October 31st, 2017

By Marcus J. Ranum.

In various postings this year, I’ve been guarded about the Russian attribution of the DNC email hacks.

As I said in [stderr]:

To accurately establish attribution, you need evidence and understanding:

- Evidence linking the presumed attacker to the attack

- An understanding of the attacker’s actions, supporting that evidence

- Evidence collected from other systems that matches the understanding of the attacker’s actions

- An understanding of the sequence of events during the attack, matching the evidence

Until this point, I deliberately maintained a position of strict skepticism regarding Russian involvement (while admitting it was likely or even highly likely) It’s still possible that someone crafted the reported evidence, but unless we want to live our lives as radical skeptics eventually we can accept something as a given as long as contradictory facts don’t emerge. A lot of people were comfortable accepting the arguments that the US Government (notably the FBI and the ‘5 intelligence community agencies’) collectively asserted – I was not, because my assessment of their assertions was that they didn’t provide evidence that they doubtless had, consequently, I felt I had to wonder “why not?” and whether that evidence was any good.

I’ll note that the US Government still hasn’t provided anywhere near the kind of quality attribution that I’d expect they could if they tried. I freely admit that I hold that against them: they collect this stuff and it’s their job – as I see it – to distribute information that will help us better understand attacks that are being made against US government and corporate networks. Obviously we disagree about what their job is.

In terms of my components of a good attribution, we now have:

Evidence linking the presumed attacker to the attack: George Papadopolous was being played by someone he believed was directly connected to Putin, and was being offered dirt on Clinton “on or about” April 26. The DNC emails were leaking between January and May, so if Papadopolous’ contacts with the emails had them, they were getting them in real-time or near real-time. That establishes a linkage between the attacker and the attack that I am willing to accept.

An understanding of the attacker’s actions, supporting that evidence: Papadopolous’ contacts were claiming that they were tied in with Russian interests and had access to the emails and wanted to arrange a meeting with the Trump campaign. That is completely consistent with the overall story that has been promulgated, so far, that the Russians were trying to lure the Trump campaign into compromising itself with some dirt. Papadopolous has now admitted that that was exactly what he was doing, and what he believed the Russians were doing. I accept the story, now.

Evidence collected from other systems that matches the understanding of the attackers’ actions: This element of the attribution is still thinner than I’d like but the timing on the documents that Wikileaks eventually released matches the story of how the documents were compromised, shopped around between Papadopolous/the Trump Campaign and Wikileaks. I don’t think we need to see the various emails going back and forth; all the information Papadopolous has provided is congruent with Wikileaks’ version and the accounts of the DNC break-in from Crowdstrike. I think Crowdstrike could have provided better information but almost certainly were told not to by the FBI who were keeping that information in order to strengthen their own attribution if congruent pieces of the puzzle later emerged. In fairness to the FBI I will note that having whatever information Crowdstrike provided to them kept secret probably made it harder for Papadopolous to lie about any of the timing of these events and subsequent emails. So, while I complain about the FBI’s actions, I understand them.

Evidence collected from other systems that matches the understanding of the attackers’ actions: This element of the attribution is still thinner than I’d like but the timing on the documents that Wikileaks eventually released matches the story of how the documents were compromised, shopped around between Papadopolous/the Trump Campaign and Wikileaks. I don’t think we need to see the various emails going back and forth; all the information Papadopolous has provided is congruent with Wikileaks’ version and the accounts of the DNC break-in from Crowdstrike. I think Crowdstrike could have provided better information but almost certainly were told not to by the FBI who were keeping that information in order to strengthen their own attribution if congruent pieces of the puzzle later emerged. In fairness to the FBI I will note that having whatever information Crowdstrike provided to them kept secret probably made it harder for Papadopolous to lie about any of the timing of these events and subsequent emails. So, while I complain about the FBI’s actions, I understand them.

An understanding of the sequence of events of the attack, matching the evidence: This is the piece of the puzzle that flips me from “skeptical” to “convinced.” Papadopolous’ exchanges with the Russians happened in the right sequence of time within the broader sequence of events and there is no contradiction. If Papadopolous was talking to the Russians “on or about” April 26 about getting a drop of dirt on Clinton, that fits with the story that the data went:

Hacker -> Russians -> (offered to Papadopolous) -> (given to Wikileaks) -> Published by Wikileaks

not

Hacker -> Wikileaks -> (shared with Russians somehow) -> (offered to Papadopolous) -> Published by Wikileaks

The latter wouldn’t be consistent with how Wikileaks operates and has operated, or how Papadopolous, or his Russians operated.

There are still plenty of loose ends but I think they are mostly curiosity. Was the hacker part of the Russian government, or merely “affiliated” to some degree? That’s an irrelevant question because “affiliation” doesn’t mean much; the programmers who are writing malware for NSA’s “Equation Group” are probably contractors, not employees – are they “US Government hackers”, “US Government affiliated hackers”, or “Patriotic American hackers who choose to share things with the US Government sometimes (like, when they are paid)”? I have no idea what the org chart of the Russian cyberintelligence efforts look like, and I suspect nobody does – any more than anyone knows what the org chart of the NSA looks like if you were to include contracting companies that make more than 80% of their revenue from NSA and CIA on it. I am comfortable with accepting that there’s a tight linkage between Papadopolous’ Russians and the hackers that initially got the documents, because of the speed at which the data moved. Someone in Papadopolous’ Russians group had to get the data from the hackers and check it out superficially to make sure it was what it purported to be, which would take about a week, while the Russian group was baiting the Trump Campaign. The timing works.

I’m also waffling a bit by calling the Russians “Papadopolous’ Russians” because we don’t really know to what degree they were “affiliated” with the Russian intelligence apparatus. Like with the hackers, I am comfortable saying they are “affiliated” because that’s how they presented themselves and even if they weren’t taking orders from Putin (I bet they weren’t, he’s not that much of a micro-manager) they were acting in line with their own perception of Russian affiliation. I believe that many CIA or NSA operations happen without the direct oversight of anyone on the National Security Council and certainly without the direct approval of the president. So, at what point can we say that something is a “US Government operation” versus a “CIA operation” versus a “rogue CIA operation” versus “ultra-nationalists going their own way” (which was basically what the White House portrayed G. Gordon Liddy as doing during Iran/Contra)

Based on the time-line of events there’s another thing we learn, which may explain why the FBI and intelligence community were so reluctant to offer good attribution: they appear to have been standing around figuring all of this out around April/May/June – well in advance of the election, which was in November. Meanwhile, Comey was making mysterious election-influencing remarks about the FBI’s investigations into Clinton’s other emails. Maybe the FBI doesn’t want to talk much about who knew what and when because it’d make it clear that they were incompetent, or playing politics, or incompetently playing politics.

“Likely or even highly likely” sounds pretty bayesian to me. I’m just not comfortable assigning bogo-probabilities to things in order to bolster my confirmation bias.

For an example of the kind of high quality attribution I’d expect from the US’ very expensive intelligence apparatus, you can take a look at Brian Krebs’ attribution of the Mirai Worm: [krebs] or Kaspersky Labs’ attribution of the ‘Equation Group’ malware tree to the NSA [kaspersky] [secur] Even Kaspersky’s attribution depends on external evidence in time, namely that Equation Group’s code was found on NSA’s development server leaks dated before Kaspersky’s attribution – which strongly identifies Equation Group as NSA (or NSA contractors working within NSA).

Papadopolous sounds like the kind of incompetent dumbass that Trump would love. I’m surprised he wasn’t put in charge of some important government agency. (PS: he spent $800,000 on his wardrobe)

Papadopolous also appears to be a “cooperating witness” which may be code for “he wore a wire during some meetings” – it is possible that Mueller has dropped Papadopolous as a card to pull in-suit denials from the next round of indictees.

Unrelated: Papadopolous cheated on at least $75 million in taxes. I wonder whether part of this is going to result in the FBI getting Trump’s tax returns. One thing everyone seems to forget about those: Trump has them but so does the IRS. One need not ask Trump for them. The whole thing around releasing Trump’s taxes is a charade.

Read more: https://freethoughtblogs.com/stderr/2017/10/31/i-now-officially-believe-it-was-russians/#ixzz4x5CnFAkE

Comments Off on I Now Officially Believe it Was Russians

April 20th, 2017

It’s really sad to see that the US military is so desperate and stupid that they had to try showing how capable they are, by showing how capable they aren’t.

Dropping a humongous explosive on a useless target, then defending that action as being useful, is not a demonstration of peerless strength. According to some sources, the ISIS “tunnel complex” may have been occupied by a couple hundred people. So, yeah, it makes a lot of sense to drop a city-killer on them.

But, as a show of power, it begs the question: “weren’t you already incapable of keeping them from building the tunnel complex?” This is the same problem, exactly, that the US had in Vietnam: it could drive its enemies underground using superior air power, and could win every stand-up fight, but – so what? The enemy wasn’t interested in stand-up fights, and could come and go where they wanted. In military terms “come and go where you want” means “control the battlefield.” Dropping GPS-targeted bombs from high altitude is a tacit admission that we can’t send troops in on the ground because they’re not safe.

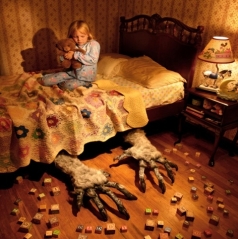

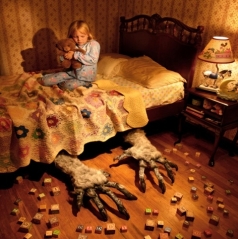

hypothetical Tora Bora complex

To any of us from the Vietnam generation, we immediately recognize this as “body counts” redux. What happens, when you’re losing a war, is the losers (who are supposed to be winning, and who are being paid to win) start coming up with metrics that make it more plausible for them to say they are winning. Body counting inevitably leads to body count inflation, which leads to counting 14 year-old civilian boys as militants, which leads to atrocities. I’m not trying to say “atrocities coming!” because they’re already there and already happening, but there’s always worse: the US military inevitably wants to switch to area bombing, when it has otherwise lost control of a situation. It’s the safest thing you can do that appears to be doing something.

My friend Sazz [stderr] fought around the Vietcong tunnels at Cu Chi. I don’t write “he fought in the tunnels” because only a very small number of Americans went down in them; the rest waited up top to see what happened. One of the things he said was that the tunnel complexes were extensive, but also pretty small and shabby. They weren’t the kind of things Americans would build, with a Burger King and a Starbucks’ 14 stories down, and air conditioning and power generators – they were little hidey holes and they weren’t worth a damn thing to anyone; conqueror or conquered. That’s what the MOAB blew up.

When the invasion of Afghanistan was still brewing, the US marketed the idea that Osama Bin Laden had built gigantic terror complexes under Tora Bora – multi level, hydroelectric powered, and huge. Of course, such complexes did not exist.

Cu Chi tunnels in Vietnam – note the scale

They have never existed, unless you’re thinking about the complexes politicians build to hide from their mistakes. The gigantic MOAB probably collapsed some simple dirt tunnels (because ISIS is sure as hell not tunnelling in stone) The Vietcong at Cu Chi didn’t defend the tunnels when the Americans found them: they left and went elsewhere. The ISIS survivors of the MOAB are already gone to elsewhere, and they’ve added a few recruits from the local population, because the Americans have demonstrated what ruthless assholes we can be.

In Vietnam, the US “tunnel rats” went down into the tunnels with .45s and knives and grenades. The tunnels weren’t very big but US soldiers controlled the ground above the tunnels so they could do that. In Afghanistan, the US has already ceded the landscape to ISIS and the Taliban.

If we don’t control the landscape, we’ve lost the war. Time to be leaving, not time to be dropping experimental ordnance and mugging for the cameras like some kind of reality TV show.

A bit about how the MOAB works: it’s a fuel/air explosive. The idea is to aerosolize something that burns extremely fast (nitrated alcohol and aluminum, for example) and then give it a little while to spread and settle, then you ignite it. The resulting extremely fast combustion destroys everything in the area, and consumes all the oxygen; everything that’s got lungs is dead. It’s bizzare to me that the US is bragging about using fuel/air explosives to do area bombardment, at the same time as it’s complaining about Assad’s regime using Sarin gas. I guess that, because the fuel/air explosive gets in your lungs and explodes, that’s somehow OK compared to Sarin that gets in your nervous system and jams its signalling pathways? Both are horrible deaths that give the victim a brief while in which to contemplate what is coming. It’s as if the American regime is going out of its way to be as hypocritical and vicious as possible.

Dienststelle Marienthal by Magdanz

This is a picture of one of the executive conference rooms in the Dienststelle Marienthal, a “continuity of government” shelter – i.e.: a hole in the ground where politicians thought they could run and hide if they started a nuclear war. [Magdanz]

Whatever the ISIS tunnels were that they wasted the MOAB on, they were not like this.

When I learned about Marienthal, through Magdanz’ amazing book of photos, I tried for years to get permission to visit. Apparently it’s all closed down now, because keeping it in good enough condition for the lights to work, etc, is prohibitively expensive.

Marienthal, conference room

Remember this: This is how politicians expected to live, after they had fled the consequences of their errors, and left the rest of us to burn in nuclear fire.

Read more: http://freethoughtblogs.com/stderr/2017/04/16/the-mother-of-all-bombs/#ixzz4en7PdThX

Comments Off on The Mother of All Bombs

August 16th, 2015

By Marcus J. Ranum.

Those ignorant of history…

William Safire, of the New York Times wrote an article:

(http://www.nytimes.com/2004/02/02/opinion/02SAFI.html also cached here) about “The Farewell Dossier.” (See also on CIA’s unclassified site: http://www.cia.gov/csi/studies/96unclass/farewell.htm) In it, he describes a clandestine operation that mooted a number of Soviet efforts to steal American industrial technology. It’s kind of scary stuff, and I encourage you to read it. A key extract of the article from CIA’s site reads:

American industry helped in the preparation of items to be “marketed” to Line X. Contrived computer chips found their way into Soviet military equipment, flawed turbines were installed on a gas pipeline, and defective plans disrupted the output of chemical plants and a tractor factory. The Pentagon introduced misleading information pertinent to stealth aircraft, space defense, and tactical aircraft.(4) The Soviet Space Shuttle was a rejected NASA design.(5) When Casey told President Reagan of the undertaking, the latter was enthusiastic. In time, the project proved to be a model of interagency cooperation, with the FBI handling domestic requirements and CIA responsible for overseas operations. The program had great success, and it was never detected.

Safire’s article goes a step further and asserts that:

The technology topping the Soviets’ wish list was for computer control systems to automate the operation of the new trans-Siberian gas pipeline. When we turned down their overt purchase order, the K.G.B. sent a covert agent into a Canadian company to steal the software; tipped off by farewell, we added what geeks call a “Trojan Horse” to the pirated product.

“The pipeline software that was to run the pumps, turbines and valves was programmed to go haywire,” writes Reed, “to reset pump speeds and valve settings to produce pressures far beyond those acceptable to the pipeline joints and welds. The result was the most monumental non-nuclear explosion and fire ever seen from space.”

I’m recognized in the computer security community as a detractor of the concept of “information warfare” – mostly because I think that what InfoWar proponents describe as a new form of warfare is really just intelligence operations applied to new technology. In other words, it’s not rocket science, but it may be applied to rocket science, as we see from the CIA article. This is scary and powerful stuff, when you realize that a piece of computer software was deliberately jiggered to blow some unsuspecting oilmen to kingdom come. The geopolitical reasons behind it (they didn’t call it a Cold “War” for nothing) were compelling, but the implications are vast.

…are doomed to repeat it.

Right now, on one hand, we’re spending billions of dollars for this Myth of Homeland Security in the hopes of protecting against terrorists, rogue states, and ideological nutcases. But, on the other hand, corporate America is lining the pockets of executives by driving costs down (and their stock options up) by outsourcing virtually every aspect of non-creative information technology to 3rd world nations. We’ve all heard of the massive code-shops in India, where analysts estimate that 60% of US code is being written today, and as much as 90% will be written by the end of the next 10 years. Do you see the razor blade hidden in the apple? I’m somewhat concerned at the idea of the economic effects of this activity, but I’m terrified by the national security implications. Let’s talk homeland security, shall we?

Last year I got a call from an investment banker in Singapore, who was looking for a programming expert who could do “due diligence” on some software that one of their clients was considering acquiring. The acquirer was a Canadian company, the seller a US company, and the software had been written in Bangalore. After some discussion, I was informed that the software regarded embedded systems and microprocessor controls, etc – specifically, the software was guidance software “of the type” used in the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) – a glide-bomb that uses GPS to home in on its target. We all saw JDAMs in action during the most recent gulf war, and it was a JDAM that accidentally (?) hit the Chinese Embassy during the NATO intervention in Kosovo and bombing of Serbo-Croatia. As someone concerned with national security, I can only ask, “What the F!*K?” Sure, once you have the concept of a JDAM and a GPS chip and some actuators and some software, you can build your own pretty quickly. But why roll out the red carpet?

I’m not a paranoid and I’m not a John Bircher but I sometimes wonder if we’re worried about the wrong things. On one hand we’re spending billions of dollars against a nebulous threat when on the other we’re spending billions of dollars to put ourselves in grave and very real danger. Remember the pipeline explosion? How about a JDAM that doesn’t fly right if the target is within GPS coordinates approximating your national borders? That’s just a simple paranoid fantasy – the reality could be a lot worse. I don’t know. We don’t know. In fact, we can’t know – if we were to try to audit all those jillions of lines of code we’re buying from India, we’d need so many talented programmers it’d be cheaper to write it ourselves in the first place.

Am I becoming a convert to the notion of Information Warfare? I don’t think so. You don’t need to worry about InfoWar if you’re potentially facing a good old-fashioned ass-whupping. When I was a kid I remember I read a science fiction story about a race that was very technologically advanced but were extreme pacifists. They sold weapons to anyone who wanted them – cheap, good, and mighty powerful weapons. Nobody ever attacked them because they assumed that the species actually was holding back all the really good stuff for their own use. Until one day, someone discovered that, in fact, they had been selling all these weapons as a way of population-controlling the other species in the galaxy. So – the other races attacked in force. And every weapon they had promptly blew up.

When pundits talk about the “electronic Pearl Harbor” it’s not going to look like hackers taking down Wall Street and our cell phone networks. It’s going to look like the Farewell Dossier. And I see no sign that we’re doing anything but hastening down the path of maximum vulnerability in the name of short-term profits and pumped-up balance sheets that boost executive bonuses. It’d be a shame to see one of history’s most interesting experiments in governance fail because of short-sightedness and corporate greed.

This is a difficult topic for me to even write about, since outsourcing of US high tech jobs to India has become an election year issue and I’m a former software engineer. I suspect it’s easy to dismiss my thoughts as just sour grapes from a protectionist. In fact, I hope I am completely wrong and that history shows me to be a fool. I really do.

For more on Marcus J. Ranum please visit http://www.ranum.com/

Comments Off on The Farewell Dossier

October 18th, 2012

By Marcus J. Ranum.

Summary: Today’s post by Marcus Ranum discusses Adam Curtis’ brilliant BBC documentary series “The Power of Nightmares”. Cutris deconstructs the dynamic of government as protector against unknown threats. His analysis of how generalized fears of terrorism manipulate the public apply exactly to cyberwar, as well.

“Both [the Islamists and Neoconservatives] were idealists who were born out of the failure of the liberal dream to build a better world. And both had a very similar explanation for what caused that failure. These two groups have changed the world, but not in the way that either intended. Together, they created today’s nightmare vision of a secret, organized evil that threatens the world. A fantasy that politicians then found restored their power and authority in a disillusioned age. And those with the darkest fears became the most powerful.

— The Power of Nightmares, subtitled The Rise of the Politics of Fear, a BBC documentary film series written and produced by Adam Curtis in 2004. Download here.

Contents

- The power of Nightmares

- The Man Who Was Thursday (A Nightmare)

- Anatomy of a Tail-spin

- Curtis’ Words

- For More Information

(1) The Power of Nightmares

Adam Curtis’ brillant documentary series offers a view of the present as a consequence of the search for meaning of the political class. In short: they need something to do, to justify their existence. After all, if everyone were simply happy and comfortable, sooner or later we might wake up and wonder, “what are we giving you guys so much power, for, anyway?” Curtis’ series describes an entirely plausible scenario of what I call an “emergent conspiracy” – a conspiracy that was not planned by a secret committee wearing black velvet capes and meeting in dimly lit corridors of power, but rather a conspiracy that happens and snowballs because it’s convenient and spares the conspirator’s having to deal with the truth.

We can think of emergent conspiracies as a result of co-evolution or co-dependency: all of the parties involved want something, and they stumble around creating a great big whopping lie in order to get it. Then they tell that lie to themselves, and believe it. They act on the lie, and are surprised by the consequences they must, thereafter, live with.

(2) The Man Who Was Thursday (A Nightmare)

“We say that the most dangerous criminal now is the entirely lawless modern philosopher. Compared to him, burglars and bigamists are essentially moral men; my heart goes out to them.

— G.K. Chesterton, The Man Who Was Thursday (1908)

.

The theme of emergent conspiracies is an old one. My favorite example is The Man Who Was Thursday (a Nightmare) by G.K. Chesterton (1908). Gabriel Syme, the hero, is inducted into a secret organization of police dedicated to demolishing and capturing the leadership of the secret organization of anarchists. As the story evolves, we discover that the police and the anarchists depend on eachother for their very existence and the only honest character in the situation is the population (represented by Syme) that is stuck between them, trying to make sense of things. He fails, of course.

Be careful when you fight the monsters, lest you become one.

— Friederich Neitzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, Aphorism 146 (1886)

What Curtis’ analysis adds that is so brilliant is the observation that:

[T]he person with the most vivid imagination becomes the most powerful.

This is exactly what has happened with cyberwar punditry as well as counter-terrorism punditry. I would slightly modify Curtis’ words, if I could, replacing “vivid” with “horrible.”

(3) Anatomy of a Tail-spin

When the cyberwar meme first broke on the scene in the mid 1990s, the defense/intelligence complex was looking for a new enemy, a new mission, following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Just as the islamic jihadist stepped into the role of boogeyman in the counterterror arena, cyberwar became the computer security world’s boogeyman.

It started small: Winn Schwartau’s horrible imaginings (see Wikipedia) painted a scary, albeit ludicrously improbable, world of cyberwar, which scared some people into allocating money to defend themselves against this new threat. Seeing that money was being allocated, cyberwar proponents banged the fear-drums a little harder — and, more money was allocated.

Suddenly, the fear/uncertainty/doubt feedback loop was fully formed and peaked in 2010, when we witnessed gigantic sums of money (mostly in classified budgets) being allocated for cyberwars that so far hadn’t happened. The expenditures for offensive cyberwar had to be justified, so the trigger was pulled on Stuxnet et al – and now the game is fully afoot. In order to keep the money-valve jammed wide open, pundits vie with their willing victims in an effort to scare them with ever-worsening nightmares.

The pundit with the most nightmarish imagination is the most powerful, and the consulting firm they work for makes the most money.

(4) Curtis’ Words

The following is extracted from the transcript of The Power of Nightmares:

VO: But those dreams collapsed, and politicians like Tony Blair became more like managers of public life, their policies determined often by focus groups. But now, the war on terror allowed politicians like Blair to portray a new, grand vision of the future. But this vision was a dark one of imagined threats, and a new force began to drive politics: the fear of an imagined future.

[ CUT , INTERIOR, TONY BLAIR ADDRESSING AUDIENCE ]

TONY BLAIR : Not a conventional fear about a conventional threat, but the fear that one day these new threats of weapons of mass destruction, rogue states, and international terrorism combine to deliver a catastrophe to our world. And then the shame of knowing that I saw that threat, day after day, and did nothing to stop it.

[ CUT , ANOTHER ADDRESS ]

BLAIR : It may not erupt and engulf us this month or next, perhaps not even this year or next …

[ CUT , CLOSE-UP ON TONY BLAIR , SPEAKING TO INTERVIEWER BEFORE STUDIO AUDIENCE ]

BLAIR : I just think these—these dangers are there, I think that it’s difficult sometimes for people to see how they all come together—I think that it’s my duty to tell it to you if I really believe it, and I do really believe it. I may be wrong in believing it, but I do believe it.

[ CUT , EXTERIOR , MOONLIT , DARK CITY SKYLINE ]

VO: What Blair argued was that faced by the new threat of a global terror network, the politician’s role was now to look into the future and imagine the worst that might happen and then act ahead of time to prevent it. In doing this, Blair was embracing an idea that had actually been developed by the Green movement: it was called the “precautionary principle.” Back in the 1980s, thinkers within the ecology movement believed the world was being threatened by global warming, but at the time there was little scientific evidence to prove this. So they put forward the radical idea that governments had a higher duty: they couldn’t wait for the evidence, because by then it would be too late; they had to act imaginatively, on intuition, in order to save the world from a looming catastrophe.

[ CUT , INTERIOR , MEETING ROOM ]

DURODIE : In essence, the precautionary principle says that not having the evidence that something might be a problem is not a reason for not taking action as if it were a problem. That’s a very famous triple-negative phrase that effectively says that action without evidence is justified. It requires imagining what the worst might be and applying that imagination upon the worst evidence that currently exists.

[ CUT , INTERIOR , HALL ; ANGLE ON TONY BLAIR ADDRESSING STATE FUNCTION ]

BLAIR : Would Al Qaeda buy weapons of mass destruction if they could? Certainly. Does it have the financial resources? Probably. Would it use such weapons? Definitely.

[ CUT , INTERIOR , MEETING ROOM ]

DURODIE : But once you start imagining what could happen, then—then there’s no limit. What if they had access to it? What if they could effectively deploy it? What if we weren’t prepared? What it is is a shift from the scientific, “what is” evidence-based decision making to this speculative, imaginary, “what if”-based, worst case scenario.

[ CUT , EXTERIOR , CAMP X-RAY , Guantánamo Bay, Cuba ]

VO: And it was this principle that now began to shape government policy in the war on terror. In both America and Britain, individuals were detained in high-security prisons, not for any crimes they had committed, but because the politicians believed—or imagined—that they might commit an atrocity in the future, even though there was no evidence they intended to do this. The American attorney general explained this shift to what he called the “paradigm of prevention.”

[ CUT , INTERIOR , HEARING ROOM , UNITED STATES CONGRESS ]

ASHCROFT : We had to make a shift in the way we thought about things, so being reactive, waiting for a crime to be committed, or waiting for there to be evidence of the commission of a crime didn’t seem to us to be an appropriate way to protect the American people.

Curtis cuts brilliantly to the heart of the matter: because it hasn’t actually happened, it’s scarier than if it did. Thus, increasingly powerful reactions are justified against largely imaginary threats.

At what point will the US or Israel beat the war-drums against some other country (probably Iran) because they offer the potential threat of someday inflicting nightmarishly imagined cyber-devastation?

[ CUT , INTERIOR , OFFICE ]

DAVID COLE : Under the preventive paradigm, instead of holding people accountable for what you can prove that they have done in the past, you lock them up based on what you think or speculate they might do in the future. And how—how can a person who’s locked up based on what you think they might do in the future disprove your speculation? It’s impossible, and so what ends up happening is the government short-circuits all the processes that are designed to distinguish the innocent from the guilty because they simply don’t fit this mode of locking people up for what they might do in the future.

I challenge the Iranians to prove to our satisfaction that they are not planning cyberstrikes on our power-grid that will knock us back to the Late Cretaceous period.

[ CUT , INTERIOR , RESTAURANT ]

DAVID JOHNSTON , INTELLIGENCE SPECIALIST , NEW YORK TIMES : You’ll hear about meetings where terrorist matters are discussed in the intelligence community, and always the person with the most dire assessment, the person with the—who has the, kind of, the strongest sense that something should be done will frequently carry the day at meetings. We thus believe the most dire estimate of what could happen here. The sense of disbelief has vanished.

Voices of sanity must be heard; they will sound like skeptics and attempts will be made to dismiss them as mere nay-sayers.

Syme was dumb for an instant. Then he rose to his feet erect, like an insulted man, and thrust the chair away from him.

“Yes,” he said in a voice indescribable, “you are right. I am afraid of him. Therefore I swear by God that I will seek out this man whom I fear until I find him, and strike him on the mouth. If heaven were his throne and the earth his footstool, I swear that I would pull him down.”

“How?” asked the staring Professor. “Why?”

“Because I am afraid of him,” said Syme; “and no man should leave in the universe anything of which he is afraid.”

– G.K. Chesterton, “The Man Who Was Thursday”

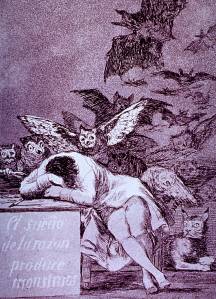

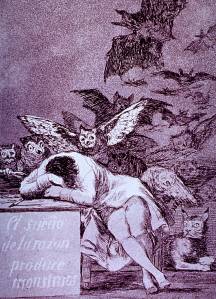

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, Goya, 1856

Check this article at: http://fabiusmaximus.com/2012/08/31/42830/

No Comments "

Evidence collected from other systems that matches the understanding of the attackers’ actions: This element of the attribution is still thinner than I’d like but the timing on the documents that Wikileaks eventually released matches the story of how the documents were compromised, shopped around between Papadopolous/the Trump Campaign and Wikileaks. I don’t think we need to see the various emails going back and forth; all the information Papadopolous has provided is congruent with Wikileaks’ version and the accounts of the DNC break-in from Crowdstrike. I think Crowdstrike could have provided better information but almost certainly were told not to by the FBI who were keeping that information in order to strengthen their own attribution if congruent pieces of the puzzle later emerged. In fairness to the FBI I will note that having whatever information Crowdstrike provided to them kept secret probably made it harder for Papadopolous to lie about any of the timing of these events and subsequent emails. So, while I complain about the FBI’s actions, I understand them.

Evidence collected from other systems that matches the understanding of the attackers’ actions: This element of the attribution is still thinner than I’d like but the timing on the documents that Wikileaks eventually released matches the story of how the documents were compromised, shopped around between Papadopolous/the Trump Campaign and Wikileaks. I don’t think we need to see the various emails going back and forth; all the information Papadopolous has provided is congruent with Wikileaks’ version and the accounts of the DNC break-in from Crowdstrike. I think Crowdstrike could have provided better information but almost certainly were told not to by the FBI who were keeping that information in order to strengthen their own attribution if congruent pieces of the puzzle later emerged. In fairness to the FBI I will note that having whatever information Crowdstrike provided to them kept secret probably made it harder for Papadopolous to lie about any of the timing of these events and subsequent emails. So, while I complain about the FBI’s actions, I understand them.