics” as “limitations on the sovereignty or status of the new states”.[34]

A positive step towards building hegemony, if to refer to Cox’s abovementioned understanding of international organizations as a mechanism of hegemony, could be the creation of the regional international organization, encompassing the post soviet republics, the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). The organization could be useful to alter the ‘dominant dictatorial’ perception of Russia by the other states, as it was designed to facilitate “post-Soviet cooperation and integration in political, economic, and security spheres”.[35] For that purpose, it should “reflect orientations favourable to the dominant forces” but at the same time “permit adjustments to be made by subordinated interests”.[36] Nevertheless, by the end of the 1990s many CIS members “convinced they had little voice within it” and “had grown weary of the CIS and suspicious of Russia” and most analysts assessed the organization’s function as a failure.[37] Not only had the organization achieved the aimed (re)integration in the post soviet area, it also could not stop the disintegration process after the collapse of USSR and it was still growing in intensity (Brzezinski and Sullivan, 1997: 106). Dash describes the processes evolving within the post soviet area as:

Even as many countries of Europe unite together in the European union forgetting their national barriers and currencies,, the soviet successor states are on the other hand trying to erect visa and tariff barriers among themselves, build national armies and have often inched on the brink mutual hostility on the basis of ethno-national differences.[38]

After Putin came to power, in parallel to the changes he brought within the state that had characteristics of ‘transformismo’, some positive developments were also observed in Russia’s relations towards CIS countries. The changes targeted the achieving the ‘consent’ rather than continuing the ‘coercive’ means pursued by Yeltsin. A new and multilevel institutional base was developed, in order to prevent further political, economic and military fragmentation in the CIS region. In 2003 the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) was established, consisting of Russia, Belarus, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. Along with traditional military threats, the Charter of the CSTO also was covering the commitment to fight international terrorism and extremism, illegal trade of narcotics, psychotropic substances or arms, organized trans-national crime, and illegal migration.[39] Through these universally acceptable norms and procedures Russia was trying to promote its hegemonic position within CIS region. For instance, later Russia proposed to create the CIS Joint Counter-Terrorist Centre based in Moscow, whose activities were to be headed by the director of FSB (Federal Security Service of Russian Federation).[40] In Economic field, creation of the Single Economic Space (SES) between Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan and Belarus deserves attention. As Secrieru observes, these institutional developments were seen as “means to prevent the centrifugal process among former-Soviet republics and to forge homogeneous military security and economic space under Russian leadership”.[41]

However, it was not always possible for Russia to follow the non-coercive and consensual means to achieve its hegemonic goals. Russia was, still, being considered as a threat and a power that wanted to dominate over them for its own gain rather than as a hegemon pursuing general interests. Considered military and economic projects had a ‘dictatorial dominant’ character in the perceptions of most CIS members. For that reasons Georgia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan and Moldova, refused to join the CSTO and created another organization, GUUAM (initials of country names, changed to GUAM after Uzbekistan withdrew and joined CSTO).[42] SES also was not attractive within CIS states and comprised of few post soviet republics[43] and in further phase of integration Ukraine did not join the Custom Union (between Belarus Russia, Kazakhstan) created in 2010.[44] Thus, as the measures to get the ‘consent’ of CIS states do not give the desired results and the use of ‘coercive’ means stay crucial for the search of dominance. Direct conflicts with Russia and/or conflicts within the post-soviet countries (although political, economic, military, cultural, ethnic or territorial), that also somehow relates to Russia, remain, at least, one of the main, if not the only, reasons why they do not completely integrate into western structures. For instance, Ukraine and Georgia’s application for admission to NATO were refused because, as Russian foreign minister said, Russia did “everything possible to prevent its neighbours, Ukraine and Georgia, being admitted to NATO”.[45]

To conclude, to establish Russian hegemony the use of ‘coercion’ is not enough, but also Russia is not capable to do more to achieve ‘consent’, that is, ‘dominant dictatorial’ character of Russia’s foreign policy is not sufficient, but neither Russia can fulfil ‘hegemonic’ responsibilities. The developments, of this kind, in Russia’s relations with post soviet republics are very consistent with how Kagarlitsky’s describes the developments within Russia:

We [Russia] have not matured sufficiently for socialism, but we cannot live under capitalism. We are incapable of catching up with the West, but neither can we allow ourselves to remain in backwardness. We are not ready for democracy, but we do not want dictatorship.[46]

Conclusion

In the paper I tried to argue that Neo-Gramscian approach, indeed, provides a valid explanation of international relations. Moreover, I have also tried to highlight the advantages of this approach in compare with mainstream IR theories. It included complex account of developments within the states and beyond their borders. For that purpose, I applied Neo-Gramcsian approach to Russia and its relations with post-soviet republics where we observed interplay between ‘social relations’ within Russia, its form of state and, subsequently, its external relations. We observed the impact of economic developments on the formation of ‘social forces’. We observed how these social forces and their relations among each other and with state shape the form of state and how all these reflected in Russia’s attitudes towards former soviet republics.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia wanted to restore the hegemonic order that it enjoyed within USSR. However, for that Russia first needed to establish hegemony within the country, which eventually could not be achieved. This fact also brought to unsuccessful attempts to build hegemonic order between the states in post-soviet world.

Unlike mainstream theories, which would focus, only, on the states themselves, neglecting the role of abovementioned actors, and also on political variables neglecting economic ones, the Neo-Gramcsian approach provided more complex explanation of the considered relations. All these give us a reason to conclude that the Neo-Gramcsian approach can provide a valid explanation of international relations, although through the very complex theoretical lenses.

Comments Off on Russia’s Relations with Post-Soviet Republics: A Neo-Gramscian Approach

Prospects for Energy Independence in Romania: Shale Gas and beyond

October 20th, 2014

By Ariz Husenov.

Romania, historically one of the world’s main energy producers, became a net importer of oil and gas in the 1970s when production started to declined. However, Romania is still luckier than other Central and Eastern European countries in terms of energy dependence. With regards to natural gas supplies, about 75 per cent are produced domestically, and the rest is imported. To compare, all of its neighbours – Ukraine, Moldova, Hungary, Serbia and Bulgaria – are almost completely dependent on imported gas from one source: Russia.

Nevertheless, gas imports remain a crucial element of Romania’s energy security. Although the share of imported gas in total consumption is low at 25 per cent, at least the amount of imported gas is considerably large: about 3.5 billion cubic meters. By comparison, in neighbouring Bulgaria the annual total consumption of gas is around 3 billion cubic meters.

Secondly, the fact that external energy supply is not diversified further threatens energy security. Exactly 98 per cent of gas imports come from Russia. A painful energy crisis will be inevitable if supply is disrupted, whether for political, economic, environmental, technical or any other reasons. There will simply be no alternative sources to substitute the cut-offs. The crisis will hit households and different sectors of economy hard, since natural gas is a main source heating. That was the case in the 2006 and 2009 when disputes between Ukraine and Russia interrupted gas flows to Eastern Europe. Cut-offs seriously jeopardised energy supplies in Romania as well.

Last and not least, Russia accounts for 98 per cent of imports while Romanian-Russia relations remain tense because of clashing interests over Moldova. Romania considers Moldova its historical territory and promotes its European integration, which it thinks will mitigate Russian influence in Moldova and create favourable conditions for the eventual integration of Moldova with Romania. Russia in turn sees Moldova along with other post-Soviet republics as its sphere of influence and creates obstacles to its European path. The main leverages Russia has is its monopolist position on the exports of oil and gas and its capacity to manipulate the Transnistria conflict in Moldova. Hence, while dependence on one source is in itself an undesirable outcome, tense Romanian-Russian relations further aggravate the already difficult situation.

To mitigate the situation and diversify its imports, Romania invested great hopes for the realisation of the Nabucco West gas pipeline project designed to bring gas from Azerbaijan to Romania and other energy dependent countries of the region. On May 20th 2013, the governments of Austria, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Turkey made a joint statement emphasising the importance of the Nabucco project for the Western Balkans and Visegrad countries. Not long afterwards, the heads of those same countries sent letters expressing their support for the project to the President of Azerbaijan Ilham Aliyev. However, expectations muted when on July 28th the Shahdeniz Consortium members involved in the production of gas in Azerbaijan preferred TAP (the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline) over the Nabucco West project. TAP will carry gas to Italy through Greece and Albania, bypassing Romania and the others.

Disappointed with the news, Romania from then on had no choice but to rely on its own. While expressing disappointment, the president accused the European Union of letting the project to fail and demanded compensation for the 23 million euros that Romania spent on the project. He also declared that Romania will not wait on others (implying the EU) to decide anymore and will follow its own path to meet its energy security.

Indeed, the president had the right to say this. Those developments came at a time when new offshore fields were discovered in the Black Sea and the government gave a green light to shale gas explorations. Those developments, the president stated, will make Romania energy independent and perhaps an energy exporter for the first time since the 1970s. Besides, Romania actively develops interconnector infrastructure to integrate into the regional networks. Hence, those three directions – exploration and exploitations of shale gas resources, development of offshore gas fields in the Black Sea and development of the network of interconnectors with neighbouring countries – should lead Romania to energy independence.

To start with shale gas, Romania has one of the biggest reserves in Eastern Europe. According to the estimates of the US Energy Information Administration, Romanian shale gas reserves equal 1.4 trillion cubic meters. In other words, keeping the current consumption levels constant those resources would be enough for 100 years. However, having shale gas resources is one thing, and exploring, exploiting and consumption are another. In short, there is a long way with many obstacles to go before these resources become available for consumption.

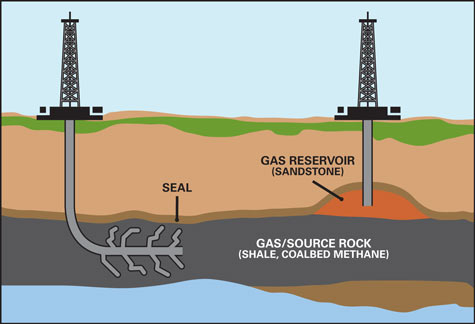

In general, the shale gas issue is a subject of disputes not only in Romania but in other European countries as well. For instance, following long debates, Britain finally waived the restrictions on shale gas production. By contrast, Bulgaria, France, the Czech Republic and the Netherlands have all suspended national shale gas exploration activities. The main objections to shale gas production result from the application of hydraulic fracturing, pumping water and chemicals under high pressure into underground rocks. Critics say it can cause the poisoning of water resources and small earthquakes as a result of tectonic changes. However, energy companies assure that it is not dangerous due to the introduction of the latest technologies and strict safety regulations. As for governments, they have to face the dilemma and delicately calculate the costs and benefits before taking a position. On the one hand, shale gas explorations mean huge investments, employment opportunities, opportunities for cheaper energy due to the growing domestic production and tougher competition and decreased dependence on external sources. On the other, governments should not forget about environmental concerns, not in the least because they can result in public and then political unrest and can harm the image of those in power.

The root of these controversies goes back to 2010, when Romania signed an agreement with Chevron on shale gas exploration in an area of 2 million hectares. However, after only two years the dissemination of information to the public about the alleged negative effects of shale gas production on the environment led to mass protests. The protesters successfully demanded the government to prevent shale gas explorations. The government saw no solution but to ban it. The ongoing political and economic crisis at the time also played a role. In an intense political rivalry, none of the political forces wanted to take responsibility for the controversial shale gas explorations and risk losing voters.

Only after the union of liberal and socialist parties the Social Liberal Union won the parliamentary elections on December 9th 2012 and relative stability established in the country, the government began to reconsider its position on shale gas. Initially, in December when the ban expired, the government did not renew it. Soon after in March 2013, a moratorium on shale gas was waived. Next, in July the government announced plans to attract 10 billion euros in investment and create 50,000 new jobs. The development of shale and offshore gas fields and gold mining projects were among the projects in the plan introduced by the government. But these projects were perceived ambiguously. Thousands poured to the streets and started to protest, claiming that those projects threaten the environment. Although the main concern of the protesters was the development of the Rosia Montana Gold Mining project (and the use of toxic cyanide), protests covered shale gas developments as well.

Since the government lifted the ban on shale gas, Chevron saw no obstacles to announcing its first drilling plans in November 2013 in the small village of Pungesti. The government and Chevron neglected public opinion. Nonetheless, despite attempts in November and later in December, local protesters did not let Chevron bring its facilities for drilling the area. It resulted in clashes and police interventions. Afterwards, the Romanian government and companies clearly understood it is important to engage with local communities before starting explorations. What was done in Romania to this end was very limited, whereas in the United Kingdom, for instance, to promote shale gas developments the government ruled that local councils which allow shale gas development can keep 100 per cent of the business rates they collect from shale gas sites. Consequently, the Romanian government launched initiatives to this end, such as organising meetings and discussions with local communities and considered holding local referendums. However, to gain the public’s trust will not be an easy task, especially taking into account that Romanians’ trust in their government is low. Romania is the third most corrupt country in the EU after Greece and Bulgaria.

By no means, however, should public consent, if achieved, be seen as a good for Romania. It will only pave the way for the first exploration drillings. Poland is a good example to have an idea of how long it can take to prove the volumes of the reserves: 50 exploration wells have been drilled so far and there are plans to drill another 30 wells this year, while a minimum 200 of such wells are needed for a full estimation of the reserves. Hence before reaping the benefits Romania will need to patiently deal with public discontent for the explorations to prove whether there is a commercial volume of reserves and only then, if proved, to wait for the exploitation projects to start, which also will take considerable time.

Meanwhile, Romania is also seeking to develop conventional offshore gas fields discovered in the Black Sea. In February 2012, ExxonMobil and OMV Petrom, the daughter company of Austria’s OMV, jointly declared finding a major gas field, Domino-1. The amount of the deposit, according to initial estimations, is 40-80 billion cubic meters. Annual production is expected to be about 6.5 billion cubic meters. Findings attracted a fair amount of attention in neighbouring countries as well. So far, Bulgaria signed a deal with France’s Total for the exploration and development of the Khan Asparuh block. Ukraine planned to sign an official agreement with ExxonMobil at the end of 2013. However, due to the political turmoil after refusing to sign Association Agreement with the EU it become impossible for indefinite period.

Hypothetically, if the volumes will not be far from what is expected and desired, the impact of them will go beyond Romania and change the energy map of the whole region. So far, however, there is modest evidence of this. Expectations are mainly based on optimistic scenarios. The news release by the companies exploring the fields in the Black Sea mainly contains forward-looking statements such as “anticipates,” “estimates,” and similar references to future periods. Besides, initially the production in Domine-1 was expected to start in 2015-17. It became clear that first production is estimated at the earliest at the end of this decade. Back then, the plan was to start drilling for exploration and not production towards the end of 2013. However, there is still no official news from either the companies or the government.

In the meantime, while potential resources are still to be delineated and properly appraised, Romania focused on developing interconnectors with neighbouring countries to integrate with the regional gas market. The construction of the interconnector Giurgiu-Ruse between Romania and Bulgaria started in October 2009; completion was scheduled for January 1st 2013. However, it is still not completed and a new deadline was not yet declared. The pipeline will have a capacity of 1.5 billion cubic meters and a total length of 25 km (8.4 km in Romania and 16.6 km in Bulgaria). Transgaz and Bulgartransgaz, companies from Romania and Bulgaria, respectively, contributed €14.9 Million while €8.9 million was co-financed by the EU.

The construction of the interconnector Ungheni-Iasi between Romania and Moldova started in August 2013 with a ground-breaking ceremony during Romanian Prime Minister Victor Ponta’s visit to Moldova. Along with energy concerns, Romania considers this project important to integrating Moldova as well. The Romanian government has committed to assist Moldova with €9 million for the project. The total cost is estimated at €26.5 million, of which €7 million is funded by the EU. On January 8th 2014, Romania’s National Agency for Mineral Resources reported in a note released that “the consortium has concluded the main work in Romania”. Overall, 32.19 km of the 42.49 km pipeline is in Romania and 10.5 km is in Moldova.

Completed in 2010, the Arad-Szeged interconnector between Romania and Hungary operates in one direction to import gas from Hungary. As for Serbia, the gas interconnection Mokrin-Arad that is to link it with Romania is in a conceptual stage, although it was first proposed years ago.

The completion of these projects will make Romania part of the integrated gas transport system which is important for security since it provides diversified routes of imports. However, two factors, although not eliminating, are seriously limiting the importance of those interconnectors. First, none of Romania’s neighbours is a producer and, as stated in the beginning of this article, all are completely dependent on Russian imports. As follows, although the routes of imports will be diversified, the source of imported gas will stay the same. Secondly, the capacities of interconnectors are, as usual, limited for a large volumes of imports. Nevertheless, those interconnectors can be crucial for security when struggling with supply cuts during short period crisis and are mainly designed to for that purpose.

Comments Off on Prospects for Energy Independence in Romania: Shale Gas and beyond