September 28th, 2015

By Jeong Lee.

Introduction

This paper examines the conduct of the Afghanistan War under the Barack Obama administration and offers policy recommendations for the president.

Given the accelerated counterinsurgency warfare being waged by the weak Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) against the Taliban, a complete U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan would be imprudent. First, doing so could undermine U.S. credibility in the Middle East and South Asia because, as a great power, the United States cannot afford to lose wars. Second, a complete withdrawal is ill-advised in light of the fact that the strategic calculus in the Middle East still remains fraught with uncertainties.

For these reasons, the United States should take a minimalist but effective approach in an effort to contain the spread of jihad in Afghanistan if it hopes to retain its influence in the Middle East.

Background: Obama’s War in Afghanistan From 2011 to the Present

In 2009, President Barack Obama expanded the scope of the war in Afghanistan, thereby, increasing the troop presence by 30,000 ground troops. In addition, the president shifted his emphasis away from defeating to degrading the Taliban.

When Obama initially acceded to General McChrystal’s request for expanded efforts that require “a discrete ‘jump’ [in resources] to gain the initiative” in counterinsurgency (COIN) warfare, after 2011, he shifted his emphasis away from a costly COIN campaign to the selective targeting of his adversaries using Special Operations Forces (SOFs) and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs).

Indeed, when the president approved General McChrystal’s request for increased troop levels, he told the general that he had only one opportunity to get the strategy right.

Thus, when President Obama withdrew all U.S. combat troops from Afghanistan by the end of 2014, both the opponents of COIN and its proponents failed to understand that Obama’s initial emphasis on counterinsurgency did not necessarily mean that “Afghanistan now displaced all other issues atop the U.S. national security agenda” as Boston University historian Andrew Bacevich argued in his 2010 book,Washington Rules. There were several factors that accounted for the shift in Obama’s strategy from 2011 and 2014.

First, as General Bolger and the Boston University historian Andrew Bacevich both have argued, COIN turned out to be a costly endeavor that consumed time, U.S. resources, and U.S. lives.

Second, the transition from counterinsurgency to selective targeting seemed to offer a range of available options to the president, including, and if necessary, complete departure from Afghanistan.

Third, one immediate result of the Afghan surge had been the severe degradation, if not depletion, of both the Taliban and Al Qaida fighters. Fourth, as General Bolger suggests, one of the main reasons for the shift in Obama’s approach was that the U.S. was unable to obtain a full cooperation from Pakistan to operate within its territory.

Although the United States withdrew its combat units from Afghanistan in December, 2014, both President Obama and the newly-elected Afghan president, Mohammad Ashraf Ghani, signed a bilateral agreement “to keep in place our close security cooperation” in March this year .

According to the bilateral agreement, the U.S. would continue to “train, advise and assist” the ANSF—including the police force—as well as continue to embark upon counterterrorism (CT) missions meant to target Taliban and ISIL/DAESH fighters.

As if to confirm the continued U.S. military presence, the New York Times reported that the remaining U.S. troops in Afghanistan were engaged in “more aggressive range of military operations against the Taliban in recent months [than they had previously].”

Furthermore, the increased attacks against the Afghan police by the Taliban in an effort to undermine the legitimacy of the Afghan government in power have resulted in a tough fighting season this year as the U.S.-led coalition presence diminished from 80,000 troops to approximately about 9,800 U.S. and 13,000 to 14,000 NATO troops on the ground.

Another reason for the mounting casualties this year, according to General John F. Campbell, the current commander of the Resolute Support Mission and the United States Forces, Afghanistan, was the diminished CAS (close air support) from the U.S.-led NATO forces.

Policy Recommendations for the President: Adopt An Effective but Minimalist Approach to Contain Jihad in Afghanistan

In this section, I will attempt to offer policy recommendations that address the following questions. First, how do we define U.S. interests in Afghanistan? Secondly, in light of the current conflict with ISIL/DAESH, what are the options available for the United States to counter threats emanating from jihadists in the Af-Pak region? As the Afghanistan Study Group noted in their policy memo, one “vital” strategic objective in Afghanistan is to prevent Afghanistan from becoming a “safe haven” for the jihadist movement including the Taliban and ISIL/DAESH.

As such, the best option available for dealing with the jihadist movement in Afghanistan is the minimalist approach that is grounded in flexibility and pragmatism. To that end, the Obama administration should consider the following six options.

Maintain Minimal Troop Presence in the Af-Pak Region

With the gradual spread of ISIL/DAESH into the Af-Pak region, a complete withdrawal of U.S. military presence is no longer feasible because doing so could undermine U.S. credibility in the Middle East and in Central Asia. Secondly, the proliferation of ISIL/DAESH has shown that we can never predict how strategic calculus may change or evolve in the Greater Middle East.

As was confirmed by General Campbell during a Brookings panel discussion on Afghanistan earlier in August of this year, in light of the spread of ISIL/DAESH into Afghanistan, the sporadic combat engagements between the residual U.S. military personnel and the jihadists, along with the bilateral agreement between the U.S. and Afghanistan, may mean the U.S. will likely retain its presence in the Af-Pak region.

Indeed, both feature articles from the New York Times and PBS Frontline agree that although the Obama administration remains optimistic over the election of President Ghani, Ghani’s grip on his own country still remains tenuous.

It is also worth remembering that even though the Obama administration still maintains troop presence in Afghanistan for training, advising and assisting ANSF, according to Michael O’Hanlon, the Co-Director at the Brookings Institution’s Center for 21st Century Security and Intelligence, it is now seeking to transition into smaller “embassy training-type” missions by 2016 “although these missions remain subject to reconsideration.”

Although it is too early to predict what the future holds, these trends, in some sense, seem to validate counterinsurgency theorists’ arguments that COIN waged by the Afghan government forces remains as relevant within the context of the Afghanistan War.

|

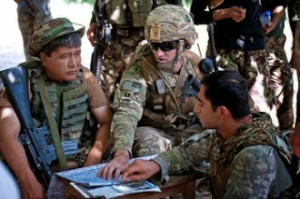

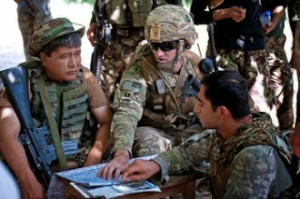

| Afghan national police and U.S. soldiers on a joint patrol in a neighborhood on the outskirts of Kandahar city. The U.S. strategy in Afghanistan depends on training and equipping the Afghan security forces, making them self-reliant and allowing U.S. troops to withdraw. (NPR) |

Thus, the Obama administration may have made the right choice to sign the March bilateral agreement with Ghani in an attempt to bolster the ANSF even as the U.S. military continues to embark upon counter-terrorism (CT) missions meant to go after and extirpate terrorist threats.

Work With President Ghani, But Only On Terms Favorable to the U.S. Interests

According to the New York Times article by Mark Mazetti and Eric Schmitt last November, the newly-elected President Ghani has developed a close rapport with General John Campbell, the U.S. commander in Afghanistan, and has reached out to the international community to foster legitimacy for his own government.[xviii] Indeed, Mazzetti and Schmitt quote General Campbell’s email as saying that the difference between his predecessor, Hamid Karzai, and Ghani “is night and day.”

Although one can construe these developments as encouraging signs, there are already concerns that Ghani is becoming increasingly dependent upon General Campbell’s assistance and counsel, and that his grip on his nation remains tenuous at best.

The last two indicators may not bode well for U.S. strategic interests in Afghanistan in that they may signal a perpetual Afghan dependence on U.S. aid and advice in order to retain legitimacy. Secondly, although high-ranking U.S. officials may insist that Ghani is not Karzai, we may never know how our working relationship with Ghani may unfold.

Thus, even as we continue to provide security assistance to the Afghan government, we should provide Kabul with the means to become less dependent on foreign aid. Although former National Security Advisor Stephen Hadley may be correct to argue that we need to continuously provide Afghanistan with diplomatic and economic stimulus packages “so that the Afghans don’t sink,” a more pragmatic approach would be to encourage the Ghani administration to engage its neighbors economically and diplomatically so that Afghanistan may become self-sufficient in the long-run.

Do Not Attempt to Change How Afghans Want to Live

Despite copious amounts of military materiel aid offered to the ANSF, and despite years spent attempting to implement a Western-style democracy and to impose rule of law upon Afghanistan’s own citizens, such attempts amounted to hollow failures at best, and may have even exacerbated the degree of corruption within Afghanistan. As if to bear this out, in his 2009 book, The Accidental Guerrilla, Kilcullen quotes an Afghan tribal leader who asked him why Americans want to bring democracy to Afghanistan through national election when they “already have democracy…but at the level of the tribe.”

Thus, given that any attempt to impose concepts foreign to the local Afghan citizens will breed resentment and hostility, we should let them figure out how they want to live. Although I do not agree with former Afghan Interior Minister Ali Ahmad Jalili’s calls for establishing rule of law that is facilitated by the United States, he is correct to note that the “Afghan society needs to be mobilized in pursuit of what its population aspires to.” Indeed, retired Marine Major Peter J. Munson may have been right when he notes that that democracy “is just a form of government that, like all other forms, can be corrupted and lost.”

Foster A “New” Coalition

Because waging a protracted counterinsurgency warfare through nation-building is a costly endeavor, and because the foreign policy options available at the U.S. disposal is still circumscribed by limits to its economic and military capabilities, another alternative that the U.S. should consider is to build a coalition involving Afghanistan’s neighbors.

After all, as the Afghanistan Study Group argues in its memo, “Despite their considerable differences, [Afghanistan’s] neighboring states…share a common interest in preventing Afghanistan from either being dominated by any single power or remaining a failed state that exports instability.” Thus, the United States must work with Iran and China since both have vested interests in containing the spread of jihadist struggles.

Furthermore, although Pakistan has proven difficult to work with, we should nevertheless continue to work with them by cajoling and flattering them. Although Max Boot of the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) advocates a sterner approach towards the intransigent Pakistani government, his recommendation is flawed because he does not seem to be cognizant of the fact that the stubborn approach by the U.S. may be the source of Islamabad’s uncooperative attitude towards the United States.

Secondly, continued impatience towards Pakistan may backfire in that, in the event that the Pakistani government should succumb to the jihadists, the jihadists may acquire CBRNe (Chemical, Biological, Radioactive, Nuclear and high-yield explosives) capabilities that may threaten the United States and Afghanistan’s neighbor.

Be Prepared to Negotiate With the Taliban

Next, in order for the U.S. to enjoy a wider range of strategic options, the U.S. should be prepared to negotiate with the Taliban. Negotiation with the Taliban is crucial because it may lessen the impact of the jihadist movement in Afghanistan, and also because it may eventually bolster the shaky legitimacy of the Afghan government in Kabul should it successfully coopt the Taliban. Viewed in this light, the updated edition of the Army/Marine Corps COIN Field Manual, FM 3-24, despite its intrinsic flaws, may be correct to note that “While it is unlikely counterinsurgents will change insurgents’ beliefs, it is possible to change their behavior…In other words, counterinsurgents must leave a way out for insurgents who have lost the desire to continue the struggle.”

Already, the prospects for meaningful negotiations look promising. Although the U.S. government failed to capitalize on this due to vociferous opposition from Karzai and the State Department, in 2013, the Taliban accepted the U.S. offers to resume negotiations in Doha.

Also, in light of the fact that President Obama has announced that the United States is prepared to communicate with terrorists to safeguard U.S. citizens, there is little reason not to negotiate with the Taliban.

Given the fact that the Taliban and ISIL/DAESH appear to be waging “mutual jihads” against each other, negotiating with the Taliban to contain jihad within the Af-Pak region may become all the more important.

Bolster Homeland Security

Last but not least, in order for the minimalist strategy meant to contain the jihadist threats to work, the United States must be prepared to defend the homeland against all possible threats including homegrown terrorists.

The U.S. can monitor and prevent terrorist attacks from within by expanding the reserve components of the U.S. Armed Forces and with improved intelligence and surveillance capabilities. Although the U.S. should maintain a minimal military presence in Afghanistan to contain and selectively target jihadists, military presence abroad will not serve any meaningful purpose within the overarching paradigm of U.S. national security strategy if the United States cannot protect its own citizens at home.

Conclusion

The picture that emerged from my case study of the Obama administration’s prosecution of its Afghan War strategy was that, from the beginning, President Obama inherited the strategic constraints and assumptions from his predecessors. This meant that the president never had a preconceived strategy for solving the festering Taliban insurgency.

Nonetheless, he deliberated on options offered to craft appropriate solutions as he saw fit. Thus, the president continued to make adjustments to his national security strategy as needs arose. The fact that his penchant for improvising led to questionable outcomes that continue to limit his geostrategic options notwithstanding, it also meant that he was capable of devising flexible and nuanced approaches to complex problems that do not offer easy solutions.

Throughout this paper, I advocated adopting a pragmatic minimalist approaches to contain the jihadist threats from the Af-Pak region. I suggested that the president should not completely withdraw military presence from Afghanistan, and that he should work with President Ghani so that he may become less dependent upon U.S. aid. I also recommended that the U.S.

should allow Afghan people figure out for themselves how they want to live, and advocated that the U.S. should form a “New Coalition” comprised of Afghanistan’s neighboring states which include Iran, China, and Pakistan. However, in order for the minimalist strategy to truly work, the U.S. should also be prepared to negotiate with the Taliban, and bolster homeland defense here at home.

It is premature to declare with certainty how events will unfold. We cannot be certain whether the Taliban, or for that matter, ISIL/DAESH will wither away, or that they will succeed in toppling the current Ghani regime in power. Nor, as we saw in my case study, can we say that the U.S. commitment in Afghanistan will end in a similar manner to the Vietnam War, because the U.S. is still committed to containing the jihadist threat by training, advising and assisting ANSF through its military presence. Nonetheless, by adopting flexible approaches to the seemingly intractable and interminable conflict in Afghanistan, we may minimize undesirable outcomes that may further circumscribe or even harm U.S. interests.

NOTE: This policy paper is based on a term paper I wrote for Dr. Joseph Szyliowicz’s Middle East and U.S. National Security class at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver. I am especially indebted to Dr. Joseph Collins, the Director of the Center for Complex Operations at the National Defense University, where I was fortunate enough to intern throughout this summer, for reading my manuscript repeatedly and offering me his invaluable insights. With that said, this paper does NOT represent the views of the Center for Complex Operations, but is a product of my own research.

This essay appeared in the Small Wars Journal

Comments Off on A case for pragmatic, minimalist approaches to the Afghanistan war

December 10th, 2013

By Jeong Lee.

The Republic of Korea has announced plans to buy up F-35 Joint Strike Fighters weeks after the program nearly went off the rails. But buying the warplanes won’t tip the balance against South Korea’s powerful regional rivals.

After facing vociferous opposition from the ROK Air Force’s retired chiefs of staff, Seoul delayed its KFX (Korea Fighter eXperimental) program by voting down competing F-15SEs “due to lack of its radar-evading functions,” according to Xinhua.

Then, on Nov. 22, the ROK Joint Chiefs of Staff announced it will purchase 40 F-35s after all—two overstrength fighter squadrons, or roughly one fighter group—as part of the KFX program. According to Aviation Week, additional 20 fighters “not necessarily F-35s, may be ordered later, subject to security and fiscal circumstances.”

The announcement came with curious timing. China recently demarcated an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the East China Sea and declared that any aircraft entering the ADIZ must file its flight plan in advance to Chinese authorities—and comply with their instructions.

But for South Korea, it’s a thorny problem. According to one ROKAF fighter squadron commander, who preferred his name not be used, the risks of confronting regional rivals like China and Japan are still far too high.

“While Japan and China may be our potential rivals someday, it never pays to antagonize them since an all-out confrontation involving any of the two states will prove deadly,” the squadron commander told me.

A ROKAF fighter pilot on the receiving end of Japanese or Chinese aerial onslaught might find himself encumbered by elaborate rules of engagement which may limit his freedom of action. This is coupled with a strategic imbalance in East Asia where both Japan and China clearly outspend South Korea on defense. Indeed, although the lieutenant colonel remained mum on his choice of fighters, he was mindful of Japan’s planned acquisition of the F-35s and China’s indigenous production of the J-20 fighter.

But according to the lieutenant colonel, the air force’s acquisition of stealth fighters sends an unequivocal message that Seoul is serious about countering China—and asserting its sovereignty over disputed territories such as the islands of Ieodo and Dokdo/Takeshima.

“It is only natural that we prefer such wondrous aircraft because they give us the capability to surreptitiously strike at the heart of our adversaries and guarantee our survivability,” he said.

For the ROKAF, there’s also the issue of numerical mass versus qualitative advantage. When I asked the lieutenant colonel if the ROKAF is willing to replace its aging fleet of third-generation fighter jets with unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs), he said the UCAVs will not satisfy ROK’s need for numbers as well as quality.

That is, given the likelihood of all-out conventional war with North Korea, fielding UCAVs may have marginal effect at best on Seoul’s ability to blunt a massive North Korean armored blitzkrieg.

Likewise, equipping a fighter group with F-35s without support from its sister fighter squadrons will also not satisfy the need for mass in the event of a lethal clash involving China or Japan.

There’s another risk inherent in “structural disarmaments.” This is a term that refers to when newer airplanes become more advanced—and more expensive to purchase and maintain—than preceding generations. The result is that a country’s air force ends up fielding fewer and fewer fighters, causing the ROK military to be spread thin, and limit its ability to respond to territorial rows with its neighbors.

In short, notwithstanding supposedly enhanced capabilities due to its acquisition of stealth fighters, the South Korean air force still lacks a coherent operational and strategic blueprint. Any South Korean response—to incidents over the islands of Ieodo or Dokdo/Takeshima for example—will likely remain limited in scale and symbolic by nature.

Indeed, a case can be made that the KFX program is mostly political posturing aimed at domestic audience as much as it is a reaction to perceived threats posed by its powerful neighbors.

South Korea’s politicians and strategic planners would do well to remember this next time they decide to plan another expensive arms purchase. They must prioritize strategic and operational planning over hardware acquisition—or get used to its military strength remaining out of balance.

(NOTE: This article originally appeared at War Is Boring on December 3rd but was later retracted. It is now cross-posted atOffiziere.ch.)

No Comments "

November 29th, 2013

I get tired of rehashing the same old argument time and again but feel that I must do so yet another time. Of late, I have been getting a lot of feedback on my ground forces merger piece— some positive but mostly negative.

Lest I be misunderstood, I welcome heated and passionate exchanges of ideas. Such discourses are evidence of healthy democracy at work which help to keep things in perspective. In short, robust discussion is what keeps the national security establishment on the cutting edge.

However, it seems that many of my strident critics tend to focus on the operational and tactical minutiae and quaint service traditions when advocating the need for maintaining two separate ground forces. One blogger seemed miffed that my piece does not fully take into account the fundamental differences in raisons d’être and functions between an Army Brigade Combat Team and a Marine Regimental Combat Team. And furthermore, he declaimed in a condescending manner that my piece overlooks the importance of “ability to fight combined arms and services” which enables the troops to possess “overwhelming combat power, both to quickly achieve objectives, and minimize losses to our force.”

To this, I should point out that even though both the United States Army and the Marine divisions successfully delivered a crushing blow to Saddam Hussein’s ragtag army in the early days of its invasion of Iraq through “shock and awe,” they found themselves ultimately mired in protracted and unwinnable counterinsurgency campaigns, not necessarily because of insufficient boots on the ground or the failure to execute counterinsurgency (COIN) operations, but because policymakers were incapable of accurately gauging the desire of “the inhabitants of the Islamic world…[who have become] increasingly intolerant of foreign interference.” Also, his assertion is intrinsically flawed in that it overlooks the unpleasant truth that “the size of the armed forces is not the most telling metric of their strength.”

Worse still, in a risible attempt to rebut my arguments, one reserve Marine captain cites as one of his counterarguments the Marine Corps’ invention of the vertical envelopment tactics during the Korean War to justify his purported “truth” that “a market place of defense ideas is better than a command economy for strategy.” However, the captain blithely ignores in his tired recitation of historical precedents that air mobile warfare, wherein armed gunships provide tactical fire support for the infantry troops, was perfected by the Army and not the Marine Corps during the Vietnam War.

This does not even take into consideration the fact that many of my critics fail to understand the difference between expeditionary warfare and costly protracted occupation of sovereign territory. As I pointed out in my response to my readers, expeditionary warfare is of short-term nature meant to shock the enemy into submission while a protracted occupation of a foreign territory entails a long-term commitment. As recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan show, however, Marines have been performing anything but expeditionary warfare. Instead, they have served as an adjunct to the Army. The same was true during the Vietnam War where regiments from 1st and 3rd Marine Divisions established firebases all over South Vietnam.

Most importantly, many of my critics do not understand that in times of waning national power, there is a better alternative to strident militarism which only alienates the global citizens from the United States. Indeed, Professor Andrew Bacevich, Colonel Gian Gentile, and Tom Engelhardt are correct when they advocate that the United States should pursue “a strategy that accepts war as a last resort and not a policy option of first choice.” This requires that the United States focus on defending the homeland first before seeking to project its finite military might abroad. Given that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have discredited the efficacy of finite military power, it would suit America’s interests to reorient its military towards homeland defense and perhaps pare down its size and functions through a service merger.

Indeed, sorely lacking in criticisms levied against my piece is any discussion on the need to redefine and reorient America’s strategic interests. It shocks me that none of my critics even bothered to ask if the United States really needs to police the world when it doesn’t even have the wherewithal to fix its own dysfunctional government. Contrary to the argument that globalization dictates that the United States should continue to maintain military bases abroad to safeguard its commercial interests because “security, prosperity, and vital interests of the United States are increasingly coupled to those of other nations,” it should be noted that many advanced, industrialized maritime nations such as China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and Britain are interconnected but are capable of safeguarding their economic interests without stationing their Marines and soldiers on foreign soil.

Even more important, the United States should make good use of its soft power—its traditional strong suit. It used to be that people around the world admired what the United States stood for: economic justice, wealth, high quality education as represented through its prestigious research universities and think tanks, high-tech inventions and tolerance for others. However, after having traveled all over Asia, I am not sure that our Asian allies even take the United States seriously.

If you don’t believe me, just ask Secretary Kerry who recently complained about “jokes [emanating from our allies] about whether because we weren’t being paid, one country or another could buy our meals.” This should serve as a sobering reminder to the defense establishment as to what America’s true priorities should be.

(Note: This article originally appeared on Small Wars Journal)

No Comments "

November 25th, 2013

By Jeong Lee.

I’ll be up front with you. As much as I aspire one day to become one, I am not a foreign policy maven. In fact, as a schoolteacher, I spend most of my days teaching in the classroom, or grading assignments in the teachers’ office. As someone who is passive and skittish, I seldom voice my opinions in public.

However, recent political and economic woes within the United States have forced me to speak my mind. Heretofore, my blog entries tended to be parochial in scope, focusing mostly on security dilemmas involving the US-ROK alliance and my life as an English teacher in the ROK. It was not until May, 2011, when the United States federal government faced the possibility of a shutdown that I forced myself to reexamine broader issues. I had to rethink with cold disinterestedness the ramifications of the extant unipolar hegemony led by the United States.

In hindsight, I think my soul-searching began in 2008 at the onset of the Great Recession. Up until then, I must admit that I subscribed to the view that the United States—and the Bush Administration—stood for justice, truth, and righteousness. Even when Rumsfeld, Cheney and other neocon policy wonks stridently advocated yet another preemptive war against Iran in 2008, I quietly nodded in approval. After all, so my reasoning went, anyone who challenges America’s status as the de facto “GloboCop” deserves to be punished. In short, I had been a believer and a naïf. What prompted the shift in my beliefs and weltanschauungs was the realization that I duped myself all along into believing that one “chosen” nation which stood “on a hill” could right all the wrongs in this world only if it exercised its God-ordained might.

The truth, I later learned the hard way, is that might does not make right. If nothing else, recent events have taught me that a nation’s dazzling display of its might is bound to run its course.

In search for answers, I embarked on a personal “tutorial” with great historians and journalists. As I savored and devoured voraciously their brilliant, yet at times, flawed treatises, I have reached the following conclusion: That try as they might to deny this incontrovertible fact, all nations are subject to what Reinhold Niebuhr, in his book, The Irony of American History (1952), calls the “vicissitudes of actual history” as both agent and creator. In other words, all nations undergo cycles of rise and fall triggered by external forces, as well as conditions wrought by their own efforts.

In this sense, one could argue that Michael Hirsh’s book, At War With Ourselves (2003), and General Tony Zinni’s book, The Battle for Peace (2006), misread history, for through their callow if not shallow analyses, they seemed to evince interests only in matters pertaining to tactical issues and seemed to hew to the view that America alone is called upon to effect positive changes in this so-called “New World Order.” But one must bear in mind that the two authors’ books merely reflected the rosy, optimistic worldview and zeitgeist then prevalent at America’s perceived zenith.

On the other hand, Amy Chua’s flawed work, Day of Empire, offers somewhat sober analysis on the rise and fall of the so-called “hyper powers.” In it, she dutifully hews to the ancient “dynastic cycle” theory which postulates that empires rise or fall due to the “mandate” from heaven—ie. legitimacy obtained from the people. According to this view, an emperor or a dynasty is stripped of this mandate when he or it undergoes stagnation, or loses his or its ability to govern due to a combination of natural disasters, internecine conflicts, or foreign invasions. In her disjointed narratives, she equates this mandate with the presence of “glue.” That is to say, the ability of an empire or an emperor to tolerate, if not embrace, cultures not its or his own. While Chua adheres to the premise that Pax Americana will continue—for the good of Mankind!—she nonetheless warns her readers that the day America strips itself of its “glue,” it will strip itself of its ideals, raisons d’être, and eventually, its very existence.

However, her “prophecy”—if one can call it as such!—seems irrelevant in light of America’s current woes. For one thing, the present American crisis was not precipitated by the absence of “glue.” In fact, America was and still remains a very tolerant and secular nation. As events unfolded before my eyes from 2008 onwards, it became obvious that America’s penchant for quick fixes, which manifests itself through American propensity to worship military might and America’s wanton profligacy, was to blame for its troubles at home and abroad. Viewed in this light, I believe that the Boston University historian Andrew Bacevich’s 2008 book, The Limits of Power, perhaps offers the best diagnosis for America’s present ills, while Fareed Zakaria’s 2008 book, The Post-American World[1], offers sound advice for what lies ahead. In both cases, their strength lies in their trenchant historical analyses which are rooted in their understanding that America served and continues to serve as “agent” and “creator” of “vicissitudes of actual history” in the making.

Granted, America is and will continue to be a global powerhouse. Recent events have shown that America remains deeply wedded to the world it helped to create in the aftermath of World War II and in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union. In the not so distant future, the United States will be a and not the sole global powerhouse because it has reached its limits as a hyper-power. And unless American citizens stop deluding themselves and see themselves for who they really are, I fear that they will lose their sacrosanct right to freedom, justice, and pursuit of happiness—the very things they treasure most.

For those reasons I decided to speak my mind. Because I subscribe to the view that American citizenry has always been the backbone and the strength of this great nation, and because I believe that the United States still has a role to play in the new world of order of the 2010s and beyond.

I shall not rest until my voice and those of other like-minded dissenters are heard.

___________

No Comments "

August 13th, 2013

By Jeong Lee.

(This article was republished by permission of the United States Naval Institute Blog and appeared in its original form on August 12th here.)

Five months after the much-dreaded sequestration went into effect, many defense analysts and military officials alike are worried about the negative repercussions of the drastic budget cuts on military readiness. In his latest commentary, the rightwing commentator Alan Caruba declared that “The U.S. military is on life support.” Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel also argued in his Statement on Strategic Choices and Management Review (SCMR) that “sequester-level cuts would ‘break’ some parts of the strategy, no matter how the cuts were made [since] our military options and flexibility will be severely constrained.”

|

| Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel answers reporters’ questions during a Pentagon press briefing on the recent Strategic Choices. Navy Adm. James A. Winnefeld Jr., right, vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, joined Hagel for the briefing. (DOD photo by Glenn Fawcett) |

To its credit, the SCMR seemed to hint at operational and structural adjustments underway by offering two options—trading “size for high-end capacity” versus trading modernization plans “for a larger force better able to project power.” Nevertheless, one important question which went unasked was whether or not the US Armed Forces alone should continue to play GloboCop.

The current geostrategic environment has become fluid and fraught with uncertainties. As Zhang Yunan avers, China as a “moderate revisionist” will not likely replace the United States as the undisputed global champion due to myriad factors. As for the United States, in the aftermath of a decade-long war on terror and the ongoing recession, we can no longer say with certainty that the United States will still retain its unipolar hegemony in the years or decades to come.

That said, Secretary Hagel is correct that the United States military may need to become leaner in the face of harsh fiscal realities. To this must be added another imperative: The US Armed Forces must fight smarter and must do so in ways that may further America’s strategic and commercial interests abroad.

So how can the United States military fight smarter and leaner?

|

| Possible Combatant Command Realignments |

First, given massive troop reductions whereby the Army personnel may be reduced to 380,000 and the Marine Corps “would bottom out at 150,000,” while at the same, the DoD is seriously considering restructuring existing Combatant Commands (COCOMs), it no longer makes sense to deploy or train troops for protracted counterinsurgency campaigns or foreign occupations. Instead, should another transnational terrorist group or a rogue state threaten homeland security, the United States could rely on SOF (Special Operations Forces) commandos and UAV (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles) to selectively target and neutralize potential threats. While the SOF and UAV surgical raids should not be viewed as substitutes for deft diplomacy, they can provide cheaper and selective power projection capabilities.

Second, since the United States Navy may be forced to “reduce the number of carrier strike groups from 11 to 8 or 9,” it can meet its power projection needs by encouraging cooperation among its sister navies and by bolstering their naval might. One example of such partnerships would be to form a combined fleet whereby America’s sister navies “may share their unique resources and cultures to develop flexible responses against future threats” posed by our adversaries.

Third, the United States may encounter more asymmetric threats in the form of cyber attacks, CBRN (Chemical, Biological, Radiation, Nuclear) attacks, and may also be vulnerable to attacks from within by homegrown terrorists and drug cartels—all of which may wreak havoc and may even cripple America’s domestic infrastructures. As retired Admiral James Stavridis argues, such asymmetric attacks may stem from convergence of the global community. Such threats require that the United States take the fight to its adversaries by cooperating with its allies to “upend threat financing” and by strengthening its cyber capabilities.

Fourth, where rogue states such as Iran, Syria and North Korea, are concerned, the United States could implement what General James Mattis refers to as the “proxy strategy.” Under this arrangement, while “America’s general visibility would decline,” its allies and proxies would police the trouble spots on its behalf.

Fifth, the United States must be prepared to defend homeland against potential missile attacks from afar. The United States may be vulnerable to hostile aggressions from afar following North Korea’s successful testing of its long-range rocket last December and Iran’s improved missile capabilities. Thus, improving its missile defense system will allow greater flexibility in America’s strategic responses both at home and abroad.

Last but not least, the United States Armed Forces needs to produce within its ranks officers who are quick to grasp and adapt to fluid geostrategic environments. One solution, as Thomas E. Ricks proposes, would be to resort to a wholesale firing of incompetent generals and admirals. However, it should be noted that rather than addressing the problem, such dismissals would ultimately breed resentment towards not only the senior brass but civilian overseers, which will no doubt exacerbate civil-military relations that has already soured to a considerable degree. Instead, a better alternative would be reform America’s officer training systems so that they may produce commanders who possess not only professional depth but breadth needed to adapt to fluid tactical, operational, and strategic tempos.

|

| “The US Military Establishment’s Greatest Foes” By Jack Ohman/Tribune Media Services |

Despite the hysteric outcries from the service chiefs and many defense analysts, in the end, the sequestration may not be as dire as it sounds. In fact, Gordon Adams argues that after several years of reductions, “the defense budget…creeps upward about half a percentage point every year from FY (Fiscal Year) 2015 to FY 2021.” Simply stated, one way or the other, the US Armed Forces may eventually get what it asks for–as it always has been the case. Nonetheless, the sequestration “ordeal”—if we should call it as such—offers the US military object lessons on frugality and flexibility. Indeed, American generals and admirals would do well to listen to General Mattis who recently admonished them to “stop sucking their thumbs and whining about sequestration, telling the world we’re weak,” and get on with the program.

No Comments "

July 30th, 2013

By Jeong Lee.

(This article is cross-posted by permission of the United States Naval Institute Blog and appeared in its original form on July 25th here.)

According to the Yŏnhap News Agency last Thursday, ROK Defense Minister Kim Kwan-jin “confirmed…that he had requested the U.S. government” to postpone the OPCON (Operational Command) transfer slated for December, 2015. Citing from the same source, the National Journal elaborated further by saying Minister Kim believed that the United States was open to postponing the transfer because “a top U.S. government official leaked to journalists” Minister Kim’s request for the delay.

There may be several reasons for the ROK government’s desire to postpone the OPCON transfer. First, the critics of the OPCON transfer both in Washington and the ROK argue that this transition is “dangerously myopic” as it ignores “the asymmetric challenges that [North Korea] presents.” Second, given the shrinking budget, they argue that the ROK may not have enough time to improve its own C4I (Command, Control, Communications, Computer and Intelligence) capabilities, notwithstanding a vigorous procurement and acquisition of state-of-the-art weaponry and indigenous research and development programs for its local defense industries. Third, South Korea’s uneven defense spending, and operational and institutional handicaps within the conservative ROK officer corps have prevented South Korea from developing a coherent strategy and the necessary wherewithal to operate on its own. To the critics of the OPCON handover, all these may point to the fact that, over the years, the ROK’s “political will to allocate the required resources has been constrained by economic pressures and the imperative to sustain South Korea’s socio-economic stability and growth.” As if to underscore this point, the ROK’s defense budget grew fourfold “at a rate higher than conventional explanations would expect” due to fears that the United States may eventually withdraw from the Korean peninsula. It was perhaps for these reasons that retired GEN B. B. Bell, a former Commander of the United States Forces Korea, has advocated postponing the transfer “permanently.“

However, the Obama Administration’s reversal of its decision to hand over the OPCON to the ROK military appears unlikely. First, in the face of the drastic sequestration cuts in the upcoming fiscal years, long-term commitment in the Korean peninsula may be unsustainable. Second, since both the United States Armed Forces and civilians suffer from war-weariness after having fought in Iraq and Afghanistan for over a decade, it is unlikely that they will accept long-term overseas commitment of this magnitude. Which leads to the third point that the United States will likely favor diplomatic solutions when dealing with Kim Jŏng-ŭn, since the DPRK has recently expressed its desires to engage in dialogues. Fourth, “[m]ost economic and military indicators show that South Korea has an edge over North Korea in almost all measures of power.” While many opponents of the transition point to the DPRK’s asymmetric threats to make their case, Suh Jae-jung contends that “quantitative advantage quickly fades when one takes account of the qualitative disadvantages of operating its 1950s-vintage weapons systems” which has led “serious analysts [to] conclude that ‘North Korea never had a lead over South Korea.’” Most importantly, arguments against the scheduled transition are weak because they tend to focus only on the military dimensions of the ongoing conflict.

There are several ways in which the US-ROK alliance can enhance security dynamics on the peninsula in the aftermath of the OPCON transfer. One obvious approach would be to seek diplomatic solutions to proactively deter further provocations by Kim Jŏng-ŭn. Despite the deep-seated rancor and distrust between the two Korean states, both Korean states have nevertheless agreed to reopen the Kaesŏng Industrial Complex. The latest inter-Korean talk held at P’anmunjŏm demonstrates more than anything else the need to “cajole and flatter the young ruler…[by] allowing Kim Jŏng-ŭn to save face as sovereign ruler of his country.” As Miha Hribernik and I wrote in June, one way of doing this would be to “accept his offers to discuss arms reduction first.” In addition, the US-ROK alliance could defuse tension on the Korean peninsula by recognizing the DPRK as a sovereign state. Such measures would prevent miscommunication where parties involved are “not talking to each other but rather, past each other.”

Nevertheless, the US-ROK alliance must avoid appearing weak even as it seeks diplomatic solutions to guarantee peace and security for the Korean peninsula. As I wrote earlier, “in order for diplomatic endeavors to be sustainable in the long-run, they must be backed up by a credible threat of coercion.” With or without the OPCON, there are several ways in which the US-ROK alliance can effectively deter future DPRK aggressions. One such option, as I’ve written earlier, would be for the United States Pacific Fleet and the ROKN, along with the JMSDF, to form a combined fleet whereby the three navies “would may share their unique resources and cultures to develop flexible responses against future threats by Kim Jŏng-ŭn.” Second would be to allow the ROK JCS Chairman to assume command of the CFC with the top American general serving as his deputy as was proposed in June during a ministerial meeting held between Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel and Defense Minister Kim Kwan-jin. However, at this juncture, according to the Washington Post, “the 28,500 U.S. troops here will not fall under the command of the South…[since] the United States and South Korea will have separate commands.” Third, to proactively deal with possible DPRK missile attacks, the US-ROK alliance, together with Japan, can develop a collective missile defense system. Fourth, as retired Admiral James Stavridis argues, since the world has converged into smaller communities through globalization, we must take the fight to our adversary by “follow[ing] the money [to upend] threat financing” abroad and at home. Last but not least, since the DPRK’s recent asymmetric attacks against the US-ROK alliance have been waged on cyberspace to cripple their infrastructures, the US-ROK alliance, in tandem with the international community, can work together to enhance their cyber security.

Despite unfounded fears among retired officers and conservative analysts that the OPCON transfer may considerably weaken South Korea’s security, it does not mean that the United States will completely withdraw from the Korean peninsula. Nor does the ROK resemble South Vietnam after the Paris Treaty of 1973. That is, the ROK remains an economically and politically stable nation. With new transition come new opportunities for innovative growth. For the ROK, OPCON transfer just may present such opportunities to protect itself from further aggression by Kim Jŏng-ŭn.

No Comments "

July 20th, 2013

By Jeong Lee

In the wake of Hassan Rowhani’s landslide victory as Iran’s new president, some foreign policy mavens now believe that Rowhani’s presidency may augur a positive shift in Iran’s hitherto hostile policy towards the West. However, despite a glimmer of hope that Rowhani’s election may translate into moderate policies towards the West, others have “adopted a cautious ‘wait-and-see’ posture,” citing Rowhani’s past affiliation with the Ayatollah.

For East Asian experts, Rowhani’s election warrants attention because it remains to be seen whether Iran will retain its current alliance with Kim Jŏng-ŭn even if it chooses to reconcile with the West. After all, some have alleged that Iran has played a major role in the DPRK’s successful testing of its Ŭnha-3 rocket last December. More importantly, Rowhani’s future stance towards the West deserves attention because it may determine whether or not the United States must revise its strategy to adapt to new geostrategic realities. Indeed, it can be argued that the aforementioned factors are not mutually exclusive but intricately intertwined.

Some foreign policy mavens have construed recent events in the Korean peninsula and Iran as encouraging “game-changers.” After all, both Koreas have begun talks to ratchet down the ongoing tension. Furthermore, experts on Iran agree that Rowhani’s victory was prompted by a universal desire for positive change after years of economic hardships and political repression under Ahmedinejad.

However, geostrategic realities on the Korean peninsula and in the Persian Gulf may be more complex than they appear. On the Korean peninsula, the two Korean states evinced deep-seated rancor and mutual distrust in their latest talk held at P’anmunjŏm despite having reached an agreement to reopen the Kaesŏng Industrial Complex. As Miha Hribernik and I wrotepreviously, “Should miscommunication problems and distrust persist, the consequences for the Korean Peninsula and the regional security environment may be dire.” As for Iran, it has recently claimed to have improved the accuracy of its ASBM, the Khalij-e Fars (Persian Gulf). Further, Rowhani’s election may have little effect on Iran’s existing nuclear policy because ultimately, “it is Khamenei who will make the final decision on the nuclear program.” In other words, both the DPRK and Iran may continue their existing partnership, or even lash out against the United States, if they believe that their collective interests are threatened.

So how can the United States successfully recalibrate its existing strategy in ways that reflect current geostrategic realities in the Persian Gulf and on the Korean peninsula? Dealing with the DPRK and Iran may require a flexible combination of deft diplomacy on one hand, and a show of strength on the other. In simple terms, the United States should “speak softly and carry a big stick” when dealing with future threats posed by the DPRK-Iran alliance.

Diplomacy may be the best option that the Obama Administration has to proactively deter the two “outlier” states from coalescing. Indeed, Vali Nasr recommends offering sanctions relief to Iran so as “to break the logjam over nuclear negotiations.” Even better, the United States can thaw relations with Iran and the DPRK by granting diplomatic recognition to both countries. In addition to “reducing dangers” stemming from miscalculations and enabling the United States to gather intelligence on both countries, normalization may prevent the outbreak of a fratricidal war on the Korean peninsula and may hold Rowhani and Kim Jŏng-ŭn accountable to international norms.

Nevertheless, in order for diplomatic endeavors to be sustainable in the long-run, they must be backed up by a credible threat of coercion. While many defense analysts and strategists remainfixated on countering Iran and China’s A2AD tactics, the United States military can no longer afford to operate alone in the face of drastic sequestration cuts. It can, however, exercise firmness by “leading from behind” by working with allies and proxies. One such example is that of a “proxy strategy” implemented by General James Mattis whereby Iran’s Sunni neighbors would supposedly vie for influence in the Persian Gulf region to deter, if not contain, Iran’s rise as a regional power. Another option, as I’ve proposed earlier, would be to form a combined fleet composed of the United States Pacific Fleet (PACFLT), the ROK Navy and the Japanese Self-Defense Maritime Force (JSDMF) to proactively deter future DPRK provocations. Third, given that the United States still faces aggression from afar in the face of improved missile capabilities possessed by Iran and the DPRK, the United States must be prepared to defend itself at home by bolstering its missile defense systems. Last, and perhaps most important, since the world has converged into a smaller community by way of globalization, we must take the fight to our adversaries by “recogniz[ing] that it takes a network to confront another network…[and, therefore, must] follow the money [to upend] threat financing” internationally and at home.

LCDR B. J. Armstrong wrote that there “would be changes to tactics, and the requisite adjustments to operational planning” when dealing with adversaries who threaten America’s strategic dominance abroad. To this, one should add that flexible strategic responses, whereby the United States readily wields a combination of carrots and sticks to deal with refractory pariah states, may be needed to guarantee America’s continued strategic dominance and peace in the Persian Gulf and in East Asia.

http://blog.usni.org/2013/07/18/speak-softly-and-carry-a-big-stick-when-dealing-with-future-north-korean-and-iranian-threats/

No Comments "

July 7th, 2013

By Jeong Lee

(Note: This article was republished by permission from the Center for International Maritime Security and appeared in its original form on June 27th here.)

The ROKS Dokdo and USS George Washington on exercise together.

In my previous entry on the U.S.-ROK naval strategy after the OPCON, I argued for a combined fleet whereby the U.S. and ROK Navies, together with the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF), may share their unique resources and cultures to develop flexible responses against future threats by Kim Jŏng-ŭn. Since I have been getting mixed responses with regards to the viability of the aforementioned proposal, I felt compelled to flesh out this concept in a subsequent entry. Here, I will examine command unity and operational parity within the proposed combined fleet.

First, as Chuck Hill points out in his response to my prior entry, should the three navies coalesce to form a combined fleet, the issue of command unity may not be easily overcome because “[w]hile the South Korean and Japanese Navies might work together under a U.S. Commander, I don’t see the Japanese cooperating under a South Korean flag officer.” Indeed, given the mutual rancor over historical grievances, and the ongoing territorial row over Dokdo/Takeshima Island, both Japan and the ROK may be unwilling to entertain this this arrangement. However, this mutual rancor, if left unchecked, could potentially undermine coherent tactical and strategic responses against further acts of aggression by Kim Jŏng-ŭn. It is for this reason that Japan and the ROK should cooperate as allies if they truly desire peace in East Asia.

So how can the three countries successfully achieve command unity within the combined fleet? One solution would be for an American admiral to assume command of the fleet. However, while it is true that the ROKN and the JMSDF have participated in joint exercises under the aegis of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, this arrangement would stymie professional growth of both the ROKN and JMSDF admirals who lack professional expertise comparable to their American counterparts. In particular, given that ROKN admirals will assume wartime responsibility for their fleets after the 2015 OPCON transfer, such arrangement would be unhealthy for the ROKN because it would only lead to further dependence on the U.S. Navy.

Instead, a more viable solution, as Hill suggests, would be for the three navies to operate on a “regular rotation schedule…with the prospective commander serving as deputy for a time before assuming command.” This arrangement would somewhat alleviate the existing tension between the ROKN and JMSDF officers. Furthermore, the rotation schedule may serve as an opportunity for ROKN and JMSDF admirals to prove their mettle as seaworthy commanders.

One successful example that demonstrates the efficacy of the above proposal is the ROKN’s recent anti-piracy operational experience with the Combined Task Force (CTF) 151 in the Gulf of Aden from 2009 to the present. In 2011, ROKN SEALs successfully conducted a hostage rescue operation against Somali pirates. ROKN admirals also assumed command of the Task Force twice, in 2010 and 2012 respectively.[1] According to Terrence Roehrig, the ROKN’s recent anti-piracy operational experience has “provide[d] the ROK navy with valuable operational experience [in] preparation for North Korean actions, while also gaining from participating in and leading multilateral operations.”[2]

However, it should be noted that it is “unclear whether ROK counter-piracy operations [with CTF 151] had a significant deterrent effect and, if so, it [was] likely to be limited.”[3] While CTF 151 may provide a plausible model for command unity for the combined fleet concept, it does not fully address potential operational and logistical problems in the event of another armed conflict on the peninsula. Moreover, while frequent joint exercises and exchange programs have lessened operational and linguistic problems, so long as the ROKN continues to be overshadowed by the Army-centric culture and structure within the ROK Armed Forces, it cannot function effectively as a vital component of the U.S.-ROK-Japan alliance in deterring future aggression by Kim Jŏng-ŭn.

To achieve operational parity within the combined fleet, I recommend the following. First, the United States could help bolster the naval aviation capabilities of both navies. The JMSDF has been expanding its number of helicopter carriers, while the ROKN is expanding its fleet of Dokdo-class landing ships, supposedly capable of carrying an aviation squadron or unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), in addition to its naval air wing. However, the absence of carrier-based fighter-bomber capabilities may pose problems for the combined fleet concept because it deprives the fleet of flexible tools to respond expeditiously to emergent threats. Thus, the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps could equip the two navies with the existing F/A-18E/F Super Hornets or the new F-35s.

Second, both Japan and the ROK should bolster their amphibious and special operations forces (SOF) capabilities. As the successful hostage rescue operation in January, 2011, of the crew of the Korean chemical tanker Samho Jewelry by the ROKN SEAL team demonstrates, naval SOF capabilities may provide the combined fleet with a quick reaction force to deal with unforeseen contingencies. Furthermore, amphibious capabilities similar to the U.S. MAGTF (Marine Air-Ground Task Force) may provide both the ROK and Japan with the capabilities to proactively deter and not merely react to future DPRK provocations. That the Japanese Rangers[4] have recently trained for amphibious landing with U.S. Marines, while the ROK MND (Ministry of National Defense) has granted more autonomy to the ROK Marines, can be construed as steps in the right direction. As if to bear this out, there are reports that the ROK MND plans to establish a Marine aviation brigade by 2015 to enhance the ROKMC’s transport and strike capabilities.

In this blog entry, I examined command arrangement and operational parity to explore ways in which a combined U.S.-ROK-Japanese fleet may successfully deter potential DPRK threats. Certainly, my proposal does not purport to offer perfect solutions to the current crisis in the Korean peninsula. Nevertheless, it is a small step towards achieving a common goal—preserving peace and stability which all East Asian nations cherish.

Jeong Lee is a freelance international security blogger living in Pusan, South Korea and is also a Contributing Analyst for Wikistrat’s Asia-Pacific Desk. Lee’s writings have appeared on American Livewire, East Asia Forum, the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, and the World Outline.

[1] Terrence Roehrig ‘s chapter in Scott Snyder and Terrence Roehrig et. al. Global Korea: South Korea’s Contributions to International Security. New York: Report for Council on Foreign Relations Press, October 2012, p. 35

[2] ibid., pp. 41

[3] ibid.

[4] Japan does not have its own Marine Corps.

No Comments "

June 16th, 2013

By Jeong Lee and Miha Hribernik

The Korean Peninsula seems to have calmed down after months of heated tension among all parties involved. Indeed, recent events may suggest that neither Korean state is willing to risk an all-out war that would provedeadly. That both the Republic of Korea (ROK) and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) held talks at Panmunjŏm last week may augur a starting point from which, according to the Associated Press, “tension is easing.” However, any optimism should be tempered in light of North Korea’s well-established track record of avoiding—or outright ignoring—negotiation overtures from South Korea.

As Lt. Col. Roger Cavazos and Peter Hayes of the Nautilus Institute noted, inconsistent approaches by all parties involved may eventually backfire and even derail any chance for reconciliation because they may lead tomiscommunication whereby parties involved are “not talking to each other but rather, past each other.” Should miscommunication problems and distrust persist, the consequences for the Korean Peninsula and the regional security environment may be dire. A breakdown in communication, followed by possible limited armed skirmishes, could also provide new impetus and outside pressure to bear on both Koreas.

During a crowd-sourced geostrategic simulation entitled “Korean Conflict Pathways,” a team of analysts atWikistrat explored what may happen if attempts by the US-ROK alliance to extend an olive branch to Kim Jŏng-ŭn backfire. According to this scenario, Kim Jŏng-ŭn, who is frustrated by what he believes to be inconsistent demands of the US-ROK alliance between offers to negotiate and insulting remarks about his “outrageous demands,” may lash out against the ROK military installation situated along the contested Northern Limit Line (NLL), setting in motion a full-fledged war. Jeong Lee and other analysts who worked on this scenario speculated that in such case, the United States and China might work together with Russia and Japan to bring the two Koreas to the negotiating table because they do not wish to be mired in a deadly regional conflict. Therefore, what may ultimately result is a mutual recognition of sovereignty between two Korean states after a devastating conflict. Simply stated, both Korean states may learn to peacefully coexist. Indeed, the potential outcomes of this simulation may reflect the possibility in which “neither the U.S. nor China is ready to see the strategic landscape in Asia changed in a fundamental way [by the recent Korean crisis].”

The aforementioned simulation scenario also revealed that North Korean threats, such as those most recently seen between March and May this year, are intended as much for internal consumption as they are for extracting concessions from the international community. If miscalculations are to be avoided, one must be always mindful of this factor because Western analyses on the inter-Korean security dynamics still do not factor sufficiently into consideration Kim Jŏng-ŭn’s need to save face and fully consolidate his grip on the Korean People’s Army.

How can the US-ROK alliance and other East Asian countries successfully bring Kim Jŏng-ŭn to the negotiating table? One way of doing this, as argued previously, is to “cajole and flatter the young ruler… [by] allowing Kim Jŏng-ŭn to save face as sovereign ruler of his country.” The US-ROK alliance could help Kim Jŏng-ŭn save face by “accepting his offers to discuss arms reduction first” in addition to holding further talks. That both Koreas have agreed to a “meeting between responsible authorities” this week may be seen as a step towards that direction. Secondly, to prevent a catastrophic regional war, the US-ROK alliance could grant formal diplomatic recognition to the DPRK as a sovereign state.

These diplomatic measures may be crucial in helping the DPRK’s Supreme Leader to save face as he continues to cement his position internally, although they alone may not suffice to prevent potential miscommunications among parties involved. Further, such measures could enable the DPRK to become a responsible member of the international community as it seeks to redirect its focus away from its Sŏn’gun (Military First) policy to economic development.

As ongoing tensions on the Korean peninsula continue to trouble security dynamics in East Asia, preventing miscommunication with Kim Jŏng-ŭn should remain a priority not only for the US-ROK alliance but also for neighboring states. However, should a complete breakdown in communication between Seoul and Pyongyang ultimately occur, a possible solution might be that China and the United States, together with Russia and Japan, jointly apply pressure on both Koreas in order to avoid a destructive regional war.

Jeong Lee is a freelance international security blogger living in Pusan, South Korea and is also a Contributing Analyst for Wikistrat’s Asia-Pacific Desk. In addition to his regular contribution for GJIA Online, Lee’s writings have appeared in American Livewire, East Asia Forum, and the World Outline.

Miha Hribernik is Research Coordinator at the European Institute for Asian Studies in Brussels and an analyst at Wikistrat. He also writes for the International Security Observer and blogs at the Japan Foreign Policy Observatory. All views expressed are his own.

http://journal.georgetown.edu/2013/06/10/how-the-united-states-and-south-korea-can-avoid-fatal-diplomatic-missteps-on-the-korean-peninsula-by-jeong-lee-and-miha-hribernik/

No Comments "