April 17th, 2016

By Syed Qamar Afzal Rizvi.

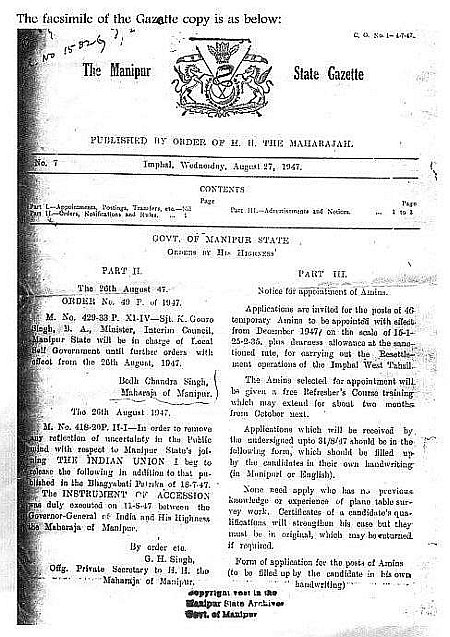

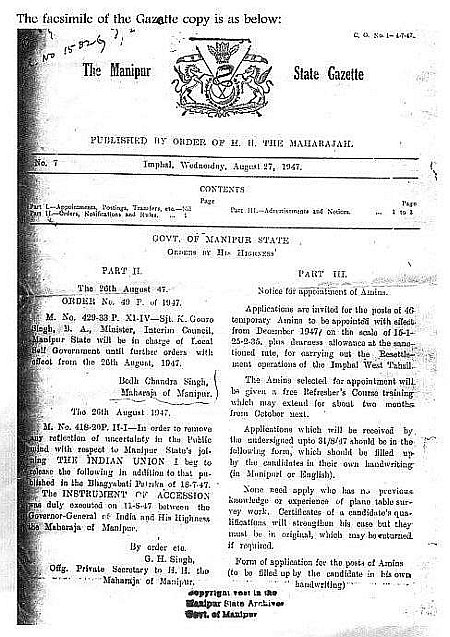

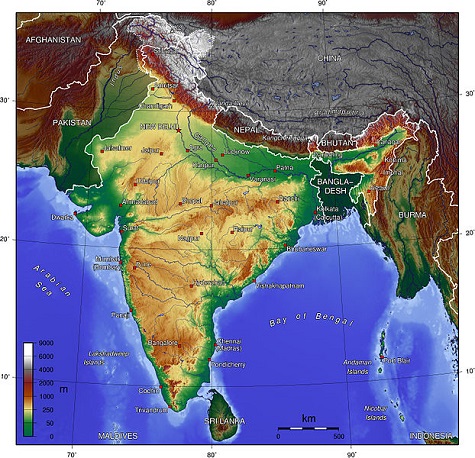

Pakistan upholds the right of the people of Jammu and Kashmir to self-determination in accordance with the resolutions of the United Nations Security Council. These resolutions of 1948 and 1949 provide for the holding of a free and impartial plebiscite for the determination of the future of the state by the people of Jammu and Kashmir. Pakistan continues to adhere to the UN resolutions. These resolutions are yet binding on India.

The UN’s mediatory role

The United Nations was involved in the conflict between Pakistan and India just months after the partition of British India. India brought the issue of Pakistani interference in Kashmir before the U.N. Security Council on January 1, 1948. Under article 35 of the U.N. charter, India alleged that Pakistan had assisted in the invasion of Kashmir by providing military equipment, training and supplies to the Pathan warriors. In response, Pakistan accused India of involvement in the massacres of Muslims in Kashmir, and denied any participation in the invasion.

Pakistan also raised question about the validity of the Maharaja’s accession to India (ii), and requested that the Security Council appoint a commission to secure a cease-fire, ensure withdrawal of outside forces, and conduct a plebiscite to determine Kashmir’s future (iii). The Security Council adopted a resolution establishing the United Nations Commission on India and Pakistan (UNCIP), to act as the mediating influence, and to undertake fact finding missions under article 34 of the Charter (iv). Shortly thereafter, the Security Council adopted another resolution in support of Kashmir’s right to self-determination, and in recognition for the need for a plebiscite (v). The plebiscite would be conducted under the supervision of an administrator appointed by the U.N. Secretary General and certified by UNCIP.

The resolution also called for withdrawal of armed Pakistani tribesmen and instructed India to reduce her forces. The Commission was informed that both countries had made the situation very complicated as Pakistani regular troops were already inside the borders of Kashmir and that the tribal invasion plus the Indian intervention had evolved into a larger state of war between India and Pakistan.

What about the instrument of accession?

A detailed examination into the legal order endorses the fact that India’s claim to Kashmir appears inconsistent with international law. Certainly, one may seriously question the Maharaja’s authority to sign the Instrument of Accession.

Pakistan argues that the prevailing international practice on recognition of state governments is based on the following three factors: first, the government’s actual control of the territory; second, the government’s enjoyment of the support and obedience of the majority of the population; third, the government’s ability to stake the claim that it has a reasonable expectation of staying in power.

The situation on the ground demonstrates that the Maharaja was hardly in control of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. In fact, almost all of Kashmir was under the control of the invading tribesmen and local rebels. The Maharaja held actual control over only parts of Jammu and Ladakh at the time that the treaty was signed. Moreover, Hari Singh was in flight from the state capital, Srinigar.

With regard to the Maharaja’s control over the local population, it is clear that he enjoyed no such control or support. Furthermore, the state’s armed forces were in total disarray after being thoroughly defeated by the invading forces and the local uprising. Finally, it is highly doubtful that the Maharaja could claim that his government had a reasonable chance of staying in power without Indian military intervention.

This assumption is substantiated by the Maharaja’s letter to the Government of India, in which he states that, “if my state has to be saved, immediate assistance must be available at Srinigar.” Therefore, if the Maharaja had no authority to sign the treaty, the Instrument of Accession can be considered without legal standing.

The legality of the Instrument of Accession may also be questioned on grounds that it was obtained under coercion. The International Court of Justice has stated that there “can be little doubt, as is implied in the Charter of the United Nations and recognized in Article 52 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, that under contemporary international law an agreement concluded under the threat or use of force is void.” As already stated, India’s military intervention in Kashmir was provisional upon the Maharaja’s signing of the Instrument of Accession. More importantly, however, the evidence suggests that Indian troops were pouring into Srinigar even before the Maharaja had signed the treaty. This fact would suggest that the treaty was signed under duress.

Finally, there is some doubt as to whether the treaty was ever signed. International law clearly states that every treaty entered into by a member of the United Nations must be registered with the Secretariat of the United Nations. The Instrument of Accession was neither presented to the United Nations nor to Pakistan.

While this does not void the treaty, it does mean that India cannot invoke the treaty before any organ of the United Nations. Moreover, further shedding doubt on the treaty’s validity, in 1995 Indian authorities claimed that the original copy of the treaty was either stolen or lost. Thus, an analysis of the circumstances surrounding the signing of the Instrument of Accession suggests that the accession of Kashmir to India was neither complete nor legal, as Delhi has vociferously contended for over fifty years. Kashmir may still legally be considered a disputed territory.

The core of the principle of self-determination

The principle of self-determination stipulates the right of every nation to be a sovereign territorial state. It affords to each population the right to choose which state it wishes to belong to, often by plebiscite. The principle of Self-Determination is commonly used to justify the aspirations of minority ethnic groups. The principle equally grants the right to reject sovereignty and join a larger multi-ethnic state. With regards to the Kashmir conflict, it is clear that Kashmir offered an ideological problem for both India and Pakistan. For Pakistan the Muslims of Kashmir had to be part of Pakistan under two nation theories (x), and for India, the failure of a Muslim majority state to survive within its system put under strain its secular vision. While considering the basic principle behind self-determination, as article 1(2) of the Charter of the United Nations 1945 states: ‘The purposes of the United Nations are…to develop friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples, and to take other appropriate measures to strengthen universal peace…’ we must also recognize that the doctrine of self-determination is also part of two more international human rights treaties: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (xi), and the International Covenant on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights (xii). Common article 1, paragraph 1 of these Covenants provides that: ‘All people have the rights of self-determination, by virtue of that right they freely determine their political states and freely determine their economic, social and cultural development.’

Pakistan’s argument

Pakistan argues that even if the Instrument of Accession is considered legal, India’s refusal to hold a plebiscite in Kashmir makes the accession incomplete. India, however, argues that its expressed “wish” to hold a plebiscite in Kashmir is amoral, not legal obligation. Pakistan, however, retorts that India’s obligation to hold a plebiscite in Kashmir arises out of India’s acceptance of the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP) resolutions of August 13, 1948.

This resolution contains proposals for holding a plebiscite in Kashmir which would allow the people to choose between accession to either Pakistan or to India. India asserts that the resolution states that the plebiscite will be held when a ceasefire is arranged and when Pakistan and India withdraw their troops from Kashmir. Neither of these conditions has been met.

But India’s position seems murky and dwindling considering the legal principle expressed in the Latin maxim nullus commodum capere potest de injuria sua propria (no man can take advantage of his own wrong). In the context of the Kashmir dispute, this means that India cannot frustrate attempts to create conditions ripe for a troop withdrawal and ceasefire in order to avoid carrying out its obligations to hold a plebiscite.

The evidence suggests that India was clearly at least as equally unwilling as Pakistan to withdraw troops from Kashmir. The London Economist stated that “the whole world can see that India, which claims the support of this majority [the Kashmiri people]…has been obstructing a holding of an internationally supervised plebis-cite.”

The Kashmir mediator’s findings

Owen Dixon, the United Nations Representative to the UNCIP, reported to the Security Council that, In the end, I became convinced that India’s agreement would never be obtained to demilitarization in any such form, or to provisions governing the period of the plebiscite of any such character, as would in my opinion permit the plebiscite being conducted in conditions sufficiently guarding against intimidation, and other forms of abuse by which the freedom and fairness of the plebiscite might be imperiled. In September 1950, Sir Owen Dixon, reported, that all means of settling the dispute over Kashmir, had been “exhausted” and suggested that India and Pakistan, be left to negotiate a settlement among themselves.

In this regard, India’s apparent efforts to obstruct the holding of a plebiscite in Kashmir stand in violation of international law. International law, however, clearly declares that states are obliged to treat all of their “peoples” equally and to insure that minorities are treated in a manner that does not threaten their culture or identity. Principle VII of the “Declaration on Principles” in the Helsinki Final Act pronounces that “the participating States on whose territories national minorities exist will respect the right of persons belonging to such minorities to equality before the law, will afford them the full opportunity for the actual enjoyment of Human Rights and fundamental freedoms and will, in this manner, protect their legitimate interests in this sphere.

The last attempt made by the UN

A legal solution based on arbitration was possible in 1957 when UNSC reaffirmed its earlier resolution that require the plebiscite. Gunnar Jarring was appointed by UN to mediator between India and Pakistan. On his proposal to demilitarization Pakistan Prime Minister Sir Feroz Khan Noon’s declared that his country was willing to withdraw its troops from Kashmir to meet India’s preconditions, the Security Council once again sent Frank Graham to the area. He tried to secure an agreement between India and Pakistan but India again rejected it. In March 1958, Graham submitted a report to the Security Council (UNSC) recommending that it arbitrates the dispute but as usual India rejected the proposal.

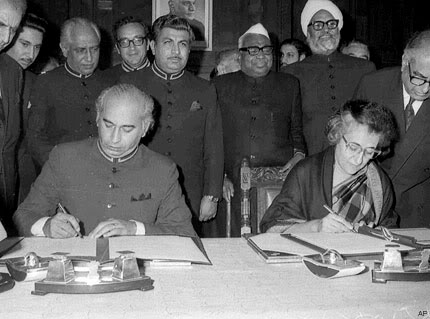

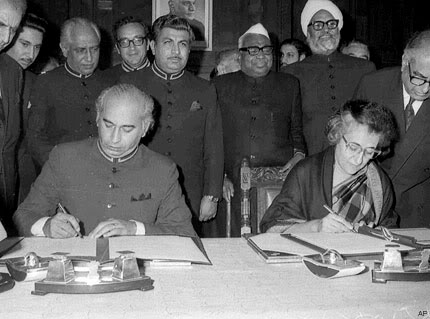

The notion of Simla agreement

The Simla Agreement does not prevent rising of Kashmir issue in the UN. It also does not restricts both countries for seeking the bilateral resolution only. Para 1 of Simla agreement specifically provides that the UN Charter “shall govern” relations between the parties. Para 1 (ii) providing for settlement of differences by peaceful means.

Articles 34 and 35 of the UN Charter specifically empower the Security Council to investigate any dispute independently or at the request of a member State. These provisions cannot be made subservient to any bilateral agreement.

According to Article 103 of UN Charter, member States obligations under the Charter primacy over obligations under a bilateral agreement. Presence of United Nations Military Observes Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) at the Line of Control in Kashmir is a clear evidence of UN’s involvement in the Kashmir issue.

India’s legal & moral responsibility

As a party to both the Geneva Convention and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, India is obliged to follow standards of human rights enshrined in these treaties. Pakistan declares that India has committed gross violations of human rights in Kashmir, thereby violating international law and justifying Kashmir’s right to self-determination. Those Indian thinkers or policy engineers who think that the principle of self determination of the people of Kashmir comes outside the colonial context and has no justification for UN’s mandatory role in Kashmir are absolutely in line up with the Israeli policy thinkers who also argue that Israel’s today enjoys the leverage of the doctrine of uti possidetis juris (0f 1810).They both are wrong and delusional in their thinking. And the notion- that the UN’s resolutions on Kashmir are obsolete-holds no justification. The fact of the matter is that the UN Charter upholds the right of self- determination without compromising the political expediencies. It is why there are manifold UN’s resolutions on both Palestine and Kashmir.

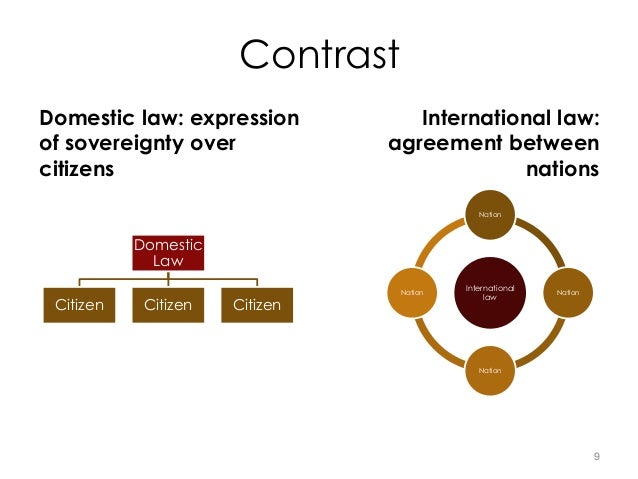

The argument of ‘shared & international responsibility’ in international law

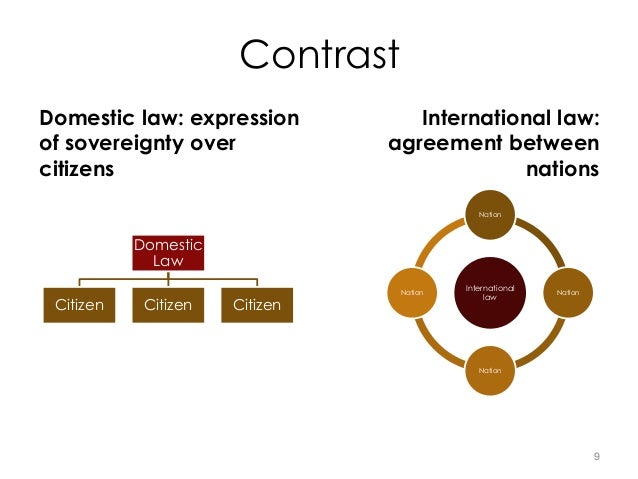

International law carries out the attribution of wrongful conduct pursuant to the agency theory, which operates en lieu of causation. The absence of causal analysis from the determination of internationally wrongful acts is the result of consistent State practice, based on a clear distinction between the national and international legal orders.

International responsibility is not domestic liability writ large; it is international accountability of international actors in the international community. The differences that international responsibility bears with domestic legal orders respond to the legal articulation of an international system of rules, distinct from the legal orders of the sovereign subjects it addresses. Given the logic of this argument of international law , the UNSC as well as India have to fulfill their ascribed roles of international responsibility vis-à-vis Kashmir dispute that causes great concern in international community.

Kashmir is an unfinished agenda of the partition of subcontinent. A solution to Kashmir is absolutely crucial to ensuring the integrity of both international law and international security on the subcontinent.

Comments Off on International law upholds Pakistan’s Kashmir argument

April 14th, 2016

By Qamar Syed.

This week’s conference in Geneva(April 7-8) was organized to help build political momentum in the run-up to the 10th anniversary of the strategy and its review and to carry forward the debate that the General Assembly had in January on finding more areas of convergence on preventing violent extremism.

Violent extremism is an affront to the very purposes and principles of the United Nations, the Head of the world body’s Geneva headquarters said, urging government delegations and experts gathered there to endorse the comprehensive approach needed to proactively address the drivers of the scourge, including through support of the Secretary-General’s action plan on the issue.

“[Violent extremism] not only challenges international peace and security, but undermines the crucial work that Member States and the UN family are conducting to uphold human rights, take humanitarian action and promote sustainable development, said Michael Møller, Director-General of the United Nations Office at Geneva (UNOG).

Ban Ki Moon’s indoctrination

The Secretary-General has been of the view that no cause or grievance can justify the “unspeakable horrors” that terrorist groups are carrying out against innocent people, the majority of whom are Muslim. Women and girls, he added, are particularly subject to systemic abuses – rape, kidnapping, forced marriage and sexual slavery.

“These extremists are pursuing a deliberate strategy of shock and awe – beheadings, burnings, and snuff films designed to polarize and terrorize, and provoke and divide us,” the UN chief added, commending UN Member States for their political will to defeat terrorist groups and at the same time, urging them to stay “mindful of the pitfalls.”

“Many years of our experience have proven that short-sighted policies, failed leadership and an utter disregard for human dignity and human rights have causes tremendous frustration and anger on the part of people who we serve,” the UN chief said.

He outlined what he called four imperatives to deal with violent extremism. First, the world must look for motivations behind such ideologies and conflict. While this has proven over and over again to be a “notoriously difficult exercise,” it is vital to realize that poisonous ideologies do not emerge from thin air – oppression, corruption and injustice fuels extremism and violence.

“Extremist leaders cultivate the alienation that festers. They themselves are pretenders, criminals, gangsters, thugs on the farthest fringes of the faiths they claim to represent. Yet they prey on disaffected young people without jobs or even a sense of belonging where they were born. And they exploit social media to boost their ranks and make fear go viral,” Mr. Ban said.

Violent extremism affects all the 4 core areas (peace and security, humanitarian assistance, human rights and development) of the work of the UN, so all parts of the UN System have to work together on this issue.

The UN’s proposed plan of action

The action plan is based on five interrelated points, Mr. Ban Ki Moon said, namely prevention, national ownership, international cooperation, UN support and united action.

Security and military responses sometimes have proven to be counter-productive, and there is a need to address the drivers of violent extremism, he noted.

“There is no single pathway, and no complex algorithm that can unlock the secrets of who turns to violent extremism,” he stated. “But we know that violent extremism flourishes when aspirations for inclusion are frustrated, marginalized groups linger on the sidelines of societies, political space shrinks, human rights are abused and when too many people – especially young people – lack prospects and meaning in their lives.”

The Plan emphasizes conflict prevention, conflict resolution and political solutions, and urges full implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), as that will address many of the socio-economic drivers of violent extremism.

The Plan offers a menu of recommendations for Member States to forge their own national action plans, which should use an “all-of-Government” approach and engage “all-of-society” to be effective. No country or region alone can address the threat of violent extremism, he said, stressing the need for a dynamic, coherent and multi-dimensional response from the entire international community.

He pledged to leverage the universal membership and the convening power of the UN to further strengthen international cooperation at the national, regional and global levels, noting that he plans to create a UN system-wide high-level action group to spearhead the implementation of the Plan at both the Headquarters and field levels.

“We will not be successful unless we can harness the idealism, creativity and energy of 1.8 billion young people around the world,” he said, calling for a global partnership to prevent violent extremism. “I have no doubt that we will succeed if we are united in action,” he concluded.

UN agencies and other international organizations in Geneva work at the crossroads of peace, rights and wellbeing and are at the core of implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. “Providing sustainable development opportunities, reducing inequalities, safeguarding human rights and providing a hub for mediation and peace negotiations, help to create a context and change realities on the ground that are better suited to resist extremism,” he said.

Further, the Secretary-General’s Plan of Action provides an important framework to address the issue at hand. The Plan has been welcomed by the General Assembly, showing the positive commitment of the international community to unite and act against this threat.

“To put the Plan into action, contributions from all actors are needed. The Secretary-General has put forward a multidimensional and ‘All of UN’ approach, explained Mr. Møller. Additionally, while recognizing the importance of the principle of national ownership to effectively address violent extremism, the Plan calls on all relevant actors – governments, civil society, academia, community and religious leaders – to act in unison through an “all-of-Government” and “all-of-Society” approach.

A backdrop to the UN’s strategy: uniting against terrorism

A real strategy is more than simply a list of laudable goals or an observation of the obvious. To say that we seek to prevent future acts of terrorism and that this world seeks better responses in the event of a terrorist attack does not amount to a strategy. Only when it guides the international community in the accomplishment of UN’s goals is a strategy worthy of its name. In order to unite against terrorism, the global community needs an operational strategy that will enable all nations together to counter terrorism.

It has been against this background that in 2006, the United Nations under the auspices of Secretary General Kofi Annan formulated the recommendations for a strategy seek to both guide and unite the global community by emphasizing operational elements of dissuasion, denial, deterrence, development of state capacity and defence of human rights. What is common to all of these elements is the indispensability of the rule of law, nationally and internationally, in countering the threat of terrorism. .

Inherent to the rule of law is the defence of human rights — a core value of the United Nations and a fundamental pillar of our work. Effective counter-terrorism measures and the protection of human rights are not conflicting goals, but complementary and mutually reinforcing ones.

Accordingly, the defence of human rights is essential to the fulfilment of all aspects of a counter-terrorism strategy. The central role of human rights is therefore highlighted in every substantive section of UN’s observatory report, in addition to a section on human rights per se. Victims of terrorist acts are denied their most fundamental human rights.

Accordingly, a counter-terrorism strategy must emphasize the victims and promote their rights. In addition, implementing a global strategy that relies in part on dissuasion, is firmly grounded in human rights and the rule of law, and gives focus to victims depends on the active participation and leadership of civil society. Therefore, there is no doubt that international civil society can play in promoting a truly global strategy against terrorism.

The role played by the Council of Europe?

The United Nations Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy was adopted in September 2006 (A/RES/60/288). The UN Security Council has adopted a number of resolutions to promote the implementation of the Strategy, amongst them two mandatory “Chapter VII” Resolutions, 1373 (2001) and 2178 (2014).

As a regional organisation, the Council of Europe is committed to facilitating the implementation the Strategy and the Security Council Resolutions. It does this by providing a forum for discussing and adopting regional standards and best practice and by providing assistance to its member states in improving their capacity to prevent and combat terrorism, to address the conditions conducive to the spread of terrorism and to ensure respect for Human Rights and the rule of law in the fight against terrorism.

The Council of Europe contributes to the biennial reports (2014 report A/68/841) of the UN Secretary General on the activities of the UN System in implementing the Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy and participates in the UN General Assembly reviews of the Strategy. The role played by the Council of Europe serves to be a model of paragon for other regional organizations to positively join this global cause against terrorism.

Countering violent extremism & UN’s challenges

The emergence of the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) has created a greater sense of urgency for many governments as they grapple with the outpouring of refugees; with national security concerns raised by the prospective return of foreign fighters; and the exacerbation of existing conflicts by the ideology and tactics exported by the group. While emerging from al-Qaeda, ISIL has premised its legitimacy on purporting to offer a just and effective state that ostensibly addresses many of the grievances of citizens in the region.

In its communications, ISIL does not portray itself as a secretive terrorist group, but rather as a welcoming state that seeks to offer its citizens healthcare, basic services, protection and infrastructure. In many ways, much of its recruitment material speaks the language of state-building and development, although it does not shy away from the use of brutality to assert itself.

The need to understand and respond to the development and security deficits that drive ISIL’s support and assumed legitimacy is therefore critical. Findings about the localised and individualised nature of drivers of violent extremism indicate that many of the UN’s core goals on preventing conflict and promoting human rights and sustainable development can be key to reducing the appeal of terrorism.

This was underscored in January 2015 when the UN Security Council described the relationship between security and development as “closely interlinked and mutually reinforcing and key to attaining sustainable peace”. The Secretary-General’s Plan of Action on Preventing Violent Extremism makes a clear association between PVE and development, calling for national and regional PVE action plans and encouraging member states to align their development policies with the Sustainable Development Goals, many of which were highlighted as critical to addressing global drivers of violent extremism and enhancing community resilience.

The General Secretary’s Geneva Plan of Action provides more than 70 recommendations to Member States and the UN system to support them. One of the key recommendations of the Plan is for Member States to consider adopting National Plans of Action based on national ownership.

Comments Off on UN’s indoctrinated defense against violent extremism

April 8th, 2016

By Syed Qamar Afzal Rizvi.

The Nuclear Security Summit that just ended on Friday in Washington, D.C. wrangled over several thorny nuclear proliferation and terrorism issues, and involved over 50 countries. But the two countries on everyone’s mind were China and Russia. China, because they have started on the world’s largest nuclear build-up in 50 years. And Russia, because they decided not to attend at all.

The fourth Nuclear Security Summit, in the series begun by the Obama administration, showcased definite successes, particularly the significant global reduction in nuclear weapons, the global reduction in nuclear material stockpiles, the increased security on nuclear facilities, the dozen countries that are now free of weapons-grade materials, a newly-amended nuclear protection treaty, and the historic nuclear deal with Iran that has, so far, gone as planned.

The IAEA’s role

International conventions adopted under both IAEA and other auspices have also assigned a clear role and functions to the IAEA in the field of nuclear security and have been approved as such by the Board of Governors. In particular, the Convention on the Physical Protection of Nuclear Material and the 2005 Amendment thereto, the Convention on Early Notification in the Event of a Nuclear Accident, the Convention on Assistance in the Case of a Nuclear Accident or Radiological Emergency, and the International Convention for the Suppression of Acts of Nuclear Terrorism have all assigned specific functions to the IAEA.

Non-binding legal instruments promulgated under IAEA auspices, including the Nuclear Security Recommendations on Physical Protection of Nuclear Material and Nuclear Facilities (INFCIRC/225/Revision 5) and the Code of Conduct on the Safety and Security of Radioactive Sources, also illustrate the IAEA’s role in elaborating such guidance and confirm its role in assisting States, upon request, in implementing the recommendations contained therein. Thus, like the international legal framework for nuclear security, the IAEA’s nuclear security mandate is embodied in both binding and non-binding legal instruments adopted under both IAEA and other auspices.

The notion of nuclear disarmament/ nuclear non proliferation

Over the past five years, the international community has devoted attention to the humanitarian, environmental, and developmental consequences of nuclear weapons detonations.

The final document of the 2010 Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference referred for the first time in NPT history to the “catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons” and reaffirmed the need “for all States at all times to comply with applicable international law, including international humanitarian law.”

The discourse on disarmament has also shifted in recent years to a chronic debate over what preconditions must be satisfied to make disarmament ―possible.‖ Some of these make sense and are not at all opposed by serious proponents of disarmament – there is little disagreement, for example, that nuclear disarmament commitments must be binding, irreversible, transparent, universal, and verified. Yet other preconditions – including world peace, ―solving the problem of war,‖ resolving all regional disputes, ending all proliferation and terrorist threats, and even achieving world government – clearly have the thinly-veiled purpose of simply postponing disarmament indefinitely, as other goals displace disarmament as a priority.

The dictum that ―stability and order‖ are necessary preconditions for disarmament ignores the contribution that disarmament makes in strengthening international peace and security, through confidence-building, dispelling mistrust, lessening risks of conflict escalation, eliminating the danger of nuclear war, encouraging the peaceful settlement of disputes, strengthening the legitimacy (and effectiveness) of non-proliferation efforts, and discouraging the threat or use of force – all tied in various ways to the UN Charter.

The issue of legal gap

International law clearly places very heavy restrictions on nuclear weapons use. Nevertheless, there is no unequivocal and explicit rule under international law against either use or possession of such weapons. Although the two other categories of nonconventional weapons are explicitly prohibited because their use would conflict with the requirements of international humanitarian law, the use, production, transfer, and possession of nuclear weapons are not explicitly prohibited. This may reasonably be labeled a legal gap.

The reference to this legal gap in the Humanitarian Pledge does not make it clear whether a prohibition should be separated from the process of physical elimination and, if so, which to pursue first. The question of sequencing is significant. Should prohibition precede elimination? Should elimination come first when conditions allow, with prohibition then following? Could they be pursued simultaneously, in the form of a treaty that would resemble the Chemical Weapons Convention? Should the prohibition form part of a negotiated structure of legal instruments—a formal framework that could set out an agreed sequence or foreshadow the need to agree on a sequence at the outset of the initial negotiations?

The NPT & the emerging challenges

Four main approaches to nuclear disarmament feature frequently in debates in the UN General Assembly First Committee and the NPT review cycle: (1) a comprehensive nuclear weapons convention in which a single legal instrument would provide for prohibition and elimination and in which elimination would precede a prohibition, (2) a framework agreement in which different prohibitions and other obligations would be pursued independently of each other but within the same broad frame, (3) a step-by-step or building-block approach in which elimination would precede prohibition, and (4) a stand-alone ban treaty in which prohibition would precede elimination.

Unsurprisingly, governments have different views on these approaches, depending on the country’s status under the NPT, its membership in other treaty regimes, and its military alliances. At this point, it is not clear which view will prevail. It seems safe to say, however, that the legal gap will continue to be a hotly debated topic in the months and years to come, including in the open-ended working group on “[t]aking forward multilateral nuclear disarmament negotiations” that is meeting in Geneva during 2016.

Deterrence versus horizontal application of international norms?

The doctrine of nuclear deterrence – which Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has called ―contagious – is now being implemented in various forms by nine States and many more if one includes States that are members of nuclear alliances. More people actually today live in States that have either the bomb or a nuclear umbrella than in States that are fully nuclear-weapon-free. Possessor States also maintain that it is legal to use such weapons (China and India oppose first use but have not ruled out use in response to a nuclear attack) and most oppose the negotiation of a nuclear weapons convention, with the exceptions of China, India, Pakistan, and the Democratic People‘s Republic of Korea.

The western policy of double standard

Yet if such weapons are legal to use, effective in guaranteeing national security, and recognized symbols of power and status among a majority of the world‘s population, such claims are arguably more conducive to the evolution of an unwelcome norm of possession, than to the achievement of abolition. This is why efforts to achieve nuclear disarmament will have to rely upon more than the examples being set by the nuclear-weapons states. The western policy of double standards on this issue or vertical application of nuclear norms has been the root cause of promoting resentment in the comity of nations.

The examples of this western nuclear policy of nuclear segregation/favouritism can be rightly understood keeping in view the cases of both India & Israel.

A humanitarian approach based on non-use therefore would probably best be pursued not in isolation but as a clause in a nuclear weapons convention, as non-use was handled by the Chemical Weapons Convention and, indirectly, by the Biological Weapons Convention.

The successful efforts to negotiate treaties (though still not universal in membership) on anti-personnel landmines and cluster munitions did not seek merely to limit the use of such weapons – non-use was explicitly incorporated as a part of a disarmament (or nonarmament) commitment, and this seems a sensible approach for nuclear weapons as well.

Based on humanitarian law principles, and the evolving rule of law in disarmament, the only legitimate ―sole purpose of nuclear weapons (and other WMD) or, one day, even South Asia). All of these would complement the common purposes shared by the existing regional nuclear-weapon-free zones in Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, the South Pacific, Southeast Asia, and Central Asia.

Comments Off on International law: Nuclear security & use of nuclear weapons

April 4th, 2016

By Syed Qamar Afzal Rizvi.

Unnerved by the fact that one of its leading “Monkeys”, in service senior Raw officer Kulbashan Yadav, has got into the hands of Pakistan, New Delhi is frustratingly trying to get consular access which it had never demanded before in any other case. ‘Capture of spy proves Indian interference in Pakistan: Army’ said Dawn, Pakistan’s most sober newspaper – its headline departing from the rest by attributing the information about Jadhav (and the assessment of his ‘confession’) to the army. The newspaper quoted the military spokesman as saying Jadhav’s confession “is solid proof of Indian state-sponsored terrorism”. The article reveals that the captured India will be ‘prosecuted as per the law of the land’ and decisions regarding consular access for Indian authorities will be taken at a later date.

While Pakistani security agencies are preparing a strong case to expose India’s state-sponsored terrorism against Pakistan and there are hints of something more to unfold in the days to come, Indian propaganda machinery is frustratingly asking for consular access of Kulbashan Yadav aka Mubarak Hussain Patel. In response to Indian demand, Pakistani security agencies sources offer, “ India will have to accept, first, all the crimes of Kulbashan only then Pakistan will consider to exercise its discretion in granting the consular access or otherwise.”

Espionage & international law

The core of espionage is treachery and deceit. The core of international law is decency and common humanity. This alone suggests espionage and international law cannot be reconciled in a complete synthesis.

Espionage is curiously ill-defined under international law, even though all developed nations, as well as many lesser-developed ones, conduct spying and eavesdropping operations against their neighbors.’ Examined in light of the realist approach to international relations, states spy on one another according to their relative power positions in order to achieve self-interested goals. This theoretical approach, however, not only fails to explain international tolerance for espionage, but also inadequately captures the cooperative benefits that accrue to all international states as a result of espionage. Although no international agreement affirmatively endorses espionage, states do not reject it as a violation of international law.’

As a result of its historical acceptance, espionage’s legal validity may be grounded in the recognition that “custom” serves as an authoritative source of international law. Espionage is a crime under the legal code of many nations.

In the United States it is covered by the Espionage Act of 1917. The risks of espionage vary. A spy breaking the host country’s laws may be deported, imprisoned, or even executed.

The Third Amendment Amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan is an amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan went effective on 18 February 1975, under the Government of elected Prime ministrer Zulfikar Ali Bhutto an amendment to the 1973 Constitution of Pakistan. The amendment extend the period of preventive detention, of those who are accused of committing serious cases of treason and espionage against the state of Pakistan, are also under trial by the government of Pakistan.

A spy breaking his/her own country’s laws can be imprisoned for espionage or/and treason (which in the USA and some other jurisdictions can only occur if he or she take ups arms or aids the enemy against his or her own country during wartime), or even executed, as the Rosenbergs were. For example, when Aldrich Ames handed a stack of dossiers of U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) agents in the Eastern Bloc to his KGB-officer “handler”, the KGB “rolled up” several networks, and at least ten people were secretly shot. When Ames was arrested by the U.S.

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), he faced life in prison; his contact, who had diplomatic immunity, was declared persona non grata and taken to the airport. Ames’s wife was threatened with life imprisonment if her husband did not cooperate; he did, and she was given a five-year sentence. Hugh Francis Redmond, a CIA officer in China, spent nineteen years in a Chinese prison for espionage—and died there—as he was operating without diplomatic cover and immunity.

International humanitarian law and its application

According to Article 29 of customary International Humanitarian Law, “A person can only be considered a spy when, acting clandestinely or on false pretences, he obtains or endeavours to obtain information in the zone of operations of a belligerent with the intention of communicating it to the hostile party.” If Pakistan can sufficiently establish through proof that the Yadav is a spy then his rights for consular access are automatically forfeited. No country has the right to treat unlawful combatants or spies inhumanely.

Article 30 of the same law states, “A spy taken in the act shall not be punished without previous trial.” India and Pakistan have been trying spies in military courts. The sentences have been rarely challenged in the Supreme Court. More recently, India has been exerting civil society pressure on the pretext of humanitarian grounds. In one case, an attempt was made to shield a convicted spy as a case of mistaken identity.

Sovereignty & international law

Sovereignty is a core precept of public international law, guarding a state’s essentially exclusive jurisdiction over its own territory. A concomitant principle is that “[e]very State has the duty to refrain from intervention in the internal or external affairs of any other State” and “the duty to refrain from fomenting civil strife in the territory of another State, and to prevent the organization within its territory of activities calculated to foment such civil strife.”

The principle of non-interference in sovereign affairs is recognized most famously in the U.N. Charter itself, which provides in Article 2(4) that “[a]ll Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.” The principle is, however, broader than this preoccupation with use of force suggests.

As the influential General Assembly Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Co-operation Among States in Accordance with the Charter of the United Nations declares, “[e]very State has an inalienable right to choose its political, economic, social and cultural systems, without interference in any form by another State” and “[n]o State or group of States has the right to intervene, directly or indirectly, for any reason whatever, in the internal or external affairs of any other State.” While not itself a source of public international law, the Declaration is almost certainly a reflection of current customary international law.

The Indian case

There are undoubted examples of espionage – broadly defined to include, e.g., covert military assistance – that exceed the non-interference standard. In the case of Yadav, Islamabad is unlikely to budge given the ‘evidence’ of Indian support for terrorism in Balochistan and Karachi, which adds up in the statement of Premier Modi in Bangladesh of severing East Pakistan and then by those of his defense minister Manohar Parrikar and Ajit Doval, advisor on national security.

The exercise of what is known as “enforcement jurisdiction” by one state and its agents in the territory of another is clearly a breach of international law – it is impermissible for one state to exercise its power on the territory of another, absent consent or some other permissive rule of international law. Keeping this yardstick in mind, It appears that Indian spying over Pakistani territory is in gross violation of international law.

Pakistan is collecting evidence to prove India is a direct sponsor of terrorism. The fact of the matter is that if the confession- made by Yadav- indulges his activities in promoting Indian sponsored state terrorism against Pakistan,there is much likelihood that the case may take a grave turn.

The UN’s role may be a significant step in this case. Pakistan has already submitted to the UN officials the dossier regarding Indian terrorist involvement in Pakistan. Now,with the rising of Yadav’s case, Islamabad may hold the expectations that the UNSC should refer the case to the International Criminal Court(ICC).

“We have briefed the P5 (the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council) and the European Union on the issue,” Zakaria,Pakistan’s Foreign Office Spokesperson said. He added that Yadav’s revelations had vindicated Islamabad’s position and exposed India’s designs against Pakistan.

Comments Off on Indian espionage in Pakistan versus international law

March 28th, 2016

By Qamar Syed.

Pakistan is Afghanistan‟s most important neighbour, since it shares with Afghanistan history, ethnicity, religion and geography in ways none of its other neighbour does. We can, therefore, reasonably expect Pakistan to be more proactively concerned with the Afghan situation at this critical stage and reshape its own Afghan outlook accordingly. And it seems reasonably logical to conclude that the search for a lasting peace solution in Afghanistan has been lost because of the ongoing conflict of interests among regional actors.

Pakistan’s Afghan policy

Generally, discussions on Pakistan focus on its role in the ‘War on Terror,‟ whereby its support to Afghan Taliban is presumed as a given reality. In the process, any possibility of change in state approach to regional conflicts such as Afghanistan according to new circumstantial realities is often overlooked.

Pakistan did pursue a policy of „strategic depth‟ in the 1990s and faced international criticism for supporting Taliban during the current Afghan war. While such aspects of Pakistan‟s past Afghan policy deserve critical review, a question more relevant to the current context, and therefore worth examining, is how it is responding to the certainty of Western military exit from Afghanistan and corresponding uncertainties associated with the state of war and the prospect of peace in Afghanistan.

The evidence in the last few years, in the form of policy pronouncements by Pakistan‟s civil-military leadership and meaningful governmental initiatives, suggests the country has, indeed, taken a visible shift in its Afghan policy. What are its underlying motivations? Is this shift part of a broader transformation currently under way in Pakistan‟s regional priorities? And how far can it help in achieving sustainable Afghan peace and viable regional stability? Realism constitutes a more appropriate framework to answer these questions, since pragmatic considerations seem to underpin the evolving transformation in Pakistan‟s Afghan policy and regional outlook. However, its manifestations and motivations cannot be understood without a brief reference to Pakistan‟s past relationship with Afghanistan.

Despite those efforts by the new administration, there were credible suspicions that the Taliban continued to receive support from their foreign benefactors to wage war against the people and government of Afghanistan. Moreover, the misgiving between the two neighbors culminated in the brief fall in October of Kunduz , a strategic province in northern Afghanistan that connects the country to Central Asia.

On the other hand, the rising insecurity in different provinces initiated from the Taliban sanctuaries in Pakistan further damaged ties between Afghanistan and Pakistan. The acrimony and mistrust peaked to the point that President Ashraf Ghani in August publicly announced the withdrawal of political support to Pakistan for the reconciliation process and said that he would work with other stakeholders in the region in order to bring peace and stability to his country.

Firstly, it appears that Pakistan is losing its enduring influence over the fracturing Taliban movement. From Pakistan’s perspective, the Taliban, which has split into two major groups, are unable to turn the tide militarily. For this reason, there has to be a political solution to the Afghan crisis so that it can focus on its own domestic security problems.

To this end, a settlement could be achieved with the faction of Mullah Mansour, successor to Omar, who has close ties with Pakistani establishment. Secondly, given the split among Taliban ranks, any resolution that could maintain a modicum of Pakistani influence over the group is in the best interest of the country towards normalization of relations and reaching a favorable political solution with Kabul. Finally, with perpetual instability in Afghanistan, the security situation in Pakistan will also remain fragile because of the intertwined connection among various militant groups active in both countries.

Sure enough, with the announcement of Mullah Omar’s death, momentum toward peace came to a halt. The meeting set for July 31(2015) was postponed indefinitely. Then Omar’s successor, Mullah Akhtar Mohammed Mansour, rejected negotiations altogether and reissued the call for jihad against the United States and the Afghan government. Nearly a week after that, over the course of four days, three bombings wrecked Kabul, killing and injuring nearly 400 Afghans. The Taliban claimed responsibility. The question now is whether the window for peace talks is closed.

Talking to Taliban

The Taliban are immersed in a power struggle. Mansour is trying to secure his position against defiant rivals such as Abdul Qayum Zakir and Omar’s son Yakub, who question his right to rule. There are two possible outcomes to these struggles, each with its own implications for negotiations. One outcome is that the Taliban movement stays united. A single leader—Mansour

Afghanistan’s peaceful future depends to a great extent on an auspicious regional environment, with Pakistan at its core. Vice versa, an unstable Afghanistan will complicate Pakistan’s ability to refurbish its weak state and economy and suppress dangerous internal militancy. Assassinations and military coups have plagued Pakistan since the early years of independence, leaving behind a weak political system unable to effectively deliver elementary public goods, including safety, and respond to the fundamental needs of the struggling Pakistani people.

Rather than being a convenient tool for regional security schemes as Pakistani generals have often imagined, an Afghanistan plagued by intense militancy, with Kabul unable to control its territory and effectively exercise power, will distract Pakistan’s leaders from addressing internal challenges. Such a violently contested, unsettled Afghanistan will only further augment and complicate Pakistan’s own deep-seated and growing security and governance problems.

Pakistan fears both a strong Afghan government closely aligned with India, potentially helping encircle Pakistan, and an unstable Afghanistan that becomes—as has already happened—a safe haven for anti-Pakistan militant groups and a dangerous playground for outside powers. Whether the recent warming of relations between the two countries, following a change in government in Kabul in September 2014 when Ashraf Ghani became president, translates into lasting and substantial changes in Pakistan’s policy remains very much yet to be seen.

The Indian role

Now a word about India’s role in Afghanistan. It has invested more than 2 billion dollars in that country. It patronizes a number of top leaders of Northern Areas including Dr Abdullah Abdullah and Dostum and has made big strides in cementing relations between the two countries. As for back as 2011 we witnessed Mr. Karzai entering into a strategic partnership agreement with India which included training of senior military Afghan officers in India. India is also deeply involved in exploiting Pakistan’s problems in various parts of the country.

For evidence please read the following excerpts from speeches by what ex-US Defence Secretary Chuck Hegel and General Stanley McChrystal had said in their talks on Afghanistan: that India had been using Afghanistan as a second front against Pakistan and over the years financed problems for Pakistan. General Stanley McChrystal, former Commander of ISAF, had said, “Increasing Indian influence in Afghanistan is likely to exacerbate regional tensions and encourage Pakistani countermeasures. The recent worsening of relations between India and Pakistan is bound to encourage New Delhi to step up its unwholesome anti Pakistan activities. How weighty is the Pakistan evidence about details of India’s subversive activities in Balochistan and FATA, is yet to be known.

The tug of interests

While closely intertwined, the intra-Afghan and regional dimensions are often addressed separately or in the wrong order, starting with the regional angle and reducing the intra-Afghan settlement to a function of the interests of regional powers. With such an approach, one easily falls into the trap of conflicting national interests (between, for example, Pakistan and India, Iran and Pakistan, and the Gulf States and Iran). Such controversies do not prevent multilateral dialogue on Afghanistan, but they easily surpass the impact of any regional framework.

Ultimately, even a degree of balance among the interests of regional powers does not substitute for a genuine political settlement in Afghanistan. The right order, hence, is the reverse: a solution must begin with an adequate intra-Afghan settlement, formulated in a way that accommodates the main legitimate concerns of key regional stakeholders (first and foremost, Pakistan and Iran).The approach via Brahimi-Pickering plan seems pragmatic.

The intra-Afghan regionalization arrangement outlined in the previous section stands a chance of striking a balance between the domestic dimensions of settlement and the interests of key regional stakeholders. While the proposed decentralized framework for Afghanistan will not primarily be driven by—or satisfy—the maximum demands of regional powers, it will be in line with their legitimate interests. The Pakistan-supported Pashtuns in Taliban-controlled areas will receive a significant share of formal power at the regional level while remaining a constituent part of the decentralized Afghan state.

Regions with Shia dominance or a mixed population with a significant Shia presence will enjoy the same degree of autonomy. In particular, Hazarajat, as the most vulnerable region with the most victimized population, will likely become a natural center of gravity for any modified international presence. Iran will continue to play its role as the traditional benefactor of Afghanistan’s Shia and Persian-speaking populations and, together with other states like Uzbekistan, Russia, and India, support the northern regions.

The new hopes

The third meeting of the Quadrilateral Coordination Group (QCG) on Afghanistan at Islamabad on Saturday ended on a positive note. The QCG (comprising Afghanistan, Pakistan, US and China) adopted a road map, which was under discussion in the two earlier meetings last month, “stipulating the stages and steps” of the reconciliation process, as the Joint Press Release put it. The road map pertains to the parameters of shared responsibilities of the involved parties in the QCG mechanism. Its formal adoption was no big surprise but is a necessary step forward nonetheless.

Second, the QCG will keep up the momentum by holding its next meeting shortly on February 23 at Kabul. Third, importantly, the QCG expects that direct talks between the Afghan government and Taliban will take place “by the end of February”.

The QCG meeting “stressed that the outcome of the reconciliation process should be a political settlement that results in the cessation of violence, and durable peace in Afghanistan”.

The QCG had earlier reached a consensus that there shall be no ‘pre-conditions’ attached to the peace talks. There is now the added recognition that some ‘confidence-building measures’ are useful to cajole the Taliban to walk toward the negotiating table.

So, how does the balance sheet look? The jettisoning of pre-conditions means that Taliban cannot insist they first want to discuss the withdrawal of foreign troops. On the other hand, Kabul government cannot insist on Taliban bidding farewell to arms before talks begin.

Meanwhile, Pakistan has accepted that reduction in violence should be an important objective of the consultations. But Pakistan has underscored that the objective should be to bring in as many Taliban groups as possible into the peace talks. Presumably, it cannot be a ‘pre-condition’ on anyone’s part that, say, the Haqqani Network cannot participate.

Comments Off on Afghanistan: Peace dwindled in tug of ‘conflicting interests’

March 22nd, 2016

by Syed Qamar Rizvi.

Turkish and EU leaders on Friday agreed a “historic” deal for curbing the influx of migrants that has plunged Europe into its biggest refugee crisis since the end of World War II.

Turkey extracted a string of political and financial concessions in exchange for becoming a bulwark against the flow of desperate humanity heading to Europe from Syria and elsewhere.

“It is a historic day because we reached a very important agreement between Turkey and the EU,” Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu said after the deal was struck at a summit in Brussels.

The dividends for EU & Turkey

After two days of negotiations, Turkey and the European Union reached a compromise agreement on a plan to reduce the flow of migrants from the Middle East to Europe. At a summit concluding March 18, the heads of government of the 28 EU members and their Turkish counterparts approved the plan, which should take effect March 20. While the deal could help reduce the number of migrants arriving in Europe, questions remain about the signatories’ ability and commitment to fully enforce it. The EU is also set to increase the €3 billion ($3.3 billion) it had already committed to help Turkey cope with millions of refugees.

In return, Turkey plans to take back migrants who arrive in Greece from Turkish shores, including Syrian refugees. For the latter, the deal would operate under a one-for-one principle, whereby EU countries would take Syrian refugees from camps in Turkey for every Syrian refugee Turkey takes back from Greece. The idea is to ensure there is only a legal, organized channel for Syrian migration to the bloc.

Previously, Turkish authorities were committed only to taking back asylum seekers whose claim was rejected by the EU after June 1 this year.

Turkey came into Monday’s EU summit demanding a doubling of EU assistance to €6 billion ($6.6 billion) and faster timetables for EU membership and visa-free access to the bloc than were in a previous migration deal reached in November.

With the March 18 agreement, Ankara agreed that all migrants arriving in Greece from Turkey will be sent back to Turkey. And for every Syrian migrant sent back to Turkey, a Syrian in Turkey will be given asylum in the European Union. The plan, however, caps the number of Syrians who can be sent to Europe from Turkey at 72,000. If that limit is reached, the European Union and Turkey would have to renegotiate.

The issue of Turkey’s EU bid

The agreement makes partial concessions to Turkey. In exchange for accepting returned migrants, Turkey wanted to open five chapters of its accession negotiation with the European Union. (In EU accession talks, chapters represent aspects of an applicant country’s policy that must be evaluated in comparison with EU standards before it can join the bloc.) The Cypriot government countered with demands for a stronger Turkish commitment to reunifying Cyprus, which was divided into distinct Greek and Turkish states after Turkey invaded in 1974. As a result of the talks, EU leaders compromised, agreeing to open only one mostly technical and not particularly controversial chapter.

The growing hopes

If implemented properly, the new plan could discourage migrants from trying to reach Greece. The idea is to punish people who try to reach Greece illegally by sending them back to Turkey, relegating them to the bottom of the list of asylum applicants. At the same time, people who wait in Turkey and use official channels to pursue asylum will be rewarded for their patience. But for the deal to work, Turkey will have to better prevent migrants from reaching Greece, and Greece will have to become more efficient at processing asylum applications.

So far, efforts to regulate the flow of migrants have been disappointing. On March 17, German media reported that German officials working on the recently approved NATO patrolling operation in the Aegean Sea are frustrated by its limited effect; human trafficking organizations are still managing to avoid controls and reach the Greek islands.

What the European reformists think

European Conservatives and Reformists group home affairs spokesman Timothy Kirkhope MEP has written to all 28 EU leaders and the Presidents of the European Council and Commission urging a rethink of the agreement.

He said:

“This agreement must not be rushed into in desperation. EU leaders need to think long and hard about the widespread implications it will have. European Prime Ministers must not become so anxious to be seen to do something that they end up doing the completely wrong thing.

“We seem to be breaking a number of our own rules and conventions, we are risking continued unsustainable levels of economic migration into the EU, we risk shifting pressures to other routes, and we are giving away six billion euros with no way of ensuring it will be used effectively. This is not a workable agreement.

“Turkey must be a major partner in stemming the flow of economic migrants, but it cannot do our job for us. An ambitious UNHCR-led resettlement scheme can be delivered alongside a strong readmission agreement with Turkey, then the resources we are handing away could be spent in Europe on detention, processing and returns. We need to get the basics right and stop trying to find a solitary solution that does not exist.”

The concept of emergency brake

An emergency brake built in to any deal with Turkey and activated if certain conditions are breached, or identified following an assessment by the European Commission. Such breaches would include:

1: An unmanageable number of persons having to be resettled within the EU. 2: Human rights violations by Turkey of those being returned. 3: Any misuse of the funds given by the EU.

It is my strong belief that EU leaders would be far better creating an ambitious UNHCR led resettlement scheme from Turkey and from conflict regions. This can be delivered by strengthening and expanding the existing EU Turkey readmission agreement, and using the funds being offered to Turkey to stabilise the EU’s external border, increase the capacity of EU agencies operating in hotpots and the external border, to speed up the process of asylum procedures, combat human trafficking, and provide dignified and adequate living conditions for those already in the EU.

To ensure the support of the European Parliament, the European Council must show that it respects the laws and international conventions in place, as new legislation is likely to require agreement of the co-legislators. We must not fight illegal immigration through illegal means ourselves.

Challenges ahead

As NATO and Turkey tightened patrols, and hundreds trying to make the journey were intercepted on Saturday, the fate of thousands already stranded in Greece remains unclear.

Conditions are increasingly desperate at the vast Idomeni tent camp on the closed Macedonian border. Aid agencies believe the situation is set to go from bad to worse.

“From the International Rescue Committee’s perspective, the deal is only going to lead to more disorder, more lack of dignity,” said IRC spokesperson Lucy Carrigan in Idomeni.

“The idea that you can base resettlement on conditions that people are returned from Greece to Turkey is unethical.”

Ironically, Turkey’s liberals, who have been the strongest supporters of Turkish EU membership for decades, are not thrilled with the new rapprochement between Ankara and Brussels. The lingering question on their minds is whether the deal will come at the cost of what little Turkish democracy remains. Turkey’s EU candidacy has long served as an engine of constitutional reform and democratic transition. To fulfil the Copenhagen criteria, Turkey undertook constitutional amendments to reform the judiciary, curb the military’s power in politics and strengthen fundamental rights and freedoms.

The deal & international law

The refugee crisis has left Europe increasingly divided, with fears that its Schengen passport-free zone could collapse as states reintroduce border controls and concerns over the rise of populist parties on anti-immigration sentiment.

European leaders voiced caution about whether they can finally seal the deal with Turkey, which has been trying to join the EU for decades.

Tusk said earlier he was “cautiously optimistic but frankly, more cautious than optimistic” while German Chancellor Angela Merkel warned there were “many things to resolve”.

Other EU leaders voiced worries that the deal – under which the EU would take in one Syrian refugee from Turkish soil in exchange for every Syrian taken back by Turkey from Greece – would be illegal.

The aim of the “one-for-one” deal is allegedly to encourage Syrians to apply for asylum in the EU while they are still on Turkish soil, instead of taking dangerous smugglers’ boats across the Aegean Sea.

Lithuanian President Dalia Grybauskaite said the plan was “very complicated, will be very difficult to implement and is on the edge of international law”.

Despite the fact that all 28 EU member states have agreed to the terms of the final deal set out by Tusk, the experts on international law see this agreement with warranted suspicion. And there is also a growing concern in the European civil society that this agreement may cause a great harm to EU’s image as a soft power. But to predetermine any viable scope regarding this utilitarian agreement between Brussels and Ankara, yet remains a prophetic task.

Comments Off on EU-Turkey accord on Syrian refugee crisis?

March 20th, 2016

By Syed Qamar Rizvi.

Geopolitics via CPEC

The China-Pakistan economic corridor is a significant bilateral agreement which has the potential to reconfigure the geopolitics of the South Asian region. China is set to invest $46 billion in this economic corridor which runs from Gwadar, a deep sea port in the province of Baluchistan in Pakistan to Kashgar in China’s northwest province of Xinjiang with roads, railways and pipelines. The Gwadar port lies on the conduit of the three most commercially important regions namely – West Asia, Central Asia and South Asia.

China-Pakistan growing strategic partnership

Meanwhile, China’s interest in deepening involvement with Pakistan is neither new nor particularly difficult to understand. With the United States having ended official military operations in Afghanistan in 2015, its interest in the region has declined somewhat, and China has effectively stepped into the vacuum created by America’s diminishing interest in Pakistan and the Asian subcontinent.

Thus, the East Asian nation has increased its long-term economic and strategic interest in Pakistan with the aim of strengthening its position in the world. In accordance with this overall strategy, China’s political leaders have been prepared to invest in Pakistani infrastructure, a decision which has obviously met with approval in the country that has struggled with economic and terrorism-related issues in recent years. The question which would obviously arise for policymakers in Washington is how this project will affect American interests in the region.

Geostrategic significance

It is expected to become a terminus point for trade and energy corridor emanating from the Central Asian Region. Operational control of this port gives the Chinese strategic and geopolitical advantage for the following reasons: First, the port is strategically located not far from the Strait of Hormuz and at the mouth of the Persian Gulf. Second, the Chinese face

considerable economic and strategic challenges from the US presence in the Asia-Pacific and the Gwadar port will provide a listening post to keep a tab on the US naval activities 460 kilometres further west from Karachi and away from the Indian naval bases. Third, the Chinese have expedited the process of developing Gwadar around the same time as US announced withdrawal of forces from Afghanistan, thus allowing them to conduct economic ventures in Afghanistan and other Central Asian countries. The Chinese aim to use Pakistan as a pipeline corridor to procure oil and gas from West Asian countries, especially Iran.

The growing Chinese benefits

Much is being said about the $46bn worth of Chinese investment coming into Pakistan. Although all analyses are speculative in tone, there is the understanding that this presents Pakistan with an opportunity to end its chronic power crisis and put its economy back on track. China, with its ever-increasing wistfulness to link up with Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe, is planning to go ahead with its long-planned economic corridor known as the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

This cohesive plan to develop Pakistan into an economic and energy hub entails coal, hydro, solar and wind plants. The corridor is a link between the prospective Northern and Southern Silk Roads that China is heavily focusing on in order to establish a transit for its manufactured goods all the way to Europe, the Middle East and Africa respectively.

This will allow China to monitor the vulnerable sea lines of communication as 60 per cent of its crude supply comes from West Asia. Moreover, most of its supply will be moved through this port which will save China millions of dollars, time and effort. This in a way will help reduce its dependence on the Strait of Malacca. China has also shown interest in joining the US$7.4 billion Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline, a project that faces stiff opposition from the US.

Russia and the CPEC

Perverted in the Western imagination as a backwards land of terrorism and poverty, the mainstream media myth about Pakistan carries little factual weight and purposely neglects the country’s rising geopolitical importance in Eurasia. Far from being a lost cause, the country is actually one of the supercontinent’s most important economic hopes, as it has the potential to connect the massive economies of the Eurasian Union, Iran, SAARC, and China, thereby inaugurating the closest thing to an integrated pan-Eurasian economic zone.

Russia recognizes Pakistan’s prime geopolitical potential and has thus maneuvered to rapidly increase its full-spectrum relations with the South Asian gatekeeper. Russia’s overarching goal, as it is with all of its partners nowadays, is to provide a non-provocative balancing component to buffet Pakistan’s regional political position and assist with its peaceful integration into the multipolar Eurasian framework being constructed by the Russian-Chinese Strategic Partnership.

The Indian factor

South Asia’s geopolitics were transformed by the end of the Cold War and the subsequent nuclear bipolarity that arose between India and Pakistan. The conclusion of the global ideological stand-off lessened the intensity of the Russian-Indian Strategic Partnership and the US’ dealings with Pakistan, as South Asia was no longer seen as a priority area of foreign policy focus by either superpower after that time. As a result, India began to drift westward at the same time that Pakistan was moving eastward, with New Delhi looking towards Washington while Islamabad embraced Beijing. This doesn’t mean that either of them completely turned their backs on their historical partners (Russia and the US, respectively), but that the changing global context forced them to adapt to a new reality of relations that continued the furtherance of their national self-interests.

The Afghanistan factor

The Afghanistan factor

The completion of this CPEC project would also enable China to link up with its significant economic and oil interests in neighboring Afghanistan. It is thus of interest that the former Afghanistan president, Hamid Karzai, has recently explicitly warned China and Russia of dangers emanating from ISIS involvement in Afghanistan. It could be that China is moving to cement its interest in the region at the moment with the CPEC project, while one can also see Afghanistan being a significant theater of conflict in the future between the Anglo-American old word order and the new BRIC-based superpowers.

Thus, the CPEC project may not be particularly common knowledge in the Western world at the moment, but it will almost inevitably play a role in a wide variety of geopolitical issues that will play out on the world stage in the coming years.

The Environmental challenges

China’s aid is more focused on developing Pakistan’s energy and infrastructure sectors as can be seen from the multi-faceted approach adopted by the latter in its program. What remains to be seen is whether the possible environmental implications of heavy reliance on coal-based energy have been thoroughly evaluated and clearly communicated to the Chinese. Does Pakistan even have a disciplined, well-funded and efficient disaster management infrastructure in place to monitor the repercussions of this grand endeavor? Have the relevant stakeholders been a part of the negotiation and planning process to ensure that Pakistan safeguard itself against the associated risks? Being a third world country, Pakistan is perhaps more prone to the hazardous impact of climate change. Hence, it is important to integrate the environmental perspective whilst embarking on the ambitious plan.

The Baluchistan factor

The security landscape in Balochistan needs to be monitored in this regard since it is rife with militant and sectarian violence. Maintaining stability and order in the province is of paramount importance for the successful implementation of the CPEC. It is crucial thus, to work towards facilitating

the evolution of a more inclusive approach at the state level as far as enabling Baloch participation in the plan is concerned.

Iranian factor

As far as Iran is concerned, Chinese promises of extending the Iran-Pakistan pipeline all the way to the Xinjiang capital of Kashgar offers incentives to Iran to remain optimistic about this initiative: the gradual lifting of American sanctions from the country has infused hope and positivity.

The dynamic nature of the US-Iran relationship in contemporary times has also reinforced the idea that we are looking towards a future of new precedents vis-à-vis forming alliances and forging cooperation in the wake of converging interests and the desire for greater economic connectivity. The course of foreign relations today in terms of leanings and longevity may be much harder to predict as we make the transition towards a multipolar world.

It will be absolutely fascinating to watch how China and Pakistan, simultaneously, may be able to keep the peace in both Xinjiang and Balochistan to assure booming trade along the corridor. Geographically though, this all makes perfect sense.

Xinjiang is closer to the Arabian Sea than Shanghai. Shanghai is twice more distant from Urumqi than Karachi. So no wonder Beijing thinks of Pakistan as a sort of Hong Kong West.

This is also a microcosm of East and South Asia integration, and even Greater Asia integration, if we include China, Iran, Afghanistan, and even Myanmar.

The spectacular Karakoram highway, from Kashgar to Islamabad, a feat of engineering completed by the Chinese working alongside the Pakistan Army Corps of engineers, will be upgraded, and extended all the way to Gwadar. A railway will also be built. And in the near future, yet another key pipeline is in the offing.

This pipeline is linked to the corridor also in the form of the Iran-Pakistan (IP) gas pipeline, which Beijing will help Islamabad to finish to the tune of $2 billion, after successive U.S. administrations relentlessly tried to derail it

The geopolitical dividends of China blessing a steel umbilical cord between Iran and Pakistan are of course priceless.

A new heraldry of Pak-China epic relationship

Traditionally, China and Pakistan have had a relatively profitable relationship. For over half a century, diplomatic relations between the two countries were pretty warm and friendly. However, the recent unveiling of the 2,900 km China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) during a visit to Pakistan by Chinese President Xi Jinping has had a significantly positive influence over the relationship.

Despite being encapsulated in never-ending security conundrums, Pakistan finally has a shot at emerging from murky waters. This has also propelled a number of other related questions. How the country’s security disputes with its neighbors figure into the equation is an important one.

The project in question is worth $46 billion, and involved as part of its remit is the construction of roads, railroads and power plants. This is an extremely broad-based infrastructure project, which will take 15 years to complete. Although this was a particularly significant landmark in Pakistan-China relations, it can also be seen in the wider context of numerous other agreements in the fields of military, energy and infrastructure in particular.

CPEC is one of numerous bilateral agreements being initiated in the world at the moment which is of geostrategic importance. CPEC is also buttressed by some earlier agreements between the two nations, ensuring that its qualitative importance is increased.

In April 2015, China was granted operation rights to the port of Gwadar on the Indian Ocean, in a strategically important location of the heart of the Persian Gulf. In exchange for this privilege, Beijing is later expected by analysts to invest over $1.5 billion in the region.

The development of this economic corridor is a win-win situation for both Beijing and Islamabad. This holds tremendous potential as it would increase economic prospects and activity in Pakistan. The pre-existing ports, Karachi and Qasim, cannot handle much more traffic and Gwadar will help accommodate the increasing domestic demand. It will also enable