20,000 years ago, massive ice sheets cover a quarter of the globe. Populations of big game hunters live in small, mobile communities like in this reenactment, and gigantic mammoths roam the landscape. Suddenly and without warning, temperatures rise and the world starts to change. Much of the world we know today is formed as our planet and its life forms adapt to the abrupt change in climate.

Credit: channel.nationalgeographic.com/

New research from the University of Reading shows that Ice Age people living in Europe 15,000 years ago might have used forms of some common words including I, you, we, man and bark, that in some cases could still be recognized today.

Credit: Manhattan Museum of Natural History

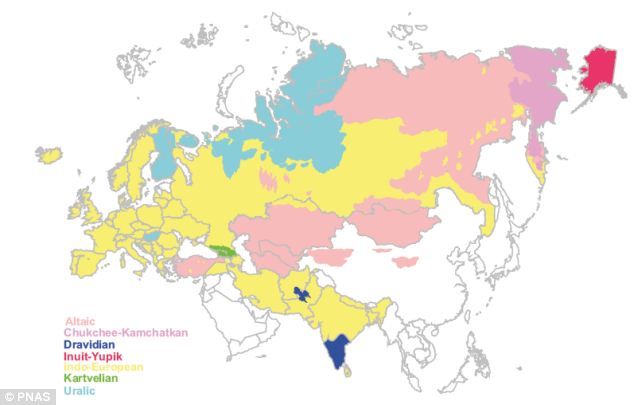

Using statistical models, Professor of Evolutionary Biology Mark Pagel and his team predicted that certain words would have changed so slowly over long periods of time as to retain traces of their ancestry for up to ten thousand or more years. These words point to the existence of a linguistic super-family tree that unites seven major language families of Eurasia¹.

Map showing approximate regions where languages from the seven Eurasiatic language families

are spoken. The color-shaded areas should be treated as suggestive only, as current language ranges will not necessarily correspond to original homelands, and language boundaries will often overlap. For example, the Indo-European language Swedish is spoken along with the Uralic Finnish in southern Finland

PNAS(map source: refs. 10, 16 and 34) (SI Text).

Previously linguists have relied solely on studying shared sounds among words to identify those that are likely to be derived from common ancestral words, such as the Latin pater and the English father. A difficulty with this approach is that two words might have similar sounds just by accident, such as the words team and cream.

To combat this problem, Professor Pagel’s team showed that a subset of words used frequently in everyday speech, are more likely to be retained over long periods of time. The team used this method to predict words likely to have shared sounds, giving greater confidence that when such sound similarities are discovered they do not merely reflect the workings of chance.

Twenty-three words with cognate class sizes of four or more among the Eurasiatic language families

*Defined as the number (of seven) of Eurasiatic language families that are reconstructed as cognate for the word used to convey the meaning shown.

† The rate of lexical replacement measured in number of expected new or unrelated words per 1,000 y and rates of replacement expressed as “halflives” or the expected time until a word has a 50% chance of being replaced by a new noncognate word (14).

‡ The frequency of use per million based on mean of 17 languages from six language families and the two isolates (16).

Credit: Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences

Professor Pagel, from the University of Reading’s School of Biological Sciences, said: “The way in which we use a certain set of words in everyday speech is something common to all human languages. We discovered numerals, pronouns and special adverbs are replaced far more slowly, with linguistic half-lives of once every 10,000 or even more years. As a rule of thumb, words used more than about once per thousand in everyday speech were seven to ten times more likely to show deep ancestry in the Eurasian super-family.”

Professor Pagel’s previous research on the evolution of human languages has built up a picture of how our 7,000 living human languages have evolved. Professor Pagel and his research team have documented the shared patterns in the way we use language and researched why some words succeed and others have become obsolete over time. This is done by using statistical estimates of rates of lexical replacement for a range of vocabulary items in the Indo-European languages. The variation in replacement rates makes the most common vocabulary items in these languages promising candidates for estimating the divergence between pairs of languages.