By Josep Colomer.

The first weeks of government in Greece of Syriza, the “radical left coalition”, shows that in the current European Union it’s extremely difficult to blatantly oppose the Brussels and Frankfurt consensus. New radical left parties have tried to be launched in Southern Europe in political contexts defined by the social-democracy’s adoption of mainstream economic policy and the communists’ lack of credibility as an alternative. However, the political space outside and between these two political traditions is very narrow.

The crucial reference for comparison is Germany. The German Social-democratic Party (SPD) was pioneer in dropping Marxism, hostility to capitalism and nationalizations and in accepting membership to NATO, as early as in 1959. A few years later, the SPD, led by Willy Brandt and Helmut Schmidt, entered the first of what would be several grand coalition governments with the Christian-democrats. Communism was not a feasible option in West Germany, as it was identified with the Soviet occupation of East Germany. The emergence of a new left alternative took one more generation. Initially, the Greens adopted rather radical leftist positions in economic and foreign policy. But the Greens were unequivocally anti-Communists, up to the point of merging with the Eastern anti-Communist opposition in a permanent join candidacy after the reunification of the country. Over time, the Greens strongly reinforced their pro-European Union stance and became a regular party able to enter government in coalition with the Social-democrats.

The situation has been different in Southern Europe. There were still nationalizations of private companies for ideological motives in France at the beginning of the presidency of Socialist Francois Mitterrand, who formed a coalition government with the Communists in 1981. It took barely a year, however, for the French Socialist party to abandon such a pathway. Very soon thereafter, the Socialists initiated the first of several “cohabitations” with the Conservatives. In his second term, Mitterrand appointed Prime Minister Michel Rocard –who was derided as an advocate of “the American left”— to chair a coalition cabinet with the Centrists. The attempts to set up a radical left alternative, which were strongly influenced by the legacy of Marxism and Communism, did not succeed in forming a viable governmental option. History repeats itself. After less than two years in government, the current Socialist president Francois Hollande appointed a new prime minister, Manuel Valls –a Rocard’s disciple–, who is adopting mainstream economic policies as designed by the European Union. No clear alternative is emerging outside.

In Italy, the Socialists led by Bettino Craxi chaired a coalition government with the Christian-democrats in the 1980s. The main leftist party, the Communists, also abandoned Marxism and evolved into vague progressive positions until it merged with former Socialists and Christian-democrats in the new Democratic Party. As President of the Republic, former Communist Giorgio Napolitano appointed two cabinets of independent experts until a broad coalition of center-left and center-right parties was formed. The length and gradualism of the process of change and dissolution of the previous Communist and Socialist parties made the formation of a consistent radical left alternative extremely difficult.

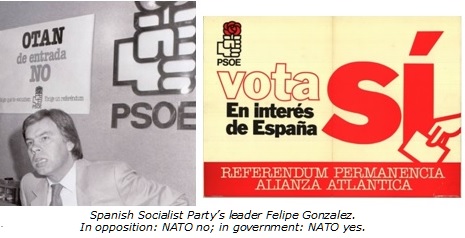

The Spanish Socialist party (PSOE) learned the lesson very soon. After losing the first two democratic elections in Spain in the late 1970s, the PSOE’s leader Felipe Gonzalez forced the party to abandon its allegiance to Marxism and to adopt pro-market economic policy commitments. The party won the following election in 1982, when the French leftist experiment had already been revised and, in this light, it didn’t even try to implement nationalizations or similar decisions. Soon thereafter the PSOE explicitly embraced NATO membership. For many years, the left radical alternative was held by the barely disguised Communist candidacy called United Left, which never became a real government option. Only after a new, recent period of Socialist governments in which the instructions from the EU became actual policy, a new left radical alternative has appeared. Under the name We Can (Podemos), it looks like a breath of fresh air, although its members are again re-disguised Communists. They are likely to be less successful in the coming general election than certain survey polls venture.

The recent and current attempts at building political alternatives to the left of the social-democrats greatly derive from changes at European level. But facing the standard postulates of market-economy and transatlantic foreign policy requires today the adoption of anti-European Union and nationalist positions, which implies even more insurmountable challenges than in the 1980s. In this context, the experience of Syriza in government in Greece might lead to either a big turnaround of its campaign slogans –something like what the German Greens, the French, the Spanish and the Italian Socialists and the Italian Communists did in their times– or to a quick governmental and electoral failure, as has happened to all far left alternatives that have been tried. In a year or two the dies of the new radical left in Southern Europe will be cast again.