Posts by thedailyjournalist:

How Squash Agriculture Spread Bees in Pre-Columbian North America

July 2nd, 2016

The Daily Journalist.

Using genetic markers, researchers have for the first time shown how cultivating a specific crop led to the expansion of a pollinator species. In this case, the researchers found that the spread of a bee species in pre-Columbian Central and North America was tied to the spread of squash agriculture.

“We wanted to understand what happens when the range of a bee expands,” says Margarita López-Uribe, a postdoctoral researcher at North Carolina State University and lead author of a paper describing the work. “What does that mean for its genetic variability? And if the genetic variability declines, does that harm the viability of the species?”

To explore these questions, researchers looked at the squash bee (Peponapis pruinosa), which is indigenous to what is now central Mexico and the southwestern United States. Squash bees are specialists, collecting pollen solely from the flowers of plants in the genus Cucurbita, such as squash, zucchini and pumpkins.

Before contact with Europeans, native American peoples had begun cultivating Cucurbitacrops. Over time, these agricultural practices spread to the north and east.

“We wanted to know whether P. pruinosa spread along with those crops,” López-Uribe says.

To find out, researchers looked at DNA from squash bee individuals, collected from throughout the species’ range. P. pruinosa can now be found from southern Mexico to California and Idaho in the west, and from Georgia in the southeast to Quebec in the north.

By assessing genetic markers in each bee’s DNA, the researchers could identify genetic signatures associated with when and where the species expanded.

For example, the researchers found that P. pruinosa first moved from central Mexico into what is now the Midwestern United States approximately 5,000 years ago, before expanding to the East Coast some time later.

The researchers also found that genetic diversity decreased depending how “new” the species was to a given territory. For example, genetic diversity of squash bees in Mexico was greater than the diversity in the Midwest; and diversity in the Midwest was greater than that of populations on the East Coast.

Given the declining genetic variability, researchers expected to see adverse effects in the “newer” populations of P. pruinosa.

They didn’t.

“We were specifically expecting to see an increased rate of sterile males in populations with less genetic variability, and we didn’t find that,” López-Uribe says. “But we did find genetic ‘bottlenecks’ in all of the populations – even in Mexico.

“Because P. pruinosa makes its nests in the ground near squash plants, we think modern farming practices – such as mechanically tilling the soil – is causing the species to die out in local areas,” López-Uribe says. “And we think that is causing these more recent genetic bottlenecks.

“I’m hoping to work on this question in the near future, because it’s important to helping understand the relevant bee’s population dynamics in modern agricultural systems, as well as what it may mean for Cucurbita crops,” López-Uribe says.

Comments Off on How Squash Agriculture Spread Bees in Pre-Columbian North America

Sergei Shoigu: Military-technical co-op between Russia, Azerbaijan of strategic nature

July 1st, 2016

The Daily Journalist.

He made the remarks during the talks with Azerbaijans Defense Minister Zakir Hasanov on the sidelines of the 70th meeting of the Council of Defense Ministers of the CIS in Moscow June 15.

He noted that the two countries enjoy high-level cooperation in all fields, particularly in the military sphere.

In turn, Minister Hasanov thanked his Russian counterpart for the reception and conveyed to him the greetings of Azerbaijani President, Supreme Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces Ilham Aliyev.

Hasanov praised the cooperation between Azerbaijan and Russia in the military sphere and invited his Russian counterpart to Azerbaijan.

Then, the talks were continued behind closed doors.

Comments Off on Sergei Shoigu: Military-technical co-op between Russia, Azerbaijan of strategic nature

A 6,000 Year Old Telescope Without A Lens – Prehistoric Tombs Enhanced Astronomical Viewing

July 1st, 2016The Daily Journalist.

Astronomers are exploring what might be described as the first astronomical observing tool, potentially used by prehistoric humans 6,000 years ago. They suggest that the long, narrow entrance passages to ancient stone, or ‘megalithic’, tombs may have enhanced what early human cultures could see in the night sky, an effect that could have been interpreted as the ancestors granting special power to the initiated. The team present their study at the National Astronomy Meeting, being held this week in Nottingham.

Photographs of the megalithic cluster of Carregal do Sal: a) Dolmen da Orca, a typical dolmenic structure in western Iberia; b) view of the passage and entrance while standing within the dolmens’ chamber: the ‘window of visibility’; c) Orca de Santo Tisco, a dolmen with a much smaller passage or corridor.

The team’s idea is to investigate how a simple aperture, for example an opening or doorway, affects the observation of slightly fainter stars. They focus this study on passage graves, which are a type of megalithic tomb composed of a chamber of large interlocking stones and a long narrow entrance. These spaces are thought to have been sacred, and the sites may have been used for rites of passage, where the initiate would spend the night inside the tomb, with no natural light apart from that shining down the narrow entrance lined with the remains of the tribe’s ancestors.

These structures could therefore have been the first astronomical tools to support the watching of the skies, millennia before telescopes were invented. Kieran Simcox, a student at Nottingham Trent University, and leading the project, comments: “It is quite a surprise that no one has thoroughly investigated how for example the colour of the night sky impacts on what can be seen with the naked eye.”

The view towards the east from the Carregal do Sal megalithic cluster, at dawn at the end of April around 4,000 BCE, as reconstructed using a Digital Elevation Model and Stellarium. Aldebaran, the last star to rise before the sun, is rising directly above Serra da Estrela, the “mountain range of the star”.

The project targets how the human eye, without the aid of any telescopic device, can see stars given sky brightness and colour. The team intend to apply these ideas to the case of passage graves, such as the 6,000 year old Seven-Stone Antas in central Portugal. Dr Fabio Silva, of the University of Wales Trinity Saint David, explains that, “the orientations of the tombs may be in alignment with Aldebaran, the brightest star in the constellation of Taurus. To accurately time the first appearance of this star in the season, it is vital to be able to detect stars during twilight.”

The first sighting in the year of a star after its long absence from the night sky might have been used as a seasonal marker, and could indicate for example the start of a migration to summer grazing grounds. The timing of this could have been seen as secret knowledge or foresight, only obtained after a night spent in contact with the ancestors in the depths of a passage grave, since the star may not have been observable from outside. However, the team suggest it could actually have been the result of the ability of the human eye to spot stars in such twilight conditions, given the small entrance passages of the tombs.

The yearly National Astronomy Meetings have always had some aspects of cultural astronomy present in their schedules. This is the third year running where a designated session is included, exploring the connection between the sky, societies, cultures and people throughout time. The session organiser over the past three years, Dr Daniel Brown of Nottingham Trent University, says: “It highlights the cultural agenda within astronomy, also recognised by the inclusion of aspects of ancient astronomy within the GCSE astronomy curriculum.”

Comments Off on A 6,000 Year Old Telescope Without A Lens – Prehistoric Tombs Enhanced Astronomical Viewing

Centuries-Old Shipwreck Discovered Off NC Coast

June 30th, 2016

The Daily Journalist.

Scanning sonar from a scientific expedition has revealed the remains of a previously unknown shipwreck more than a mile deep off the North Carolina coast. Artifacts on the wreck indicate it might date to the American Revolution.

Marine scientists from Duke University, North Carolina State University and the University of Oregon discovered the wreck on July 12 during a research expedition aboard the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) research ship Atlantis.

The research vessel Atlantis with the submersible Alvin hanging off its stern.

They spotted the wreck while using WHOI’s robotic autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) Sentry and the manned submersible Alvin. The team had been searching for a mooring that was deployed on a previous research trip in the area in 2012.

Among the artifacts discovered amid the shipwreck’s broken remains are an iron chain, a pile of wooden ship timbers, red bricks (possibly from the ship cook’s hearth), glass bottles, an unglazed pottery jug, a metal compass, and another navigational instrument that might be an octant or sextant.

The wreck appears to date back to the late 18th or early 19th century, a time when a young United States was expanding its trade with the rest of the world by sea.

“This is an exciting find, and a vivid reminder that even with major advances in our ability to access and explore the ocean, the deep sea holds its secrets close,” said expedition leader Cindy Van Dover, director of the Duke University Marine Laboratory.

“I have led four previous expeditions to this site, each aided by submersible research technology to explore the sea floor — including a 2012 expedition where we used Sentry to saturate adjacent areas with sonar and photo images,” Van Dover said. “It’s ironic to think we were exploring within 100 meters of the wreck site without an inkling it was there.”

“This discovery underscores that new technologies we’re developing to explore the deep-sea floor yield not only vital information about the oceans, but also about our history,” said David Eggleston, director of the Center for Marine Sciences and Technology (CMAST) at NC State and one of the principal investigators of the science project.

Photo of the remnants of the shipwreck in the seabed off of the North Carolina coast.

After discovering the shipwreck, Van Dover and Eggleston alerted NOAA’s Marine Heritage Program of their find. The NOAA program will now attempt to date and identify the lost ship.

Bruce Terrell, chief archaeologist at the Marine Heritage Program, says it should be possible to determine a date and country of origin for the wrecked ship by examining the ceramics, bottles and other artifacts.

“Lying more than a mile down in near-freezing temperatures, the site is undisturbed and well preserved,” Terrell said. “Careful archaeological study in the future could definitely tell us more.”

James Delgado, director of the Marine Heritage Program, notes that the wreck rests along the path of the Gulf Stream, which mariners have used for centuries as a maritime highway to North American ports, the Caribbean, the Gulf of Mexico and South America

“The find is exciting, but not unexpected,” he said. “Violent storms sent down large numbers of vessels off the Carolina coasts, but few have been located because of the difficulties of depth and working in an offshore environment.”

Bob Waters of WHOI piloted Alvin to the site of the newly discovered shipwreck after Sentry’s sonar-scanning system detected a dark line and a diffuse, dark area which they thought could be the missing scientific mooring. Bernie Ball of Duke and Austin Todd of NC State were aboard Alvin as science observers.

The expedition has been focused on exploring the ecology of deep-sea methane seeps along the East Coast. Van Dover is a specialist in the ecology of deep-sea ecosystems that are powered by chemistry rather than sunlight, and Eggleston studies the ecology of organisms that live on the seafloor.

“Our accidental find illustrates the rewards — and the challenge and uncertainty — of working in the deep ocean,” Van Dover said. “We discovered a shipwreck but, ironically, the lost mooring was never found.”

Comments Off on Centuries-Old Shipwreck Discovered Off NC Coast

Ancient Burial Rituals Prove You Can Take It With You… And What You Take Says A Lot

June 29th, 2016The Daily Journalist.

Death is inevitable, but what death shows us about the social behaviors of the living is not.

And recent University of Cincinnati research examining the ancient bereavement practices from the the Central Apulian region in pre-Roman Italy helps shed light on economic and social mobility, military service and even drinking customs in a culture that left no written history.

This image shows a 4th century assemblages with fine Greek vases, banquet implements and metal weapons.

For instance, by focusing on the logistics of burials, treatment of deceased bodies and grave contents dating from about 525-200 BC, UC Classics doctoral student Bice Peruzzi found indication of strong social stratification and hierarchy. She also found indications of the commonality of military service since men’s tombs of the era routinely contained metal weaponry lying across or near the skeletal remains.

Another example: in the second half of the 4th century, an impressive increase in the number of tombs over a 50-year period indicates newer social groups gaining access to ceremonial burials that included use of the space by the living for a brief period of dancing and banqueting.

“After going through volumes of collected material, I realized that there was so much more that could be said about what was happening in the development of this particular culture,” says Peruzzi. “In spite of having no written history, I was able to distinguish three different periods and then connect them to the larger Mediterranean history to see how their society changed.”

She just presented her findings on these funerary practices in their broader historical context at the 2016 Archaeological Institute of America/Society for Classical Studies Annual Meeting in San Francisco.

WINE, WOMEN, AND WAR

Because a major Greek influence on this region had already existed, Preuzzi was not surprised to find valuable Greek vases and artifacts among the Apulian tomb contents from the 1st period (525-350). The finely detailed imagery on these vases often focused on women engaged in everyday activities such as courting, processions and wine offerings, which opened interesting questions about the role of women in those communities.

Other tomb contents ranged from wine cups and feasting sets to metal weaponry among the male tombs. And according to Peruzzi, the objects were chosen intentionally and purposefully placed during funerary rituals to project a personal message about the deceased’s role in the community.

Peruzzi also found remarkable evidence for tomb reuse. In a curious and calculated fashion, several tombs had been reopened showing older bones and artifacts pushed to the side to make way for a newer body and its contents, possibly creating a link between the present funeral and the memory of the past one.

“The care in displaying the artifacts in these tombs is striking, especially considering that the objects could have been visible only during the brief period when the tomb was open,” says Peruzzi. “This gives the impression that during Period 1 the tomb was conceived not only as the final resting place of the deceased, but almost as the stage for dancing and a burial performance.”

A WIDENING WORLD

Throughout Period 2 (350-300), Peruzzi found that general trends in burial ceremony continued to focus around themes of banquet, war and women. But the increase in the number of tombs by this time strongly indicated that newer social groups were gaining access to this banquet-type funeral.

But much like in modern society, the elite now showed signs of breaking away from former trends to distinguish themselves from the general population. Items inside their tombs now included many new large Apulian red figure vases with generic iconography and repetitive designs.

“In this period we also find occasional assemblages containing very large vases with sophisticated iconographies that portray Greek tragedies,” says Peruzzi. “Scholars attribute this shift in taste to Greek influence, in particular the fascination with the military victories of Alexander the Great.

“The new growth of specific burial sites to the detriment of others in addition to newly constructed walls surrounding the communities also indicates a general movement toward urbanization in Period 2.”

NEW NEIGHBORHOODS

Now entering into an era of great transformation, Period 3 (300-200) began to shift from large numbers of individual tombs to larger chamber tombs — often containing whole families — with a new emphasis on elaborate funerary architecture around the tombs.

And as for grave site partying, not so much. The iconography of female beauty, happiness in the afterlife and piety toward the dead formerly found on vase designs had changed.

Instead, grave goods now contained bottomless, undecorated ceramics were created simply to be symbolic of the older communal feasting. And metal weaponry was now replaced by a small number of fibulae, hairpins and other personal ornaments.

With new defensive walls now surrounding larger communities and more sophisticated governmental systems developing, Peruzzi found the new class of elites shifting away from elaborate burial ceremonies to using different arenas to negotiate their status.

“By looking at artifacts in their archaeological and social context, I was able to illustrate changes never before recognized,” says Peruzzi. ” From the emergence of new social groups at the end of the 6th century B.C. to the gradual urbanization and separation of “ethnic” groups during the 3rd century B.C., the evolution of funerary practices can be successfully used to highlight major transformations in the social organization of Central Apulia communities.”

Comments Off on Ancient Burial Rituals Prove You Can Take It With You… And What You Take Says A Lot

Resolving The Mystery of Uterine Vellum Used in First Pocket Bibles

June 28th, 2016The Daily Journalist.

A simple PVC eraser has helped an international team of scientists led by bioarchaeologists at the University of York to resolve the mystery surrounding the tissue-thin parchment used by medieval scribes to produce the first pocket Bibles.

Thousands of the Bibles were made in the 13th century, principally in France but also in England, Italy and Spain. But the origin of the parchment — often called ‘uterine vellum’ — has been a source of long standing controversy.

Use of the Latin term abortivum in many sources has led some scholars to suggest that the skin of fetal calves was used to produce the vellum. Others have discounted that theory, arguing that it would not have been possible to sustain livestock herds if so much vellum was produced from fetal skins. Older scholarship even argued that unexpected alternatives such as rabbit or squirrel may have been used, while some medieval sources suggest that hides must have been split by hand through use of a lost technology.

A multi-disciplinary team of researchers, led by Dr Sarah Fiddyment and Professor Matthew Collins of the BioArCh research facility in the Department of Archaeology at York, developed a simple and objective technique using standard conservation treatments to identify the animal origin of parchment.

The non-invasive method is a variant on ZooMS (ZooArchaeology by Mass Spectrometry) peptide mass fingerprinting but extracts protein from the parchment surface simply by using electrostatic charge generated by gentle rubbing of a PVC eraser on the membrane surface.

The research, which is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), involved scientists and scholars from France, Belgium, Denmark, Ireland, the USA and the UK. They analysed 72 pocket Bibles originating in France, England and Italy, and 293 further parchment samples from the 13th century. The parchment samples ranged in thickness from 0.03 – 0.28mm.

Dr Fiddyment said: “We found no evidence for the use of unexpected animals; however, we did identify the use of more than one mammal species in a single manuscript, consistent with the local availability of hides.

“Our results suggest that ultrafine vellum does not necessarily derive from the use of abortive or newborn animals with ultra-thin skin, but could equally reflect a production process that allowed the skins of maturing animals of several species to be rendered into vellum of equal quality and fineness.”

The research represents the first use of triboelectric extraction of protein from parchment. The method is non-invasive and requires no specialist equipment or storage. Samples can be collected without need to transport the artifacts — researchers can sample when and where possible and analyse when required.

Bruce Holsinger, Professor of English and Medieval Studies at the University of Virginia and the initial humanities collaborator on the project, said: “The research team includes scholars and collaborators from over a dozen disciplines across the laboratory sciences, the humanities, the library and museum sciences–even a parchment maker. In addition to the discoveries we’re making, what I find so exciting about this project is its potential to inspire new models for broad-based collaborative research across multiple paradigms. We think together, model together, write together.”

Alexander Devine, of the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies at the University of Pennsylvania, said: “The bibles produced on a vast scale throughout the 13th century established the contents and appearance of the Christian Bible familiar to us today. Their importance and influence stem directly from their format as portable one-volume books, made possible by the innovative combination of strategies of miniaturization and compression achieved through the use of extremely thin parchment. The discoveries of this innovative research therefore enhance our understanding of how these bibles were produced enormously, and by extension, illuminate our knowledge of one of the most significant text technologies in the histories of the Bible and of Western Christianity.”

Professor Collins added: “The level of access we have achieved highlights the importance of this technique. Without the eraser technique we could not have extracted proteins from so many parchment samples. Further, with no evidence of unexpected species, such as rabbit or squirrel, we believe that ‘uterine vellum’ was often an achievement of technological production using available resources.”

Since finishing the work, parchment conservator Ji í Vnouček, a co-author on the paper, has used this knowledge to recreate parchment similar to ‘uterine vellum’ from old skins. He said: “It is more a question of using the right parchment making technology than using uterine skin. Skins from younger animal are of course optimal for production of thin parchment but I can imagine that every skin was collected, nothing wasted.”

Comments Off on Resolving The Mystery of Uterine Vellum Used in First Pocket Bibles

The First Big Bird, Horus Of Egypt As Never Seen Before

June 27th, 2016The Daily Journalist.

‘That’s one weird looking bird,’ grinned an American student on one of my tours of the Ancient Egypt and Sudan Department study collection for university students last year.

And to Egyptology students he is. And to students of Classical Archaeology too. But that’s rather the point. Roman Egypt (30 BC-AD 642) witnessed some of the most interesting, innovative and transformative combinations of traditions in the ancient world.

The god sits casually on his throne, one sandal-clad foot forward, his knees apart and draped in a garment. From the waist down, he could be any of a number of senior Olympian deities, or Roman emperors masquerading as such. He wears a feathered mail armour shirt that ends just above his elbows. His arms, now broken off, would have held symbols of power, perhaps an orb and sceptre. His cloak, pushed back over his shoulders, is fastened with a circular broach. From the waist up, his costume belongs to military deities and, especially, Roman emperors, who were also worshipped in temples dedicated to them throughout the empire. The head, however, places us firmly in an Egyptian context.

It’s Horus, the sun god and divine representative of the living king in ancient Egyptian tradition. His head is that of a falcon, rendered in naturalistic style with the bird’s distinctive facial markings articulated by the carving and also traces of paint. His eyes, however, are strangely human; instead of being placed on the sides of the head, like any ‘real’ bird, they are frontal, and his incised pupils tilt his gaze upward. In an imaginative turn, the feathers of the falcon’s neck blend into the scales of the mail shirt. In the top of his head is a hole, into which a (probably metal) crown once fit.

Big Bird, as I think of him, has been off public display since 1996 when the gallery he was formerly displayed in was reconfigured to create the Great Court. Since I arrived at the Museum in 2007, he’s been the culmination of my tours for university students, giving us the opportunity to explore cultural identity through different kinds of objects from Roman Egypt. We look at magical papyri written in Egyptian and Greek, with some of the Egyptian words written in Old Coptic, that is, the Egyptian language written in Greek script. Why the glosses of Egyptian words in Greek script? Because in magical spells it was very important to say the words correctly or else the spell wouldn’t work. And Greek script, unlike Egyptian, represented the vowels ensuring that the words said aloud were accurately pronounced at a time when literacy in Egyptian scripts was on the wane. We also look at mummy portraits belonging firmly in the Roman tradition of individualised commemorative portraiture, but made for the specific purpose of placing over the face of a mummy, a feature that belongs unmistakably to Egyptian funerary practice. We see the same combination of traditions in this limestone sculpture of Horus and other contemporary depictions.

The opportunity to get the sculpture on public display arose last year when the Gayer-Anderson cat was scheduled to travel to Paris, then Shetland, for exhibition. Big Bird would get his very own case at the top of a ramp, amid other sculpture more readily identifiable as ‘Egyptian’ in the British Museum Egyptian Sculpture Gallery.

While preparing the display, we also had a chance to identify some of the pigments that are apparent to the naked eye: his yellow arms, black pupils and ‘eye-liner,’ garments in two different shades of green, and his red and black throne. Using an innovative imaging technique, we were also able to detect the pigment used for his armour, and it turned out to be one of the most valued pigments of the ancient world,Egyptian blue.

Although no longer apparent to the naked eye, it shows up in visible-induced luminescence imaging by British Museum scientist, Joanne Dyer. In addition to the strange (to us) combination of Graeco-Roman-Egyptian elements, he would also have been rather garishly painted.

Horus – I should really stop thinking of him as Big Bird – will not go back into the study collection when the Gayer-Anderson cat returns, but instead join a touring exhibition on the Roman Empire which will give visitors to the exhibition in locations including Bristol, Norwich and Coventry, that is, in former Roman Britain, an opportunity to see a selection of objects from Antinoupolis and other cities from the former empire’s southern frontier, Roman Egypt.

For their collaboration and enthusiasm, I thank Joanne Dyer, Tracey Sweek, Michelle Hercules, Antony Simpson, Susan Holmes, Paul Goodhead, Robert Frith, Evan York, Emily Taylor and Kathleen Scott from the American Research Center in Egypt

The sculpture of Horus will be on display until 10 December 2012, in Room 4

Comments Off on The First Big Bird, Horus Of Egypt As Never Seen Before

Kurdistan Site Reveals Evolution towards the First Cities of Mesopotamia

June 26th, 2016

The Daily Journalist.

A Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) campaign at the site of Gird Lashkir, in Iraq, reveals the evolution from the first farming societies to the consolidation of the first cities of Mesopotamia. The director of the research, UAB professor Miquel Molist, qualifies the area as an archaeological site of exceptional potential, given that there is no other similar site with so many occupancies in the area.

Researchers from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona have revealed the latest archaeological discoveries on the origins and consolidation of the first farming societies in Upper Mesopotamia, in Iraqi Kurdistan.

The research is the result of a project conducted by an interdisciplinary team under the leadership of professors Anna Gómez Bach and Miquel Molist, from the UAB Department of Prehistory. The area had been closed off since the 1990s to archaeological research and the UAB is the only research team from Spain participating in the dig.

After many years working in Syria and Turkey, where all work was halted due to the military instability of the area, the research team coordinated by professor Miquel Molist continues to study the origins and consolidation of the first farming societies, in this case in the most eastern part of Upper Mesopotamia.

Iraqi Kurdistan is one of the most interesting regions of the Middle East, given that since the 1990s and until three years ago no archaeological research could be conducted there, making it a new geographic and historical site in which to conduct archaeological studies.

Currently there are several European and American teams focusing on research in the area, such as the UAB team, thanks to a collaboration agreement between the UAB and the Salahaddin University-Erbil. The first campaign was conducted in autumn 2015 and the second took place in May and in the first week of June 2016.

The Gird Lashkir site is an archaeological tell with exceptional potential, with some 14 metres of sediments and a surface of approximately 4 hectares occupied by ancient populations. It is located close to the temporary river of Wadi Kasnazan and the cities of Kasnazan and Banaslawa, pertaining to the current capital of Kurdistan, Erbil (northern Iraq).

The archaeological dig has revealed a series of occupancies which go from the Neolithic period to the first millennium BCE.

Over 150 m2 have been uncovered, which distributed along the slopes of the tell, have allowed researchers to discover well conserved architectural remains of specialised buildings, personal houses and working areas located in exterior areas.

Researchers were able to differentiate between the more recent occupancies, located in the higher part of the tell and dating from the historic Neo-Assyrian period (until the end of the second millennium BCE). Several objects discovered from this era stand out and could indicate that one of the buildings was used as a warehouse, and could be linked to the exchange of goods.

The most ancient period, discovered on site this latest campaign, is an occupancy from the Uruk period (ca. 4000 to 3100 BCE), in one of the deepest digs conducted at some 4 metres below current ground level. Remains were also recovered from the Neolithic’s Ubaid and Halaf periods (6000 to 4500 BCE).

The evaluation of the discoveries made at this site is very positive. First from a scientific viewpoint, given that there are no sites with an occupancy similar to the one in the area of Erbil and because it allows to discover the evolution of the settlement in the western plain of northern Kurdistan. The good conservation of the remains and the importance of the objects found confirm the potential of the settlement as a historical source of the first cities of Mesopotamia.

The UAB research team is the only one from Spain participating in the new archaeological research activities in Iraqi Kurdistan, and has established cooperation and heritage development relationships with local institutions (specifically with the Erbil Museum and the Directorate General of Antiquities).

After the dig campaign, researchers are beginning to work in the laboratory to conduct an in-depth study of all the material elements discovered and carry out archaeometric analyses with radiocarbon dating, as well as determine the raw materials of the objects.

Work at the site will continue in 2017 with the final restoration of the most significant objects which will be exposed at the Archaeological Museum of Erbil.

The Gird Lashkir project, initiated in 2015 by the team at the Prehistoric Middle Eastern Archaeology Seminar (Department of Prehistory of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona) with the collaboration of the Directorate General of Antiquities of Kurdistan and the Salahaddin University-Erbil, was also financed by the Directorate General for Fine Arts and Cultural Goods, and for Archives and Libraries of the Spanish Ministry for Education, Culture and Sports.

Comments Off on Kurdistan Site Reveals Evolution towards the First Cities of Mesopotamia

Rice Basket Study Rethinks Roots Of Human Culture

June 24th, 2016

The Daily Journalist.

A new study from the University of Exeter has found that teaching is not essential for people to learn to make effective tools.

The results counter established views about how human tools and technologies come to improve from generation to generation and point to an explanation for the extraordinary success of humans as a species. The study reveals that although teaching is useful, it is not essential for cultural progress because people can use reasoning and reverse engineering of existing items to work out how to make tools.

(1)

Although teaching is useful, it is not essential for cultural progress

The capacity to improve the efficacy of tools and technologies from generation to generation, known as cumulative culture, is unique to humans and has driven our ecological success. It has enabled us to inhabit the coldest and most remote regions on Earth and even have a permanent base in space. The way in which our cumulative culture has boomed compared to other species however remains a mystery.

It had long been thought that the human capacity for cumulative culture was down to special methods of learning from others – such as teaching and imitation – that enable information to be transmitted with high fidelity.

To test this idea, the researchers recreated conditions encountered during human evolution by asking groups of people to build rice baskets from everyday materials. Some people made baskets alone, while others were in ’transmission chain’ groups, where each group member could learn from the previous person in the chain either by imitating their actions, receiving teaching or simply examining the baskets made by previous participants.

Teaching produced the most robust baskets but after six attempts all groups showed incremental improvements in the amount of rice their baskets could carry.

Dr Alex Thornton from the Centre for Ecology and Conservation at the University of Exeter’s Penryn Campus in Cornwall said: “Our study helps uncover the process of incremental improvements seen in the tools that humans have used for millennia. While a knowledgeable teacher clearly brings important advantages, our study shows that this is not a limiting factor to cultural progress. Humans do much more than learn socially, we have the ability to think independently and use reason to develop new ways of doing things. This could be the secret to our success as a species.”

The results of the study shed light on ancient human society and help to bridge the cultural chasm between humans and other species. The researchers say that to fully understand those elements that make us different from other animals, future work should focus on the mental abilities of individuals and not solely mechanisms of social learning.

Cognitive requirements of cumulative culture: teaching is useful but not essential by Elena Zwirner and Alex Thornton is published in Scientific Reports

Comments Off on Rice Basket Study Rethinks Roots Of Human Culture

Ancient Scroll Found in Holy Ark Read with Advanced Technology

June 23rd, 2016The Daily Journalist.

For the first time, advanced technologies made it possible to read parts of a scroll that is at least 1,500 years old, which was excavated in 1970 but at some point earlier had been badly burned.

The scroll was discovered inside the Holy Ark of the synagogue at Ein Gedi in Israel. High-resolution scanning and University of Kentucky Professor Brent Seales’ revolutionary virtual unwrapping tool revealed verses from the beginning of the Book of Leviticus suddenly coming back to life.

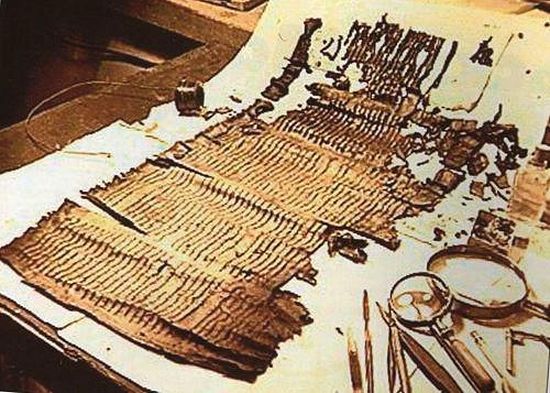

Unwrapped texture image of the Ein Gedi scroll, produced by Seales and his research team, showing letters of the Hebrew alphabet.

On Monday the rare find was presented at a press conference in Jerusalem, attended by Israel’s Minister of Culture and Sports, MK Miri Regev, and the director of the Israel Antiquities Authority, Israel Hasson. Seales attended via Skype.

“The text revealed today from the Ein Gedi scroll was possible only because of the collaboration of many different people and technologies,” said Seales, who is professor and chair of the UK College of Engineering’s Department of Computer Science. “The last step of virtual unwrapping, done at the University of Kentucky through the hard work of a team of talented students, is especially satisfying because it has produced readable, identifiable, biblical text from a scroll thought to be beyond rescue.”

(1)

The parchment scroll was unearthed in 1970 in archaeological excavations in the synagogue at Ein Gedi, headed by the late Dan Barag and Sefi Porath. However, due to its charred condition, it was not possible to either preserve or decipher it.

The Lunder Family Dead Sea Scrolls Conservation Center of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), which uses state of the art and advanced technologies to preserve and document the Dead Sea scrolls, enabled the discovery of this important find. It turns out that part of this scroll is from the beginning of the Book of Leviticus, written in Hebrew, and dated by C14 analysis, a form of radiometric dating used to determine the age of organic remains in ancient objects) to the late sixth century C.E. To date, this is the most ancient scroll from the five books of the Hebrew Bible to be found since the Dead Sea scrolls, most of which are ascribed to the end of the Second Temple period (first century B.C.E.-first century C.E.).

The Israel Antiquities Authority cooperated with scientists from Israel and abroad to preserve and digitize the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The Ein Gedi scroll was scanned with a micro-computed tomography machine from Skyscan (Bruker). Data from the scan is the sole basis of Seales’ software analysis. The scanning process is x-ray-based and completely non-invasive as the Ein Gedi scroll is badly damaged from fire and cannot be physically opened. The scans were done in Israel with assistance from Merkel Technologies Company, Ltd. Israel and Pnina Shor, curator and director of IAA’s Dead Sea Scrolls Projects, provided the data to Seales for analysis. Results were produced non-invasively from scan data alone – the Ein Gedi scroll itself remains intact and unopened.

“The partnership with Pnina Shor of the IAA has been particularly satisfying in the way she has enabled our team to work on data from one of the most storied and valuable collections in the world,” Seales said. “I am humbled by her trust in our research team, and gratified to produce for her and the entire scholarly community these exceptional results.”

The results come from research and a software prototype designed to do “virtual unwrapping” of surfaces from within volumetric scans. This unwrapping process allows the visualization of evidence of writing on a surface from within a scanned volume. Because the surfaces of the object being scanned are not flat like a book – rather they are rolled up as a scroll – the visualization of the surface and the evidence of writing upon the surface is a complex process.

(2)

“I have been using the word ‘surface’ to refer to the page of biblical text we have revealed. But this is a term of geometry, not of precise position,” Seales said. “The page actually comes from a layer buried deep within the many wraps of the scroll body, and is possible to view it only through the remarkable results of our software, which implements the research idea of ‘virtual unwrapping.'”

Thus, the great surprise and excitement when the first eight verses of the Book of Leviticus suddenly became legible:

“The Lord summoned Moses and spoke to him from the tent of meeting, saying: Speak to thepeople of Israel and say to them: When any of you bring an offering of livestock to the Lord, you shall bring your offering from the herd or from the flock. If the offering is a burnt-offering from the herd, you shall offer a male without blemish; you shall bring it to the entrance of the tent of meeting, for acceptance in your behalf before the Lord. You shall lay your hand on the head of the burnt-offering, and it shall be acceptable in your behalf as atonement for you. The bull shall be slaughtered before the Lord; and Aaron’s sons the priests shall offer the blood, dashing the blood against all sides of the altar that is at the entrance of the tent of meeting. The burnt-offering shall be flayed and cut up into its parts. The sons of the priest Aaron shall put fire on the altar and arrange wood on the fire. Aaron’s sons the priests shall arrange the parts, with the head and the suet, on the wood that is on the fire on the altar. (Leviticus 1:1-8).

This is the first time in any archaeological excavation that a Torah scroll was found in a synagogue, particularly inside a Holy Ark.

Comments Off on Ancient Scroll Found in Holy Ark Read with Advanced Technology

Researchers Find Highland East Asian Origin for Prehistoric Himalayan Populations

June 22nd, 2016

The Daily Journalist.

In a collaborative study by the University of Oklahoma, University of Chicago, University of California, Merced, and Uppsala University, researchers conduct the first ancient DNA investigation of the Himalayan arc, generating genomic data for eight individuals ranging in time from the earliest known human settlements to the establishment of the Tibetan Empire. The findings demonstrate that the genetic make-up of high-altitude Himalayan populations has remained remarkably stable despite cultural transitions and exposure to outside populations through trade.

Christina Warinner, senior author and professor in the Department of Anthropology, OU College of Arts and Sciences, and corresponding authors Anna Di Rienzo, Department of Human Genetics, University of Chicago, and Mark Aldenderfer, School of Social Sciences, Humanities and Arts, University of California, Merced, collaborated on the study published June 20, 2016 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciencesarticle, “Long-term genetic stability and a high altitude East Asian origin for the peoples of the high valleys of the Himalayan arc.”

Prehistoric Himalayan settlements are remote and only accessible today by horse and on foot.

“In this study, we demonstrate that the Himalayan mountain region was colonized by East Asians of high altitude origin, followed by millennia of genetic stability despite marked changes in material culture and mortuary behavior,” said Warinner.

Since prehistory, the Himalayan mountain range has presented a formidable barrier to population migration, while at the same time its transverse valleys have long served as conduits for trade and exchange. Yet, despite the economic and cultural importance of Himalayan trade routes, little was known about the region’s peopling and early population history. The high altitude transverse valleys of the Himalayan arc were among the last habitable places permanently colonized by prehistoric humans due to the challenges of resource scarcity, cold stress and hypoxia.

“Ancient DNA has the power to reveal aspects of population history that are very difficult to infer from modern populations or archaeological material culture alone,” said Aldenderfer.

The modern populations of these valleys, who share cultural and linguistic affinities with peoples found today on the Tibetan plateau, were commonly assumed to be the descendants of the earliest inhabitants of the Himalayan arc. However, this assumption had been challenged by archaeological and osteological evidence suggesting these valleys may have been originally populated from areas other than the Tibetan plateau, including those at low elevation.

To address the problem, Warinner and colleagues sequenced the nuclear and mitochondrial genomes of eight high-altitude Himalayan individuals dating to three distinct cultural periods spanning 3150 to 1250 years before present. The authors compared these ancient DNA sequences to genetic data from diverse modern humans, including four Sherpa and two Tibetans from Nepal.

All eight prehistoric individuals across the three time periods were most closely related to contemporary highland East Asian populations, i.e., the Sherpa and Tibetans, strengthening evidence that the diverse material culture of prehistoric Himalayan populations is the result of acculturation or culture diffusion rather than large-scale gene flow or population replacement from outside highland East Asia.

Even more revealing, both prehistoric individuals and contemporary Tibetan populations shared beneficial mutations in two genes, EGLN1 and EPAS1, which are implicated in adaptation to low-oxygen conditions found at high altitudes, but EGLN1 adaptations were observed earlier.

“For me, the most tantalizing finding in this study is that the temporal dynamics of the two main adaptive alleles appears to be quite different, suggesting a complex history of how humans adapted to this extreme environment. I am excited at the idea that ancient DNA may allow us to further dissect this history in the future,” said Di Rienzo.

The study broke new ground in other areas as well, yielding the first ancient whole genomes of East Asian ancestry and the highest coverage ancient human genome from Asia (7x coverage) sequenced to date.

“Although hundreds of ancient genomes have been reported for individuals of European and western Eurasian ancestry, this is the first study to recover ancient whole genomes of genetic East Asians,” said Choongwon Jeong, first author of the study, University of Chicago. “Continued investigations of ancient Asian populations will reveal how our ancestors adapted to the overwhelmingly diverse environments found in eastern Eurasia.”

Comments Off on Researchers Find Highland East Asian Origin for Prehistoric Himalayan Populations

Did the Khazars Convert To Judaism? New Research Says ‘No’

June 21st, 2016

The Daily Journalist.

Did the Khazars convert to Judaism? The view that some or all Khazars, a central Asian people, became Jews during the ninth or tenth century is widely accepted. But following an exhaustive analysis of the evidence, Hebrew University of Jerusalem researcher Prof. Shaul Stampfer has concluded that such a conversion, “while a splendid story,” never took place.

Prof. Shaul Stampfer is the Rabbi Edward Sandrow Professor of Soviet and East European Jewry, in the department of the History of the Jewish People at the Hebrew University’s Mandel Institute of Jewish Studies. The research has just been published in the Jewish Social Studies journal, Vol. 19, No. 3 (online at http://bit.ly/khazars).

From roughly the seventh to tenth centuries, the Khazars ruled an empire spanning the steppes between the Caspian and Black Seas. Not much is known about Khazar culture and society: they did not leave a literary heritage and the archaeological finds have been meager. The Khazar Empire was overrun by Svyatoslav of Kiev around the year 969, and little was heard from the Khazars after. Yet a widely held belief that the Khazars or their leaders at some point converted to Judaism persists.

Reports about the Jewishness of the Khazars first appeared in Muslim works in the late ninth century and in two Hebrew accounts in the tenth century. The story reached a wider audience when the Jewish thinker and poet Yehudah Halevi used it as a frame for his book The Kuzari. Little attention was given to the issue in subsequent centuries, but a key collection of Hebrew sources on the Khazars appeared in 1932 followed by a little-known six-volume history of the Khazars written by the Ukrainian scholar Ahatanhel Krymskyi.

Many studies have followed, and the story has also garnered considerable non-academic attention; for example, Shlomo Sand’s 2009 bestseller, The Invention of the Jewish People, advanced the thesis that the Khazars became Jews and much of East European Jewry was descended from the Khazars. But despite all the interest, there was no systematic critique of the evidence for the conversion claim other than a stimulating but very brief and limited paper by Moshe Gil of Tel Aviv University.

Stampfer notes that scholars who have contributed to the subject based their arguments on a limited corpus of textual and numismatic evidence. Physical evidence is lacking: archaeologists excavating in Khazar lands have found almost no artifacts or grave stones displaying distinctly Jewish symbols. He also reviews various key pieces of evidence that have been cited in relation to the conversion story, including historical and geographical accounts, as well as documentary evidence.

Among the key artifacts are an apparent exchange of letters between the Spanish Jewish leader Hasdai ibn Shaprut and Joseph, king of the Khazars; an apparent historical account of the Khazars, often called the Cambridge Document or the Schechter Document; various descriptions by historians writing in Arabic; and many others.

Taken together, Stampfer says, these sources offer a cacophony of distortions, contradictions, vested interests, and anomalies in some areas, and nothing but silence in others. A careful examination of the sources shows that some are falsely attributed to their alleged authors, and others are of questionable reliability and not convincing.

Many of the most reliable contemporary texts, such as the detailed report of Sallam the Interpreter, who was sent by Caliph al-Wathiq in 842 to search for the mythical Alexander’s wall; and a letter of the patriarch of Constantinople, Nicholas, written around 914 that mentions the Khazars, say nothing about their conversion.

Citing the lack of any reliable source for the conversion story, and the lack of credible explanations for sources that suggest otherwise or are inexplicably silent, Stampfer concludes that the simplest and most convincing answer is that the Khazar conversion is a legend with no factual basis. There never was a conversion of a Khazar king or of the Khazar elite, he says.

Years of research went into this paper, and Stampfer ruefully noted that “Most of my research until now has been to discover and clarify what happened in the past. I had no idea how difficult and challenging it would be to prove that something did not happen.”

In terms of its historical implications, Stampfer says the lack of a credible basis for the conversion story means that many pages of Jewish, Russian and Khazar history have to be rewritten. If there never was a conversion, issues such as Jewish influence on early Russia and ethnic contact must be reconsidered.

Stampfer describes the persistence of the Khazar conversion legend as a fascinating application of Thomas Kuhn’s thesis on scientific revolution to historical research. Kuhn points out the reluctance of researchers to abandon familiar paradigms even in the face of anomalies, instead coming up with explanations that, though contrived, do not require abandoning familiar thought structures. It is only when “too many” anomalies accumulate that it is possible to develop a totally different paradigm—such as a claim that the Khazar conversion never took place.

Stampfer concludes, “We must admit that sober studies by historians do not always make for great reading, and that the story of a Khazar king who became a pious and believing Jew was a splendid story.” However, in his opinion, “There are many reasons why it is useful and necessary to distinguish between fact and fiction – and this is one more such case.”

Comments Off on Did the Khazars Convert To Judaism? New Research Says ‘No’

TAU Discovers Extensive Fabric Collection Dating Back to Kings David and Solomon

June 20th, 2016

The Daily Journalist.

Textiles found at Timna Valley archaeological dig by Tel Aviv University researchers provide a colorful picture of a complex society during the time of Kings David and Solomon.

The ancient copper mines in Timna are located deep in Israel’s Arava Valley and are believed by some to be the site of King Solomon’s mines. The arid conditions of the mines have seen the remarkable preservation of 3,000-year-old organic materials, including seeds, leather and fabric, and other extremely rare artifacts that provide a unique window into the culture and practices of this period.

A Timna excavation team from Tel Aviv University led by Dr. Erez Ben-Yosef has uncovered an extensive fabric collection of diverse color, design and origin. This is the first discovery of textiles dating from the era of David and Solomon, and sheds new light on the historical fashions of the Holy Land. The textiles also offer insight into the complex society of the early Edomites, the semi-nomadic people believed to have operated the mines at Timna.

The tiny pieces of fabric, some only 5 x 5 centimeters in size, vary in color, weaving technique and ornamentation. “Some of these fabrics resemble textiles only known from the Roman era,” said Dr. Orit Shamir, a senior researcher at the Israel Antiquities Authority, who led the study of the fabrics themselves.

“No textiles have ever been found at excavation sites like Jerusalem, Megiddo and Hazor, so this provides a unique window into an entire aspect of life from which we’ve never had physical evidence before,” Dr. Ben-Yosef said. “We found fragments of textiles that originated from bags, clothing, tents, ropes and cords.

“The wide variety of fabrics also provides new and important information about the Edomites, who, according to the Bible, warred with the Kingdom of Israel. We found simply woven, elaborately decorated fabrics worn by the upper echelon of their stratified society. Luxury grade fabric adorned the highly skilled, highly respected craftsmen managing the copper furnaces. They were responsible for smelting the copper, which was a very complicated process.”

A trove of the “Seven Species”

The archaeologists also recently discovered thousands of seeds of the Biblical “Seven Species” at the site — the two grains and five fruits considered unique products of the Land of Israel. Some of the seeds were subjected to radiocarbon dating, providing robust confirmation for the age of the site.

“This is the first time seeds from this period have been found uncharred and in such large quantities,” said Dr. Ben-Yosef. “With the advancement of modern science, we now enjoy research options that were unthinkable a few decades ago. We can reconstruct wine typical of King David’s era, for example, and understand the cultivation and domestication processes that have been preserved in the DNA of the seed.”

The power of copper

Copper was used to produce tools and weapons and was the most valuable resource in ancient societies. Its production required many levels of expertise. Miners in ancient Timna may have been slaves or prisoners — theirs was a simple task performed under difficult conditions. But the act of smelting, of turning stone into metal, required an enormous amount of skill and organization. The smelter had to manage some 30 to 40 variables in order to produce the coveted copper ingots.

“The possession of copper was a source of great power, much as oil is today,” Dr. Ben-Yosef said. “If a person had the exceptional knowledge to ‘create copper,’ he was considered well-versed in an extremely sophisticated technology. He would have been considered magical or supernatural, and his social status would have reflected this.”

To support this “silicon valley” of copper production in the middle of the desert, food, water and textiles had to be transported long distances through the unforgiving desert climate and into the valley. The latest discovery of fabrics, many of which were made far from Timna in specialized textile workshops, provides a glimpse into the trade practices and regional economy of the day.

“We found linen, which was not produced locally. It was most likely from the Jordan Valley or Northern Israel. The majority of the fabrics were made of sheep’s wool, a cloth that is seldom found in this ancient period,” said TAU masters student Vanessa Workman. “This tells us how developed and sophisticated both their textile craft and trade networks must have been.”

(1)

“‘Nomad’ does not mean ‘simple,'” said Dr. Ben-Yosef. “This discovery strengthens our understanding of the Edomites as an important geopolitical presence. The fabrics are of a very high quality, with complex designs and beautiful dyes.”

Comments Off on TAU Discovers Extensive Fabric Collection Dating Back to Kings David and Solomon

World’s Oldest Weather Report Found, Could Revise Bronze Age Chronology

June 18th, 2016Generally, weather reports have played an essential role in all civilizations for many years. From farmers needing to know the weather for their crops to merchants wanting to know the right weather conditions before starting their voyages, these forecasts are a vital part of history. However, before the advent of modern tools used to predict the weather, ancient people made use of signs of nature, including religious faith and old mythological proverbs for the forecasts.

That said, finding the world’s oldest weather report has become controversial as it could potentially revise Bronze Age chronology. Basically, an inscription on a 3,500-year-old stone block from Egypt may be one of the world’s oldest weather reports—and could provide new evidence about the chronology of events in the ancient Middle East.

A new translation of a 40-line inscription on the 6-foot-tall calcite block called the Tempest Stela describes rain, darkness and “the sky being in storm without cessation, louder than the cries of the masses.”

A new translation of a 6-foot-tall calcite block called the Tempest Stela suggests the Egyptian pharaoh Ahmose ruled at a time 30 to 50 years earlier than previously thought—a finding that could change scholars’ understanding of a critical juncture in the Bronze Age.

Two scholars at the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute believe the unusual weather patterns described on the slab were the result of a massive volcano explosion at Thera—the present-day island of Santorini in the Mediterranean Sea. Because volcano eruptions can have a widespread impact on weather, the Thera explosion likely would have caused significant disruptions in Egypt.

The new translation suggests the Egyptian pharaoh Ahmose ruled at a time closer to the Thera eruption than previously thought—a finding that could change scholars’ understanding of a critical juncture in human history as Bronze Age empires realigned. The research from the Oriental Institute’s Nadine Moeller and Robert Ritner appears in the spring issue of the Journal of Near Eastern Studies.

The Tempest Stela dates back to the reign of the pharaoh Ahmose, the first pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty. His rule marked the beginning of the New Kingdom, a time when Egypt’s power reached its height. The block was found in pieces in Thebes, modern Luxor, where Ahmose ruled.

If the stela does describe the aftermath of the Thera catastrophe, the correct dating of the stela itself and Ahmose’s reign, currently thought to be about 1550 B.C., could actually be 30 to 50 years earlier.

“This is important to scholars of the ancient Near East and eastern Mediterranean, generally because the chronology that archaeologists use is based on the lists of Egyptian pharaohs, and this new information could adjust those dates,” said Moeller, assistant professor of Egyptian archaeology at the Oriental Institute, who specializes in research on ancient urbanism and chronology.

In 2006, radiocarbon testing of an olive tree buried under volcanic residue placed the date of the Thera eruption at 1621-1605 B.C. Until now, the archeological evidence for the date of the Thera eruption seemed at odds with the radiocarbon dating, explained Oriental Institute postdoctoral scholar Felix Hoeflmayer, who has studied the chronological implications related to the eruption. However, if the date of Ahmose’s reign is earlier than previously believed, the resulting shift in chronology “might solve the whole problem,” Hoeflmayer said.

The revised dating of Ahmose’s reign could mean the dates of other events in the ancient Near East fit together more logically, scholars said. For example, it realigns the dates of important events such as the fall of the power of the Canaanites and the collapse of the Babylonian Empire, said David Schloen, associate professor in the Oriental Institute and Near Eastern Languages & Civilizations on ancient cultures in the Middle East.

(1)

“This new information would provide a better understanding of the role of the environment in the development and destruction of empires in the ancient Middle East,” he said.

For example, the new chronology helps to explain how Ahmose rose to power and supplanted the Canaanite rulers of Egypt—the Hyksos—according to Schloen. The Thera eruption and resulting tsunami would have destroyed the Hyksos’ ports and significantly weakened their sea power.

In addition, the disruption to trade and agriculture caused by the eruption would have undermined the power of the Babylonian Empire and could explain why the Babylonians were unable to fend off an invasion of the Hittites, another ancient culture that flourished in what is now Turkey.

Given these circumstances, knowing the oldest civilizations in the world can be a crucial part of understanding the history of human settlements on earth, their different cultures, and their contributions to the present condition of the world. In this case, it involves understanding the oldest weather report to get a more accurate representation of time and the arrangement of events according to their occurrences.

‘A TEMPEST OF RAIN’

On the other hand, part of understanding the relationship between the world’s oldest weather report and the possible revision of the Bronze Age chronology is familiarizing the concept of ‘tempest of rain.’ Historically, some researchers consider the text on the Tempest Stela to be a metaphorical document that described the impact of the Hyksos invasion. However, Ritner’s translation shows that the text was more likely a description of weather events consistent with the disruption caused by the massive Thera explosion.

Ritner said the text reports that Ahmose witnessed the disaster—the description of events in the stela text is frightening.

The stela’s text describes the “sky being in storm” with “a tempest of rain” for a period of days. The passages also describe bodies floating down the Nile like “skiffs of papyrus.”

Importantly, the text refers to events affecting both the delta region and the area of Egypt further south along the Nile. “This was clearly a major storm, and different from the kinds of heavy rains that Egypt periodically receives,” Ritner said.

In addition to the Tempest Stela, a text known as the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus from the reign of Ahmose also makes a special point of mentioning thunder and rain, “which is further proof that the scholars under Ahmose paid close and particular attention to matters of weather,” Ritner said.

Marina Baldi, a scientist in climatology and meteorology at the Institute of Biometeorology of the National Research Council in Italy, has analyzed the information on the stela along with her colleagues and compared it to known weather patterns in Egypt.

A dominant weather pattern in the area is a system called “the Red Sea Trough,” which brings hot, dry air to the area from East Africa. When disrupted, that system can bring severe weather, heavy precipitation and flash flooding, similar to what is reported on the Tempest Stela.

(2)

“A modification in the atmospheric circulation after the eruption could have driven a change in the precipitation regime of the region. Therefore the episode in the Tempest Stela could be a consequence of these climatological changes,” Baldi explained.

Other work is underway to get a clearer idea of accurate dating around the time of Ahmose, who ruled after the Second Intermediate period when the Hyksos people seized power in Egypt. That work also has pushed back the dates of his reign closer to the explosion on Thera, Moeller explained. But with the discovery of the world’s oldest weather report, revising the Bronze Age chronology could be possible. Although other pieces of evidence may be needed to materialize the revision, the discovery proves that there are still more things to know and understand about ancient civilizations in the world, their history, and their culture.

Comments Off on World’s Oldest Weather Report Found, Could Revise Bronze Age Chronology

The Battle of Waterloo: Why Does It Matter?

June 17th, 2016

The Daily Journalist.

Professor Charles Esdaile, from the University of Liverpool Department of History, is the author of numerous works on the Napoleonic period including `Napoleon’s Wars: An International History.’

18 June – was the 200th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo.

Over in Belgium at least 100,000 people were present at the ceremonies and re-enactments held on the battlefield.

So why all the fuss? Why should we remember a day of horror marked by the most terrible extremes of human misery? To answer this, let me begin with a little history.

Napoleon Bonaparte

Defeated by a massive international coalition in 1814, Napoleon Bonaparte was sent into exile in Elba, but at the end of February 1815 he escaped and sailed to the south of France.

To use a Spanish analogy, he immediately ‘pronounced’ against the regime of the restored Louis XVIII whereupon the much disaffected army rallied en masse to his cause.

By 20 March Napoleon was back in Paris, and Louis in exile in Ghent, but the emperor was anything but secure: on the contrary, he was immediately declared an outlaw by the powers of Europe.

The Battle of Waterloo

Threatened with invasion from all sides, Napoleon struck at his nearest opponents – the Anglo-Dutch army of the Duke of Wellington and the Prussian army of Marshal Blucher – in the hope that a dramatic victory would cause his opponents to make peace, and the result was a four-day campaign that culminated in the complete defeat of the French at Waterloo. The emperor then abdicated, surrendered to the British and was sent off to exile in Saint Helena.

Why does it matter?

So much for the history, but why does it matter? The answer, quite simply, is that, to paraphrase Wellington, the only thing sadder than a battle won would have been a battle lost.

Engaging in counter-factual history is a dangerous business, but if there is one thing that we can be pretty certain of is that even had Napoleon had been victorious in the Waterloo campaign, he would simply have been defeated further down the line: he faced massive domestic opposition, was outnumbered by at least 3:1 and was well past his mental and physical best.

On top of this, there was no chance of significant popular support from elsewhere in Europe – by 1814 French rule was widely hated – while the coalition against Napoleon was rock solid. In short, all that would have happened had Napoleon won would have been that there would have been a lot more killing, a lot more misery and a lot more destruction and all for precisely the same result.

Human cost

Exactly what this would have meant in human terms is best dealt with by comparison with the first day of the Somme. On 1 July 1916, 70,000 men were killed or wounded in an area some 60 miles long by 20 miles wide, but on 18 June 1815 some 45,000 men were killed or wounded in an area 6 miles square. The battlefield, then, was a scene of absolute horror and one that thank God did not have to be repeated.

The reaction Waterloo provoked was so strong that it led to the first attempt in the history of the world to resolve disputes by the establishment of a structure for conciliation and negotiation (i.e. the Congress System), this alone is worth remembering it for.

Napoleonic Legend

However, at the same time, the bicentenary is also a useful moment for reflecting on the Napoleonic legend. To this day there are many people who see the emperor as an apostle of liberty, and, still worse, as witnessed by current programmes on BBC2 and Radio 4, there are still those who seek to defend such ideas.

In reality, however, Napoleon was nothing than a warlord who sought to create a colonial empire in the heart of Europe, and his downfall is therefore truly a moment to savour.”

Comments Off on The Battle of Waterloo: Why Does It Matter?

Gath: Biblical Philistine City of Goliath Found by Archaeologists

June 16th, 2016

The Daily Journalist.

The Ackerman Family Bar-Ilan University Expedition to Gath, headed by Prof. Aren Maeir, has discovered the fortifications and entrance gate of the biblical city of Gath of the Philistines, home of Goliath and the largest city in the land during the 10th-9th century BCE, about the time of the “United Kingdom” of Israel and King Ahab of Israel. The excavations are being conducted in the Tel Zafit National Park, located in the Judean Foothills, about halfway between Jerusalem and Ashkelon in central Israel.

This is a view of the remains of the Iron Age city wall of Philistine Gath.

Prof. Maeir, of the Martin (Szusz) Department of Land of Israel Studies and Archaeology, said that the city gate is among the largest ever found in Israel and is evidence of the status and influence of the city of Gath during this period. In addition to the monumental gate, an impressive fortification wall was discovered, as well as various building in its vicinity, such as a temple and an iron production facility. These features, and the city itself were destroyed by Hazael King of Aram Damascus, who besieged and destroyed the site at around 830 BCE.

The city gate of Philistine Gath is referred to in the Bible (in I Samuel 21) in the story of David’s escape from King Saul to Achish, King of Gath.

Now in its 20th year, the Ackerman Family Bar-Ilan University Expedition to Gath, is a long-term investigation aimed at studying the archaeology and history of one of the most important sites in Israel. Tell es-Safi/Gath is one of the largest tells (ancient ruin mounds) in Israel and was settled almost continuously from the 5th millennium BCE until modern times.

These are views of the Iron Age fortifications of the lower city of Philistine Gath.

The archaeological dig is led by Prof. Maeir, along with groups from the University of Melbourne, University of Manitoba, Brigham Young University, Yeshiva University, University of Kansas, Grand Valley State University of Michigan, several Korean universities and additional institutions throughout the world.

Among the most significant findings to date at the site: Philistine Temples dating to the 11th through 9th century BCE, evidence of an earthquake in the 8th century BCE possibly connected to the earthquake mentioned in the Book of Amos I:1, the earliest decipherable Philistine inscription ever to be discovered, which contains two names similar to the name Goliath; a large assortment of objects of various types linked to Philistine culture; remains relating to the earliest siege system in the world, constructed by Hazael, King of Aram Damascus around 830 BCE, along with extensive evidence of the subsequent capture and destruction of the city by Hazael, as mentioned in Second Kings 12:18; evidence of the first Philistine settlement in Canaan (around 1200 BCE); different levels of the earlier Canaanite city of Gath; and remains of the Crusader castle “Blanche Garde” at which Richard the Lion-Hearted is known to have been

Comments Off on Gath: Biblical Philistine City of Goliath Found by Archaeologists

An American Pompeii: Mayan Village Preserved in Volcanic Ash for 1400 Years

June 15th, 2016The Daily Journalist.

A continuing look at a Maya village in El Salvador–frozen in time by a blanket of volcanic ash from 1,400 years ago–shows the farming families who lived there went about their daily lives with virtually no strong-arming by the elite royalty lording over the valley.

Instead, archaeological evidence indicates significant interactions at the village of Ceren took place among families, village elders, craftspeople and specialty maintenance workers. This research comes from a new University of Colorado Boulder (CU-Boulder) study, funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF).

Ceren is the best-preserved ancient Maya village in all of Latin America. In A.D. 660, the village was blasted by toxic gas, pummeled by lava bombs and then choked by a 17-foot layer of ash falling over several days after the Loma Caldera volcano, less than half a mile away, erupted.

Structures at Ceren were buried in up to 17 feet of ash over a period of several days, freezing the 1,400-year-old village in time.

Discovered in 1978 by CU-Boulder anthropology Professor Payson Sheets, Ceren has been called the “New World Pompeii.” The degree of preservation is so great researchers can see marks of finger swipes in ceramic bowls, and human footprints in gardens that host ghostly ash casts of corn stalks. Researchers have also uncovered thatched roofs, woven blankets and bean-filled pots.

Some Maya archaeological records document “top-down” societies, where the elite class made most political and economic decisions, at times exacting tribute or labor from villages, said Sheets. But at Ceren, the villagers appear to have had free reign regarding their architecture, crop choices, religious activities and economics.

“This is the first clear window anyone has had on the daily activities and the quality of life of Maya commoners back then,” said Sheets, who is directing the excavation. “At Ceren we found virtually no influence and certainly no control by the elites.”

This is a view of the Ceren sacbe buried under about 16 feet of ash. The trench on the left side was a drainage canal to catch excess rainwater.

A paper on the subject appears in the current issue of Latin American Antiquity published by the Society for American Archaeology. The 10-acre Ceren research area was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1993.

Ceren is believed to have been home to about 200 people. Researchers have excavated 12 buildings, including living quarters, storehouses, workshops, kitchens, religious buildings and a community sauna. There are dozens of unexcavated structures, and perhaps even another settlement or two under the Loma Caldera volcanic ash, which covers an area of roughly two square miles, Sheets said. Thus far, no bodies have been found, an indication a precursor earthquake may have given residents a running start just before the eruption.

The only relationship Ceren commoners had with Maya elite was indirect, through public marketplace transactions in El Salvador’s Zapotitan Valley. There, Ceren farmers likely swapped surplus crops or crafts for coveted specialty items like jade axes, obsidian knives and colorfully decorated polychrome pots, all of which elites arranged to have brought to market from a distance. Virtually every Ceren household had a jade axe–which is harder than steel–used for tree cutting, building and woodworking.

“The Ceren people could have chosen to do business at about a dozen different marketplaces in the region,” said Sheets. “If they thought the elites were charging too much at one marketplace, they were free to vote with their feet and go to another.”

Professor Payson Sheets points to the imprint of several toes from a footprint left on the Ceren sacbe. Footprints pointed away from village and may have been made by Mayans fleeing the volcanic eruption.

One of the excavated community buildings has two large benches in the front room, which Sheets believes were used by village elders when making decisions. One decision would have involved organizing the annual crop harvest festival, a celebratory eating and drinking ritual that appears to have been underway at Ceren when the Loma Caldera volcano abruptly blew just north of the village, said Sheets.

He believes the villagers fled south, perhaps along a white road leading away from the village discovered under 15 feet of ash in 2011. The elevated road, known as a sacbe (SOCK-bay), is about 2 meters wide and made from white tightly packed volcanic ash, with drainage ditches along each edge. The sacbe appears to split in the village and lead toward the plaza and two religious structures: the large ceremonial building and a second, smaller structure used by a female shaman.

Unique research