The Daily Journalist.

EU researchers say we could be doing so much more with our windows. We could use them to collect solar energy? EU-funded researchers are developing an innovative solution to do just that. Their concept is based on thin layers of running water in the glazing, which is also designed to help maintain comfortable indoor temperatures and block out excess sunlight.

.

The Fluidglass project is developing windows that might one day leave standard glazing in the shade: in addition to providing insulation and keeping out the glare of overly bright days, they can be used as heating or cooling panels and harvest solar energy.

Credit: © Jürgen Fälchle – fotolia.com

Glazing today usually involves two or three panes of glass. These panes don’t quite touch, but instead are spaced to leave room for thin layers of gas or an enclosed vacuum, which act as insulation. “Our glass is a combination of this standard glazing with additional, fluid-filled layers – one on the outside of the window, and one on the inside,” says Fluidglass coordinator Anne-Sophie Zapf of the University of Liechtenstein’s Institute of Architecture and Planning.

Crystal-clear collectors

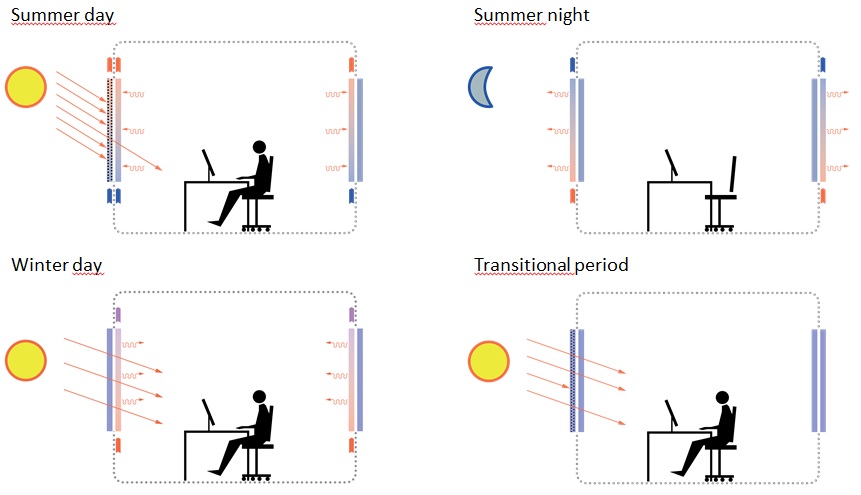

The fluid in these additional layers is essentially water, she explains. The outer layer deals with the rays; it is enriched with nanoparticles that soak up solar energy and filter the light. The inner layer, which can be warm or cold depending on the needs, provides heating or cooling as required to keep room temperatures pleasant.

The water composing these two layers is fed through in a continuous stream. The composition and temperature of the fluid can therefore be adapted as necessary to adjust to varying conditions.

The innovative functionalities of the outer layer rely on nanoparticles that absorb solar energy and warm up the water in the outer layer, Zapf notes. This hot water is then piped towards a storage tank, a heat exchanger or a heat pump. The energy extracted from it can, for example, be used to power the building’s heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system.

Replacing four different systems by one, FLUIDGLASS brings a significant cost advantage compared to existing solutions. FLUIDGLASS increases the thermal performance of the whole building resulting in energy savings potential of 50%-70% for retrofitting and 20%-30% for new low energy buildings while the comfort for the user is significantly improved at the same time. Compared to state-of-the-art solar collectors FLUIDGLASS has the elegant but neutral aesthetics of clear glass. This allows full design freedom for the architect in new built applications and enables retrofits that do not destroy the original look of an existing building.

The number of particles in the fluid varies, and so does the amount of light that the windows let in: in addition to collecting energy, the particles, which are dark, act as tiny parasols. Injecting them into the liquid produces a tint and provides shade.

The intensity of the tint and the corresponding level of shade can be tuned flexibly by adding or removing particles. “The more there are in the fluid, the darker it gets, and the more energy it can collect,” says Zapf.

Glazing in a new light

With Fluidglass glazing, what at first sight seems like a humble window might thus turn out to be a transparent solar thermal collector. The various components inside — more particularly, the water and the separators between the various layers — are barely visible, says Zapf.

This feature means that the new collectors, once they are available to architects, could be integrated into façade designs in much the same way as standard glazing, Zapf notes. In existing constructions, the panels could be fitted without major alterations to the building envelope, she adds, and it would therefore be possible to upgrade properties without disfiguring them.

According to project estimates, the thermal performance of buildings equipped with Fluidglass technology would be considerably improved. Potential energy savings of 50 to 70% have been projected for retrofits. For new constructions already designed to use less energy, the team’s calculations indicate that choosing its innovation instead of standard glazing could reduce consumption by up to 30%.

Fluidglass builds on research first initiated in 1998, says Zapf. By the time the project ends in August 2017, the team hopes to have developed the concept into a marketable product, she notes, but there is still a lot to do in the remaining 17 months.

At the moment, the researchers are putting the final touches to a demonstrator — a shipping container converted into a room with a Fluidglass window — that will enable them to test their innovation in various climates. A summer in Cyprus will place very different demands on the proposed technology than the average winter in Liechtenstein, and the Fluidglass team wants to make sure that its windows will shine whatever the weather.