September 20th, 2016

=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=-=

It’s only when the tide goes out that you learn who has been swimming naked.

— Warren Buffett, credit Old School Value

When I was 29, nearly half a life ago, Donald Trump was a struggling real estate developer. In 1990, I was still trying to develop my own views of the economy and finance. But one day heading home from work at AIG, I was listening to the business report on the radio, and I heard the announcer say that Donald Trump had said that he would be “the king of cash.” My tart comment was, “Yeah, right.”

At that point in time, I knew that a lot of different entities were in need of financing. Though the stock market had come back from the panic of 1987, many entities had overborrowed to buy commercial real estate. The major insurance companies of that period were deeply at fault in this as well, largely driven by the need to issue 5-year Guaranteed Investment Contracts [GICs] to rapidly growing stable value funds of defined contribution plans. Outside of some curmudgeons in commercial mortgage lending departments, few recognized that writing 5-year mortgages with low principal amortization rates against long-lived commercial properties was a recipe for disaster. This was especially true as lending yield spreads grew tighter and tighter.

(Aside: the real estate area of Provident Mutual avoided most of the troubles, as they sold their building that they built seven years earlier for twice what they paid to a larger competitor. They also focused their mortgage lending on small, ugly, economically necessary properties, and not large trophy properties. They were unsung heroes of the company, and their reward was elimination eight years later as a “cost saving move.” At a later point in time, I talked with the lending group at Stancorp, which had a similar philosophy, and expressed admiration for the commercial mortgage group at Provident Mutual… Stancorp saw the strength in the idea, and still follows it today as the subsidiary of a Japanese firm. But I digress…)

Many of the insurance companies making the marginal commercial mortgage loans had come to AIG seeking emergency financing. My boss at AIG got wind of the fact that I was looking elsewhere for work, and subtly regaled me of the tales of woe at many of the insurance companies with these lending issues, including one at which I had recently interviewed. (That was too coincidental for me not to note, particularly as a colleague in another division asked me how the search was going. All this from one stray comment to an actuary I met coming back from the interview…)

Back to the main topic: good investing and business rely on the concept of a margin of safety. There will be problems in any business plan. Who has enough wherewithal to overcome those challenges? Plans where everything has to go right in order to succeed will most likely fail.

With Trump back in 1990, the goal was admirable — become liquid in order to purchase properties that were now at bargain prices. As was said in the Wall Street Journal back in April of 1990, the article started:

In a two-hour interview, Mr. Trump explained that he is raising cash today so he can scoop up bargains in a year or two, after the real estate market shakes out. Such an approach worked for him a decade ago when he bet big that New York City’s economy would rebound, and developed the Trump Tower, Grand Hyatt and other projects.

“What I want to do is go and bargain hunt,” he said. “I want to be king of cash.”

That’s where Trump said it first. After that he received many questions from reporters and creditors, because his businesses were heavily indebted, and property values were deflated, including the properties that he owned. Who wouldn’t want to be the “king of cash” then? But to be in that position would mean having sold something when times were good, then sitting on the cash. Not only is that not in Trump’s nature, it is not in the nature of most to do that. During good times, the extra cash that Buffett keeps on hand looks stupid.

Trump did not get out of the mess by raising cash, but by working out a deal with his creditors in bankruptcy. Give Trump credit, he had convinced most of his creditors that they were better off continuing to finance him rather than foreclose, because the Trump name made the properties more valuable. Had the creditors called his bluff, Trump would have lost a lot, possibly to the point where we wouldn’t be hearing much about him today.

Trump escaped, but most other debtors don’t get the same treatment Trump did. The only way to survive in a credit crunch is plan ahead by getting adequate long-term financing (equity and long-term debt), and keep a “war kitty” of cash on the side.

During 2002, I had the chance to test this as a bond manager. With the accounting disasters at mid-year, on July 27th, two of my best brokers called me and said, “The market is offered without bid. We’ve never seen it this bad. What do you want to do?” I kept a supply of liquidity on hand for situations like this, so with the S&P falling, and the VIX over 50, I put out a series of lowball bids for BBB assets that our analysts liked. By noon, I had used up all of my liquidity, but the market was turning. On October 9th, the same thing happened, but this time I had a larger war chest, and made more bids, with largely the same result.

That’s tough to do, and my client pushed me on the “extra cash sitting around.” After all, times are good, there is business to be done, and we could use the additional interest to make the estimates next quarter.

To give another example, we have the visionary businessman Elon Musk facing a cash crunch at Tesla and SolarCity. Leave aside for a moment his efforts to merge the two firms when stockholders tend to prefer “pure play” firms to conglomerates — it’s interesting to look at how two “growth companies” are facing a challenge raising funds at a time when the stock market is near all time highs.

Both Tesla and Solar City are needy companies when it comes to financing. They need a lot of capital to grow their operations before the day comes when they are both profitable and cash flow from operations is positive. But, so did a lot of dot-com companies in 1998-2000, of which a small number exist to this day. Elon Musk is in a better position in that presently he can dilute issue shares of Tesla to finance matters, as well as buy 80% of the Solar City bond issue. But it feels weird to have to finance something in less than a public way.

There are other calls on cash in the markets today — many companies are increasing dividends and buying back stock. Some are using debt to facilitate this. I look at the major oil companies and they all seem to be levering up, which is unusual given the recent trajectory of crude oil prices.

We are in the fourth phase of the credit cycle now — borrowing is growing, and profits aren’t. There’s no rule that says we have to go through a bear market in credit before that happens, but that is the ordinary way that excesses get purged.

That is why I am telling you to pull back on risk, and review your portfolio for companies that need financing in the next three years or they will croak. If they don’t self finance, be wary. When things are bad only cash flow can validate an asset, not hopes of future growth.

With that, I close this article with a poem that I saw as a graduate student outside the door of the professor for whom I was a teaching assistant when I first came to UC-Davis. I did not know that is was out on the web until today. It deserves to be a classic:

Once upon a midnight dreary as I pondered weak and weary

Over many a quaint and curious volume of accounting lore,

Seeking gimmicks (without scruple) to squeeze through

Some new tax loophole,

Suddenly I heard a knock upon my door,

Only this, and nothing more.

Then I felt a queasy tingling and I heard the cash a-jingling

As a fearsome banker entered whom I’d often seen before.

His face was money-green and in his eyes there could be seen

Dollar-signs that seemed to glitter as he reckoned up the score.

“Cash flow,” the banker said, and nothing more.

I had always thought it fine to show a jet black bottom line.

But the banker sounded a resounding, “No.

Your receivables are high, mounting upward toward the sky;

Write-offs loom. What matters is cash flow.”

He repeated, “Watch cash flow.”

Then I tried to tell the story of our lovely inventory

Which, though large, is full of most delightful stuff.

But the banker saw its growth, and with a might oath

He waved his arms and shouted, “Stop! Enough!

Pay the interest, and don’t give me any guff!”

Next I looked for noncash items which could add ad infinitum

To replace the ever-outward flow of cash,

But to keep my statement black I’d held depreciation back,

And my banker said that I’d done something rash.

He quivered, and his teeth began to gnash.

When I asked him for a loan, he responded, with a groan,

That the interest rate would be just prime plus eight,

And to guarantee my purity he’d insist on some security—

All my assets plus the scalp upon my pate.

Only this, a standard rate.

Though my bottom line is black, I am flat upon my back,

My cash flows out and customers pay slow.

The growth of my receivables is almost unbelievable:

The result is certain—unremitting woe!

And I hear the banker utter an ominous low mutter,

“Watch cash flow.”

Herbert S. Bailey, Jr.

Source: The January 13, 1975, issue of Publishers Weekly, Published by R. R. Bowker, a Xerox company. Copyright 1975 by the Xerox Corporation. Credit also to aridni.com.

Comments Off on The Cash Will Prove Itself

March 16th, 2015

Brian Lund recently put up a post called 5 Reasons You Deserve to Lose Every Penny in the Stock Market. Though I don’t endorse everything in his article, I think it is worth a read. I’m going to tackle the same question from a broader perspective, and write a different article. As we often say, “It takes two to make a market,” so feel free to compare our views.

I have one dozen reasons, many of which are related. I do them separately, because I think it reveals more than grouping them into fewer categories. Here we go:

1) Arrive at the wrong time

When does the average person show up to invest? Is it when assets are cheap or expensive?

The average person shows up when there has been a lot of news about how well an asset class has been doing. It could be stocks, housing, or any well-known asset. Typically the media trumpets the wisdom of those that previously invested, and suggests that there is more money to be made.

It can get as ridiculous as articles that suggest that everyone could be rich if they just bought the favored asset. Think for a moment. If holding the favored asset conferred wealth, why should anyone sell it to you? Homebuilders would hang onto their inventories. Companies would not go public — they would hang onto their own stock and not sell it to you.

I am reminded of some of my cousins who decided to plow money into dot-com stocks in late 1999. Did they get to the party early? No, late. Very late. And so it is with most people who think there is easy money to be made in markets — they get to the party after stock prices have been bid up. They put in the top.

2) Leave at the wrong time

This is the flip side of point 1. If I had a dollar for every time someone said to me in 1987, 2002 or 2009 “I am never touching stocks ever again,” I could buy a very nice dinner for my wife and me. Average people sell in disappointment thinking that they are protecting the value of their assets. In reality, they lock in a large loss.

There’s a saying that the right trade is the one that hurts the most. Giving into greed or fear is emotionally satisfying. Resisting trends and losing some money in the short run is more difficult to do, even if the trade ultimately ends up being profitable. Maintaining exposure to stocks at all times means you ride a roller coaster, but it also means that you earn the long-term returns that accrue to stocks, which market timers rarely do.

You can read some of my older pieces on how investors earn less on average than buy-and-hold investors do. Here’s one on how investors in the S&P 500 ETF [SPY], trail buy-and-hold returns by 7%/year. Ouch! That comes from buying and selling at the wrong times. ETFs may lower expenses, but they also make it easy for people to trade at the wrong times.

3) Chase the hot sector/industry

The lure of easy money brings out the worst in people. Whether it is tech stocks in 1987, dot-coms in 1999, or housing-related assets in 2007, there will always be people who think that the current industry fad will be a one-way ticket to riches. There is psychological satisfaction to be had by buying what is popular. Everyone wants to be one of the “cool kids.” It’s a pity that that is not a good way to make money. That brings up point 4:

4) Ignore Valuations

The returns you get are a product of the difference in the entry and exit valuations, and the change in the value of the factor used to measure valuation, whether that is earnings, cash flow from operations, EBITDA, free cash flow, sales, book, etc. Buying cheap aids overall returns if you have the correct estimate of future value.

This is more than a stock market idea — it applies to private equity, and the purchase of capital assets in a business. The cheaper you can source an asset, the better the ultimate return.

Ignoring valuations is most common with hot sectors or industries, and with growth stocks. The more you pay for the future, the harder it is to earn a strong return as the stock hopefully grows into the valuation.

5) Not think like a businessman, or treat it like a business

Investing should involve asking questions about whether the economic decisions are being made largely right by those that manage the company or debts in question. This is not knowledge that everyone has immediately, but it develops with experience. Thus you start by analyzing business situations that you do understand, while expanding your knowledge of new areas near your existing knowledge.

There is always more to learn, and a good investor is typically a lifelong learner. You’d be surprised how concepts in one industry or market get mirrored in other industries, but with different names. One from my experience: Asset managers, actuaries and bankers often do the same things, or close to the same things, but the terminology differs. Or, there are different ways of enhancing credit quality in different industries. Understanding different perspectives enriches your understanding of business. The end goal is to be able to think like an intelligent business manager who understands investing, so that you can say along with Buffett:

I am a better investor because I am a businessman, and a better businessman because I am an investor.

(Note: this often gets misquoted because Forbes got mixed up at some point, where they think it is: I am a better investor because I am a businessman, and a better businessman because I am no investor.) Good investment knowledge feeds on itself. Little of it is difficult, but learn and learnuntil you can ask competent questions about investing.

After all, you are investing money. Should that be easy and require no learning? If so, any fool could do it, but my experience is that those who don’t learn in advance of investing tend to get fleeced.

6) Not diversify enough

The main objective here is that you need to only invest what you can afford to lose. The main reason for this is that you have to be calm and rational in all the decisions you make. If you need the money for another purpose aside from investing, you won’t be capable of making those decisions well if in a bear market you find yourself forced to sell in order to protect what you have.

But this applies to risky assets as well. Diversification is inverse to knowledge. The more you genuinely know about an investment, the larger your positions can be. That said I make mistakes, as other people do. How much of a loss can you take on an individual investment before you feel crippled, and lose confidence in your abilities.

In the 25+ years I have been investing, I have taken significant losses about ten times. I felt really stupid after each one. But if you take my ten best investments over that same period, they pay for all of the losses I have ever had, leaving the smaller gains as my total gains. As a result, my losses never inhibited me from continuing in investing; they were just a part of the price of getting the gains.

Temporary Conclusion

I have six more to go, and since this article is already too long, they will have to go in part 2. For now, remember the main points are to structure your investing affairs so that you can think rationally and analyze business opportunities without panic or greed interfering.

Comments Off on Part 1: One dozen reasons why the average person underperforms in investing

August 19th, 2014

By David Merkel.

A reader wrote to me and said:

A reader wrote to me and said:

I’m sure a lot of people have already told you but I want to tell you anyway: Your blog is awesome! I came across The Aleph Blog a couple of months ago and I’m very impressed with your content. I particularly like that 4-part article on Using Investment Advice. I am in the financial industry myself and it makes me wish I came up with the kind of ideas that you have on your blog. Awesome stuff!

Keep up the good work,

Many thanks to the reader, and if you want to read that series, it is located here. But when I considered what he wrote to me, it made me think, “Why do we have to tell people how to think about investment advice?”

Then it hit me: because people are looking for easy tips to execute. After all, when I wrote the 4-piece series, I had listening to Jim Cramer in mind. The “tip culture” of inexperienced investors don’t want to learn the ideas behind investing, but just want someone to say, “Buy this.” There is little if any guarantee that the same pundit will ever update his opinion.

We see this on the web, in magazines, newsletters, newspapers, etc. On rare occasion, I will print one out, and add it to my “delayed research stack” which means I will look at it in 1-3 months. I just did my quarterly clean-out a few days ago — anything I add to the stack now will wait until November.

But why read articles like, “Ten Undervalued Large Cap Stocks with Growth Potential,” “Nine Stocks to Buy and Hold Forever,” “Eight Stocks that are Taking Off, Don’t Miss Out,” “Seven Hidden Gens Among Small Caps,” “Six Stocks for Income and Growth,” “Five Energy Stocks that are Poised to Surge,” Four Titanic Stocks that Every Investor Should Own,” “Three Turnaround Stocks with Potential for Large Capital Gains,” “Two Stocks with Breakthrough Technologies,” and “The One Stock that You Should Own for the Next Decade.”

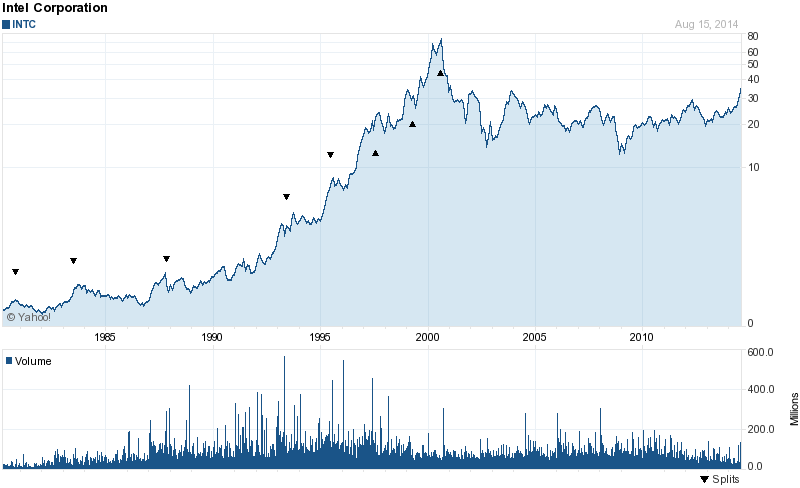

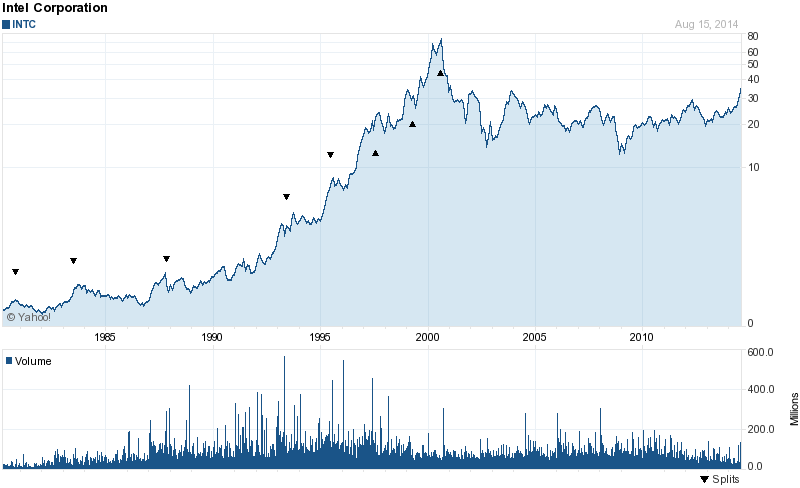

Now, I made those titles up, though the last one was based off a Smart Money article on Intel in late 1999 which came very close to top-ticking the market. As you can see, Intel still hasn’t made it back to the tech bubble peak.

As I Googled phrases like, “Ten Best Stocks,” it was fascinating to see the range of pitches employed:

- Appeals to Buffett (that never gets old)

- Best stocks for this year

- Favorite stocks of an author, manager or publication

- With high dividends

- With a low price

- In emerging markets

- That won’t lose money

- That our patented investment screener spat out

- For the rest of your life

- Etc.

I know that I could get a lot more readers with list articles that tout stocks. I don’t do it because most of the articles that you read like that are bogus. [I also don’t want the inevitable scad of complaints that come with the territory.) So why do such articles draw readers?

People would rather have false certainty than live in the reality that choosing good investments is difficult. Even very good investors hit rough patches where they do not outperform. Also, people aren’t comfortable with uncertain horizons for realizing value in investments — article tout holding forever, ten years, one year, but rarely 3-5 years or a market cycle.

The truth is, you can’t tell when a stock will perform, but when it does perform, the results will be lumpy. The performance of a stock is rarely smooth. During times when the success or failure of a stock idea is realized, the moves are often violent.

Now remember, those who write such articles are looking for media revenue — such articles are sensational, and pander to the desire for easy money. But where are the articles telling you to sell ten stocks now? (Yes, I know there are some, but they are not so common.) Or, where are follow up pieces indicating how well prior picks have done, and whether one should sell, hold, or buy more now?

My main point is this: good amateur investing is like having a part-time job. A part-time job, well, takes time. Weigh that against other priorities in your life — family, friends, church, public service, fun, etc. You may not want a part-time job, and so you can index your investments, or outsource them to a trusted advisor, who hopefully digs up his own ideas, and does not have a consensus, index-like portfolio (If he does, why not index?)

So, avoid tips if you can. If you can’t, develop a research discipline, or set them aside like I do, and revisit them when the original reason for buying it is forgotten, and you must evaluate for yourself now. The investment that you do not understand why you bought it, you will never know when it is the right time to sell it.

Either learn to evaluate investments on your own, or index your investments, or find a good investment advisor. But don’t think that you will do well off of tips.

Comments Off on The Tip Culture in Amateur Investing

July 5th, 2014

By David Merkel.

My comments this evening stem from a Bloomberg.com article entitled Bond Market Has $900 Billion Mom-and-Pop Problem When Rates Rise. A few excerpts with my comments:

It’s never been easier for individuals to enter some of the most esoteric debt markets. Wall Street’s biggest firms are worried that it’ll be just as simple for them to leave.

Investors have piled more than $900 billion into taxable bond funds since the 2008 financial crisis, buying stock-like shares of mutual and exchange-traded funds to gain access to infrequently-traded markets. This flood of cash has helped cause prices to surge and yields to plunge.

Once bonds are issued, they are issued. What changes is the perception of market players as they evaluate where they will get the best returns relative expected future yields, defaults, etc.

Regarding ETFs, yes, ETFs grow in bull markets because it pays to create new units. They will shrink in bear markets, because it will pay to dissolve units. That said when ETF units are dissolved, the bonds formerly in the ETF don’t disappear — someone else holds them.

But in a crisis, there is no desire to exchange existing cash for new bonds that have not been issued yet. Issuance plummets as yields rise and prices fall for risky debt. The opposite often happens with the safest debt. New money seeks safety amid the panic.

Last week, Fed Chair Janet Yellen said she didn’t see more than a moderate level of risk to financial stability from leverage or the ballooning volumes of debt. Even though it may be concerning that Bank of America Merrill Lynch index data shows yields on junk bonds have plunged to 5.6 percent, the lowest ever and 3.4 percentage points below the decade-long average, the outlook for defaults does look pretty good.

Moody’s Investors Service predicts the global speculative-grade default rate will decline to 2.1 percent at year-end from 2.3 percent in May. Both are less than half the rate’s historical average of 4.7 percent.

Janet Yellen would not know financial risk even if Satan himself showed up on her doorstep offering to sell private subprime asset-backed securities for a yield of Treasuries plus 2%. I exaggerate, but yields on high-yield bonds are at an all-time low:

Could spreads grind tighter? Maybe, we are at 3.35% now. The record on the BofA ML HY Master II is 2.41% back in mid-2007, when interest rates were much higher, and the credit frenzy was astounding.

But when overall rates are higher, investors are willing to take spread lower. There is an intrinsic unwillingness for both rates and spreads to be at their lowest at the same time. That has not happened historically, though admittedly, the data is sparse. Spread data began in the ’90s, and yield data in a detailed way in the ’80s. The Moody’s investment grade series go further back, but those are very special series of long bonds, and may not represent reality for modern markets.

Also, with default rates, it is not wise to think of them in terms of averages. Defaults are either cascading or absent, the rating agencies, most economists and analysts do not call the turning points well. The transition from “no risk at all” in mid-2007 to mega-risk 15 months later was very quick. A few bears called it, but few bears called it shifting their view in 2007 – most had been calling it for a few years.

The tough thing is knowing when too much debt has built up versus ability to service it, and have all short-term ways to issue yet a little more debt been exhausted? Consider the warning signs ignored from mid-2007 to the failure of Lehman Brothers:

- Shanghai market takes a whack (okay, early 2007)

- [Structured Investment Vehicles] SIVs fall apart.

- Quant hedge funds have a mini meltdown

- Subprime MBS begins its meltdown

- Bear Stearns is bought out by JP Morgan under stress

- Auction-rate preferred securities market fails.

- And there was more, but it eludes me now…

Do we have the same amount of tomfoolery in the credit markets today? That’s a hard question to answer. Outstanding derivatives usage is high, but I haven’t seen egregious behavior. The Fed is the leader in tomfoolery, engaging in QE, and creating lots of bank reserves, no telling what they will do if the economy finally heats up and banks want to lend to private parties with abandon.

That concern is also revealed in BlackRock Inc.’s pitch in a paper published last month that regulators should consider redemption restrictions for some bond mutual funds, including extra fees for large redeemers.

A year ago, bond funds suffered record withdrawals amid hysteria about a sudden increase in benchmark yields. A 0.8 percentage point rise in the 10-year Treasury yield in May and June last year spurred a sell-off that caused $248 billion of market value losses on the Bank of America Merrill Lynch U.S. Corporate and High Yield Index.

Of course, yields on 10-year Treasuries (USGG10YR) have since fallen to 2.6 percent from 3 percent at the end of December and company bonds have resumed their rally. Analysts are worrying about what happens when the gift of easy money goes away for good.

With demand for credit still weak, it is more likely that rates go lower for now. That makes a statement for the next few months, not the next year. The ending of QE and future rising fed funds rate is already reflected in current yields. Bloomberg.com must be breaking in new writers, because the end of Fed easing is already expected by the market as a whole. Deviations from that will affect the market. But if the economy remains weak, and lending to businesses stays punk, then rates can go lower for some time, until private lending starts in earnest.

Summary

- Is too much credit risk being taken? Probably. Spreads are low, and yields are record low.

- Is a credit crisis near? Wait a year, then ask again.

- Typically, most people are surprised when credit turns negative, so if you have questions, be cautious.

- Does the end of QE mean higher long rates? Not necessarily, but watch bank lending and inflation. More of either of those could drive rates higher.

Comments Off on A Few Notes on Bonds

May 5th, 2014

By David Merkel.

| March 2014 |

April 2014 |

Comments |

| Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in Januaryindicates that growth in economic activity slowed during the winter months, in part reflecting adverse weather conditions. |

Information received since the Federal Open Market Committee met in Marchindicates that growth in economic activity has picked up recently, after having slowed sharply during the winter in part because of adverse weather conditions. |

Weather is always a weak reason for a bad result. You almost never see anyone claim good weather boosted results.

Didn’t they see today’s weak GDP report? |

| Labor market indicators were mixed but on balance showed further improvement. The unemployment rate, however, remains elevated. |

Labor market indicators were mixed but on balance showed further improvement. The unemployment rate, however, remains elevated. |

No significant change. What improvement? Note: this is the one remaining place where they mention the “unemployment rate.” Shh. |

| Household spending and business fixed investment continued to advance, while the recovery in the housing sector remained slow. |

Household spending appears to be rising more quickly. Business fixed investment edged down, while the recovery in the housing sector remained slow. |

Shades household spending down, lowers their view on business fixed investment. |

| Fiscal policy is restraining economic growth, although the extent of restraint is diminishing. |

Fiscal policy is restraining economic growth, although the extent of restraint is diminishing. |

No change. Funny that they don’t call their tapering a “restraint.” |

| Inflation has been running below the Committee’s longer-run objective, but longer-term inflation expectations have remained stable. |

Inflation has been running below the Committee’s longer-run objective, but longer-term inflation expectations have remained stable. |

No change. TIPS are showing slightly lower inflation expectations since the last meeting. 5y forward 5y inflation implied from TIPS is near 2.41%, up 0.15% from March. |

| Consistent with its statutory mandate, the Committee seeks to foster maximum employment and price stability. |

Consistent with its statutory mandate, the Committee seeks to foster maximum employment and price stability. |

No change. Any time they mention the “statutory mandate,” it is to excuse bad policy. |

| The Committee expects that, with appropriate policy accommodation, economic activity will expand at a moderate pace and labor market conditions will continue to improve gradually, moving toward those the Committee judges consistent with its dual mandate. |

The Committee expects that, with appropriate policy accommodation, economic activity will expand at a moderate pace and labor market conditions will continue to improve gradually, moving toward those the Committee judges consistent with its dual mandate. |

No change. |

| The Committee sees the risks to the outlook for the economy and the labor market as nearly balanced. |

The Committee sees the risks to the outlook for the economy and the labor market as nearly balanced. |

No change. |

| The Committee recognizes that inflation persistently below its 2 percent objective could pose risks to economic performance, and it is monitoring inflation developments carefully for evidence that inflation will move back toward its objective over the medium term. |

The Committee recognizes that inflation persistently below its 2 percent objective could pose risks to economic performance, and it is monitoring inflation developments carefully for evidence that inflation will move back toward its objective over the medium term. |

No change. CPI is at 1.5% now, yoy. |

| The Committee currently judges that there is sufficient underlying strength in the broader economy to support ongoing improvement in labor market conditions. |

The Committee currently judges that there is sufficient underlying strength in the broader economy to support ongoing improvement in labor market conditions. |

No change. |

| In light of the cumulative progress toward maximum employment and the improvement in the outlook for labor market conditions since the inception of the current asset purchase program, the Committee decided to make a further measured reduction in the pace of its asset purchases. Beginning in April, the Committee will add to its holdings of agency mortgage-backed securities at a pace of $25 billion per month rather than $30 billion per month, and will add to its holdings of longer-term Treasury securities at a pace of $30 billion per month rather than $35 billion per month. |

In light of the cumulative progress toward maximum employment and the improvement in the outlook for labor market conditions since the inception of the current asset purchase program, the Committee decided to make a further measured reduction in the pace of its asset purchases. Beginning in May, the Committee will add to its holdings of agency mortgage-backed securities at a pace of $20 billion per month rather than $25 billion per month, and will add to its holdings of longer-term Treasury securities at a pace of $25 billion per month rather than $30 billion per month. |

Reduces the purchase rate by $5 billion each on Treasuries and MBS. No big deal.

|

| The Committee is maintaining its existing policy of reinvesting principal payments from its holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in agency mortgage-backed securities and of rolling over maturing Treasury securities at auction. |

The Committee is maintaining its existing policy of reinvesting principal payments from its holdings of agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities in agency mortgage-backed securities and of rolling over maturing Treasury securities at auction. |

No change |

| The Committee’s sizable and still-increasing holdings of longer-term securities should maintain downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, support mortgage markets, and help to make broader financial conditions more accommodative, which in turn should promote a stronger economic recovery and help to ensure that inflation, over time, is at the rate most consistent with the Committee’s dual mandate. |

The Committee’s sizable and still-increasing holdings of longer-term securities should maintain downward pressure on longer-term interest rates, support mortgage markets, and help to make broader financial conditions more accommodative, which in turn should promote a stronger economic recovery and help to ensure that inflation, over time, is at the rate most consistent with the Committee’s dual mandate. |

No change. But it has almost no impact on interest rates on the long end, which are rallying into a weakening global economy. |

| The Committee will closely monitor incoming information on economic and financial developments in coming months and will continue its purchases of Treasury and agency mortgage-backed securities, and employ its other policy tools as appropriate, until the outlook for the labor market has improved substantially in a context of price stability. |

The Committee will closely monitor incoming information on economic and financial developments in coming months and will continue its purchases of Treasury and agency mortgage-backed securities, and employ its other policy tools as appropriate, until the outlook for the labor market has improved substantially in a context of price stability. |

No change. Useless paragraph. |

| If incoming information broadly supports the Committee’s expectation of ongoing improvement in labor market conditions and inflation moving back toward its longer-run objective, the Committee will likely reduce the pace of asset purchases in further measured steps at future meetings. |

If incoming information broadly supports the Committee’s expectation of ongoing improvement in labor market conditions and inflation moving back toward its longer-run objective, the Committee will likely reduce the pace of asset purchases in further measured steps at future meetings. |

No change. Says that purchases will likely continue to decline if the economy continues to improve. |

| However, asset purchases are not on a preset course, and the Committee’s decisions about their pace will remain contingent on the Committee’s outlook for the labor market and inflation as well as its assessment of the likely efficacy and costs of such purchases. |

However, asset purchases are not on a preset course, and the Committee’s decisions about their pace will remain contingent on the Committee’s outlook for the labor market and inflation as well as its assessment of the likely efficacy and costs of such purchases. |

No change. |

| To support continued progress toward maximum employment and price stability, the Committee today reaffirmed its view that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy remains appropriate. |

To support continued progress toward maximum employment and price stability, the Committee today reaffirmed its view that a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy remains appropriate. |

No change. |

| In determining how long to maintain the current 0 to 1/4 percent target range for the federal funds rate, the Committee will assess progress–both realized and expected–toward its objectives of maximum employment and 2 percent inflation. This assessment will take into account a wide range of information, including measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial developments. |

In determining how long to maintain the current 0 to 1/4 percent target range for the federal funds rate, the Committee will assess progress–both realized and expected–toward its objectives of maximum employment and 2 percent inflation. This assessment will take into account a wide range of information, including measures of labor market conditions, indicators of inflation pressures and inflation expectations, and readings on financial developments. |

Monetary policy is like jazz; we make it up as we go. Also note that progress can be expected progress – presumably that means looking at the change in forward expectations for inflation, etc. |

| The Committee continues to anticipate, based on its assessment of these factors, that it likely will be appropriate to maintain the current target range for the federal funds rate for a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends, especially if projected inflation continues to run below the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal, and provided that longer-term inflation expectations remain well anchored. |

The Committee continues to anticipate, based on its assessment of these factors, that it likely will be appropriate to maintain the current target range for the federal funds rate for a considerable time after the asset purchase program ends, especially if projected inflation continues to run below the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal, and provided that longer-term inflation expectations remain well anchored. |

No change. Its standards for raising Fed funds are arbitrary. |

| When the Committee decides to begin to remove policy accommodation, it will take a balanced approach consistent with its longer-run goals of maximum employment and inflation of 2 percent. |

When the Committee decides to begin to remove policy accommodation, it will take a balanced approach consistent with its longer-run goals of maximum employment and inflation of 2 percent. |

No change. |

| The Committee currently anticipates that, even after employment and inflation are near mandate-consistent levels, economic conditions may, for some time, warrant keeping the target federal funds rate below levels the Committee views as normal in the longer run. |

The Committee currently anticipates that, even after employment and inflation are near mandate-consistent levels, economic conditions may, for some time, warrant keeping the target federal funds rate below levels the Committee views as normal in the longer run. |

No change. |

| With the unemployment rate nearing 6-1/2 percent, the Committee has updated its forward guidance. The change in the Committee’s guidance does not indicate any change in the Committee’s policy intentions as set forth in its recent statements. |

|

That sentence lasted only one month. Note that the phrase “unemployment rate” is close to being banned by the FOMC. The dual mandate is not so dual, at least in the old sense. |

| Voting for the FOMC monetary policy action were: Janet L. Yellen, Chair; William C. Dudley, Vice Chairman; Richard W. Fisher; Sandra Pianalto; Charles I. Plosser; Jerome H. Powell; Jeremy C. Stein; and Daniel K. Tarullo.

|

Voting for the FOMC monetary policy action were: Janet L. Yellen, Chair; William C. Dudley, Vice Chairman; Richard W. Fisher; Narayana Kocherlakota; Sandra Pianalto; Charles I. Plosser; Jerome H. Powell; Jeremy C. Stein; and Daniel K. Tarullo. |

Kocherlakota rejoins the majority, even with no change to the “fifth paragraph” of the March statement. |

| Voting against the action was Narayana Kocherlakota, who supported the sixth paragraph, but believed the fifth paragraph weakens the credibility of the Committee’s commitment to return inflation to the 2 percent target from below and fosters policy uncertainty that hinders economic activity. |

|

Thus ends the lamest vote against an FOMC decision that I have ever seen. The differences between the last statement’s fifth and sixth paragraphs were minuscule. |

Comments

- Small $10 B/month taper. Equities and long bonds both rise. Commodity prices fall. The FOMC says that any future change to policy is contingent on almost everything.

- They shaded household spending down, and lowered their view on business fixed investment. Don’t know they keep an optimistic view of GDP growth, especially amid falling monetary velocity.

- At least they are abandoning the unemployment rate as their measure of labor conditions.

- They missed a real opportunity to simplify the statement. More words obfuscate, they do not clarify.

- In the past I have said, “When [holding down longer-term rates on the highest-quality debt] doesn’t work, what will they do? I have to imagine that they are wondering whether QE works at all, given the recent rise and fall in long rates. The Fed is playing with forces bigger than themselves, and it isn’t dawning on them yet.

- The key variables on Fed Policy are capacity utilization, unemployment, inflation trends, and inflation expectations. As a result, the FOMC ain’t moving rates up, absent increases in employment, or a US Dollar crisis. Labor employment is the key metric.

- GDP growth is not improving much if at all, and much of the unemployment rate improvement comes more from discouraged workers, and part-time workers.

Comments Off on Redacted version of the April 2014 FOMC Statement

November 5th, 2013

By David Merkel.

This article was originally going to be titled, “Dying Cities, Dying States, Dying….” I thought that would be correct but too pointy. The key to thinking about pensions is to look at the likely cash flows for current and former employees.

Here’s my scenario: a municipality decides to terminate its overly generous defined benefit [DB] plan, and though it is 30% underfunded, they agree to not let underfunding get greater than 30%. Sadly, the discount rate on the pension cash flows is 8%/yr, but the likely investment earnings rate is 6%/year.

Here’s the graph of pension payments to beneficiaries, and contributions to the plan:

At the beginning of this scenario, pension payments were 10% of the municipality’s budget. Assuming taxes only grow at the rate of 2%/year, contributions to pensions are not less than 10% of the municipality’s budget until 2049. As a share of the budget, it peaks out at 32% from 2032 to 2035. It’s over 20% from 2022 to 2043.

30% underfunding isn’t that uncommon, and discount rate assumptions of 8% aren’t that uncommon either. Would that all municipalities were at discount rates of 6%, or at my more likely view, 4%.

But it doesn’t matter. We can argue over assumptions. The cash flows actually paid to beneficiaries do not rely on assumptions. The assumptions exist to try to allow pre-funding, so that municipalities fund their plans to the same degree that benefits are accrued. Some municipalities have done that with pensions, almost none have done it with retiree healthcare, but the retiree healthcare promise is much weaker one. You can turn it from a Cadillac plan to hospice care, in many cases. In this case the state constitution matters a great deal, so do your own homework here.

Part of my advice to you is to watch weaker states and municipalities, like Puerto Rico, Illinois, Chicago, Pittsburgh, and many others. I don’t have all of the data in front of me. This is one of those cases where relative standing is important. People will migrate out of areas with low funding, and high expected payments, and into municipalities with higher funding, and lower expected payments in relative terms.

You will see municipalities depopulate, because the taxes are disproportionate to the increasingly slim services rendered, because much of the revenue pays for the overly generous past promises to retirees. As a result, you will see more municipal bankruptcies. I would expect that you would see most of the bankruptcies in the 2020s.

I know that’s vague, but I think it is more defensible than Meredith Whitney’s notable statement a few years ago. The pension cost curve is inexorable, and I suspect most municipalities can bear it for the next six years, but will have a hard time with it as the tail end of the Baby Boomers retires in the 2020s.

Advice

1) If you are in an area under pension stress, if you at all can, not harming your existing earnings, move to an area not under that stress. Remember, as other people move, it will become increasingly difficult to maintain existing services. Think of the slow police response times in Detroit, and packs of stray dogs that roam the city.

2) If you work for a municipality, consult your state constitution to see what you are guaranteed. In many cases, healthcare will not be covered. Even existing pension benefits in payment now may be under threat in a default. Be aware.

This is one of those cases where the rich will get richer, and the poor will get poorer — better to be on the rich side of the line, and sooner.

Final Note

All that said, we face the same issues with Social Security and Medicare, though both are unfunded. At present, Social Security’s payments will be cut by 25% or so in 2026, unless some adjustment is made to the system. Medicare is another issue, and the question is what will it cover. It could be stripped back a great deal when the US realizes it can’t fund a generous system that extends life a few years at high cost.

My main point to all of my readers is to be aware of the imbalances in the existing systems, and be ready for the coming adjustments, because the US economy will not be willing to make all of the payments that have been promised to oldsters who have served the public.

No Comments "

October 3rd, 2013

By David Merkel.

I’ve received two notes recently on Closed-end Leveraged Muni BondFunds. Here’s one:

David,

I have been asked several times about the Blackrock Target Term Municipal Bond Trust (“BTT”). The appeal is obvious: at $17, it offers a 7% tax free yield. A theoretical $25 redemption price in about 15 years adds roughly 2.5% per year to the total return (not tax free, but at least tax deferred).

All wonderful stuff. What I do not understand is the leverage via Tender Option Bonds. I realize TOB’s equate to borrow short/lend long, which has obvious risks, but the range of outcomes and probabilities is beyond me.

Can you shed some light on this?

And here is the other:

What about the closed end funds of Eaton Vance that are trading at a discount to their nav? I’m thinking specifically of the muni one EIV?

Also do you know the statistics of how many munis go to maturity vs getting called in 10 years?

Thank you for all you do to educate your reader!

I responded to the latter:

http://funds.eatonvance.com/Municipal-Bond-Fund-II-EIV.php

With CEFs, I look at the fund’s website, which I note above. This funds has a lot interest rate sensitivity, and a lot of oddball credits, many of which are insured to AA. Remember that many guarantors failed in the last crisis. The question iseconomic necessity of existence for each creditor, which would take a lot more work to determine.

I don’t have any data on calls, but given the falling rate environment, most healthy credits that could call, did call. It would be stupid not to call.

But with respect to the former:

You can get the basic data on BTT here:

https://www2.blackrock.com/webcore/litService/search/getDocument.seam?contentId=1111182509&Venue=PUB_IND&Source=WSOD

The levered fund duration is astounding at 17.5 years. A 30-year Treasury does not have that level of interest rate sensitivity. The question to you is what is your time horizon? Can you buy and hold, and if you do, will inflation and defaults eat you up?

I am not inclined to buy either EIV or BTT. Municipal finance is not what it used to be, and players should recognize the weakened position of municipal borrowers. The rating agencies are looking through the rear-view mirror to rate munis.

No, things are not as bad as Meredith Whitney posited, but they are bad, and the understatement of employee benefit liabilities are significant.

On tender option bonds, you have it basically right, and there is not much more to it than what you said, but here is the full treatment from Nuveen.

Here’s the trouble with muni bond portfolios: to get a great yield you have to take a lot of the following risks:

- Liquidity

- Credit

- Guarantor

- Leverage

- Duration

These are not trivial risks, and so I am unlikely to invest in high yielding municipal bond Closed End Funds.

http://alephblog.com/2013/09/26/on-leveraged-municipal-bond-closed-end-funds/

No Comments "

June 8th, 2013

By David J. Merkel.

What does it take to create a global or national financial crisis? Not just a few defaults here and there, but a real crisis, where you wonder whether the system is going to hold together or not.

I will tell you what it takes. It takes a significant minority of financial players that have financed long-dated risky assets (which are typically illiquid), with short-dated financing.

The short-dated financing needs to be rolled over frequently, and during a time of financial stress, that financing disappears, particularly when creditors distrust the value of the assets. It typically happens to all of the firms with weak liability structures at the same time.

During good times financing short is cheap. Locking in long funding is costly, but safe. That is why many financial firms accept the asset-liability mismatch — they want to make more money in the short-run in the bull phase of the market. But when many parties have financed long risky assets with loans that need to be renewed in the short-term, the effect on the markets is multiplied. The value of the risky assets falls more because many of the holders have a weak ability to hold the assets. Where will the new buyers with sound finances come from?

Areas of Short-dated Financing

Short-dated financing is epitomized by bank deposits prior to the Great Depression. If doubt grew about the ability of a bank to pay off its depositors, depositors would run to get their cash out of the bank. Deposits are supposed to be available with little delay. After creation of the FDIC, deposits under the insurance limit are sticky, because people believe the government stands behind them.

But there are other areas where short-dated financing plays a significant role:

- Margin accounts, whether for derivatives, securities, securities lending, etc. If a financial company is required to put up more capital during a time of financial stress, they may find that they can’t do it, and declare bankruptcy. This can also apply to some securities lending agreements if unusual collateral is used, as happened to AIG’s domestic life subsidiaries.

- Putable financing, particularly that which is putable on credit downgrade. This has happened in the last 25 years with life insurers [GICs used for money market funds], P&C reinsurers, and utilities. Now this is similar to margin agreements on credit downgrades because more capital must be posted. Anytime a credit rating affects cash flows, it is a dangerous thing. The downgrade exacerbates the credit stress. Then again, why were you dancing near the cliff that you created?

- Repo financing was a large part of the crisis. The weakest large investment banks relied on short-term finance for their assets in inventory. So did many mortgage REITs. As repo haircuts rose, undercapitalized players had to sell, lowering asset prices, leading to a new round of selling, and higher repo haircuts. It was the equivalent of a bank run and only the strongest survived.

- Auction-rate preferreds — a stable business for so long, but when creditworthiness became a question, the whole thing fell apart.

- Finance companies — GE Finance and other finance companies rely on a certain amount of short-term finance via commercial paper. It is difficult to be significantly profitable without that.

- All other short-term interbank lending.

Crises happen when there is a call for cash, and it cannot be paid because there are not enough liquid assets to make payment, and illiquid assets are under stress, such that one would not want to sell them. This has to happen to a lot of companies at the same time, such that the creditworthiness of some moderately-well capitalized institutions, that were thought to have adequate liquidity are called into question.

The Value of a Long Liability Structure

Let me give a counterexample to show what would be a hard sort of company to kill. In the mid-1980s, a number of long-tailed P&C reinsurers found their claims experience in a number of their lines to be ticking up dramatically. But the claims take a long time to settle, so there was no immediate call for cash. Later analysis showed that for many of the companies, if the full value of the claims that eventually developed were charged in the year the business was written, many of them would have had negative net worth. As it was, most of them suffered sub-par profitability, losing money on the insurance, and making a little more than that on their investments.

But they survived. Other insurers cut some corners in the ’90s & ’00s and wrote policies that were putable if their credit was downgraded. This would supposedly give more protection to those buying insurance or GICs [Guaranteed Investment Contracts] from them. Instead, the reverse would happen when the downgrade came — there would be an immediate call on cash that could not be met, and the company would be insolvent. Even if the majority of the liability structure is long, if a significant part of it was short, or could move from long to short, that’s enough to set the company up for a liquidity crisis of its own design.

Credit cycles come and go. The financial companies in the greatest danger are the ones that have to renew a significant amount of their financing during a crisis. It’s not as if firms with long liabilities don’t face credit risk; they face credit risk, and sometimes they go insolvent. But they have the virtue of time, which can heal many wounds, even financial wounds. If they die, it will be long and drawn out, and they will hold options to influence the reorganization of the firm. Creditors may be willing to cut a deal if it would accelerate the workout, or, they might be willing to extend the liability further, in exchange for another concession.

In any case, not having to refinance in a crisis makes a financial company immune from the crisis, leaving aside the regulators who may decide the regulated subsidiaries are insolvent. But, the regulators may decide they have more pressing issues in a crisis from firms that can’t pay all their bills now.

AIG, Prudential & GE Capital

So the Financial Stability Oversight Council [FSOC] has designated AIG, Prudential & GE Capital as systemically important. They are certainly big companies in their industries, but are they 1) likely to be insolvent during a credit crisis, and 2) does the failure of any one of them affect the solvency of other financial firms?

That might be true for GE Capital. They certainly still borrow enough enough in the commercial paper market, though not as much as they used to. If GE Capital failed, a lot of money market funds would break the buck.

AIG? The current CEO says he doesn’t mind being being systemically important. Still, Financial Products is considerably smaller than it was before the crisis, they aren’t doing the same foolish things in securities lending that they were prior to the crisis, and they don’t have much short-term debt at all. The liabilities of AIG as a whole are relatively long. And even if AIG were to go down, we shouldn’t care that much, because the regulated subsidiaries would still be solvent. Financial holding companies are by their nature risky, and regulators should not care if they go bust.

But Prudential? There’s little short term debt, and future maturities are piddling on long term debt. If the holding company failed, I can’t imagine that the creditors would lose much on the $27B of debt, nor would it cause a chain reaction among other financial companies.

I feel the same way about Metlife; both companies have long liabilities, and would have little difficulty with financing their way through a crisis. Just slow down business, and free cash appears in the subsidiaries.

I can make a case that of these four, only GE Capital poses any systemic risk, though I would have to do more work on AIG Financial Products to be sure. But what the selection of companies says to me was it was mostly a function of size, and maybe complexity. Crises occur because a large number of financial companies finance long-dated assets with short-dated borrowings. I think the FSOC would have done better to look at all of the ways short-term finance makes its way into financial companies, and then stress test the ability to withstand a liquidity shock.

My belief is that if you did that, almost no insurers would be on such a list; the levels of stress testing already required by the states exceed what FSOC is doing.

http://alephblog.com/2013/06/05/on-the-designation-of-systemically-important-financial-institutions/

No Comments "

May 29th, 2013

By David Merkel.

Mark Hulbert had a recent piece in the Wall Street Journal called How to Use Stock Splits to Build a Winning Portfolio. I find it curious, because 31 years ago I wrote my Master’s Thesis called, “Predicting Stock Splits: An Exercise in Market Efficiency.” As far as I know, aside from the unbound copy sitting next to me, the only other copy is in some obscure part of the Johns Hopkins Library System. If a number of people are really curious about this, I could try OCR and see if that would adequately read the typewritten text.

But anyway, I find it amusing that some are still trying to use stock splits to try to make money. Quoting from Hulbert’s piece:

But try telling that to Neil Macneale, editor of an investment-advisory service called “2 for 1,” whose model portfolio contains only those stocks that have recently split their shares, holding them for 30 months. Over the past decade, according to the Hulbert Financial Digest, that portfolio has produced a 14% annualized return, far outpacing the 8% gain of the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index, including dividends.

Mr. Macneale’s track record isn’t a fluke. Several studies have found that the average stock undergoing a split outperforms the overall market by a significant margin over the three years following the company’s announcement of that split. Indeed, Mr. Macneale said in an interview, he got the idea for his advisory service in the 1990s from one of the first such studies, conducted by David Ikenberry, now dean of the Leeds School of Business at the University of Colorado, Boulder.

Research on stock splits goes back to the ’30s. In the ’50s & ’60s before MPT got into full swing, a few researchers began trying analyze why there were abnormal rises in stock prices two months before a stock split. Could it be that other factors affecting future value were somehow associated with stock splits? Many factors pointed toward that, notably prior price increases, prior earnings increases, and increases in the dividend associated with the stock split. Little did they know that they were anticipating momentum investing.

The consensus by the end of the ’70s was that there was no excess return after the stock split announcement, and few ways if any to capture the pre-announcement excess returns. If in the present stock splits are providing excess returns for 2.5 years afterward, well, this is something new.

One of the leading stock-split theories—supported by the work of professors Alon Kalay of Columbia University and Mathias Kronlund of the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign—is that companies implicitly have a target range for where they would like their shares to trade.

If a firm’s shares are trading well above that range, and management believes that this high price is more than temporary, it is likely to initiate a split in order to bring its share price back to within that range.

This isn’t a new theory — it goes back to the ’50s, if not earlier. One of the oldest theories was that it improved liquidity, but back in a time of fixed tick sizes, where everything traded in eighths, and higher commissions, that made little sense to a number of economists. Splits made trading costs rise in aggregate for the same amount of dollar volume traded.

In the present though, there are many venues for execution of trades, commissions are much smaller, and negotiable. Perhaps today more shares at lower prices does add liquidity, and the way to test might compare the bid-ask spread and sizes pre- and post-split.

The professors late last year completed a study of all U.S. stocks that split their shares by a factor of at least 1.25-to-1 between January 1988 and December 2007. They say the evidence their study uncovered suggests that splits are an “indication of sustained strong earnings going forward.” It therefore shouldn’t be a big surprise that split stocks outperform other high-price stocks that don’t undertake a split.

What this might mean is that stocks that split are examples of price and/or earnings momentum. A management team splits the stock as a signal that corporate profit growth has been good, and will continue to be so. If not, the management team runs the risk that if the stock price falls, it looks bad to a management to have a low stock price. There are some investors who won’t buy stocks below $10, $5, etc. Why run the risk of lowering your stock price if you think the odds are decent that the price will fall from there? Low stock prices affect the confidence of many.

Investors looking to profit from the stock-split phenomenon should shun stocks that have undergone a reverse split and focus instead on those that have split their shares. You will have to invest in such stocks directly because there is no mutual fund or exchange-traded fund that bases its stock selection on stock splits.

Fortunately, constructing a portfolio of such stocks needn’t be particularly time-consuming.

For example, there is no need to guess in advance which companies are likely to split their shares—which in any case would be difficult, if not impossible, to do. There even appears to be no need to buy a company’s stock immediately after it announces a split, since research shows that it is likely to outperform the overall market for up to three years following that announcement.

Still, Mr. Macneale recommends that investors be choosy when deciding which post-split stocks to purchase. He cites several studies suggesting that the post-split stocks that perform the best tend to be those that, at the time of their splits, are trading at relatively low price/earnings or price/book ratios. Both are commonly used measures of a stock’s valuation, with lower readings indicating greater value.

I’m going to have to find the papers that say that post-split stocks outperform for the next 30 months. Doesn’t sound right — a result like that would have been found from the research pre-1980, and no one suggested that; in fact, the evidence contradicted that consistently.

Note that the investment manager in question uses cheap valuation to filter opportunities. That the stock has split usually indicates strong price momentum. Value plus momentum is usually a winner, so why should we be surprised that stock splits often do well?

But I know of three papers that focused on predicting stock splits — two in 1973, and mine in 1982. It’s not that hard. Most of it is price momentum, and with a balanced set of stocks that would and would not split, the models predict 70% of the companies that would split.

What’s better, is that the formulas to predict stock splits pick good stocks in their own right — they end up being value and momentum, and maybe a few other factors. I remember my thesis adviser being surprised at how good my models were at picking stocks.

This brings me to my conclusion: stock splits are a momentum effect, but it is larger when companies are still have a cheap valuation. Perhaps splits have no effect on stock performance — it is all momentum and valuation. To me, that is the most likely conclusion, and my thesis anticipated quantitative money management by 10+ years.

In one sense it is a pity I didn’t do anything with it, but if I hadn’t become an actuary, I would never have gained many other insights into the ways that the market works. I’m happy with the way things worked out.

No Comments "