Posts by AzmiAshour:

Supremacist delusions

August 10th, 2015

By Azmi Ashour.

The methods the Muslim Brotherhood employs to attract and recruit the young may not always be clear to outsiders. But if we are ever going to understand the violent tendencies of political Islam, we must look closely into such matters.

Since its inception, the Muslim Brotherhood has been a secretive, hierarchical, ironclad group that looks down on outsiders and, if necessary, abrogates the rights of anyone who doesn’t join its ranks.

It doesn’t matter if you’re a fellow citizen or even a fellow Muslim. Unless you are part of their group, you are viewed with suspicion, denied the right to equal treatment, bullied as an atheist and denounced as a peril. For the Muslim Brotherhood, every outsider is inferior. People who work for the government are misguided because all governments are ungodly. People who work for Al-Azhar, including eminent Muslim scholars, are particularly targeted for attack because they don’t bow to the group’s narrow interpretation of the Muslim faith.

One would have thought that such narrow-mindedness would deter recruits, that such supremacist ideas so abhorrent to mainstream Muslims would discourage followers. But this, unfortunately, has not been the case. Occupying the far-right fringe hasn’t proved as distasteful to the young as one would have expected. And that’s something for which the Muslim Brotherhood is not to blame but rather, the rest of society.

When the Muslim Brotherhood takes such a hold, as evidenced by the events of the past few years, on the minds of university students, then one has to question the basics of our education system. Universities should have been our line of defence against the lunatic fringe, not our fifth column.

We’ve been asking ourselves the wrong questions. We’ve been wondering what’s wrong with people who join such extremist groups. But what we should have been asking is: Where did we go wrong? How did we produce a type of person who prefers fanaticism and violence to moderation and normalcy?

Let’s admit it. Muslim Brotherhood supporters have no use for the institutions of this country, for its traditions or for its values of tolerance and coexistence. Infused with the bigoted ideas of their group, Muslim Brotherhood followers have developed an intense repugnance not only for the government but also for fellow citizens.

And they are acting on their hate, bombing indiscriminately, disrupting normal life, blowing up power stations and anything else they consider of purpose to their fellow citizens.

This is not to say that every act of terror is carried out by the Muslim Brotherhood. But every act of terror owes its inception to the ideology of that group, an ideology that now inspires not only its members but also a wide range of lone wolves, nihilistic saboteurs and global jihadists here and elsewhere.

We’ve lived with Muslim Brotherhood-inspired violence for decades but what we see today is unprecedented. This unbridled desire to undermine the state and its institutions, to stop the economy in its tracks, to hurt and maim the public, outpaces everything we’ve seen in the past.

From the Mediterranean coast in the north to Aswan in the south, no one is safe. Metro stations, railways, electricity pylons, tourist destinations all are targets for senseless violence. Not to mention police and army personnel, whom the Muslim Brotherhood and its like-minded friends resent for trying to keep the country together.

By Muslim Brotherhood standards, anyone who wants to keep the country together is an atheist, deserving punishment not in the afterlife but immediately. Anyone working for the government is a criminal; anyone protecting the nation is a murderer.

This may seem unconscionable for a group that, when allowed to take office, wasted no time in alienating the majority of the population, so much so that within six months a million people were protesting at the Ittihadiya Palace.

Within a year of Mohamed Morsi being sworn in as president, millions more marched to demand an end to his rule. On 30 June 2013, Egypt turned a new leaf. But the Muslim Brotherhood wasn’t going to allow the country to get away with this affront against it. Self-appointed as guardians of the faith, self-anointed as missionaries of Sharia, the Muslim Brotherhood swore to strike back.

The terror we see in North Sinai today may not be all of the Muslim Brotherhood’s doing, but it has drawn on the group’s example and inspiration. Other jihadists are involved too ones that draw help from the Gaza-based Hamas movement, itself a Muslim Brotherhood offshoot. So it wasn’t enough for Hamas to undermine Palestinian unity, or misrule in Gaza. Now it’s time to take a swipe at Egypt too.

The irony of this situation is that these violent tactics actually work young men volunteer to be part of this nihilistic quest, whether propagated by the Muslim Brotherhood or by its offshoots or by third- and fourth-generation jihadists.

A young man who goes and plants a bomb under an electricity pylon, what is he thinking about? A student who departs from his studies in science or the humanities to embrace instead the supremacist ideas of the Muslim Brotherhood and its friends, what is he hoping to achieve?

It is no longer a war on terror, as people have imagined. It is no longer an attempt to catch every perpetrator and bring them to justice, although this obviously has to be done.

The issue is much deeper than that. The issue is that we haven’t immunised the young against the jihadist virus, against the nihilistic microbe, against the fanaticism of religious supremacists of multiple and ever-evolving strains. To stop the malaise we need to think back a step or two. To keep the young from being brainwashed, we have to offer them a model of contentment they can aspire to. It is not easy to fight off terrorists, but it may be even harder to keep the young from joining their ranks. This is the real battle, and it is one that families and schools, society and government have to fight together.

If we are reaping terror now it is because we have sowed the wrong seeds in the past. So let’s take responsibility now. Let’s remove the seeds of hatred and racism from the minds of the young.

Let’s teach them how to love life and respect it. Let’s teach them how to honour, how to appreciate and how to question.

Comments Off on Supremacist delusions

Syria and the rediscovery of nationhood

January 28th, 2015

By Azmi Ashour.

In the streets of Cairo, Beirut, Amman and Istanbul you can appreciate the value of having a homeland when you look into the eyes of the Syrian children and mothers begging alms from passersby.

“Cruel and miserable life,” they tell you. “We once lived among family and friends, with a secure source of livelihood, food in our mouths, a roof over our heads and a country to protect us. All that vanished.

“We then faced two choices: either to die beneath the ruins of our homes and belongings or to flee with only the air we breathe as our source of comfort, as this was the only thing that we could take without anyone asking us for something in return. But our suffering did not end there.

“We were forced to embark on another ordeal in which the risks and dangers were as great as those we would have encountered by staying at home in the rubble. Encouraged by the hope that life was possible elsewhere, far away from this nation that had become hell, we left all that we had belonged and joined others on the road to refugee camps across the borders.

“As for those of us who managed to escape to the big cities, find sympathy among some of the inhabitants and obtain the money to feed ourselves for that day (which does not always happen), life became more difficult. We had no roof over our heads and the police would round up our children who should have been with other children, in school, but instead had become street children begging for money.

“Many of them have lost their families. Whereas once they lived happy, comfortable lives, going to school every day, and were brought up normally and healthily, they are now wandering the streets of strange cities in their tattered clothes, unfamiliar with the language, crying and shivering in the bitter, merciless cold.

“What crime did they commit that caused them to lose everything from their past and future, leaving them only the air they breathe and the present moment in which they survive solely on hand-outs from some sympathetic souls?”

According to UN estimates, there are around six million Syrian refugees. These millions have been reduced to misery for the sin of having lived under a dictatorial regime that tailored the concept of the nation to suit the demands of its family, clan and sect, all others be damned.

At the same time, there was a regional and international order that found this convenient and ignored the Syrian people and anything related to them so that these powers could augment their interests. How wise the former Egyptian president was, even though he is now in prison and facing trial, for having bowed to popular pressure to step down.

As he saw it, it was better for him and his children to go to jail than for Egypt to experience the plague that has afflicted Syria.

When the Muslim Brotherhood came to power they brought with them a different mindset. Theirs was as blinkered and self-serving as that of Al-Assad, for they, too, sought to tailor the concept of the nation to the purposes of their own group and to open the doors to foreign intervention in Egyptian affairs.

The Egyptian people once again proved true to their historic greatness and ended the Brotherhood rule within a single year after having realised that it was leading Egypt down the path of the Syrian disaster. The Egyptian military establishment reflected this will and demonstrated its awareness of the true concept of nationhood as it fought to restore this concept and safeguard it from groups that were bent on igniting civil war in Egypt.

There was a price that was paid for this, whether by those who lost sight of the real picture or by the members of the army and police who were killed in terrorist attacks. It was their blood that kept Egypt from descending into civil war, which would have drawn regional and international meddlers like flies and driven millions of Egyptians to seek refuge in whatever neighbouring countries remained safe.

It was their sacrifices that safeguarded the Egyptian character that has survived for 5,000 years in spite of all the challenges and dangers that threatened to undermine it.

The revolution has helped us rediscover the meaning of the nation as a collection of institutions that should never be destroyed for the sake of a religious or utopian ideology. Among the crises that led to the collapse of Syrian — as well as Libyan — society was the absence of strong government institutions and justice and the rule of law. This is the lesson we must remember.

Yes, we must work to fight off dictatorship because it is the indirect path to the collapse of the state at some point in the future. We must therefore work to give root to democracy and all modern humanitarian values. But these aims can only be realised in the framework of the nation state and its institutions.

If these are destroyed, we will join the long queues of refugees, from the Palestinians and Iraqis and more recently the Syrians, whose plight rends our hearts, as the humanitarian tragedy they are enduring is even greater than the calamity that befell the Palestinians.

Contrary to a commonly held perception, revolution could be an occasion to rediscover existing truths that are not easily noticeable under normal circumstances. With regard to Egypt, the revolution threw into relief the meaning and value of the state.

The state is not an entity to be cut and trimmed to suit the whims and welfare of a particular individual, clan or group. It is the property of all who live beneath its skies and breathe its air.

Comments Off on Syria and the rediscovery of nationhood

The Islamic State debacle

December 1st, 2014By Azmi Ashour.

Ever since political Islam reared its head in 1928, the year in which the Muslim Brotherhood was created, it has offered more impediments to society than hope.

Its lack of substance didn’t prevent it, however, from gaining recruits. And although at heart it constantly clashed with every concept of modernity and civil standards, it aspired to govern and strove to gain power.

Political Islam was never about governing one country, for at its core it aspires to universal supremacy. Strictly speaking, any nation that succumbs to political Islam, the proponents of such ideology believe, must be used as a stepping stone to acquiring more land and bringing more people under its wing.

The idea of ustaziyat al-alam, or global moral leadership, as put forward by Muslim Brotherhood founder Hassan Al-Banna, is rather baffling. According to this notion, Muslim Brotherhood members must offer themselves as role models for the entire world. And yet, the fundamental leanings of this group seem to run in the face of everything most of humanity agrees is common decency.

That this group harbouring so much animosity towards all modern values of the world should sees itself as a global saviour is quite intriguing. And yet various strands of the political Islam that the Muslim Brotherhood propagated still act as if they are entitled to world domination by dint of what they believe is a morally superior past.

From its outset, the Muslim Brotherhood developed a knack for assassinations. Opponents as well as top statesmen were mowed down by its armed outfits. And the spiral of radicalism this group started is still spawning horror to this day. Since the 1970s, splinter groups from the Muslim Brotherhood embraced increasingly radicalised notions of religion, lifestyle, and government.

The political Islam groups of the 1970s, operating still in Egypt, assassinated a minister of religious endowments, or awqaf, and then killed President Anwar Al-Sadat — a man who ironically relied on the Islamists to undermine his leftist opponents.

The wave of violence that these groups initiated continued unabated throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the stage was set for another wave of political Islam, one that was more radicalised than the one before. As many young men left their countries to join the jihad against the Soviets, the war in Afghanistan offered them opportunities that were lacking in their own countries.

The veterans of the Afghanistan war brought extremist ideas not only to Egypt but also to most Arab countries. And a new generation of jihadists appeared across the region, where tyrannical regimes held on to power but offered no hope for true progress.

As the 20th century drew to a close, Al-Qaeda had already branched out in various Arab countries. Sudan in particular became a playground for Al-Qaeda operatives. And Algeria was subjected to a particularly bloody challenge from radical Islamists.

Then 9/11 sent the world into shock, triggering another wave of radicalism, one that was played out on a much larger scale, and with increasing brutality. As the Americans sent troops to occupy Afghanistan and Iraq, the jihadists gained momentum. The collapse of central government in Iraq was a bonus to radical groups that had no chance of challenging the watertight police state that had been in control of that country for decades. The rebirth of Al-Qaeda in Iraq was instantaneous and so far irreversible.

Iraq was disfigured by the occupation, and before long the country was torn apart by competing local and regional powers. Ethnic rivalry, religious sectarianism, and the special interests of countries such as Iran and Saudi Arabia weren’t conducive to Iraq’s unity or stability. And in the maze of shifting loyalties, radical Islam flourished.

The next wave was to be even worse. The Arab Spring, born in hope, ended up in disappointment as in one country after another. As the tyrants fell, the Islamists sprang into action.

No longer deterred by the police states of the past, the Islamists hijacked the revolution in both Egypt and Syria, alternately by ballots and bullets.

In both Egypt and Tunisia, Islamists managed to win elections but had trouble delivering on the promise of the revolution, having no use for the democracy and freedom that was supposed to follow the overthrow of authoritarian regimes.

As the Muslim Brotherhood rose to power in Egypt it developed a knack for intimidating its opponents. Not satisfied with controlling the government, the group had its radical allies bully judges and journalists. The sieges on Media City and the High Constitutional Court that followed were prolonged, and the Brotherhood encouraged rather than curbed this challenge to the country’s civil institutions. For the entire year the Muslim Brotherhood remained in office it treated with disdain the very institutions of the state it was supposed to protect.

By 30 June 2013, the people had had enough and they came out in numbers to demand the army intervention that ousted the Muslim Brotherhood from power.

One can only wonder what would have happened had the army not intervened. Just before being removed from office, President Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood urged a jihad in Syria — a move that could have only strengthened the hand of militant Islam back home.

The Islamists saw their chance and took it. But this is not to say that Arab societies are not to blame. The fertile soil for extremism is not confined to one Arab country, but exists throughout the region. The failure of tyrannical regimes to meet the expectations of their people furnishes the basis for discontent that the Islamists have grown adept at exploiting.

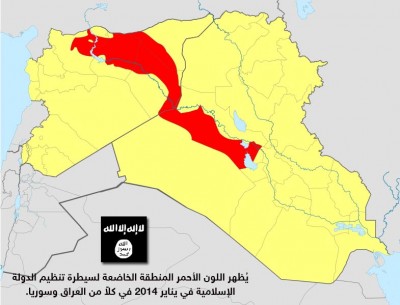

The emergence of the Islamic State, perhaps the ultimate form of disfigured militancy that political Islam has ever created, is proof that the political vacuum in both Syria and Iraq was complete. The fall of Saddam and the rapid erosion of Al-Assad’s power paved the way to radicalism on an unprecedented scale.

Many had assumed that the power vacuum left by the demise of tyrants would open windows for freedom. But events in Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere proved the opposite to be true.

The jihadists rose high in Syria and Iraq, but they were denied Egypt, their most coveted objective. In both Syria and Iraq, the radicals won ground only after the collapse of central power.

In Egypt, they are still trying to bomb and intimidate, although the country managed to keep its central power intact. Such is the desire to control Egypt, and such is the despondence at its loss, that the radicals are still fighting what until a few years ago would have been considered a hopeless battle.

This shows how determined the radicals are. They may be short on substance when it comes to common sense and compassion, but they are not short of support.

There are 3,000 Tunisian, 2,500 Saudi, and 2,000 Jordanian jihadists currently fighting under the Islamic State banner, according to available estimates.

Until recently, measures to stop the flow of combatants to war zones have been lax and clerics failed to denounce Islamic State crimes. This is changing as time goes by. But the fact is that the Islamic State used the same militant ideology that three generations of political Islam have used before it. The fault with political Islam is not confined to the Islamic State, for the twisted ideas have been around for decades, and so has the fertile soil of discontent.

Comments Off on The Islamic State debacle

Justice and the Muslim Brotherhood trials

November 18th, 2014

By Azmi Ashour.

Critics have charged that Egypt’s judiciary is politicised but appear to have no evidence to support their claim, writes

The mass death sentences handed down against a number of defendants from the Muslim Brotherhood and similar organisations that were tried on charges of mass murder triggered considerable controversy. Not only did they occasion harsh criticism of the Egyptian judiciary at home and abroad, but they also were used as a pretext to attack those who are currently ruling Egypt.

Yes, the judiciary may have shortcomings, as is the case with any other institution. However, this does not refute this branch of government’s long-established institutionalised performance and deeply rooted dedication to serving the principle of justice. Furthermore, this is despite the abuses it was subjected to by those in power over the past decades.

The notorious “judges massacre” that took place under Abdel Nasser, similar, albeit subtler actions undertaken during the Mubarak era, and even the Muslim Brotherhood’s year in power when the judiciary became the victim of the blockade of the Supreme Constitutional Court, the threat to force senior judges into early retirement to clear the bench for a new generation of Muslim Brotherhood indoctrinated judges, and other forms of harassment, did not divert the judiciary from its commitment to its duties.

It continued to supervise elections, including those that brought Morsi to power and the recent presidential elections, and its various courts continued to hear and issue verdicts on the innumerable cases brought before them.

In its many hearings in recent years, the judiciary made no exceptions, not for Mubarak and his regime (the nature of which is familiar to all), nor for the Muslim Brothers, nor for the activists who were found guilty of violating certain laws, even if the constitutionality of some of those laws (the so-called protest law) has been called into question.

Therefore, it is difficult to find any basis for the sweeping judgement that claims that the Egyptian judiciary issues “politicised verdicts”. This is all the more so in view of the entire process of arraignments, investigations, the questioning of witnesses, examining of evidence, hearing arguments and counter arguments, all in order to determine in a systematic, scientific manner whether defendants are guilty. This attention to detail and process is rarely found in the work culture of other institutions.

True, some defendants may be wrongfully found guilty due to the lack of evidence that would prove their innocence. However, the strict adherence to the established set of legal rules and processes, even if an individual or a group might be adversely affected, is a victory for the impartiality of justice in procedural form and then in substance.

This brings us to the rulings handed down against members and leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood in cases involving charges of murder and incitement to murder, charges that in Egyptian criminal law can carry a penalty of life imprisonment or death. The case of Hisham Talaat Mustafa is relevant here.

The business magnate was a key official in the former National Democratic Party at the height of its power. Mustafa was arrested and charged with incitement to murder. His case has not yet been settled; he faces the prospect of capital punishment.

The same principle was applied in the recent verdicts against a group of Muslim Brotherhood leaders who were arraigned in various cities and governorates on charges of murder and incitement to murder following the breakup of the Rabaa Al-Adawiya sit-in in August 2013. Many innocent civilians were killed and many police officers murdered in the course of performing their duties at that time.

One cannot help but to be struck by the reactions to the verdicts. The verdicts were the result of legal and judicial procedures that are followed in any judiciary, and that ultimately lead to that step in which the judge, on the basis of all available proof and evidence, pronounces his verdict.

Instead of seeing those verdicts as proof of Muslim Brotherhood terrorism, critics used them, in a manner contrary to the principles of justice, to attack the process and the institution. It was, in fact, the critics who politicised the verdicts.

What measures and principles do the critics of those verdicts think have been applied? Perhaps they think that an eye-for-an-eye and a tooth-for-a-tooth should have been brought to bear against the Muslim Brothers and their allies who committed or incited the attacks against innocent people, the burning of more than 60 churches and the destruction of invaluable artefacts looted from antiquities museums.

The fact is that the appropriate measures were brought to bear in the framework of a more rational and impartial process, so that no one would suffer unduly. And, in fact, most of the defendants in the Al-Adwa Police Station case were acquitted. That case took place in Minya, where churches were burned, the homes of Christians attacked and burned, and many people killed. Those who were proven to have been involved in those incidents on the basis of the evidence were found guilty.

This brings us to a number of crucial questions. Did the judiciary depart from its normal rules and procedures, or did it apply the text of the law? Did it attempt to avenge those who were murdered and whose homes were burned? Did the court’s verdict serve as a deterrent to religious bigots whose hatred and intolerance of the other drives them to murder and burn homes in the name of religion?

At another level, was it the fact that the procedures of justice were applied at all that bothered critics abroad? Consider, for example, that they did not even take the trouble, before the verdicts were pronounced, to send specialists to study the background behind those many death sentences and to ascertain whether or not the crimes took place. Instead, the foreign ministers of the UK and other countries found it more convenient to comment on the verdicts without being fully informed.

To those people, I would like to ask whether it has somehow become part of the concept of freedom and democracy to not respect the process of law, even if the process has flaws that can be rectified by peaceful means. Have freedom and democracy extended to accepting the culture that assumes the right to oppose the state and its laws?

Would such attitudes be tolerated in your societies where the law is applied very strictly against those who break the rules? Yes, the death sentences when passed collectively may reflect a certain alarm or hysteria. However, have you ever seen someone slaughtered by a gang of hundreds? When was the last time you saw a pack of murderers mutilate the corpse of one of their victims? If the crime was committed en masse, why do you condemn the punishment of its perpetrators en masse?

The files of these cases, from their investigatory procedures to their documented evidence and their reasoned verdicts, do not only testify to the gravity of those crimes. They also testify to the crimes behind which the Muslim Brotherhood has lurked for 80 years.

These crimes include the killing of innocent people, the sowing of ignorance, the indoctrination of young and impressionable minds into a cult of blind obedience, and the inculcation of a culture of terrorism.

This culture has lead people to join the ranks of Islamist groups that have made it their mission to kill innocent people. Today, they are being recruited by new groups such as Ansar Beit Al-Maqdis, the Islamic State (IS) and like-minded entities for which murder is both the means and the end.

Comments Off on Justice and the Muslim Brotherhood trials

The fruit of hubris

November 19th, 2013By Azmi Ashour.

No one can have the lead role for good: this is the greater message of the ongoing Egyptian revolution, exemplified in the trial of Mohamed Morsi, writes Azmi Ashour

Egypt is not used to having former presidents, or former presidents on trial for that matter. But it is developing the taste.

Within less than three years, we managed to oust and then put on trial two presidents for very much the same set of offences.

Mohamed Morsi, a man who lasted in power for only one year, appeared in court on much the same charges that brought Hosni Mubarak, a man who stayed in office for 30 years, to justice before.

What this tells us is that Egyptian society, for all its deceptively simple appearance, is complex — though by now predictable — in its reactions.

Since the 25 January Revolution, this country has challenged a sequence of ruling elites, first bringing down the Mubarak coterie, then coming very close to defying the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) during the interim phase. The victory of the Islamists in parliamentary and presidential elections catapulted them to power, but their heavy-handed yet ineffectual policies triggered the widespread discontent that speeded up their ignominious demise.

In the first two years of the revolution, we grew accustomed to demonstrations and million-man marches. Still, no one saw coming the tumultuous wave of protests that ended Morsi’s rule.

Six months into the rule of Egypt’s first Islamist president, the writing was literally on the walls of his palace that were repeatedly surrounded by angry protests.

When the Tamarod movement managed to collect, within weeks, 22 million signatures demanding Morsi’s ouster, his fate was sealed.

On 30 June 2013, the nation took to the streets in force, led by an underestimated but indomitable middle class that had decided that enough was enough.

The scenes were familiar, but the numbers were unprecedented, and within days, Morsi — a man with limited ability to learn from the past — was in custody.

A new reality, one has to admit, was born in this country: a reality that is bigger than the political parties, stronger than the rulers, more alert than the elite, and yet resonant with the ideals of the revolution.

What this nation in more than one occasion made clear is that it wants true democracy, not the one that leads to monopoly by any political current. Politicians can rise and fall, but the ideals of the revolution will persist.

For a while, it seemed odd that SCAF would be demonised only a few months after it practically saved the 25 January Revolution. But even the most powerful army generals couldn’t outstay their welcome.

This was the lesson the Muslim Brotherhood failed to learn.

Their dismissive attitude, the haughtiness of their politics, and their holier-than-thou rhetoric antagonised the nation. And the cronyism that the Islamists quickly established, taken almost page for page from the book of the Mubarak regime, grated against public sensibilities.

A nation that has had enough didn’t grumble for long. In record time, it ended the rule of the Islamists.

This is a lesson to all. Political careers in this country can be made and unmade at an unprecedented rate. And even people who almost made it into office had their reputation shattered when they challenged the public mood. Mohamed Al-Baradei comes to mind, but he is not the only one.

The popularity of any given public figure, it seems, lasts only as long as he reflects the nation’s disposition. We had our share of popular faces at the onset of the revolution; then they receded into oblivion within months, or even weeks. The Ultras grabbed the headlines for a while, then the Black Bloc, and even the mighty Tamarod is now a shadow of its former self.

Such is the vitality of the revolutionary movement. Just as in an orchestra a performer cannot be allowed to improvise in the middle of a symphony, this nation is not allowing anyone to challenge its newly-found confidence.

This is the new law of this revolution: no one stays on top forever. No one can have the lead role for good.

This revolution is not about individuals, but about the whole nation, and all those ideals for which many young lives were cut short.

SCAF belatedly got the message, and just in time as it turned out. But its Muslim Brotherhood successors were too complacent, or perhaps thick headed, to see what was going on.

The current set of rulers is put on notice too. Today’s leaders must have the foresight to accommodate the new dynamic in this country.

No public figure is sacred; only the ideals of the revolution are. This is what the trial of Morsi is all about.

When Morsi and his top aides stood in the dock on 4 November 2013, theirs was not just a tragic case. Their sad reality wasn’t just the bitter fruit of hubris. It is evidence that this nation cannot be hoodwinked anymore.

The writer is managing editor of the quarterly journal Al-Demoqrateya published by Al-Ahram.

A new type of tyranny

September 19th, 2013

By Azmi Ashour.

One of the tragedies of our time is that millions of people can turn into refugees within the span of weeks, if not days. Suddenly, people who had homes and jobs and cars, friends and things to share and enjoy, are left without abode. Brutally robbed of dignity, financially strapped, they are left stranded, reliant on the reluctant mercy of others.

For years, we have been desensitised to the question of refugees. The Palestinians were there, all around us, but they were almost an invisible anomaly, a historical aberration attributed to high international intrigue. Their fate was not going to be joined by others, or that’s what we thought — until now.

From Syria to Iraq, and let’s not forget Sudan, people are being driven from their homes in droves. City people have been driven from their urban surroundings, country people from their rural milieu, and border town inhabitants were hemmed in, erratically pushed in either direction.

What is happening to us?

The easy answer is war. Throughout history, war and famine were the main instigators of mass human displacement.But in our case, there is something else. Our history of tyranny, I believe, is responsible for the current explosion of the refugee problem.

The despots of our recent past followed racist and sectarian policies that favoured some minorities over others, and turned some against the majority — as was the case in Syria and Iraq.

Once the dictatorships were overthrown, or seriously challenged, a Pandora’s Box of horror was unleashed upon us, with retribution inviting retaliation, and injustices morphing into bloodshed.

The Arab revolutions brought much of this upon us.

Despite their lofty ideas and their declared commitment to equality among all citizens, when the revolutions misfired — as was the case in Syria — the consequences for the population were unspeakable.

In the past two years, nearly two million Syrians, many rendered penniless overnight, had to flee into neighbouring countries. Of those who stayed behind, nearly 100,000 were killed and just as many perhaps went missing.

The Syrian crisis is now approaching the volume of the Palestinian crisis, with the added advantage of being fully home-grown.

Egypt and Tunisia were spared the worst, but only just — and only so far.The root of trouble in the Arab world is despotism.In Egypt, Sudan, Syria, Iraq and other countries, dictators were in power — some more brutal than others.

In Egypt, the dictatorship of the state was alleviated by the power of state institutions and the rule of the law. The regime may have been heavy-handed at times, but it wasn’t an inherently sectarian one.

In Sudan, sectarianism was paramount, and the institutions of central government were much weaker. Khartoum was clearly incapable of addressing the problems in the distant areas of Darfur and southern Sudan, and when challenged it resorted to bloodshed.

In Iraq, Saddam Hussein largely ignored the demands of various ethnicities and sects, but his police state created a tradition of brutality that came in handy when the country started falling apart.

The new cohort of leaders in Baghdad doesn’t seem capable of rising above the web of sectarianism that has grown unchecked over the past few years, to the detriment of the authority of the central government.

In Syria, the police state of the Baath Party, handed from father to son, lurked uncomfortably under the surface, and then broke loose into an orgy of violence once Bashar Al-Assad’s hold on power was challenged.

The Arab world may have overthrown the old cohort of dictators, but it hasn’t rid itself of their legacy.

In one country after another, a new batch of rulers is making the same mistakes that brought the downfall of its predecessors.

The Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, once it reached the top rung in the ladder of power, proceeded to reconfigure all state institutions to suit its own purposes, not those of the nation, its final aim being to install a minority of Islamists in power and make them the new overlords.

In Syria, Al-Assad took refuge in his Alawite clan, arming them against the rest of the population.

Such behaviour is not only essentially biased, but it poses a terrible threat to the entire country. For example, had the Muslim Brotherhood succeeded in turning the army around, thousands of years of tradition would have come asunder, and the very concept of a nation state would have been demolished.

Egypt is still struggling to find its footing. The 30 June Revolution is but another attempt to re-establish the concept of one country for all, without discrimination on ethnic or religious grounds.

We are still fighting. But instead of fighting against the tyranny of old-style regimes, we are fighting for freedom and equality under any current or future regime.

The writer is managing editor of the quarterly journal Al-Demoqrateya published by Al-Ahram.

Islamist clash with society

August 22nd, 2013

By Azmi Ashour.

In mediaeval Europe, the clash between the Church and the Enlightenment was one between the religious establishment and the new ideas and perceptions espoused by philosophers and theologians. The conflict only assumed a broader societal form with the elimination of the Church from the political realm and the gradual assimilation by society of Enlightenment thought. This evolution prepared the ground for the major revolutions of the 18th century that ushered in new systems of government. I speak here of the French and American revolutions, among the chief achievements of which was that they instituted political reforms that gave prevalence to such values as freedom and liberty and enshrined these principles — and guarantees for these principles — in their constitutions.

Comparing this to Arab societies, and the Egyptian case in particular, over the past two centuries, we find that reform came from the top. This applied from the era of Mohamed Ali in the first half of the 19th century through the Nasserist era in the 20th century, with some exceptions in the liberal era in which the soil was prepared for reform by an elite that had the positive effect on society of fostering the growth of an educated class that espoused modernist and democratic ideas.

In tandem with the political and social reform movement, the phenomenon of political Islam arose with the birth of the Muslim Brotherhood, founded by Hassan Al-Banna in 1928. Although his ideas conflicted with contemporary thought, he succeeded in building a social base using the religious factor, which easily served to recruit new classes into his ranks and to keep them in line.

The Muslim Brotherhood, thus, applied a top-down attitude towards society that was essentially an extension of its internal line-of-command structure in which inviolable and unquestionable instructions radiate downward through the echelons of a rigid hierarchy, as in any authoritarian order. Perhaps this is one of the main reasons why this organisation would never be able to generate an ideological system along the lines of that bequeathed by the Enlightenment, even though the ideas and values of the Enlightenment — such as freedom, justice, equality and tolerance — emanate from the very essence of Islam. It is also one of the factors that would lead this organisation to up the stakes in its contest with political authorities over a single aim, which was to come to power and gain hegemony over society at large. It is therefore not surprising that during its more than 80-year history the Muslim Brotherhood would lock horns in a fierce battle with a succession of heads-of-state, even as it continued to extend its presence among society drawing on a shared hatred for the regime and the Egyptians’ general vulnerability to religious exploitation.

However, after the 25 January Revolution toppled the conventional ruling authority by means of a peaceful uprising, the Islamists succeeded in attaining the power that had remained inaccessible to them due to the former regime’s monopoly over it. Yet, in view of their ideological and organisational makeup, it was not odd that, even though they came to power through a fair democratic poll, they would turn out to be more authoritarian than the rulers that preceded them. This reality precipitated major transformation in the Egyptian revolution, effectively abbreviating the centuries it took in the Western experience to shift the conflict with religious authority — as represented by Muslim Brotherhood rule — from the intelligentsia to society at large. The Egyptian public did not elect the Muslim Brotherhood to reproduce an authoritarian regime, but rather to realise the aims and aspirations of a revolution that had broken many taboos.

This dramatic transformation began to play out on the ground following the constitutional declaration of November 2012. That dictatorial declaration alerted the people to the immanent danger of the rebirth of a tyrannical order in a religious cloak and they arose in massive numbers to protest Muslim Brotherhood autocracy. Over the following six months, tensions gradually heightened in the face of the Muslim Brotherhood’s relentless intransigence until, finally, on 30 June, one year into the Mohamed Morsi presidency, unprecedented millions took to the streets and squares of Egypt to demand the end of Muslim Brotherhood rule. Indeed, a tangible sign of the extent to which modern democratic thought had spread among society was to be found in the petition drive that paved the way to that historic day and that had gathered more than 22 million signatures on a document declaring dissatisfaction with the current government and its Muslim Brotherhood masters. The 30 June movement culminated with the army intervention that brought president Morsi’s dismissal.

This transformation in the conflict on the ground is remarkable, if relatively late, for a traditional Arab society in which political and religious authoritarianism prevailed for more than 1,500 years. That society at large has taken up the struggle against the advocates of the ideas of radical Islamism without abandoning the strength of its religious faith as practiced in a modern way, reflecting contemporary ideas and values, will remain the most significant development in the Egyptian revolution.

In the past, Egypt saw the fall of a political order when Mameluk rule passed to Mohamed Ali. It experienced another transformation, from within the Mohamed Ali dynasty itself, following the 1919 Revolution that created a constitutional monarchy that presided over a rich period of liberal rule. Then came the order established by the Free Officers movement following the June 1952 Revolution. What is new today is that society itself is waging a revolution against traditional ideas and values which may be a basic reason for the gulf between us and other societies that created a renaissance for their peoples, a renaissance that did not eliminate the faiths of their peoples and, in fact, increased respect for these faiths.

The writer is managing editor of the quarterly journal Al-Demoqrateya published by Al-Ahram.