Posts by HakimKhatib:

Could Integration Prevent Radicalization of Muslim Youth?

November 1st, 2016

By Hakim Khatib.

GERMANY/Hessen – Radicalisation is a phenomenon that has been striking not only in parts of Asia and Africa but also in the heart of Europe. While the number of Muslims in Germany is estimated by 4,7 millions (5,8%), 70% of the almost 900,000 asylum-seekers have arrived in recent years are believed to be Muslims. It is undeniable that there is discrimination in Germany, and it is equally undeniable that more on issues of integration and conflict prevention should be done. Thus, could effective integration processes prevent radicalisation of the Muslim youth in Europe? Read the rest of this entry “

Comments Off on Could Integration Prevent Radicalization of Muslim Youth?

Cultural Bridging in Amman – Grassroots Projects with Scarce Resources

March 22nd, 2016JORDAN – While political conflicts have dominated almost all discourses around the region of West Asia, narratives on the region have remained ensnared by political and religious frameworks. Thus the people in West Asia remain entrapped within politically driven explanations to answer questions about peace and conflict, Islamism, authoritarianism, security, stability etc. Unfortunately, even cultural, historical, philosophical, psychological and archaeological aspects of human civilisation in this region were to a great extent framed to serve only political explanations. This has led to minimizing the complexity of the fabric of these societies.

Defying these rigid structures of categorization, local people in Jordan with very scarce resources are attempting to create, elevate and implement innovative ideas on very local levels. The aim is to raise awareness and develop new ways of thinking that might be the path forward not only for improving the lives of the people in the region but also for enhancing the cultural dialogue between the orient and the occident. The impact of such projects might still be barely noticeable on a macro-scale; yet their impact is significant on the micro-level in the Jordanian society. Read the rest of this entry “

Comments Off on Cultural Bridging in Amman – Grassroots Projects with Scarce Resources

The Taboo of Atheism in Egypt

February 4th, 2016By Hakim Khatib

Acknowledging the rights of atheists doesn’t mean adopting their ideas. While atheists just don’t believe in one further religion in comparison to believers, everyone should be entitled to express their ideas and thoughts without intimidation. Challenging religious oppression and rusty social traditions, many Egyptians risk their lives to uphold and protect freedoms and values of tolerance.

Systematic Discrimination

Discrimination against atheists in Egypt is primarily a product of conservative social traditions and state religious establishments – Al-Azhar mosque and the Coptic Church. Laws and policies in Egypt protect religious freedom but punish those ridicule or insult heavenly religions by words or writing – i.e. insulting Budhism or Hinduism is not punishable by the Egyptian law but insulting Islam, Christianity or Judaism is. Between 2011 and 2013, “Egyptian courts convicted 27 of 42 defendants on charges of contempt for religion,” according to The Guardian.

Interestingly, an Egyptian citizen is only entitled to one of the three monotheistic religions, namely Islam, Christianity and Judaism. In other words, people are allowed to believe or disbelieve in any religion for obvious reasons, but they are not allowed to have their beliefs or disbeliefs legally recognized. Therefore, on official records, all people have to be categorized as such. Diversity in this sense is systematically blinded.

According to official statistics, religious beliefs in Egypt are as follows: 90-94% are Sunni Muslims and 6-10% are Coptic Christians. While atheism is not limited to a specific segment of the Egyptian society, credible research is still lacking on the matter. It is simply because being without religion is a taboo in Egypt.

Similar to their declared wars on terrorism, corruption and neglect, political and religious state institutions launched a new “war on atheism”.

In a 2014-report, Dar Al-Ifta Al-Misriyyah (Al-Azhar center for Islamic legal research) confirmed that the number of atheists in Egypt is no more than 866 individuals – i.e. the proportion of atheists is 0.001% of the Egyptian population. While the methods Al-Azhar “scholars” used to reach this precise figure remain unknown, discriminatory discourse against atheists is commonplace in Egypt.

This discriminatory discourse is especially accentuated by Al-Azhar mosque and the Coptic Church. Starting from 2014, both institutions have been cooperating to fight against atheism in order to “save the Egyptian society”. In the same year, the government embarked a “national campaign” to combat the spread of atheism among young people using the help of a number of psychologists, sociologists and political scientists.

Nemat Satti, chairman of the Central Administration of the parliament and civic education at the Ministry of Youth and Sports, said to Shorouk News in 2014 that the phenomenon of atheism has become as noticeable and widespread among young people as the phenomena of harassment, rape and extremism. The comparison is pretty clear.

Media Discourse Against Atheists

This discriminatory discourse against atheists can be detected in the Egyptian media as well. Egyptian media is not neutral when addressing the issue of atheists in the society. Similar to the governmental and religious campaigns, media portrays atheists as patients with mental disorder, who need treatment to get rid of the illusions they are talking about.

For instance, in 2015 in her program “the morning of the capital” on the Egyptian channel “the Capital TV” (Al-Asima), an Egyptian journalist throws out an atheist guest on air for his ideas. A wrangle broke out between the Egyptian journalist Rania Mahmoud Yaseen, the host of a debate on atheism, and her atheist guest Ahmed Al-Harqan, who spoke about “the lack of historical evidence concerning the existence of the figure of the prophet Mohammad”.

Rania Yasin interrupted Al-Harqan saying: “Come on! Leave! We don’t need Atheists or infidels. People should pay attention to the warnings against infidelity, atheism and these outrageous ideas in the society.”

Hence the guest left the debate, it remains to wonder why an Egyptian journalist hosts a debate about such a sensitive issue in Egypt, if she isn’t willing to listen to what atheists have to say.

Stories of Persecution

While the stories of persecuting atheists in Egypt are numerous, here are some cases to show how this taboo is being handled systematically. So far, there is no evidence that the change of the head of the government or the government’s political orientation correlates with the number of attacks against atheists.

In 2014, Karim Ashraf Mohamed Al-Banna, 21, was jailed for three years for “insulting Islam” by simply declaring he is an atheist on Facebook. Shockingly, his own father testified against him claiming that his son “was embracing extremist ideas against Islam”.

In 2013, Egyptian clerics such as Al-Azhar professor Mahmoud Shaaban, a member of Al-Jama’a Al-Isalmiyya Asem Abelmajed and a Salafi scholar Abu Ishaq Al-Heweny issued an Islamic ruling (fatwa) against Hamed Abdel-Samad for writing a book on Islamic fascism. Abdel-Samad was accused of being heretic and must be killed for it. Shaaban said on Al-Hafez TV that: “after he [Abdel-Samad] has been confronted with the evidence, his killing is permitted if the [Egyptian] government doesn’t do it.”

In 2012, the Egyptian blogger Alber Saber was sentenced to three years in prison for insulting Islam by posting the trailer of the YouTube video Innocence of Muslims on his Facebook page. While prosecution didn’t find the trailer on Saber’s Facebook account, they accused him of religious blasphemy after finding a short video of Saber criticizing both Islamic and Coptic religious leaders and institutions.

After detaining Saber for religious blasphemy, “police incited the prisoners against Saber, claiming that he was an atheist and insulted the prophet Mohamed,” stated the 2012 Report On Non-Religious Discrimination. Consequently, one of the prisoners injured Saber with a razor blade.

According to the same report, there were similar incidents in 2012 against individuals who allegedly insulted Islam or the prophet Mohammad such as the Christian school secretary Makram Diab, who was sentenced to six years in prison, Ayman Yusef Mansur, 24, who was sentenced to three years in prison with hard labor.

These are not the first incidents in Egypt against atheists. In 2007, the blogger Abdel Kareem Soliman was sentenced to four years in prison for insulting Islam and the president. Another blogger, Kareem Amer, was sentenced to three years in prison for “Facebook posts deemed offensive to Islam”, according to 2012 Report On Non-Religious Discrimination.

While atheism in Egypt remains a taboo, systematic discrimination against atheists remains significant. Prompted by conservative traditions and state religious and political establishments, there are restrictions that deny atheists the right to engage in a serious debate about their fundamental rights.

Comments Off on The Taboo of Atheism in Egypt

The Controversy of Blasphemy in Egypt

February 2nd, 2016By Hakim Khatib

What is that again? Blasphemy law?

An Egyptian court sentenced the Islamic scholar and theologian Islam Al-Buhairi to one year in prison for blasphemy. Al-Buhairi was accused of insulting Islam in his TV show “With Islam Al-Buhairi” on “Al-Qahira wa Al-Nas” channel. Al-Buhairi questioned the “Islamic heritage”, which angered the Al-Azhar scholarship.

Confused to say luckily or sadly, this sentence against Al-Buhairi was softened from five years to one year. Al-Buhairi’s lawyer Jamil Saad told AFP: “Islam Al-Buhairi didn’t insult religions because the pillars of Islam are the Quran, Allah and the Day of Judgment and he didn’t come close to these circles at all.”

Engaged in a demonstration of Egyptian liberal intellectuals against the conviction of Al-Buhairi, Sheikh Muhammad Abdullah Nasr said: “Blasphemy is a fascist law. It is a legacy of the Spanish inquisition courts.”

But what did Al-Buhairi really do?

Al-Buhairi’s Blasphemy

Al-Buhairi criticised several books of Islamic interpretation, which according to him include radical interpretations of the Quran and the Sunnah. Al-Buhairi argued in his program that these radical interpretations constitute the basis for extremist organizations such as the “Islamic State” and “Al-Qaeda”.

According to Al-Buhairi, the followers of the prophet Muhammad are the ones who were born or converted to Islam after the demise of the Prophet Muhammad.

“The followers [of the prophet] have no sanctity. They were men and we are men,” said Al-Buhairi referring to the need of scrutinizing the Hadith collections of Mohammad Al-Bukhari and Muslim Al-Hajjaj, Persian Islamic scholars lived in the ninth century.

The Former authored the hadith collection Sahih Al-Bukhari including 7257 sayings and acts of the prophet Muhammad, whereas the latter authored the hadith collection Sahih Muslim including 9200 acts and sayings of the prophet Muhammad.

Al-Buhairi called for examining the interpretations of other ‘men’. He also demanded from Islamic scholars to stop taking Islamic sources for granted because they sometimes contain discriminatory, violence-inciting and illogical arguments

“They had opinions which we would never be able to imagine. This is what we inherited.

“All the bloodiness, killing, sectarianism, backwardness and extremism we are living have jurisprudential basis and not related to the manuscript,” Al-Buhairi explained.

Furthermore, Al-Buhairi accused the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar Sheikh Ahmed Al-Tayeb of doing nothing to reform traditional curriculum of Al-Azhar and to limit the Muslim Brotherhood’s influence in Al-Azhar.

Fatwas (Islamic rulings) of Al-Azhar, Al-Buhairi claims, don’t cope with contemporary developments and ways of life followed by the Egyptian citizens.

Al-Azhar’s Debate With Al-Buhairi

While Al-Azhar refused to call ISIS militants infidels (Kafer) claiming not to have the right to call Muslims infidels no matter what their sins were, Al-Azhar initiated court proceedings against Al-Buhairi. Cosequently, Al-Azhar committee, on behalf of Ahmed Al-Tayeb, filed a case against Al-Buhari in April 2015 for “calling the precepts of religion in question and inciting a communal strife among Muslims.”

Media Centre of Al-Azhar told Egypt Independent in 2015 that Al-Azhar’s position rejects Al-Buhairi’s views describing him as abnormal and deliberately undermining the imams and scholars of Islam. Al-Buhairi, according to Al-Azhar scholarship, is ignorant or unaware of the great Islamic heritage, which has enriched the Islamic library and even the world.

The Egyptian hard-line Salafist Abu Ishaq Al-Huwaini described Al-Buhairi last year as an ignorant, who thinks “Christians are not infidels”. The Salafi Muhammad Hassan said: “Throughout history, those who fought against Allah and his messenger have never succeeded.”

It is noteworthy that after hundreds of years as an independent institution, Al-Azhar was nationalized in 1961 by former President Jamal Abdel Nasser. Since that time, Al-Azhar has become inseparable from the government. It has become the official institution to oversee cultural and educational materials related to the Islamic faith.

Al-Sisi’s Islamic Revolution

In a speech to Al-Azhar scholars on 01 January 2015, Abdulfattah Al-Sisi said: “we are in need of a religious revolution […] That thinking—I am not saying “religion” but “thinking”—that corpus of texts and ideas that we have sacralised over the years, to the point that departing from them has become almost impossible, is antagonizing the entire world.”

Al-Buhairi’s statements can be seen as a part of a campaign to renew the Islamic discourse initiated by Al-Sisi upon his presidential win in 2014. Controversially, Al-Sisi needs Al-Azhar, which is responsible for the content of sermons in more than 140,000 mosques across Egypt. Thus Al-Sisi pointed out clearly that all changes in religious discourse should be within the framework of the state apparatus and headed by Al-Azhar institution.

In response to Al-Buhairi’s thoughts, Al-Sisi said in April 2015 that: “When I spoke about religious discourse, I just posed a title and did not go into detail,” claiming that he doesn’t agree with Al-Buhairi’s statements.

Blasphemous Critical Thinking

While a spirit of critical thinking can be detected in the writings of many Egyptian intellectuals about sensitive religion-related topics, these intellectuals have been systematically subjected to hate campaigns and crimes according to the Human Rights Watch. Here are two examples:

The story of professor Farag Foda in the beginning of 1990s, an activist in the field of human rights, is a case in point. He was assassinated by Al-Jama’a Al-Islamiyya in 1992 not because of his atheism and infidelity but because of his harsh criticism of the violence of the armed Islamic groups. While Foda was a critic of religious intolerance, his murderers, religious zealots, proved him right. Because the killers didn’t like Foda’s writings, they simply killed him.

The Egyptian liberal theologian and university professor Nasr Hamid Abu Zayd also suffered a major religious persecution in the 1990s and had to flee to the Netherlands to be safe. The crime of Abu Zayd was his academic work. When certain individuals refused to accept his academic research, they took it to the Egyptian court instead of the Egyptian debate. The court declared him an apostate and based on this sentence, he was not to remain married to his wife Ibtihal Younis, a French Literature professor. The logic behind the forced divorce is that Muslim women are not permissible to marry non-Muslims.

Constitutionally, Blasphemy (contempt of monotheistic religions) is based on the article 98 of the Egyptian Penal Code, which was added 1982 and then amended in 2006. According to this law, citizens who insult or ridicule heavenly religions, propagate extreme ideas for the purpose of inciting strife or contribute to damaging national unity can be confined for a period of no less than six months and no more than five years. This is, in other words, a legal licence for the Egyptian state and its religious institution to persecute its own intellectuals.

This article was also featured on MPC Journal.

Comments Off on The Controversy of Blasphemy in Egypt

Rivalry Between Saudi Arabia and Iran Not About the Victim but the Aggressor

January 30th, 2016By Hakim Khatib

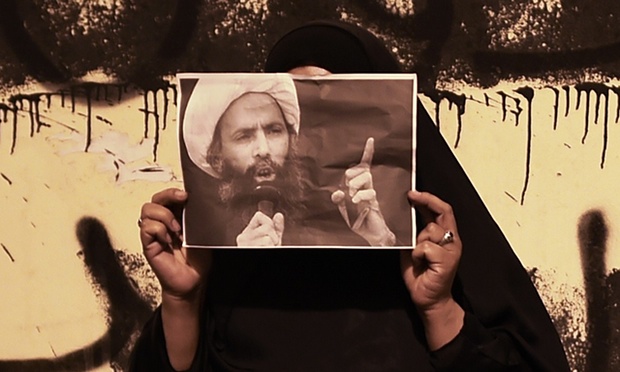

Tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran have been increasing recently. Although the narrative developed to describe the execution of a Saudi Shiite cleric, Nimr Al-Nimr, as a sectarian dimension of the Kingdom’s policies towards Iran, Saudi Arabia’s goals are not principally fuelling the Shiite-Sunni divide. The Saudi executions were partially an attempt by Saudi Arabia to severe ties with Iran and push the tensions forward. Lifting sanctions against Iran, coupled with oil prices plummeting to around $32 per barrel remains a frightening nightmare for the Saudis.

Following the execution of Al-Nimr, diplomatic relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran trembled and could affect Saudi Legalisation. Iran promised Saudi Arabia that it would pay a high price over the execution of Al-Nimr, whereas the latter described the Iranian criticism of its judicial system as “blatant interference” in its internal affairs.

Escalating very quickly, Iranian demonstrators broke into the Saudi embassy in Tehran and started fires, souring the already troubled relations between the two regional rivals. Crossing the line, Iran compared Saudi Arabia to ISIS following the executions. A website associated with Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, published a picture of a Saudi executioner (dressed in white) next to an Islamic State executioner (dressed in black) with the caption “Any differences?”, drawing attention to the fact both carry out beheadings.

War of Words

Slamming the Saudi monarchy, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif said in an op-ed in The New York Times on 10 January that “Today, some in Riyadh not only continue to impede normalization but are determined to drag the entire region into confrontation.” Zarif accused Saudi Arabia of “active sponsorship of violent extremism” and “barbarism”, referring to the recent executions.

The Saudi Foreign Minister Adel Bin Ahmed Al-Jubeir responded with an op-ed in the New York Timeson 19 January accusing Iran of supporting terrorism in the region and in the world. Al-Jubeir said that Iran “opts to obscure its dangerous sectarian and expansionist policies, as well as its support for terrorism, by leveling unsubstantiated charges against the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.” Al-Jubeir continued to list the atrocities attributed to Iran since the Islamic revolution in 1979, charging Iran of being “the single-most-belligerent-actor in the region”. Jubeir’s comments appeared after Saudi Arabia’s Foreign Ministry had published a “sheet of facts” listing all the nefarious practices of the Islamic Republic.

Khalid al-Dakhil, a Saudi political commentator based in Riyadh told Al Jazeera that: “Iran executes far more people a year than Saudi Arabia, but it does not get the negative publicity Saudi Arabia has. This is something that must be addressed.”

Sectarian Divide?

When considering sectarianism in Islam, we should emphasize that most Muslims are not from Saudi Arabia or from Iran. Indeed most Muslims in the world don’t live in the Middle East. According to 2015 Intercensal Population Survey, the population of Indonesia is around 250 million, which is more than the population of all Middle Eastern countries (around 200 million) combined. If we are to believe that the number of Muslims in the world is around 1.5 billion, this leaves the land of the two holy mosques – Saudi Arabia – and the Islamic Republic of Iran significantly outnumbered. According to the Central Department of Statistics and Information in Saudi Arabia, the annual number of pilgrims (those who take on a journey to the sacred places of Mecca and Medina) over the past ten years was between 1.5 and three million. On average, the number of pilgrims to Mecca over the past ten years is around 24 million, which is insignificant compared to the number of Muslims worldwide. The number of visitor for religious purposes is even less than the population of Yemen.

At a first glance, the tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia can be marked as sectarian but looking more profoundly, it becomes clear that it is a power struggle.

The prominence of religious norms in political contexts between Saudi Arabia and Iran doesn’t owe to a sectarian divide per se, but rather to the usefulness of religion in persuasion, legitimization, mobilisation, elimination, contestation, pacification and justification In other words, it is a struggle for regional dominance. According to Language Fractionalization Index, Iran, UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon are the most linguistically fractionalised countries in the region, whereas Lebanon, Kuwait, Bahrain, Iraq, and Syria are the most religiously fractionalised. Religious divisions contribute to creating political and social structures that enforce the status quo in the Middle East. In other words, fractionalisation guarantees the ruling elites to remain exactly where they are – in power.

In addition to the sectarian dimensions mentioned above, a pattern of alliance in the Middle East, in which states, monarchies and forces define their allies and enemies based on sectarian dimensions, can be traced. On one hand, such a pattern results in minorities oppressing majorities such as in Syria, Iraq, Bahrain and Yemen. On the other hand, it results in majorities oppressing minorities such as in Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Such a pattern of alliance is also exacerbated by the two regional rivals backing opposing sides in civil wars in Syria and in Yemen. In Syria, Saudi Arabia supports Sunni but hard-line elements in Syria, while Qatar and Turkey support Sunni elements allied with the Muslim Brotherhood, whereas Iran backs the Syrian regime and Hezbollah.

In Yemen, a coalition includes Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, Jordan, Morocco, Egypt, Jordan, Sudan and “Pakistan” has been launching airstrikes, called “The Storm of Resolve”, against Houthi rebels claiming to defend the “legitimate Yemeni government” of Abdrabbu Mansour Hadi. Houthi rebels are a Yemeni Shiite minority in northern Yemen accused of being backed by Iran. Many Yemeni civilians including children were killed by the airstrikes similar to what we see in Syria.

Religion remains an identifying factor (not identity). A Shiite person is more likely to support Houthi rebels in Yemen, for instance, while a Sunni is more likely to support Syrian rebels.

Noam Chomsky described the latest airstrikes against Yemen as an “extreme form of terrorism”. “Yemen has been the main target of the global assassination campaign–the most extraordinary global terrorism campaign in history – it is officially aimed at, as in this last strike, people who are suspected of potentially being a danger to the United States,” Said Chomsky on Russia Today commenting on Saudi Arabia’s involvement in Yemen.

Majority-Minority Binary

Discrimination is commonplace in the Middle East. In both, Iran and Saudi Arabia, political activists are not only taken to prison for criticizing repression, but also tortured or flogged. In case of changing power structures in Saudi Arabia or Iran, in which minorities rule the majority, there is little or no evidence that the majority will enjoy the same rights and security as the victorious minorities.

In Saudi Arabia, the majority Sunni population oppresses Shiite minority rhetorically and constitutionally, while the Sunni royal family in Bahrain, backed by their Gulf allies, oppresses the Shiite majority. On the one hand, Shiites, who explicitly or implicitly show their faith, might face imprisonment in Saudi Arabia, according to Human Rights Watch (HRW). “Official discrimination against Shia encompasses religious practices, education, and the justice system. Government officials exclude Shia from certain public jobs and policy questions and publicly disparage their faith,” according to 2011 Report on Saudi Arabia. The oppression against Sunnis minority in Iran is even more staggering. Further examples can be found in Syria, in which a minority is oppressing the majority.

Saudi Arabia and Iran share, among others, two common factors: Authoritarian form of governance and concentration of power in the hands of few individuals in each country. Therefore, in an ethno-linguistically and religiously fractionalised region such as the Middle East, religion is an effective means to mobilise the masses, preserve power for the ruling elites, keep the public in check etc.

Waging wars of words, invoking sectarianism and oppressing those who don’t share political power are never about helping the victim in the Middle East, but rather about who is the aggressor.

Comments Off on Rivalry Between Saudi Arabia and Iran Not About the Victim but the Aggressor

Saudi Political Intolerance

January 30th, 2016By Hakim Khatib

Beheadings in public, including a prominent Saudi Shiite cleric, prompted reactions not only inside Saudi Arabia but also in Iran, Iraq and most recently in Bahrain.

Saudi Arabia’s death wedding in January 2016 signals the Kingdom’s intolerance towards any dissent against the royal family. The Saudi law of January 2014 doesn’t “merely criminalise dissent”, but defines it as “terrorism”, according to The Independent.

While claiming to fight against terrorism, Saudi Arabia is looking forward to settle political scores inside and outside its borders. The executions are not a precedent for Saudi Arabia. Only in 2015, the average of executions reached 12 persons every month. Western Allies, Saudi Arabia and other Gulf States know that no consequences to account for. Historically, western powers have nearly always turned a blind eye to atrocities attributed to their Gulf allies because of economic calculations such as import of oil and export of arms. Thus, historical allies are unwilling or unable to make a real change.

Recent Escalations

Expanding across the region, violent clashes broke out between police forces and demonstrators on 23 January in the Bahraini Island Sitra, close to the capital Manama. These clashes came in the context of the on going three-week-protests to condemn Saudi Arabia’s execution of Nimr Al-Nimr.

Saudi Arabia’s ambassador in Iraq Thamer Al-Sabhan said to Al-Sumaria TV that: “Iraqi reactions to the execution of Al-Nimr has raised eyebrows in the Kingdom, especially that they did not condemn the attack on our embassy in Iran.” Al-Sabhan revealed that the Saudi embassy in Baghdad had “received serious threats” following the executions.

Hundreds of Al-Nimr supporters marched in Al-Qatif in Saudi Arabia’s eastern province in protest at the execution. The protestors were chanting: “Down with the Al-Saud!”, the name of the Saudi royal family.

Contrary to Saudi Arabia, Iran considers Al-Nimr as “the champion of a marginalised Shiite minority” in the Arabian Peninsula. Al-Nimr was jailed and then sentenced to death because of his political role during the times of the Arab uprising between 2011 and 2013, when he campaigned against oppression and also in support of Bahraini people. Opposition is simply abhorred in Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Style of Execution

While the world was preparing to start the New Year, Saudi Arabia was preparing for a mass execution of dozens of people on a single day. On 02 January 2016, Saudi Arabia’s Interior Ministry announced to have executed 47 prisoners on terrorism charges, including the Saudi Shiite cleric Nimr Al-Nimr. According to Reuters, beside Al-Nimr, other three of those executed were Shiite.

Saudi Ministry of Justice spokesman Mansour Al-Qufari said: “Four of the executions were implemented by firing squad, while the rest were beheaded by a sword.” Al-Qufari stressed: “Security forces will not hesitate at all to punish terrorists and instigators”.

The 47 Saudis were accused of sedition, disobedience and embracing extremist (takfiri) approach, which contains doctrines of those who went out of the main stream of Islam (Khawarej or rebels). They were accused of violating the holy book, the sanctity of Sunni consensus of the nation’s predecessors (Salaf) and participating and perpetrating murderous and terrorist acts against Saudi military and security forces.

Saudi Arabia’s Grand Mufti Sheikh Abdulaziz Al-Sheikh defended the executions as in line with Islamic Sharia and described them as “just and merciful to the prisoners.”

James Lynch, Deputy Director of the Middle East and North Africa Program at Amnesty International said that Saudi Arabia’s executions in 2015 “coupled with the secretive and arbitrary nature of court decisions and executions in the kingdom, leave us no option but to take these latest warning signs very seriously.

“Among those who are at imminent risk of execution are these six Shi’a Muslim activists who were clearly convicted in unfair trials. It is clear that the Saudi Arabian authorities are using the guise of counter-terrorism to settle political scores,” Lynch added.

Long History of Execution

Saudi Arabia enjoys a long history of executing people. According to International Amnesty report 2014/15, “authorities in Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) were unrelenting in their efforts to stifle dissent and stamp out any sign of opposition to those holding power, confident that their main allies among the western democracies were unlikely to demur.”

Over the past years, Saudi authorities made an “extensive use of the death penalty” to execute dozens by public beheading. At least 151 people were put to death in 2015, the highest recorded figure since 1995. This is an average of 12 persons every month.

Historical Allies

While some voices were shy, others were explicit in condemning the Saudi executions. Indeed, the western response to Saudi Arabia’s public beheadings is delicate in comparison with that to ISIS’s public beheadings.

UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon was dismayed by Saudi Arabia’s actions, whereas the US Secretary of State, John Kerry, said executing Al-Nimr risks “exacerbating sectarian tensions” between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

Germany’s Foreign Ministry described death penalty as an inhumane punishment. “The cleric’s execution strengthens our existing concerns about the growing tensions and the deepening rifts in the region,” Germany responded.

The Saudis and so do western allies know that the brutality of the executions is going to be forgiven similar to the Bahraini scenario during the times of the Arab uprisings. Backed by other Gulf States, Bahrain brutally cracked down protests by using live ammunition in Shiite-majority villages. At that time, shy western reactions condemning violence marked the nature of alliance between the West and the Gulf States. Joe Stork, the deputy Middle East director at Human Rights Watch described the crackdown as follows: “Bahrain has brutally punished those protesting peacefully for greater freedom and accountability while the US and other allies looked the other way.”

In the light of international indifference, there is little hope that Saudi Arabia will tolerate concerned voices, be it political, religious or social.

This article was also featured on MPC Journal.

Comments Off on Saudi Political Intolerance

What is the Syrian War about?

October 29th, 2015By Hakim Khatib

After five years of the Syrian war, we can recognize “four” conflicting parties on the ground – Assad, ISIS, rebel groups and the Kurds. Each one of these conflicting parties has regional and international backers, who ironically do not agree with each other about whom they are fighting for or against. The Syrian regime is backed by Iran, Russia, Hezbollah and Iraqi militias. ISIS is backed by the flood of global Jihadists from all over the world. Rebel groups are backed by Gulf States, Turkey, Jordan and the US. The Kurds are supported by the US. While in the media, we always say “the Syrian conflict, crisis or war”, I wonder what makes this war that much Syrian. It is rather a war on the land of Syria, in which more than 50% of Syria’s population have been displaced, over 220 thousand have been killed, and many more have been injured or imprisoned. According to Amnesty international, more than 12.8 million Syrian people are in “urgent need of humanitarian assistance”. In addition to this humanitarian catastrophe, most of the Syrian land and infrastructure have been destroyed. So what is that Syrian about the Syrian “war”?

In March 2011, when people engaged in peaceful protests against the regime, security forces and lawless secret police (Shabbiha) confronted them with brutality and killed hundreds of civilians in the first few weeks to ignite a beginning of an increasingly bloody death toll. The drivers for protests were neither ideological nor religious, but rather common people stood for their rights because they have suffered from political oppression, social injustice, economic hardship, human rights violations, unemployment, poverty, corruption etc.

While intelligence apparatus and Shabbiha, police and the army have become notoriously involved in the crackdown of peaceful demonstrations, a series of defections in the army, police, intelligence and security forces followed to form the so-called Free Syrian Army (FSA) to confront the regime’s brutality. The Free Syrian Army began to take all those who were willing to fight against regime forces under their command. At this moment, the uprising in Syria has turned into a civil war.

Prompted by ideological mobilization in 2012, Jihadists and extremists from around the world started travelling to Syria to join the rebels. Assad encouraged this activity by releasing Jihadists from jail to vilify rebel groups, especially after the regime had lost control of the northern borders. In the same year in January, Al-Qaeda formed a branch in Syria called Al-Nusra Front to fight against the regime. Around that time, Kurdish groups took up arms to defect from Assad’s rule in a search for autonomy. This year marked the beginning of the proxy war in Syria.

Iran, Assad’s strongest ally, intervened to help Assad. By the end of 2012, Iran has been sending daily cargo flights with hundreds of officers on the ground. Iran has also provided a significant logistic, technical, financial and military support to Assad. It is estimated that by December 2013, Iran has had approximately 10,000 operatives in Syria including thousands of Iranian paramilitary Basij fighters, Arabic speaking Shiite volunteers and Iraqi Shiite combatants. In mid 2012, Lebanese Hezbollah, the Iranian frontline against Israel, has joined the combat against the rebels in Syria. Hezbollah took an active role in battlefields such as in Al-Qusair battle (19 May 2013—05 July 2013) between the rebels, mainly the FSA and Al-Nusra on one hand, and Hezbollah and the regime’s troops on the other.

In return, Gulf States, namely Saudi Arabia and Qatar were sending money and weapons to rebel groups, mainly through Turkey and Jordan. Saudi Arabia supports Salafist and ultra conservative insurgent groups such as “The Army of Islam” (Jaish Al-Islam or JAI) under the command of the Salafist Zahran Aloush. Unlike Saudi Arabia, Qatar has exerted enormous efforts to support the Muslim Brotherhood and more radical rebel groups with Al-Qaeda ties in Syria. In order to counterbalance the Saudi influence in Syria, Qatar along with Turkey backed up the ultra conservative Ahrar Al-Sham (10,000—12,000 fighters), which is part of the Syrian Islamic Front (30,000 fighters) under the command of Hassan Aboud. However, Gulf States saw eye-to-eye concerning the crisis of Syrian refugees. According to Amnesty International, Gulf States offered ZERO resettlement places to Syrian refugees. However, this division between Sunni-majority powers supporting opposition on one hand and Shiite powers supporting Assad regime on the other has marked the sectarian dimension of the conflict.

Allegedly horrified by Assad atrocities against his own people in 2013, the US authorized the CIA to train and equip Syrian rebels to fight against Assad. The US has become actively participating in the war on the ground. Controversially, while the US was urging Gulf States to stop supporting extremists in Syria, Saudi Arabia bought more than $90 billion worth of arms from the United States between 2010-2015, according to the latest figures provided by the Congressional Research Service. In the same year, Assad used chemical weapons against civilians in rebel-held areas. The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons reported to the UN that “chlorine has been used repeatedly and systematically as a weapon” in Syria. In September 2013, Obama remarked: “Men, women, children lying in rows, killed by poison gas… It is in the national security interests of the United States to respond to the Assad regime’s use of chemical weapons through a targeted military strike.”

A response to the Assad regime’s use of chemical weapons went void when Russia, Assad’s long-standing ally, proposed that Assad surrenders the control over chemical weapons to the international community to be eventually dismantled. This has marked the depth of the power dispute between Russia backing Assad and the US against him.

In February 2014, ISIS, previously based only in Iraq, has taken control over areas in Iraq and Syria attracting foreign fighters from all over the world and ironically becoming Al-Qaeda’s enemy. Indeed, ISIS doesn’t fight Assad, but the Kurds in the north and other rebel groups. By 2014, foreign Jihadists were estimated to be between 10,000 and 12,000, with more than 3,000 coming from western countries. Consequently, accompanied with constant calls of, mainly non-Syrian, Sunni clergymen for “material and moral” support to the Syrian rebels, thousands of foreign fighters flood into Syria for Jihad every year.

In September 2014, a few months after the formation of ISIS, a coalition under the leadership of the US launched airstrikes against ISIS on the Syrian land. Again, CIA came into play when then sponsored training Syrian fighters, who only fight against ISIS on the ground. While the US and other western countries made it very clear that they oppose ISIS more than Assad, Turkey started bombing Kurdish groups in Turkey, Iraq and Syria, although the Kurds have been fighting against ISIS since its formation. Based on tensions between Turkey and the US about who is the primary enemy in Syria, Turkey doesn’t bomb ISIS.

While Assad has been losing ground to ISIS and the rebels, Russia intervenes on his behalf to bomb ISIS. On the ground, Russia has been bombing anti-Assad rebels including those backed by the US.

While Syrians are not much heard outside refugee camps, Americans, Europeans, Russians, Turks, Iranians, and Arabs hold meetings, agree and disagree, cooperate and coordinate, and coalesce and collide to find a solution for the “Syrian conflict”. According to the US Department of Defence, only the coalition airstrikes conducted in Syria reached 2,680 in 2015, from which 2,540 by the US and 140 by the rest of the coalition (Australia, Bahrain, Canada, France, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and UAE). The fact remains that almost no single Syrian citizen was left unaffected by the crisis, leaving Syria in a bloody war with no prospects of reconciliation in sight. So what is Syrian about the Syrian war? Perhaps, it is only the humanitarian catastrophe.

Comments Off on What is the Syrian War about?

The Middle East: Compliance with Authoritarian Exploitation

September 8th, 2015By Hakim Khatib

It is more often that we hear questions such as why do people comply with authoritarian exploitation? Why don’t they rebel, reform or change the status quo? Don’t they like to live in a democratic system? And many other questions. Well, People are more likely to wish for the end of authoritarian exploitation, but they lack the collective organization to do otherwise. Thus, the answer is more related to organizational issues than people’s aspirations. People are organizationally outmanoeuvred by ruling elites. Their rebellion against authoritarianism is more likely to serve dictators than populations.

Let’s take Egypt as an example: When people in Egypt were subjected to authoritarian rule since independence, they were controlled by military, police and political elites at the top (what can also be called the ruling blocs). The masses complied for over 60 years because they lacked collective organization to do otherwise. Any involvement of people in decision-making processes meant a loss of power to the regime in control. Therefore, the regime under Nasser, Sadat, Mubarak and most notably Al-Sisi created structures to guarantee their survival. Organization and reorganization of ideological, political, economic and military networks were enforced through coercion and imposition, even if some (mostly incapable to make fundamental change) rebelled and resisted.

However, by 2011, the collective incapacity to change the status quo in Egypt turned into a collective action resulting in mass protests on a huge scale. While these dynamics are dialectical and intertwined, a division of labour among the elites of the ruling blocs occurred in an attempt to counterbalance the collective action of the public. After the fall down of Mubarak, this collective action brought new elites to share power such as the Muslim brothers and Salafi parties. Due to the power struggle among political yet conflicting actors, it was necessary for the regime, namely the military and police forces, to outflank the organization of rival actors to remain in power.

The Muslim Brotherhood was later banned while Salafi parties were generally co-opted. This process was set up through conflict and cooperation to achieve the actors’ conflicting interests and goals taking the form of institutionalized laws and norms of social life. These shifts towards institutionalization of social life grant the ruling blocs a license to overlook the whole and reorganize power networks, keeping the bottom compliant. Any dissenting actors outside the institutionalized realm of social life become illegitimate and can be coercively outflanked. It is most obvious when we consider the crackdown against the Muslim Brotherhood and their protests against the military coup in 2013. Under the interim President Adli Mansour, the new coup elite passed a new protest law under the act 107 on 24 November 2013, by which the Ministry of Interior has the right to cancel, postpone or move any protest if serious intelligence suggests that the protestors might breach the law. This law was an implementation of the Constitutional Declaration issued on 08 July 2013, only five days after the deposal of the Islamist President Mohammad Morsi.

We can see dynamics of two configuration of power. The power over people by imposition and coercion, and that is coordination. And the power through people by sharing a collective understanding, and that is cooperation.

Due to the fact there has not been an elected parliament in Egypt since 2013, Al-Sisi enjoys the privilege of passing laws in the form of decrees and impose his will despite people’s resistance (preventing the bottom from sharing control). The assassination of Hisham Barakat in a car bomb on 29 June 2015, the Prosecution General of Egypt and the architect of thousands of prosecutions including controversial death sentences against Muslim Brotherhood followers can be easily, and actually already, politicized increasing Al-Sisi’s function in communication and interaction networks and granting him more organizational superiority over Egyptians.

At Barakat’s funeral, President Al-Sisi promised to amend the laws to make them responsive to the implementation of justice. “Under such circumstances, courts are useless and so are laws … The arm of justice is chained by the law,” said Al-Sisi promising to carry out any death or lifetime sentences against what he called “terrorists”. Consolidating his distributive power faster than any other dictator in the Middle East to impose his decisions over the Egyptian population and territory, Al-Sisi co-opted the judicial system as well as communications means. Succeeding in doing so, Al-Sisi controls the means of persuasion (institutionalized means) – the law, government loyal clergy and media – and the means of coercion – military, police and security forces.

Thus, people comply because they don’t know how or have the means to change power networks and organizations. They are embedded in organizational power structures, which they don’t control. They are bypassed and weakened by those at the top to make a significant change. This pattern doesn’t apply only to Egypt, but rather to the whole Middle East and North Africa region. It is not going well for Syrians nor Yemenis or Libyans. Revolutions often do not serve people’s aspirations. It seems it is too difficult to turn incapacity of people into a collective capacity for a long time.

As George Orwell said in his novel Nineteen Eighty-Four: “One does not establish a dictatorship in order to safeguard a revolution; one makes the revolution in order to establish the dictatorship.”

Comments Off on The Middle East: Compliance with Authoritarian Exploitation

The Struggle Over Ideological Power In The Middle East

August 26th, 2015By Hakim Khatib.

Using religious frameworks in political contestation and mobilisation processes has become more eminent in recent decades spiralling an intricate debate on the conceptualisation and implementation of such references in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region The contradiction, it is argued, mainly lies in the compromising nature of politics and the relatively dogmatic nature of religion. Accentuated by inaccurate media coverage and primordial analytical frameworks, it has become tempting to see religion as responsible for conflicts and underachievement in the MENA region

In the conventional sense, Islamic movements are often held responsible for incorporating religion in political processes. However, this is not always true as the nondemocratic states in the MENA region and elsewhere in the Muslim majority world had constantly attempted to control ideological power – Islamic religion and its organizations in this case – before Islamic movements even came to exist in the form we know today. The power struggle among political, yet conflicting actors over ideological power emerges from ideology’s distinctive form of social organization to legitimatize specific forms of authority and to solve contradictions in society.

By the end of 2010 and the beginning of 2011, uprisings across the Arab world overthrew long-lasting dictators, starting from Tunisia’s Zine Al-Abidine Ben Ali to Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak, Libya’s Muammar Al-Gaddafi and then Yemen’s Ali Abdullah Saleh. The uprisings caused an alteration of these countries’ political systems brining new overlapping, intertwining and intersecting networks of relations, by which new political actors and temporal dynamics have emerged.

Islamic factions, Salafists, Muslim brotherhood and their different variations, did not join the revolutionary momentum in Egypt from the very beginning, yet they played a major role after the “25 January revolution”. They won 351 seats from 498, around 70% of the Egyptian parliament. Whereas the conservative Islamic Freedom and Justice Party owned 45.7%, the ultra conservative Salafi Al-Noor Party owned only 23.6% , according to the Official Elections Portal of Egypt.

The Egyptian uprising was not per se a social revolution aimed at changing social structures in the Egyptian society, but rather a political one aimed at deposing a 30-year rule of dictatorship. Yet we can witness a shift in power balance altering the ideological power relations with other power organizations pushing Islamic factions to the top of the political pyramid to appoint a president – Mohammad Morsi – at one time and a shift back to elect a coup-installed regime under Abdulfattah Al-Sisi at another, who accordingly called for an Islamic revolution and reformation of religious discourse. How can we account for such dramatic trajectory divergences within less than five years?

Political contestation and mobilisation processes in the state of Egypt, or any other state for that matter, cannot be reduced to only ideological dimensions. Yet we can clearly observe a power struggle over ideological sources and organizations. Competeing actors engage in a constant struggle to control ideological power networks and sources in order legitimatize, mobilize, persuade, contest, control, lure, coerce and eliminate. Ideology, in other words, is a route to power.

This power struggle within military, security, political and religious institutions could pave the way for political instrumentalisation of Islam and trigger elimination and outbidding processes instead of democratic contestation. Elimination processes are more likely to create new network-like formations on the periphery and interstitial to official power networks relying on religion’s transcendence and socio-spatial extensive organisation.

When a division of labour between those who control security, the military, political institutions and those who control ideological networks occurs, new forms of relations follow. Seizure of power or change of its distribution is more likely to trigger these new forms of relations and perhaps networks, which are variable in their efficiency and capacity. This division of labour necessitates new emergent social relations to satisfy these actors’ needs. Somewhere at the beginning of this process, a space for political instrumentalization of Islam could befall because it constitutes a route to power.

Interstitial forms of extensive interactions, increasingly out of the official control emerge attracting more diffused masses of people, such as the Muslim Brotherhood’s followers, to become part of these interstitial networks, and thus, playing an emergent, yet distinctive form of social organisation to legitimatise specific forms of authority and to solve contradictions in society.

Ideology is a source of power exercised by an ideological network like other political, military and economic powers. However, ideological power can be more resilient if it is shared, divided, organized, reorganized and mobilized by other power networks. While ideological power enjoys a level of autonomy, which impels its networks to serve their own interests individually if possible, it can be stretched over other power organizations passing on a space for dangerously religious outbidding game and a cynical use of religion. That is why ideological power plays a decisive role in the power struggle in the Middle East. It is not the nature of the religion, but rather the usefulness of the ideological power for integrating, stabilising and mobilising social life.

Comments Off on The Struggle Over Ideological Power In The Middle East