October 27th, 2016

By Otaviano Canuto.

WASHINGTON, DC – Prospects for growth in global trade in 2016 and 2017 have been downgraded again. The World Trade Organization (WTO) nowexpects that trade this year will increase at its slowest pace since the post-2008 global recession. What is going on?

This is not purely a function of an anemic global economic recovery. After all, trade growth has typically outpaced GDP growth; in the years before the 2008 global financial crisis, the average increase was double that of output. But the ratio of trade growth to GDP growth has been falling since 2012, a trend that will culminate this year, with GDP growth outpacing trade growth for the first time in 15 years.

This reversal is driven partly by structural factors, including a plateau in the expansion of global value chains and a turning point in the process of structural transformation in China and other growth frontiers. The rising share of services in countries’ GDP likely implies further downward pressure on trade flows, given services’ lower trade propensity relative to manufactured goods.

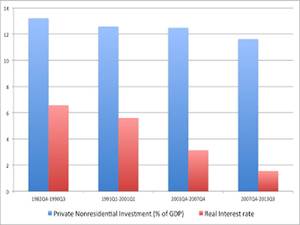

But not all of the forces undermining trade are so long-term. Crisis-related, temporary, and potentially reversible factors have also had an impact. For example, the economic hardship faced since 2008 by many eurozone countries, which have traditionally accounted for a substantial share of global trade, has discouraged consumption, hiring, and much more. The weak recovery of fixed investment in advanced economies has also undermined trade, because investment goods involve more cross-border exchange than consumer goods do.

Perhaps most risky, however, is the growing political backlash against free trade, reflected in a lack of progress in recent rounds of trade liberalization and the implementation of protectionist non-tariff trade barriers. Though such creeping protectionism has not yet had a significant quantitative impacton trade, its emergence has become a major source of concern amid rising anti-globalization sentiment in the advanced economies.

Today’s trade bashing is what happens when economic concerns – including stagnating median incomes and, in some countries, high unemployment rates – turn political. Viewing economic dissatisfaction as an opportunity to win support some shrewd politicians, particularly in the advanced economies, have been pointing the finger at the nebulous, threatening forces of “globalization.” Immigration and trade, they claim, are the cause of citizens’ economic insecurity.

Exhibit A is the current presidential campaign in the United States, which has placed more emphasis on trade than any such campaign in the country’s recent history. In a difficult political environment, both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump are proposing trade policies that depart from America’s long tradition of liberalization – with potentially dire economic implications.

Clinton, the Democratic candidate, now opposes the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade agreement that President Barack Obama’s administration negotiated with 11 other Pacific Rim countries and that is now awaiting ratification by the US Congress. She has also opposed conceding “market-economy status” to China, because it would make it harder to bring anti-dumping cases against the country. And she has advocated imposing countervailing duties on goods from countries that qualify as exchange-rate manipulators.

Trump, who has been among those leading the protectionist charge, takes these ideas much further. Like Clinton, he opposes the TPP and supports countervailing duties for currency manipulators. But he has also been particularly disparaging about Mexico and China, and is already calling for punitive US tariffs on both. Moreover, he promises to renegotiate and perhaps even abrogate existing trade agreements, alluding to the possibility of a US withdrawal from the WTO.

Clinton’s proposed measures would cause the US to lose out on some gains from trade, with consequences for the world economy. But the damage hardly compares to that which would be wrought by Trump’s proposals. After all, protectionist measures from the US would almost certainly spark reciprocal actions by its trade partners, potentially even spurring a trade war that compounds the economic pain for all.

As the Peterson Institute of International Economics highlighted last month, the negative impact would be felt most strongly by low-skill, low-income workers – precisely the people who are most convinced that less trade is a good thing. Worryingly, the report also shows that the US president has substantial leeway to adopt trade-curbing measures, without effective checks by Congress or the courts.

Obviously, there is a need to address the concerns that have fueled anti-globalization sentiment, politicians in the US and elsewhere should devise policies that will actually help their most vulnerable citizens. But demonizing trade is not the way to do it. On the contrary, as the experience in the 1930s showed, the easiest way to derail an already-feeble global economic recovery is to unleash a protectionist trade war.

Comments Off on Protectionist Creeps

September 8th, 2016

Much has changed since Fidel Castro arrived in Cuba on the Granma yacht in 1956.

Not long ago Cuba and the United States reopened embassies in Washington and Havana for the first time in decades, marking a crucial step towards the normalization of relations. Yet, while much attention will be placed on these international developments, perhaps the most decisive changes for Cuba will be domestic.

Crippled by a US trade embargo since the 1960s, Cuba’s underperforming centralized economy has long been propped up by a series of generous “sugar daddies”, from Soviet Russia to chavista Venezuela.

But Soviet support collapsed with the Berlin Wall, and Caracas is running out of sugar. Havana may not be willing to give up on the revolution, but it cannot afford the status-quo.

On an island known for obstinacy, something has got to give.

Watch The Crossroads Cuba Videos! Pt.1 The Crossroads Cuba

While many Cubans welcome change, any transition faces daunting challenges. Can Cuba liberalize commerce without inviting the staggering inequality endemic to Latin America? And can the state relinquish total power without sacrificing high quality, free public services?

Since assuming power from his brother Fidel in 2006, Raul Castro has gently edged Cuba towards a more market-based economy. The partial liberalization of private enterprise, home ownership and foreign direct investment are all suggestive of an economy in transition.

Cuba has taken similarly measured steps in the political realm, as evidenced by diplomatic normalization with the US. Raúl Castro has indicated that he will retire at the conclusion of his current term in 2018, ceding the Presidency to 55-year-old Vice President Miguel Díaz-Canel.

A preordained handover of power falls far short of true democracy, but it is representative of a broader transition from Cuba’s aging revolutionaries to a new guard of younger, ideological but reform-minded leaders.

There have even been indications that the party may be willing to ever-so-slowly loosen its grip on political power. The Cuban government tolerates a degree of political activism. For example, in last April’s municipal elections, the government permitted two non-party candidates to run for office.

Some online activism is also permitted: bloggers such as Harold Cárdenas Lema ofCuba Joven and Yoani Sanchez of 14ymedio have openly questioned Cuban governance, albeit from very different perspectives. However, limited internet on the island significantly curtails the number of Cubans who can access these blogs.

Of course, public displays of dissent — among many other freedoms of expression — are still firmly prohibited.

Still, something is changing here. Raúl’s reforms have been slow and halting, but they are likely irreversible. Cuba is clearly experiencing a transition. But a transition to what? What’s the end game here?

Watch The Crossroads Cuba Pt. 2 The Economy

The Cuban Economy: More Money, New Problems

Cuba’s fundamental economic problem is a lack of productivity, particularly from a bloated public sector. In response, the government has implemented reforms designed to shed jobs from public roles, with the expectation that people will join an inchoate private sector.

In agricultural centers, for example, the government has granted farmers increased control over what they harvest and where they can sell their produce. While they still must deliver a majority percentage of their output to the government, they can now sell the remainder at a market price.

More recently, “cuenta propistas“ have created opportunities in the cities for private enterprise and nonagricultural co-ops, from the barber, to the tire repairman, to certain craft and souvenir shops.

The Cuban government appears comfortable with these private operations, with entrepreneurs reporting generally unfettered activity. If anything, some private business owners claim, their taxes produce an important revenue stream for the government.

But with a 21st-century economy comes 21st-century problems. A key concern with Cuba’s economic reforms is that not all Cubans can take advantage of them, and some fear that inequality could be widening.

Productivity suffers from decades of underinvestment in infrastructure, equipment and machinery. This inattention is not surprising given the government’s hostility to larger private enterprise, as well as its own lack of funding. International direct investment and credit is also constrained by the US embargo.

With limited credit options, putting together the start-up capital for a private business is difficult for those without access to remittances or tourist revenue. The Afro-Cuban community, for example, may particularly lack access.

Another distorting factor in Cuba’s economy is the awkward dual-currency system. Two types of currency are currently traded in Cuba, one worth significantly more than the other

The Convertible Peso (CUC), used for example in the tourist industry, is worth more than the dollar. The National Peso (CUP), the currency of state salaries, is worth about four cents.

The result is a widening gap between those earning in CUC and those earning in CUP. Given the marked disparity, taxying a tourist across town can gross about as much as a state employee makes in two weeks. This creates incentives pushing Cubans into any activity that generates a cash flow in convertible currency regardless of productivity.

Havana hopes to unify the regimes in the coming months, but this would not close the gap between those with access to tourism revenue and remittances, and those on state salaries.

Watch The Crossroads Cuba Pt. 3 The Cuban Way & The USA

Diplomatic Relations Are Just a Start

Cuba’s complicated domestic transition requires far more support than simply changing the title of a building on the Malecon from “US Interest Section” to “US Embassy”.

Bringing Cuba into the global financial system and allowing the island become a member of development institutions such as the World Bank or the Inter-American Development Bank would be an important step to start closing the investment deficit. Also, given these organizations’ experience in transition economies, it could help the country with the needed structural and institutional reforms while keeping poverty and inequality in check.

Such multilaterals relations would be an important start, but the US could also play a critical role in helping Cuban economy through this period.

No policy from Washington could assist more Cubans — and more effectively undermine Havana’s hard line — then to end the US’s longstanding trade embargo against the island. The US Congress maintains the economic embargo presumably as a punishment for the government’s civil rights violations against the Cuban people.

The irony is that the Cuban people are the ones most severely punished by the policy.

The Cuban transition will not be easy, and it will not happen overnight. But it has an exponentially greater chance of success if the United States joins the large group of countries that already supports Cuba’s transition through constructive engagement rather than embargo.

The Crossroads Overtime: Otaviano Canuto speaks with Samuel George on Cuba’s Transition

Otaviano Canuto is an Executive Director at the International Monetary Fund. All opinions expressed here are his own and do not represent those of the IMF or of those governments he represents at the IMF Board

Samuel George is the Latin America Project Manager for the Bertelsmann Foundation, author of The Pacific Pumas, and creator of The Crossroadsvideo series.

Cornelius Fleischhaker is a junior professional associate at the World Bank and co-author of Five Steps to Kickstart Brazil. All opinions expressed here are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of the World Bank.

NOTE: The videos in this text are a project of Samuel George and the Bertelsmann Foundation and do not reflect the views of co-authors Otaviano Canuto, Cornelius Fleischhaker, or their institutions.

Comments Off on Not Your Grandpa’s Cuba: A New Light in the Caribbean

August 21st, 2016

By Otaviano Canuto.

Suriname is facing twin – external and fiscal – deficits that originated in the commodity price slump of recent years. In response, the Surinamese government started a four-pronged adjustment program in August 2015 to adapt to new circumstances.

Falling commodity prices led to multiple shocks on the Surinamese economy…

On the back of favorable commodity prices and appropriate domestic policies, the Surinamese economy grew at an average rate of 5% per year – amongst the highest in the Western Hemisphere – in the period 2003-2012. However, like other small commodity-dependent developing economies, Suriname has faced negative growth, external and fiscal deficits derived from falling commodity prices in recent years. The production of alumina, gold, and oil in the Surinamese economy accounted for 88% of exports and 40% government revenue in 2011. The global price decline of those commodities and the closure of the alumina refinery in late-2015 weighed drastically on economic growth (Chart 1).

Suriname’s current-account and fiscal balances have deteriorated (Chart 2). The fiscal balance moved from a small surplus in 2011, prior to the commodity price downfall, to a deficit of 8.8% of GDP last year, with the drop in government mineral revenue being responsible for 82% of that change (IMF, 2016). On the balance of payments side, the current account moved from a surplus of 5.7% of GDP in 2011 to a 15.6% deficit in 2015, although a larger part of the deterioration was due to a sharp increase in imports due to large investments in a new oil refinery and a new gold mine.

To facilitate the adjustment of the exchange rate to changing terms of trade, the government shifted from a pegged to a floating exchange rate regime in March 2016. To close the gap between the official and parallel exchange rates, the Central Bank of Suriname put in place a system of foreign exchange auctions (Chart 3 – left side). Similar to other commodity exporting countries, the local currency lost more than half of its value in dollars, and – together with some utility tariff hikes – was largely responsible for an inflationary spike (Chart 3 – right side).

… which are being faced with an IMF-supported four-pronged adjustment program

The government of Suriname took action to adjust to the commodity price shock and to lay the foundation to increase the economy’s resilience to future shocks. The government designed its adjustment effort in 2015 and began its implementation in August 2015 with an immediate strong fiscal adjustment. To finance the transition, soften the adjustment path, and facilitate the implementation of the far-reaching structural reforms that the government outlined in its program, the government approached the IMF and other international organizations in early-2016. These efforts led to an agreement on a Stand-By Arrangement in May 2016 with the IMF (2016) – the first program of Suriname since the country joined the IMF in April 1978. Success of this program is anchored on four pillars.

The reestablishment of fiscal sustainability was a key pillar of the policy response that started in August 2015: through a combination of expenditure cuts and revenue increases, the government reduced the fiscal deficit from an annualized 12.5% of GDP during January-July to 3.5% of GDP during August-December. A key element of the adjustment was the reduction in electricity tariff subsidies, with a 52%average increase in electricity tariffs in November 2015.

The government adjustment program that the IMF agreed to support incorporates additional measures to reduce the fiscal deficit further to 1.4% of GDP by 2018. In order to reach those targets, electricity subsidies and existing exemptions in income taxation for insurance companies will be scrapped; fuel and sales taxes will be hiked; a Value Added Tax and a vehicle tax will be introduced – the former by January 2018 and the latter in the second half of this year; the wage bill will be restrained; and contingency measures will stand ready to be deployed if necessary.

Critical to increase the resilience of government finances going forward are the reforms to strengthen the fiscal policy framework. These include modernization of public financial management, procurement, revenue administration, and treasury functions and the establishment of a sovereign wealth fund to minimize revenue fluctuations stemming from commodity price swings.

Following the Surinamese tradition to maintain a wide social protection network and protect the more vulnerable, the government will improve social cash transfer programs focused on the most vulnerable. By the same token, the reform of electricity prices eliminates one of the most regressive subsidies as 92 % of the subsidies used to accrue to the 10% largest consumers.

Rebuilding foreign reserves to harness confidence and stability is a second pillar of the government program. This is to come with the multilateral and limited commercial financing, fiscal adjustment, and an expected improvement in the external current account resulting from the flexible exchange rate and a strong increase in gold exports as the large investments of recent past come on-stream. The government projects (and the IMF agrees) that the current account will move from a deficit of 15.6% of GDP in 2015 to at least a zero balance in 2017-18. Foreign exchange reserves are, in turn, expected to reach 4 months of imports by end-2018 and stay there afterwards.

Increasing resilience through exchange rate, monetary, and financial policies is a third prong of the program. In order to avoid the propagation of the inflation shock that followed the exchange rate depreciation and other relative price adjustments, domestic liquidity conditions are being kept tight by necessity.

Finally, structural reforms for diversification and improving the business environment have also been included as a fourth pillar. Several areas where the business environment can be improved in a relatively shorter time span have already been identified, including enforcement of contracts, investor protection, registration of property, trade facilitation, exchange restrictions, access to finance and others. Tapping the agriculture sector potential can also be boosted with an improvement of public services concerning plant health, animal health, and fishery sustainable management

.

The government projects that the implementation of its adjustment and reform program will boost economic growth from -2% this year to 2.5% in 2017, taking into account the positive impact from the opening of a new gold mine, and to converge to a medium-term rate of 3%. Consumer price inflation will likely peak at 24% at end-2016 and decline to 6.1% by 2018.

That is a script in which Suriname can appropriately claim success in correcting its economic course after the drastic changes in the global environment. And the credit for the success should be given to the strong ownership of the Surinamese government, which designed the adjustment and reform program and began implementing it even before approaching the international community for its support, and to the Surinamese people, who understood the need for the adjustment and reform efforts to face the storm and have supported its implementation

Comments Off on Suriname: Facing the Storm with a Correction of Course

August 19th, 2016

By Otaviano Canuto.

2015 was the worst year for world trade since the aftermath of the global financial crisis, with figures exhibiting a decline of almost 14% in dollar value terms. In fact, world trade volumes have lagged behind GDP growth since the 2000s, a trend accentuated since the onset of the global financial crisis, whereas global trade increases took place at a higher pace than world GDP prior to the new millennium. Although some transitional – and therefore potentially reversible – explaining factors may be pointed out, some structural trends have also been at play. Given that trade has been a key driver of global growth, income convergence, and poverty reduction, concerns have been raised over whether the current directions of world trade lead towards a lesser development-boosting potential.

To what extent have recent developments in global trade been cyclical or structural?

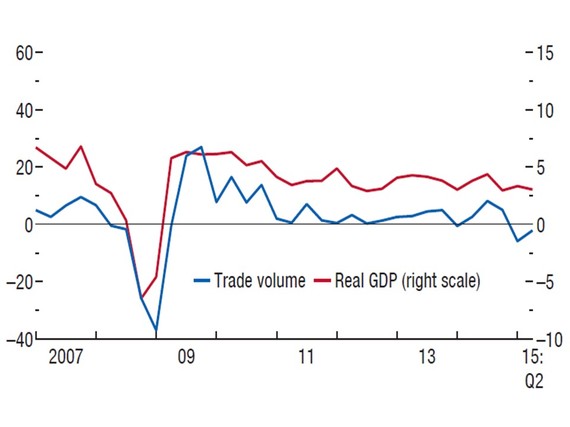

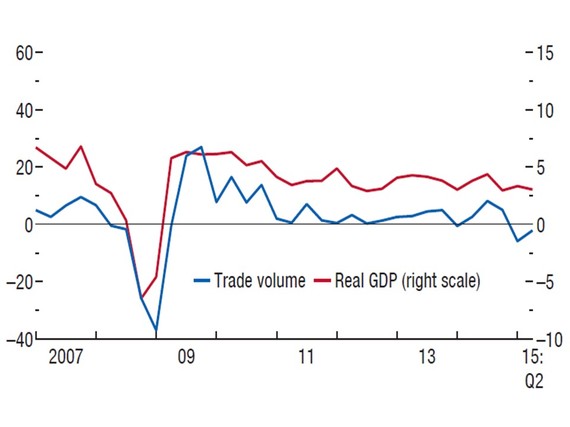

World trade suffered another disappointing year in 2015, experiencing a contraction in merchandise trade volumes during the first half and only a low recovery during the second half. (Figure 1). While last year’s trade performance can be associated to the on-going growth transition in China and its reflections on other non-advanced economies – see Constantinescu et al, Trade Turbulence, F&D, March 2016 – the fact is that last year’s performance came after a period since the 2000s in which world trade volumes have lagged behind GDP growth, a trend accentuated since the onset of the global financial crisis and in sharp contrast to global trade increases at a higher pace than world GDP prior to the new millennium.

Figure 1: World Merchandise Trade Volume

Source: Netherlands Bureau of Economic Policy, World Trade Monitor, December 2015

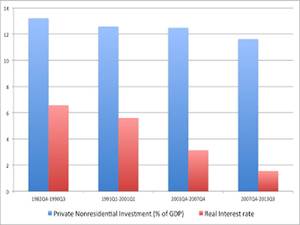

Economists have indicated some circumstantial factors to explain this post-GFC pattern (Dadush, 2015) (Didier et, 2015, p. 18). For instance, world GDP and trade figures would be reflecting the fact that the highly open-trade countries of the Eurozone have had a sub-par growth performance relative to the rest of the world. Furthermore, the weak recovery of fixed investments in advanced economies – Canuto (2014a) – has suppressed an important source of trade volume, given the higher-than-average cross-border exchanges that characterize such goods.

More disputed hypotheses have also been argued. More stringent capital requirements and financial regulations might be curbing the availability of trade finance. Additionally, rising “murky” trade-restrictive tax-cum-subsidy policy measures adopted in some key sectors by some countries may also have become more significant than usually perceived (Global Trade Alert 18, 2015).

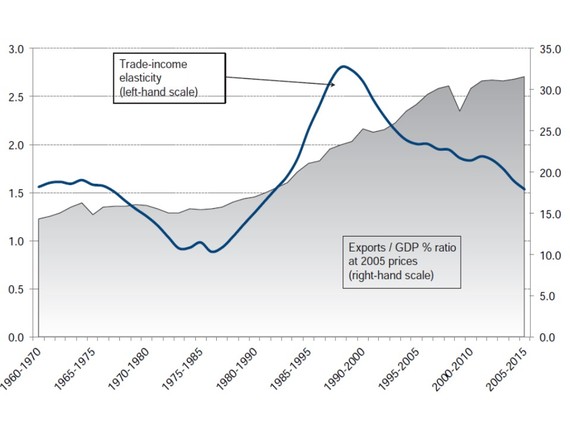

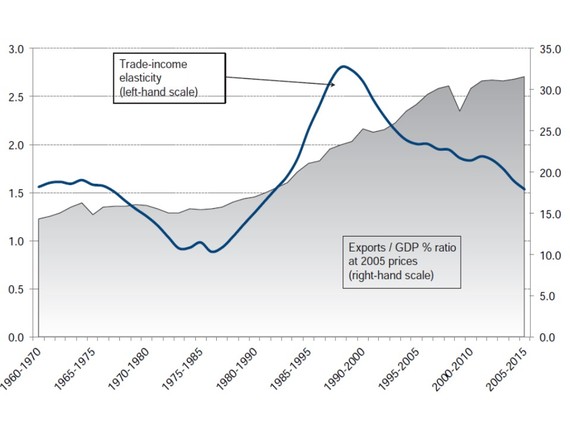

While those post-crisis factors have certainly played a role, some structural trends seem also to be at play. As suggested by Figure 2, after steadily increasing between the mid-1980s and the mid-2000s, the trade elasticity to GDP has lost steam (though it remained above one, thus implying that trade was still rising faster than GDP). After jumping in previous decades, the world’s exports-to-GDP ratio seems to have started to approach some plateau (or a “peak trade”). Since 2008, world trade has been rising slower than GDP at around 0.8:1, leading to a fall in the share of exports in global GDP. However, even if post-GFC factors were partially reversed, the presence of a long-term trajectory of trade elasticity displaying a slowdown already prior to the recent pattern would suggest no automatic return to the heyday.

Figure 2: Trade-income elasticity and Exports-GDP ratio – global economy

Source. Escaith and Miroudot, ch. 7 in Hoekman (2015)

Notes: Merchandise exports only; world GDP and trade at constant 2005 prices; dollar figures for GDP are converted from domestic currencies using official exchange rates. Long-term elasticity is based on 10-year rolling period from 1960-1970 to 2005-2015 (2015 is based on forecasts).

Hoekman (2015) brings a thorough examination of both “cyclical” (post-GFC) and “structural” hypotheses about the global trade slowdown. Regardless of the weight attributed to these factors in explaining recent developments, three processes stand out as relevant for the purpose of analyzing what lies ahead in terms of the link between global trade and development. Two of them were “transitional” – in the sense that they were “one shot” – the unfolding of which underpinned the extraordinary ascent of the global export-GDP ratio. The third one has evolved more gradually and will likely carry a significant transformative role ahead.

A major wave of vertical and spatial fragmentation of production has passed

The period from the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s was peculiar in several aspects. For one, these decades featured a process of economic reforms that aimed to remove barriers to trade, a multilateral trading system that reduced uncertainty for traders, and technological advances that reduced trade and communications costs. Combined, these trends ushered in years of sustained trade expansion. Average tariffs moved to well below ten percent, and in many countries a significant share of trade became duty-free. Advances in transport (such as containerized shipping) and information and communications technologies greatly reduced the cost of shipping goods and of managing complex production networks. Together these developments led to two major changes in the structure of global trade: (a) the vertical and spatial cross-border fragmentation of manufacturing into highly integrated “global production networks” or “global value chains” (GVCs); and (b) (to a lesser extent) the rise of services trade (Canuto, Dutz & Reis, ch. 3 in Canuto & Giugale, 2010) (Canuto, 2012).

The full establishment of cross-border GVCs intrinsically raises trade measured as gross flows of exports and imports relative to GDP, a value-added measure, because of “double counting” of the former – although the ratio of trade to GDP still increases even when trade is measured on a value-added basis (Canuto, 2013a). Given the then-prevailing technological state of arts in production processes, the policy and enabling-technology breakthroughs above mentioned sparked a powerful cycle of fragmentation, especially in manufacturing, with a corresponding cross-border spread of GVCs.

The re-shaping of the economic geography might have kept the pace with global trade impacts via further dislocation of fragments of GVCs, depending on the evolution of country locational attributes. Technological changes might also have altered optimal spatial configurations of the various manufacturing activities, as well as extended fragmentation to other sectors. This may well be the case ahead, as technologies and country policies keep evolving – some analysts point to a greater reliance on regional production networks, while others refer even to a potential reversal of GVCs because of 3D printing (“additive manufacturing”) (see references in the introduction of Hoekman (2015)).

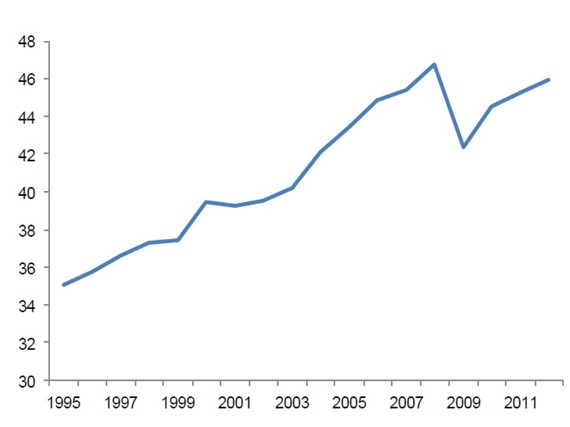

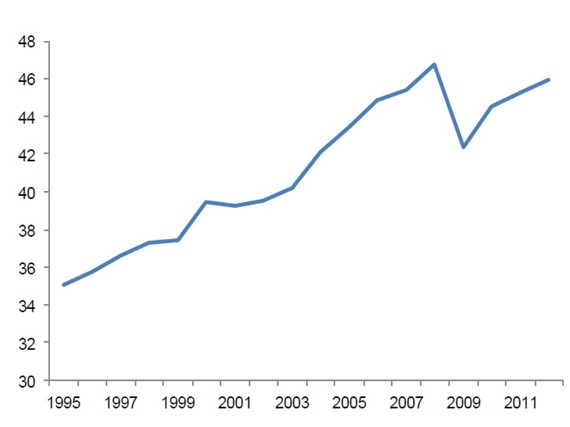

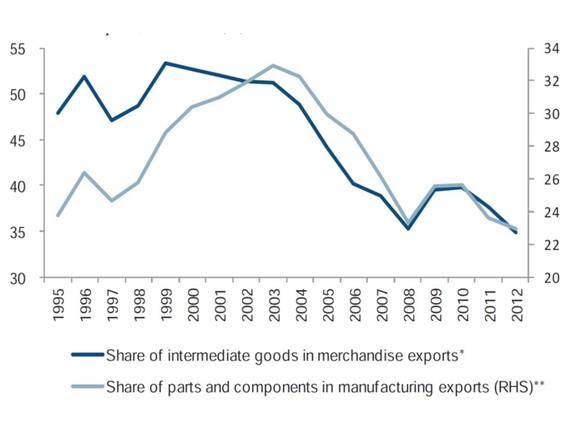

However, the wave of cross-border manufacturing fragmentation of mid-1980s through the mid-2000s was particularly intense and time-concentrated (Canuto, 2015a). Figure 3 – from Constantinescu et al (2015) – shows that the ratio of foreign value added to domestic value added in world gross exports increased by 2.5 percentage points from 2005 to 2012, after having risen by 8.4 percentage points from 1995 to 2005.

Figure 3: Ratio of Foreign Value Added to Domestic Value Added in World Gross Exports (%)

Source: Constantinescu et al (2015)

A major wave of trade-cum-structural-transformation has passed – with China as a special case

The wave of fragmentation of manufacturing activity benefited from the incorporation of large swaths of lower-wage workers from Asia and Eastern Europe into the global market economy (Canuto, 2015a). Conversely, the former facilitated a process of growth-cum-structural-transformation with substantial total factor productivity increases in these countries via transfer of population from low-value, low-productivity activities to the production of modern tradable goods, for which foreign trade was instrumental – with China as a special case both in terms of speed and magnitude (Canuto, 2013b) ((Gautier et al, ch. 5 in Hockman (2015)).

The transitional nature of such a lift of world trade relative to world real GDP, even as the latter grew substantially, stemmed from the inevitable tendency of both starting to rise more in line once the intense transformation approached completion. Its extraordinary intensity also reflected a peculiar – and transitory – combination of ultra-high investments-to-GDP and trade-surplus-to-GDP ratios in China with large current-account deficits of the U.S. (Canuto, 2009).

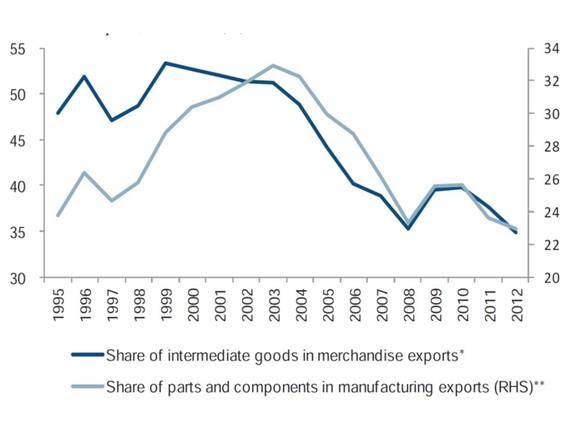

More recently, China has initiated a rebalancing toward a new growth pattern, one in which domestic consumption is to rise relative to investments and exports, while a drive toward consolidating local insertion in GVCs to move up the ladder of value added is also to take place. That rebalancing has been pointed out as one of the factors behind the recent global trade slowdown, given China’s weight in the world economy and a recent trend of “import substitution” as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4: China’s Share of Imports of Parts and Components in Exports of Merchandise

Source: (Constantinescu et al, ch. 2 in Hoekman (2015)

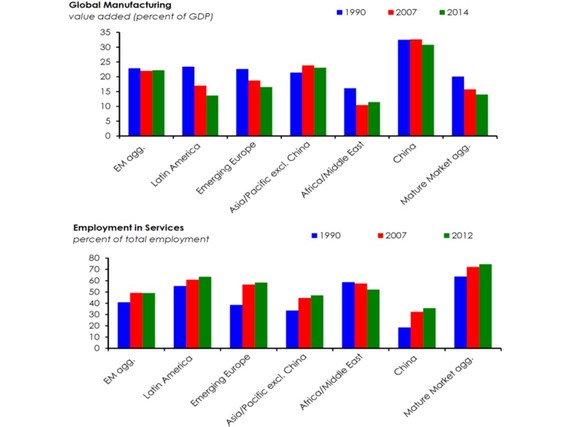

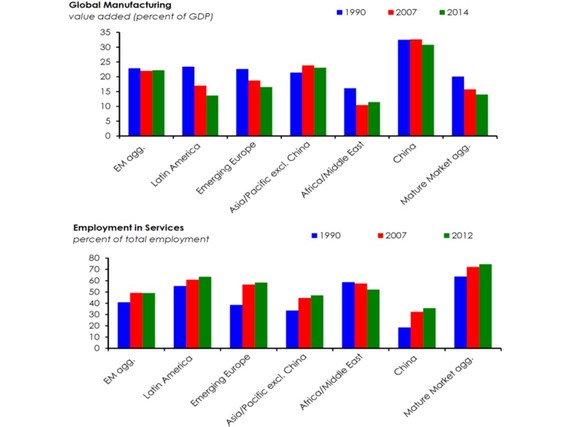

Advanced countries are becoming services economies

While both the GVCs’ rise and growth-cum-structural-transformation – especially in China – were taking place, with corresponding impacts on the landscape of foreign trade, advanced – or mature market – economies maintained a steady evolution toward becoming services economies – a trend maintained after the GFC. Lower GDP shares of the value added in manufacturing have accompanied rising shares of employment in services (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5: Global Manufacturing

Source: Institute of International Finance, “The rise of services – what it means for the global economy”, December 15, 2015

Figure 6: Employment in Services

Source: Institute of International Finance, “The rise of services – what it means for the global economy”, December 15, 2015

Both supply and demand factors explain such trends in advanced economies. On the supply side, beyond the higher pace of increases of productivity in manufacturing than in services (with correspondingly different rhythms of reduction in labor requisites), not only did the relative prices of manufactured goods fall, but a substantial part of local production was also off-shored as a result of GVCs and the incorporation of cheaper labor from areas previously out of the market economy world. On the demand side, one may point out both a higher income-elasticity of demand for services – reinforced by aging of the population – and to technology trends favoring “software” vis-à-vis “hardware” – or “intangible” relative to “tangible” assets – as leading to an increasing weight of services in GDP and employment (IIF, 2015).

Those evolutionary features of supply and demand would also be valid for emerging market and developing countries – even if, as suggested in the upper half of Figure 5, they were partially mitigated in China and other Asia/Pacific countries by sucking manufacturing activities from other emerging market and developing economies. In any case, given the state of current technological trajectories, rising shares of services throughout would imply an anti-trade bias, given a still higher trade-propensity of manufacturing.

IIF (2015) goes as far as to argue that this has already brought consequences for the global business cycle, rendering it less influenced by swings in manufacturing output, with shock transmission from advanced economies increasingly taking place via trade of services among themselves and more weakly to manufacturing-dependent emerging market and developing economies. This would be one of the factors behind the abrupt decline of the world trade elasticity and of the recent decoupling of growth between recovering advanced and decelerating emerging economies.

Has the window of opportunity of developing via trade integration narrowed?

World trade may well live through a new era of rise relative to GDP (Hoekman’s introduction in Hoekman (2015)): on-going technological trajectories may deepen the fragmentation and increase the tradability of services; new vintage trade agreements – including possible TPP and TTIP (Canuto, 2015b) – are giving special attention to restrictions on trade of services. In fact, the content of services in current foreign trade transactions has already been higher than what gross trade figures display (Canuto, 2014b).

Another question is what lies ahead in terms of growth opportunities for non-advanced economies through foreign trade given the evolution of the latter along the lines here described, one in which the factors that led to the “peak trade” seem to have exhausted, at least in the near future ahead. Trade has been a key driver of global growth, income convergence, and poverty reduction. Both developing countries and emerging market economies have benefited from opportunities to transfer technology from abroad and to undergo domestic structural transformation via trade integration in the last decades. One may thus understand why there has been some concern over whether the current pace and direction of world trade lead towards a lesser development-boosting potential.

The nature and height of domestic policy challenges have changed substantially in a three-fold way:

First, China is in a league of its own and its rebalancing-cum-upgrading will condition other emerging market and developing economies. If it lets low-skill labor-intensive manufacturing activities go, a new wave of further GVC dislocations may open opportunities for countries currently endowed with cheap and abundant labor. On the other hand, its densification of local parts of GVCs will represent a competitive challenge to medium-range manufactures produced in other middle-income countries. The net result will also depend on the leakages outward of its domestic demand as it rebalances toward a more consumption- and service-oriented economy.

Second, the directions taken by technological trajectories and aggregate demand in advanced economies seem to point toward a broad alteration of the balance of locational advantages for production fragments, decreasing the weight of labor costs and augmenting the relevance of local availability of other complementary intangible assets. A “double whammy” on production and exports of non-advanced economies may take place: a partial reversal of off-shoring and a slower growth of outlets for their typical exports.

Third, the bar, in terms of what it takes to countervail that double whammy (improvements of the local business environment and transaction costs, quality of economic governance and other conditions favorable to accumulation of intangible assets) has been raised. Nonetheless, provided that such bar is reached, the local provision of – embodied or disembodied – services complementary to those produced or used in advanced economies may flourish. This will be the case, e.g. of natural resource-rich countries that manage to develop related intangible assets in terms of applied-science capabilities.

The run-up to “peak trade” was one of primarily exploring complementarities within GVCs to substitute for existing producers. The post-peak trade era may well be one of building complementarities

Comments Off on What Happened to World Trade?

August 18th, 2016

By Otaviano Canuto.

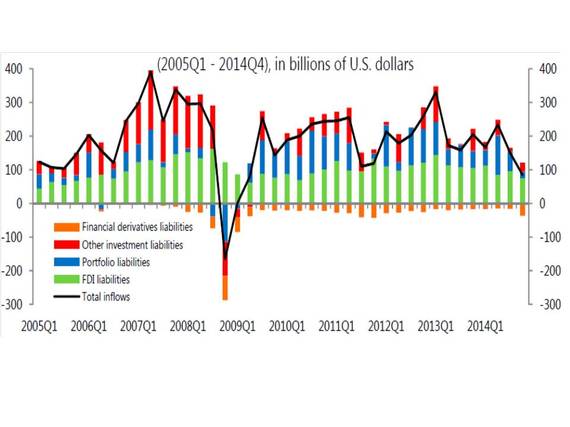

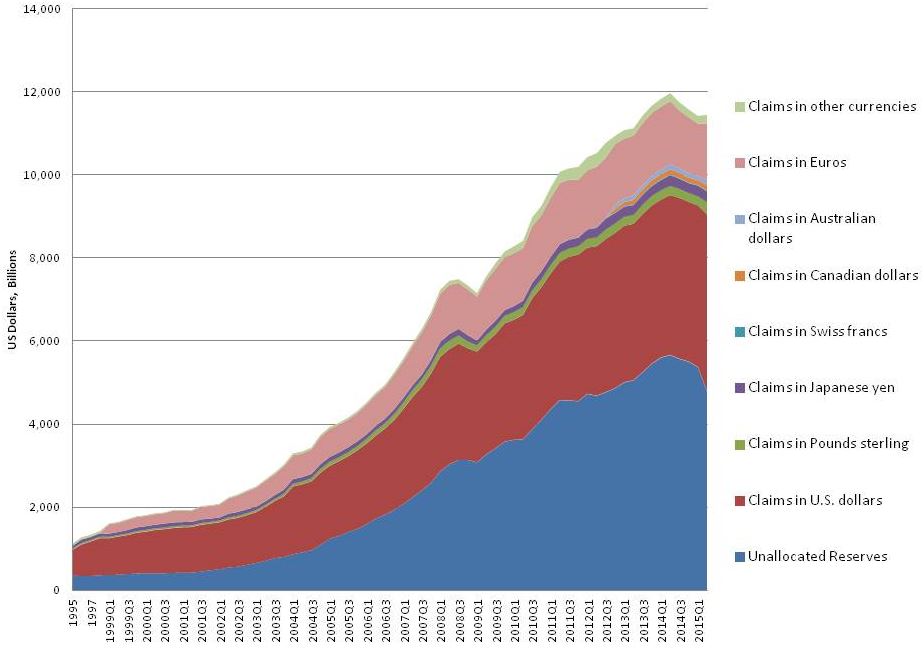

Emerging market economies (EM) as a special class of financial assets have recently been subject to two competing tales. On the one hand, there is evidence of continued financial deepening and further integration within the global financial system, while the offer of higher yields remains hard to find elsewhere. On the other hand, there are frequent bouts of fear of systemic unwinding of positions triggered by investors “exiting” EM that exhibit signs of weak or unclear macroeconomic foundations.

The upbeat tale finds support, e.g. in the fact that, taking advantage of the relatively benign environment of low interest rates and available global liquidity, many developing economies heretofore perceived as weak candidates have debuted in the sovereign debt markets attracting large volumes of foreign exchange (Gevorkyan and Kvangraven, 2016). More recently, what seemed at times to be a peak in sovereign borrowing has continuously been topped off as investors keep reaching for the yield and flows keep moving to EM. Last month, e.g. the IIF EM Portfolio Flows Tracker and Flows Alert reported a further strengthening of portfolio flows to emerging markets after the Brexit vote. Some geographical disparity has been showed – inflows to EM Asia and Latin America, modest outflows from EM Europe and Africa/Middle East – but non-resident portfolio flows to EM as a group climbed from $13.3 billion in June to $24.8 in July.

The downbeat story, in turn, has occasionally assumed the lead, combining episodes of overall rising risk aversion and groups of EM deemed to be in correspondingly more vulnerable positions. Like the “taper tantrum” in the summer of 2013 when the early references by the Fed to a future end of quantitative easing led to unwinding of positions on the then “fragile 5” EM (Canuto, 2013a), or when fears of a hard landing in China’s growth transition generated portfolio adjustments in other EM (Canuto, 2014a) (Canuto and Gevorkyan, 2016). While concerns about high levels of EM corporate debt leverage have remained at the forefront, easing of fears about China’s landing has more recently improved the risk-adjusted return prospects of EM as illustrated by flow figures of last month.

Changes in narrative have underlined financial ebb-and-flows

As the authors of this piece have highlighted in a recently released book – Gevorkyan and Canuto (2016) – those ebb-and-flows in EM financing have been accentuated by a change of narrative regarding EM structural strengths in the last few years. Not long ago, some analysts – including one of us (Canuto, 2010) – were anticipating a switchover in the growth engines of the global economy, with autonomous sources of growth in emerging and developing economies compensating for the drag of struggling advanced economies.

To be sure, the baseline scenario for the post-crisis “new normal” then outlined entailed slower global economic growth than during the pre-2008 boom. For major advanced economies, the financial crisis marked the end of a prolonged period of debt-financed domestic consumption, based on wealth effects derived from unsustainable asset-price overvaluation. Later on, attention came to be increasingly given to several hypotheses of “secular stagnation” in those economies (Canuto, 2014b).

However, 5 years of decreasing growth rates in the emerging market world – see Figure 1 – have thrown some cold shower on the enthusiasm about a switchover of locomotives. Even if there remains a growth differential – with some revival forecast by the IMF for next year – the fact is that the growth downward transition in China’s rebalancing, lower commodity prices, the exhaustion of domestic stimulus policies and the permanence of some structural flaws in most EM have led to a retrenchment of the expectation of a decoupling and even partial rescue of advanced economies by them.

It has become apparent that emerging-market enthusiasts underestimated at least two critical factors (Canuto, 2011; 2013b). First, emerging economies’ motivation to transform their growth models was weaker than expected. The global economic environment – characterized by massive amounts of liquidity and low interest rates stemming from unconventional monetary policy in advanced economies – led most emerging economies to use their policy space to build up existing drivers of growth, rather than develop new ones.

The second problem with the above mentioned emerging-economy forecasts was their failure to account for the vigor with which vested interests and other political forces would resist reform – a major oversight, given how uneven these countries’ reform efforts had been prior to 2008. The inevitable time lag between reforms and results has not helped matters.

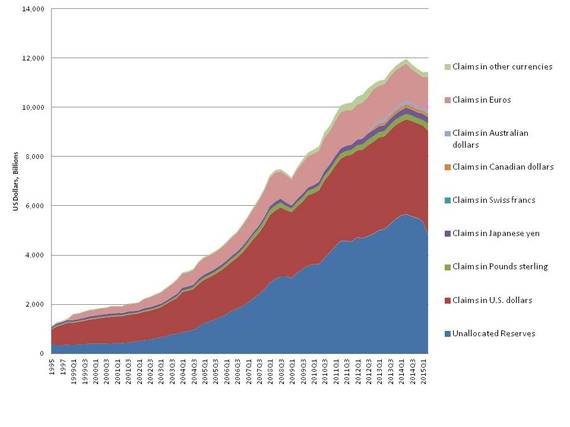

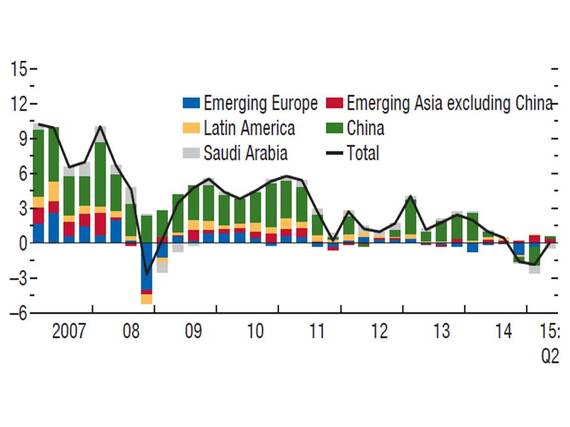

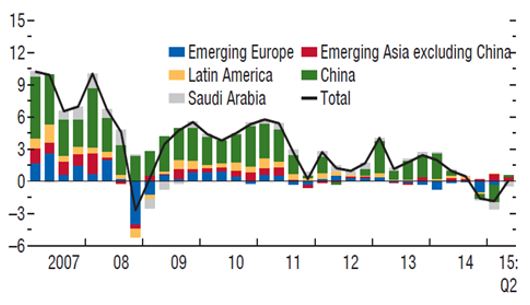

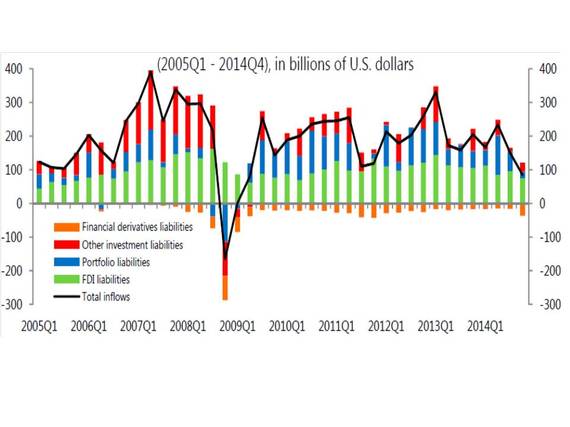

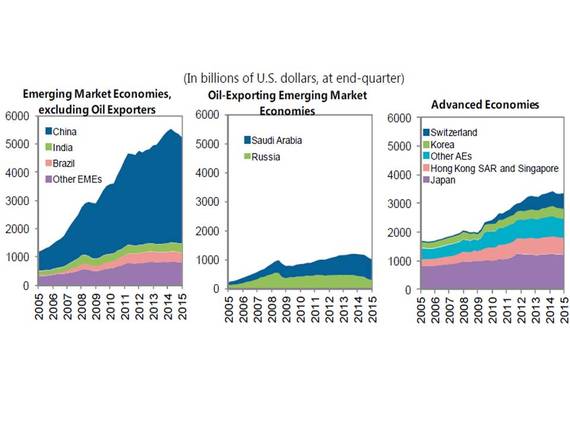

The most recent cycle of global financial flows often looks like to be running out of steam, in the wake of the phasing out of the US accommodative monetary policy stance, while concerns over the advanced economies’ recovery remain. The period of large-scale speculative financial flows and broad access to credit in emerging markets does not seem likely to return, despite ebbs and flows already mentioned. Even with occasional reversals of the downfall in foreign capital flows, emerging markets have already been coping with less benign external finance conditions (Figure 2).

Differentiation among emerging markets is coming to the fore

As approached in Gevorkyan and Canuto (2016), emerging markets as a class of economies exhibit a lot of heterogeneity in many regards. As highlighted by IIF (2015), notwithstanding a relatively clear dividing line between EMs and advanced economies, EMs are quite heterogeneous across various metrics. Their responses to shocks differ substantially according to their economic structures, such as dependence on external financing and on commodity exports.

Take for example the case of smaller, net importer, economies in transition in Eastern Europe and Former Soviet Union. There the institutional basis and economic structure are yet to evolve in a solid, established, form able to withstand unexpected and severe external pressures (see e.g. Gevorkyan, 2015 and Gevorkyan, 2011).

Taking all of the above together three critical points emerge as core features of medium term developments in the broader group of emerging markets, small countries included.

First, growth rates will remain sub-par across those heavy-weight EM dragged down by recent underperformance (e.g. Brazil, Russia), while China is expected to settle to growth rates much lower than in the period up to 2011 and India still needs structural reforms as a precondition to lift its growth pace to its potential.

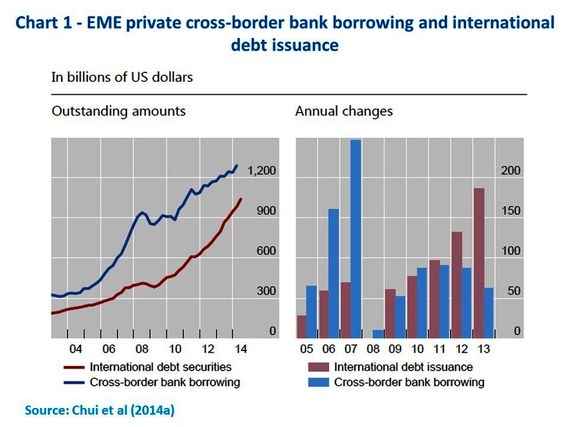

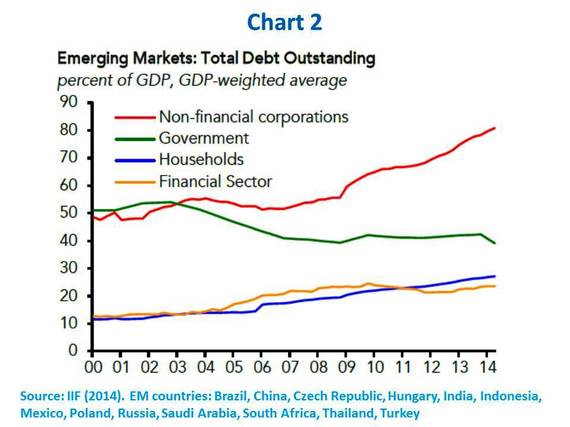

Second, EM will continue to capitalize on global low interest environment and abundant liquidity even as they implement structural adjustment policies and reforms, as well as while part of their non-financial corporates deal with the legacy of the excess debt leverage built until recently.

Third, as a result, a propensity to undergo periodic episodes of instability and volatility in global financial markets will persist. Get ready for a continuous dispute between the two financial tales about EM, as well as to increasing efforts of differentiation among their assets.

Comments Off on Tales of Emerging Markets

August 17th, 2016

By Otaviano Canuto.

The Chinese economy is rebalancing while softening its growth pace. China’s spillovers on the global economy have operated through trade, commodity prices, and financial channels. The global reach of the effects from China’s transition have recently been illustrated in risk scenarios simulated for Latin American and the Caribbean economies.

(1)

The Chinese economy is rebalancing while softening its growth pace…

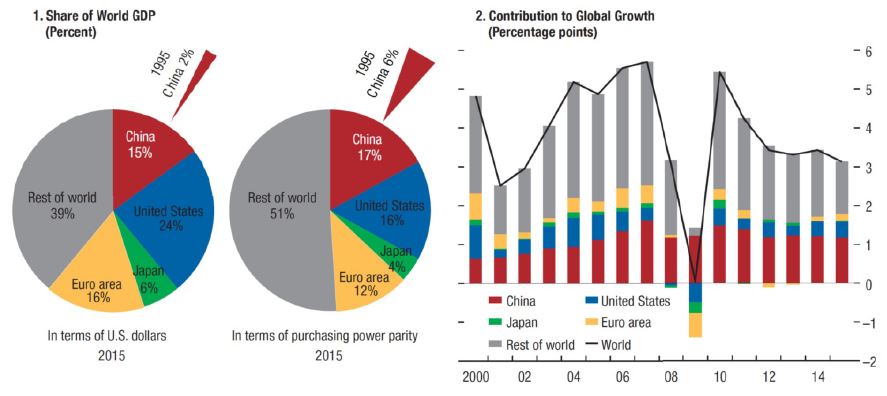

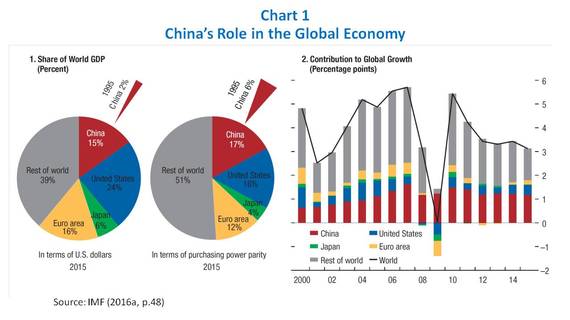

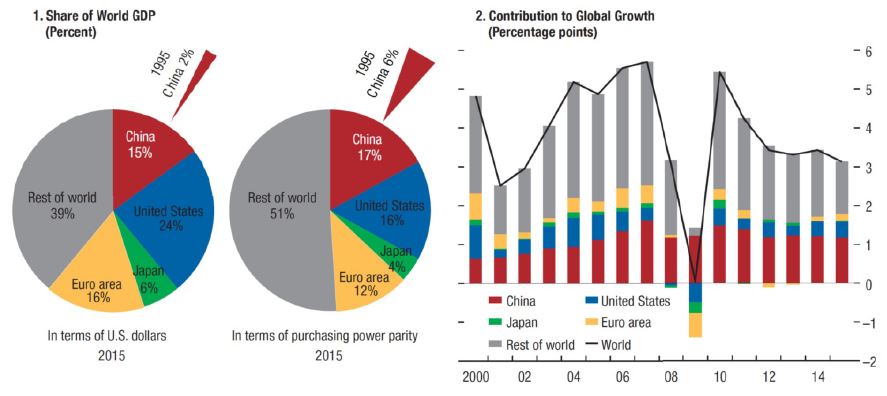

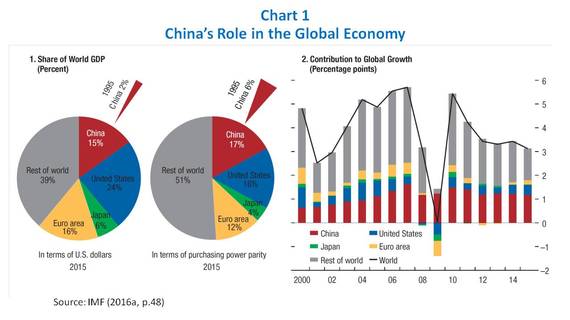

The weight of the Chinese economy in the global economy rose on its way to become the world’s second largest economy at market exchange rates and first in terms of purchasing power parity. As noted by the IMF (2016a, p.47), approximately one third of global growth during 2000-15 took place in China, while its exports increased from 3 percent to 9 percent as a share of world exports (Chart 1)

More recently, China’s economic growth has been morphing from one led by public investment and exports of manufactures, towards one where consumption and services are the main drivers (Canuto, 2013a) (IMF, 2016a). The new growth pattern entails lowering the GDP growth rates to levels that are more balanced and sustainable, based on rising purchasing power of its population and less dependent on huge trade deficits elsewhere in the global economy.

“China’s transition may, however, face bumps. First of all, some complex and time-consuming structural reforms will need to be implemented.”

China’s transition, on the other hand, may face bumps. First of all, some complex, time-consuming structural reforms will need to be implemented. The provision of public services must be widened, in order to convince households to raise their propensity to consume. The business environment will have to be reconfigured as a necessary step to make possible moving up the sophistication ladder in value chains and overcoming so-called “middle income traps” (Agenor, Canuto and Jelenic, 2012) (Agenor, Canuto and Jelenic, 2014). The existing universe of state-owned enterprise will also need to be reformed.

Furthermore, there is the legacy of corporate debt and excess capacity in former lead sectors that resulted as a consequence of policies implemented to avoid a hard landing in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. This legacy has been at the origin of occasional financial market jitters more recently. Fears of disorderly financial unraveling and abrupt exchange-rate depreciations have been behind episodes of capital outflows and loss of foreign reserves – Canuto and Gevorkyan (2016) – even if a more benign scenario has prevailed in recent months.

… leading to spillovers on the rest of the world…

In hindsight one now understands the core role played by China’s growth-cum-structural-change in the upswing and – in the last five years – downswing phases of the cycle during which developing and emerging market countries went from “switching over as global locomotives” – Canuto (2011) – to “getting lost in the transition” (Canuto, 2013b). Notwithstanding idiosyncratic, country-specific factors and policies underpinning the growth performance in those economies, they have all been impacted by the evolution of China’s economy – including the growth resilience exhibited by the latter after the global financial crisis, despite the cost of rising financial and capacity imbalances. The recent rebalancing of the Chinese economy has naturally also brought spillovers.

There are three channels through which those spillovers from China to the rest of the world have operated (IMF, 2016a, ch.2). First, there is trade as a direct channel. A faster-than-expected slowdown in imports and exports has reflected not only a deceleration in investment and manufacturing activities, but also a movement of densification of domestic value chains to the detriment of imports of intermediates or export-related inputs. China’s foreign trade was a key factor behind the world trade slowdown last year (Canuto, 2016).

Second, there are spillovers through commodity prices. The growth slowdown and rebalancing in the Chinese economy has been a major factor affecting the demand and prices of commodities. This is matched by developments on the supply side, following technological innovations and new capacities that emerged during the upswing phase of the super-cycle.

Third, there are the direct and indirect spillovers through financial channels. As bouts of uncertainty about the smoothness of China’s growth slowdown and policy changes often spark global risk aversion episodes, financial spillovers extend way beyond those economies that have developed deeper financial links with China. Interestingly, while the “taper tantrum” derived from U.S. monetary policy signals in the summer of 2013 – (Canuto, 2013c) – the turbulences in emerging markets’ exchange rates and capital flows in January 2014 could be traced to financial events in China (Canuto, 2014). This has also been the case in August 2015 and January this year.

… including Latin America and the Caribbean

Spillovers from China, as it undergoes its growth-slowdown-cum-rebalancing are illustrated in recent simulations of the impact on Latin America and the Caribbean as reported last month by the International Monetary Fund – IMF (2016b) – and the Inter-American Development Bank – IDB (2016).

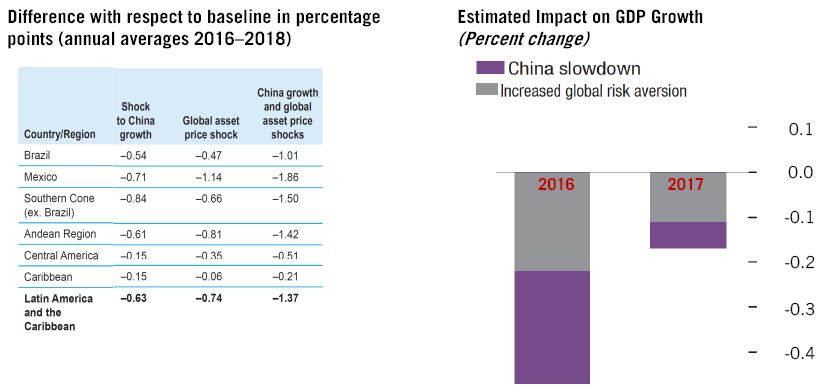

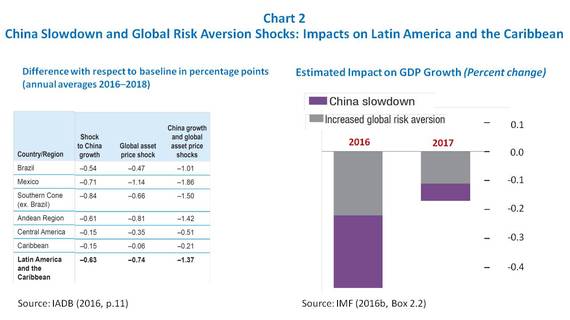

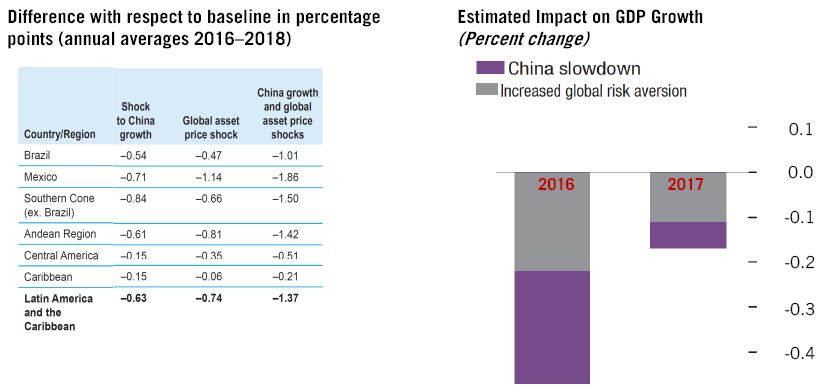

The IMF’s Regional Economic Outlook for the Western Hemisphere developed a risk scenario for Latin American and the Caribbean economies associated with a sudden bout of financial market turmoil in China. The simulation is based hypothetically on a wide set of the latter’s financial and real estate assets losing value, corporate risk premiums increasing, a new wave of capital outflows being triggered, the Renmimbi depreciating by about 15 percent, and falling investment and output. The supposed impact on the Chinese economy is a move of China’s growth 2 percentage points down relative to the IMF’s baseline in 2016 and 2017.

Such shock would affect the region not only through direct trade linkages, but also as a result of commodity prices being pulled downwards, with substantial declines in the case of minerals and fuels and smaller corrections in world food prices. As one would expect from the diversity of exposure to commodity prices in the region – Canuto (2015) – effects would tend to be highly heterogeneous notwithstanding their overall significance.

The IMF’s risk scenario also includes the effects of a rise in global risk aversion following the simulated financial turmoil in China, leading to a re-pricing of sovereign debt in the region. The overall results of both simulated stress factors are depicted on the right side of Chart 2 (IMF, 2016b, p.42):

“Based on model simulations, the cyclical slowdown in China could reduce growth in Latin America and the Caribbean by about ¼ percentage point in 2016 relative to the [IMF’s]World Economic Outlook baseline. In addition, an increase in sovereign risk premiums triggered by higher global risk aversion would cut growth by another ¼ percentage point. The overall impact declines in 2017 but is still negative (total of about 0.2 percentage point).”

The latest annual macroeconomic report of the Inter-American Development Bank also features risk scenarios for the region, that include the impact of a shock to China’s economic growth (of approximately 3 percent of GDP) and a global asset price shock (measured as a 10 percent fall in equity prices) – IDB (2016, p.9-10). The combined effect of both shocks would be something close to 1.4 percent per annum for 2015-2017 (Chart 2, left side). As illustrated in the IMF simulation, the impacts would be heterogeneous among countries but broadly significant.

China’s economic rise has also entailed increasing repercussions of its development in the rest of the world, including Latin America and the Caribbean. No wonder there is so much attention and hope for smoothness in China’s current economic rebalancing. After all, what happens in China does not stay in China…

Comments Off on IMF: China’s Spill-Overs on Latin America and the Caribbean

August 11th, 2016

By Otaviano Canuto.

While pro-cyclical fiscal policies – ie. expansionary fiscal policies in booms and contractionary fiscal stances in downturns – remain a common feature among developing countries, some countries have recently moved toward a less pro-cyclical fiscal stance, as a result of stronger institutions.

From theoretical and risk management points of view, a countercyclical fiscal policy can be useful for at least three compelling reasons (see Brahmbhatt & Canuto (2012) and World Bank (2014)). First, by leaning against the wind, governments can continue to provide goods and services and maintain public investment even in the event of a drop in public revenues. Second, in a downturn, a countercyclical fiscal policy can help governments increase social assistance and insurance to a large number of citizens affected by more adverse macroeconomic conditions. Third, as witnessed during the global financial crisis of 2008-09, a countercyclical fiscal policy can help countries stimulate the economy and cope better with the effects of a prolonged recession.

However, developing countries often orient government consumption and investment in the same direction as that of the cycle in general economic activity. In so doing, they amplify upswings and worsen recessions – what (Kaminsky, Reinhart, & Végh, 2004) termed as the “when it rains, it pours” phenomenon.

A simple inspection of Figure 1, which plots the value of fiscal stances in periods of expansion versus those registered in downturns, seems to lend partial support to the “when-it-rains-it-pours” phenomenon. Most of the countries in the upper and lower right quadrants of the chart are developing economies (in blue) and most importantly upper middle-income countries. In contrast, most of the high income countries (in red) appear on the upper and lower left quadrants with fiscal stances that largely contribute to long-term fiscal sustainability. However, the chart also confirms earlier findings in the literature showing that a number of developing countries have graduated from fiscal policy pro-cyclicality (c.f.,Frankel et al. (2013)).

These quadrants help categorize countries into four groups:

- Upper right quadrant: Those that exhibit pro-cyclical fiscal policies in both booms and downturns. Other things equal, such stance contributes to exacerbate output volatility. Not surprisingly, one finds many resource-rich economies in this category. In addition, many upper middle-income countries appear in prominently in that group.

- Upper left quadrant: Those that exhibit counter-cyclical fiscal policies in booms and pro-cyclical fiscal policies in downturns. Other things being equal, such fiscal behavior improves a country’s fiscal sustainability profile.

- Lower left quadrant: Those that exhibit counter-cyclical fiscal policies in both booms and downturns. Other things equal, such stance contributes to stabilize output around its long-term trend. Expectedly, most of high-income countries fall under this category.

- Lower right quadrant: Those that exhibit pro-cyclical fiscal policies in booms and counter-cyclical fiscal policies in downturns. Other things equal, such behavior deteriorates a country’s fiscal sustainability profile.

Figure 1

Source: Carneiro and Garrido (2015).

Some of the results may seem counter-intuitive but they actually uncover those countries that save for a rainy day, and those that let it pour when it rains.

For instance, one may be surprised to see Chile, a country that has earned a reputation of fiscal prudency and good overall macro management, in the fourth quadrant, which indicates risks to fiscal sustainability. As it turns out, Chile is, on average, for the period 1990-2011, moderately pro-cyclical in booms, and markedly anti-cyclical in downturns. Their ability to sustain a strong fiscal position arises from having a system of buoyant tax revenues and the great contribution of the private sector to economic activity, so the country is able to register solid, positive fiscal balances both in booms and recessions with marked improvements in its overall fiscal stance.

Compare this performance with that for Greece, for example, especially during the post-financial crisis period when it showed deteriorating fiscal balances, faster increase in expenditures relative to revenues, and poor economic performance, with an exacerbated contribution to volatility derived from a more pro-cyclical fiscal stance. With this, there is no doubt that Greece has yet to earn enough stars to join the same status as Chile’s.

As it turns out, many resource-rich countries remain clustered in the bottom right-hand quadrant. This is where things turn from moderate showers to a downpour too quickly. For this group of countries, in good times, all is well that ends well, but as soon as things turn sour so does their governments’ ability to lean against the wind.

Carneiro and Garrido (2015) have also found evidence in support of the idea that institutional quality is an important determinant of a country’s fiscal stance. This is an important result that suggests that efforts to graduate from fiscal policy pro-cyclicality need to be accompanied by policy reforms that seek to strengthen the ability of countries to save in good times to generate fiscal buffers that could be used in bad times. In that regard, initiatives such as the establishment of fiscal councils and the adoption of fiscal rules, the development of sound debt management strategies that reinforce fiscal discipline, and the strengthening of macro prudential regulations appear to be necessary conditions for graduation from pro-cyclicality.

Comments Off on When it comes to fiscal policy, it’s better to save for a rainy day than to let it pour

May 11th, 2016

By Otaviano Canuto.

The Chinese economy is rebalancing while softening its growth pace. China’s spillovers on the global economy have operated through trade, commodity prices, and financial channels. The global reach of the effects from China’s transition have recently been illustrated in risk scenarios simulated for Latin American and the Caribbean economies.

The Chinese economy is rebalancing while softening its growth pace…

The weight of the Chinese economy in the global economy rose on its way to become the world’s second largest economy at market exchange rates and first in terms of purchasing power parity. As noted by the IMF (2016a, p.47), approximately one third of global growth during 2000-15 took place in China, while its exports increased from 3 percent to 9 percent as a share of world exports (Chart 1)

More recently, China’s economic growth has been morphing from one led by public investment and exports of manufactures, towards one where consumption and services are the main drivers (Canuto, 2013a) (IMF, 2016a). The new growth pattern entails lowering the GDP growth rates to levels that are more balanced and sustainable, based on rising purchasing power of its population and less dependent on huge trade deficits elsewhere in the global economy.

China’s transition, on the other hand, may face bumps. First of all, some complex, time-consuming structural reforms will need to be implemented. The provision of public services must be widened, in order to convince households to raise their propensity to consume. The business environment will have to be reconfigured as a necessary step to make possible moving up the sophistication ladder in value chains and overcoming so-called “middle income traps” (Agenor, Canuto and Jelenic, 2012) (Agenor, Canuto and Jelenic, 2014). The existing universe of state-owned enterprise will also need to be reformed.

Furthermore, there is the legacy of corporate debt and excess capacity in former lead sectors that resulted as a consequence of policies implemented to avoid a hard landing in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. This legacy has been at the origin of occasional financial market jitters more recently. Fears of disorderly financial unraveling and abrupt exchange-rate depreciations have been behind episodes of capital outflows and loss of foreign reserves – Canuto and Gevorkyan (2016) – even if a more benign scenario has prevailed in recent months.

… leading to spillovers on the rest of the world…

In hindsight one now understands the core role played by China’s growth-cum-structural-change in the upswing and – in the last five years – downswing phases of the cycle during which developing and emerging market countries went from “switching over as global locomotives” – Canuto (2011) – to “getting lost in the transition” (Canuto, 2013b). Notwithstanding idiosyncratic, country-specific factors and policies underpinning the growth performance in those economies, they have all been impacted by the evolution of China’s economy – including the growth resilience exhibited by the latter after the global financial crisis, despite the cost of rising financial and capacity imbalances. The recent rebalancing of the Chinese economy has naturally also brought spillovers.

There are three channels through which those spillovers from China to the rest of the world have operated (IMF, 2016a, ch.2). First, there is trade as a direct channel. A faster-than-expected slowdown in imports and exports has reflected not only a deceleration in investment and manufacturing activities, but also a movement of densification of domestic value chains to the detriment of imports of intermediates or export-related inputs. China’s foreign trade was a key factor behind the world trade slowdown last year (Canuto, 2016).

Second, there are spillovers through commodity prices. The growth slowdown and rebalancing in the Chinese economy has been a major factor affecting the demand and prices of commodities. This is matched by developments on the supply side, following technological innovations and new capacities that emerged during the upswing phase of the super-cycle.

Third, there are the direct and indirect spillovers through financial channels. As bouts of uncertainty about the smoothness of China’s growth slowdown and policy changes often spark global risk aversion episodes, financial spillovers extend way beyond those economies that have developed deeper financial links with China. Interestingly, while the “taper tantrum” derived from U.S. monetary policy signals in the summer of 2013 – (Canuto, 2013c) – the turbulences in emerging markets’ exchange rates and capital flows in January 2014 could be traced to financial events in China (Canuto, 2014). This has also been the case in August 2015 and January this year.

… including Latin America and the Caribbean

Spillovers from China, as it undergoes its growth-slowdown-cum-rebalancing are illustrated in recent simulations of the impact on Latin America and the Caribbean as reported last month by the International Monetary Fund – IMF (2016b) – and the Inter-American Development Bank – (IDB, 2016).

The IMF’s Regional Economic Outlook for the Western Hemisphere developed a risk scenario for Latin American and the Caribbean economies associated with a sudden bout of financial market turmoil in China. The simulation is based hypothetically on a wide set of the latter’s financial and real estate assets losing value, corporate risk premiums increasing, a new wave of capital outflows being triggered, the Renmimbi depreciating by about 15 percent, and falling investment and output. The supposed impact on the Chinese economy is a move of China’s growth 2 percentage points down relative to the IMF’s baseline in 2016 and 2017.

Such shock would affect the region not only through direct trade linkages, but also as a result of commodity prices being pulled downwards, with substantial declines in the case of minerals and fuels and smaller corrections in world food prices. As one would expect from the diversity of exposure to commodity prices in the region – Canuto (2015) – effects would tend to be highly heterogeneous notwithstanding their overall significance.

The IMF’s risk scenario also includes the effects of a rise in global risk aversion following the simulated financial turmoil in China, leading to a re-pricing of sovereign debt in the region. The overall results of both simulated stress factors are depicted on the right side of Chart 2 (IMF, 2016b, p.42) :

Based on model simulations, the cyclical slowdown in China could reduce growth in Latin America and the Caribbean by about ¼ percentage point in 2016 relative to the [IMF’s]World Economic Outlook baseline. In addition, an increase in sovereign risk premiums triggered by higher global risk aversion would cut growth by another ¼ percentage point. The overall impact declines in 2017 but is still negative (total of about 0.2 percentage point).

The latest annual macroeconomic report of the Inter-American Development Bank also features risk scenarios for the region, that include the impact of a shock to China’s economic growth (of approximately 3 percent of GDP) and a global asset price shock (measured as a 10 percent fall in equity prices) – IDB (2016, p.9-10). The combined effect of both shocks would be something close to 1.4 percent per annum for 2015-2017 (Chart 2, left side). As in the IMF simulation, the impacts would be heterogeneous among countries but broadly significant.

China’s economic rise has also entailed increasing repercussions of its development in the rest of the world, including Latin America and the Caribbean. No wonder there is so much attention and hope for smoothness in China’s current economic rebalancing. After all, what happens in China does not stay in China…

Comments Off on China’s Spillovers On Latin America and the Caribbean

March 22nd, 2016

By Otaviano Canuto, Samuel George and Cornelius Fleischhaker.

For centuries, Latin America’s economies have revolved around exporting commodities – be it digging up minerals and hydrocarbons, planting soya or coffee, or taking advantage of what animals leave behind, the region has historically relied on shipping natural resources overseas.

Depending on the era, this could certainly be a lucrative endeavor, but commodity prices are notoriously fickle, and a focus on natural resources stunted the region’s efforts to build the manufacturing supply chains that have been instrumental in East Asia’s rapid industrialization.

In the post-World War II era, many Latin American countries attempted to address this commodity reliance by implementing import-substitution industrialization policies. In practice, this meant high tariffs to discourage imports, thus protecting domestic industry.

But without international competition, Latin American products often turned out over-priced and underwhelming. And when the region did try to liberalize in the 1990s, it did not work out so well.

As the 20th century gave way to the 21st, a number of Latin American countries returned to commodities, including agricultural products produced using increasingly sophisticated technologies. And they also went back to protectionist measures such as local content requirements aimed at supporting a domestic manufacturing sector struggling with currency appreciation.

This was a fine strategy while Chinese demand for raw materials pushed prices through the roof. But those prices have fallen in recent years, and the region faces a familiar challenge: How to move beyond commodity exports and towards successful integration into international trade networks.

TTIP & TPP – A Threat to Latin America?

As timing would have it, just as Latin American countries such as The Pacific Pumas (Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru) seek deeper integration into global trade, the world debates a series of mega trade deals.

How these deals will affect the region is a subject of a new Bertelsmann Foundation study, A Chain Reaction? Effects of Mega-Trade Deals on Latin America. So what did it find?

Let’s start with the Trans-Pacific Partnership – TPP – an agreement between mostly Asian and American countries—including Mexico, Chile, and Peru. According to the modeling Bertelsmann did with the Ifo Institute, Peru could be a big winner here. Their model suggests TPP could lead to a 2.4 percent increase in real income. Specifically, they see a 45 percent value-added boost to the metal sector. These results stem from the theory that once tariffs are lowered, Peruvian producers are more likely to refine commodities domestically and to export more valuable intermediate goods. In other words, instead of just digging it up and shipping it abroad, more steps towards a final product would be conducted in Peru.

For Chile and Mexico, however, TPP may not be such a big deal. Both countries already have deep trade agreements with major TPP partners, so our model suggests a new agreement might only have a marginal impact.

The Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership—TTIP—the proposed trade agreement between the US and EU, could pose more of a threat to Latin America. Many Latin American countries trade extensively with the US. If the US and EU come to an agreement, Latin America could lose its insider-access to US markets.

For example, Mexico, which has traded freely with the US since the implementation of NAFTA in 1994, conducts nearly 80 percent of its trade with Uncle Sam. Mexico would still retain certain advantages, such as proximity and cost of labor, but increased US trade with the EU could syphon-off a degree of trade. If the EU gets NAFTA-like access, Mexican exports to the US could fall by over five percent.

What about the countries that are not involved at all?

For example, Mercosur countries on the region’s Atlantic coast are not participants in TPP, TTIP, or any of the other mega-deals we analyzed.

The biggest of these countries, Brazil, is not a member in any of the mega-deals, and maintains relatively high tariffs. The model used in the report suggests that in terms of growth, the mega-deals will not have a major effect either way.

But they will effect Brazil’s export portfolio. With less relative access to markets participating in the mega-deals (such as the US, EU and Japan), Brazil could increasingly rely on trade with China—another outlying country—and one which does not need Brazil’s manufacturing goods. In our model, Brazil’s manufacturing sector would shrink in all scenarios, threatening to leave to country back where it started: digging things out of the earth and sending them abroad. (For more on the pacts’ effects on

Brazil, be sure to see Otaviano Canuto’s “Are Mega-Trade Agreements a Threat to Brazil?“.)

Dealing with Mega-Deals: Opportunities and Challenges

But all is not lost. The regional mega-deals currently under negotiation do provide an opportunity for countries to enhance their integration in global value chains. This is particularly relevant in Latin America, where cross-border connections have been largely absent due to the long shadow of import-substitution industrialization policies.

In many cases, remaining outside of transnational value chains resulted in loss of competitiveness of domestic industries, which lack access to low-cost inputs and the latest technology – see Canuto (2015) on the Brazilian case. Too often the response has been to increase trade barriers, further separating the domestic market from global integration. Consequently, the cost of being left out increases.

The new mega-deals come at a time when Latin American countries, especially the large economies, which have avoided integration, are in crisis. Now could be an opportunity to re-align with global trade.

For better or worse, TPP and TTIP could redefine global trade in the 21st century. At the moment, a Latin America perspective is largely lacking in the negotiation process; in TTIP, it is excluded by definition. But Latin American countries can move unilaterally to ensure that tariffs and regulations match what could become the new global standard.

Of course, alternatively, they could rebuild protective economic walls. But if they do, later on down the road, they just might have to pay for it.

Comments Off on TTIP & TPP – A Threat to Latin America?

February 12th, 2016

By Otaviano Canuto.

Trade has been a key driver of global growth, income convergence, and poverty reduction. Both developing countries and emerging market economies have benefited from opportunities to transfer technology from abroad and to undergo domestic structural transformation via trade integration in the last decades. Yet, more recently, concerns have been raised over whether the current pace and direction of world trade lead towards a lesser development-boosting potential.

What happened to world trade? Is it cyclical or structural?

World trade suffered another disappointing year in 2015, experiencing a contraction in merchandise trade during the first half and only low growth during the second half. This follows a similar pattern since the onset of the global financial crisis (GFC), in which world trade volumes have lagged behind GDP growth (Figure 1).

Figure 1

World Real GDP and Trade Volume

(Annualized quarterly percentage change)

Source: IMF, World Economic Outlook, October 2015.

Economists have indicated some circumstantial factors to explain this post-GFC pattern (Dadush, 2015) (Didier et, 2015, p.18). For instance, world GDP and trade figures would be reflecting the fact that the highly open-trade countries of the Eurozone have had a sub-par growth performance relative to the rest of the world. Furthermore, the weak recovery of fixed investments in advanced economies –Canuto (2014a) – has suppressed an important source of trade volume, given the higher-than-average cross-border exchanges that characterize such goods.

More disputed hypotheses have also been argued. More stringent capital requirements and financial regulations might be curbing the availability of trade finance. Additionally, rising “murky” trade-restrictive tax-cum-subsidy policy measures adopted in some key sectors by some countries may also have become more significant than usually perceived (Global Trade Alert 18, 2015).

While those post-crisis factors have certainly played a role, some structural trends seem also to be at play. As suggested by Figure 2, after steadily increasing between the mid-1980s and the mid-2000s, the trade elasticity to GDP has lost steam (though it remained above one, thus implying that trade was still rising faster than GDP). After jumping in previous decades, the world’s exports-to-GDP ratio seems to have started to approach some plateau (or a “peak trade”). Since 2008, world trade has been rising slower than GDP at around 0.8:1, leading to a fall in the share of exports in global GDP. However, even if post-GFC factors were partially reversed, the presence of a long-term trajectory of trade elasticity displaying a slowdown already prior to the recent pattern would suggest no automatic return to the heyday.

Figure 2

Trade-income elasticity and Exports-GDP ratio – global economy

Source: Escaith and Miroudot, ch. 7 in Hoekman (2015).

Notes: Merchandise exports only; world GDP and trade at constant 2005 prices; dollar figures for GDP are converted from domestic currencies using official exchange rates. Long-term elasticity is based on 10-year rolling period from 1960-1970 to 2005-2015 (2015 is based on forecasts).

Hoekman (2015) brings a thorough examination of both “cyclical” (post-GFC) and “structural” hypotheses about the global trade slowdown. Regardless of the weight attributed to these factors in explaining recent developments, three processes stand out as relevant for the purpose of analyzing what lies ahead in terms of the link between global trade and development. Two of them were “transitional” – in the sense that they were “one shot” – the unfolding of which occurred behind the extraordinary ascent of the global export-GDP ratio. The third one has evolved more gradually and will likely carry a significant transformative role ahead.

A major wave of vertical and spatial fragmentation of production has passed

The period from the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s was peculiar in several aspects. For one, these decades featured a process of economic reforms that aimed to remove barriers to trade, a multilateral trading system that reduced uncertainty for traders, and technological advances that reduced trade and communications costs. Combined, these trends ushered in years of sustained trade expansion. Average tariffs moved to well below ten percent, and in many countries a significant share of trade became duty-free. Advances in transport (such as containerized shipping) and information and communications technologies greatly reduced the cost of shipping goods and of managing complex production networks. Together these developments led to two major changes in the structure of global trade: (a) the vertical and spatial cross-border fragmentation of manufacturing into highly integrated “global production networks” or “global value chains” (GVCs); and (b) (to a lesser extent) the rise of services trade (Canuto, Dutz & Reis, ch. 3 in Canuto & Giugale, 2010) (Canuto, 2012).

The full establishment of cross-border GVCs intrinsically raises trade measured as gross flows of exports and imports relative to GDP, a value-added measure, because of “double counting” of the former – although the ratio of trade to GDP still increases even when trade is measured on a value-added basis (Canuto, 2013a). Given the then-prevailing technological state of arts in production processes, the policy and enabling-technology breakthroughs above mentioned sparked a powerful cycle of fragmentation, especially in manufacturing, with a corresponding cross-border spread of GVCs.

The re-shaping of the economic geography might have kept the pace with global trade impacts via further dislocation of fragments of GVCs, depending on the evolution of country locational attributes. Technological changes might also have altered optimal spatial configurations of the various manufacturing activities, as well as extended fragmentation to other sectors. This may well be the case ahead, as technologies and country policies keep evolving – some analysts point to a greater reliance on regional production networks, while others refer even to a potential reversal of GVCs because of 3D printing (“additive manufacturing”) (see references in the introduction of Hoekman (2015)).

However, the wave of cross-border manufacturing fragmentation of mid-1980s through the mid-2000s was particularly intense and time-concentrated (Canuto, 2015a). Figure 3 – from Constantinescu et al (2015) – shows that the ratio of foreign value added to domestic value added in world gross exports increased by 2.5 percentage points from 2005 to2012, after having risen by 8.4 percentage points from 1995 to 2005.

Figure 3

Ratio of Foreign Value Added to Domestic Value Added

in World Gross Exports (%)