By Azmi Ashour.

Ever since political Islam reared its head in 1928, the year in which the Muslim Brotherhood was created, it has offered more impediments to society than hope.

Its lack of substance didn’t prevent it, however, from gaining recruits. And although at heart it constantly clashed with every concept of modernity and civil standards, it aspired to govern and strove to gain power.

Political Islam was never about governing one country, for at its core it aspires to universal supremacy. Strictly speaking, any nation that succumbs to political Islam, the proponents of such ideology believe, must be used as a stepping stone to acquiring more land and bringing more people under its wing.

The idea of ustaziyat al-alam, or global moral leadership, as put forward by Muslim Brotherhood founder Hassan Al-Banna, is rather baffling. According to this notion, Muslim Brotherhood members must offer themselves as role models for the entire world. And yet, the fundamental leanings of this group seem to run in the face of everything most of humanity agrees is common decency.

That this group harbouring so much animosity towards all modern values of the world should sees itself as a global saviour is quite intriguing. And yet various strands of the political Islam that the Muslim Brotherhood propagated still act as if they are entitled to world domination by dint of what they believe is a morally superior past.

From its outset, the Muslim Brotherhood developed a knack for assassinations. Opponents as well as top statesmen were mowed down by its armed outfits. And the spiral of radicalism this group started is still spawning horror to this day. Since the 1970s, splinter groups from the Muslim Brotherhood embraced increasingly radicalised notions of religion, lifestyle, and government.

The political Islam groups of the 1970s, operating still in Egypt, assassinated a minister of religious endowments, or awqaf, and then killed President Anwar Al-Sadat — a man who ironically relied on the Islamists to undermine his leftist opponents.

The wave of violence that these groups initiated continued unabated throughout the 1980s and 1990s.

When the Soviets invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the stage was set for another wave of political Islam, one that was more radicalised than the one before. As many young men left their countries to join the jihad against the Soviets, the war in Afghanistan offered them opportunities that were lacking in their own countries.

The veterans of the Afghanistan war brought extremist ideas not only to Egypt but also to most Arab countries. And a new generation of jihadists appeared across the region, where tyrannical regimes held on to power but offered no hope for true progress.

As the 20th century drew to a close, Al-Qaeda had already branched out in various Arab countries. Sudan in particular became a playground for Al-Qaeda operatives. And Algeria was subjected to a particularly bloody challenge from radical Islamists.

Then 9/11 sent the world into shock, triggering another wave of radicalism, one that was played out on a much larger scale, and with increasing brutality. As the Americans sent troops to occupy Afghanistan and Iraq, the jihadists gained momentum. The collapse of central government in Iraq was a bonus to radical groups that had no chance of challenging the watertight police state that had been in control of that country for decades. The rebirth of Al-Qaeda in Iraq was instantaneous and so far irreversible.

Iraq was disfigured by the occupation, and before long the country was torn apart by competing local and regional powers. Ethnic rivalry, religious sectarianism, and the special interests of countries such as Iran and Saudi Arabia weren’t conducive to Iraq’s unity or stability. And in the maze of shifting loyalties, radical Islam flourished.

The next wave was to be even worse. The Arab Spring, born in hope, ended up in disappointment as in one country after another. As the tyrants fell, the Islamists sprang into action.

No longer deterred by the police states of the past, the Islamists hijacked the revolution in both Egypt and Syria, alternately by ballots and bullets.

In both Egypt and Tunisia, Islamists managed to win elections but had trouble delivering on the promise of the revolution, having no use for the democracy and freedom that was supposed to follow the overthrow of authoritarian regimes.

As the Muslim Brotherhood rose to power in Egypt it developed a knack for intimidating its opponents. Not satisfied with controlling the government, the group had its radical allies bully judges and journalists. The sieges on Media City and the High Constitutional Court that followed were prolonged, and the Brotherhood encouraged rather than curbed this challenge to the country’s civil institutions. For the entire year the Muslim Brotherhood remained in office it treated with disdain the very institutions of the state it was supposed to protect.

By 30 June 2013, the people had had enough and they came out in numbers to demand the army intervention that ousted the Muslim Brotherhood from power.

One can only wonder what would have happened had the army not intervened. Just before being removed from office, President Mohamed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood urged a jihad in Syria — a move that could have only strengthened the hand of militant Islam back home.

The Islamists saw their chance and took it. But this is not to say that Arab societies are not to blame. The fertile soil for extremism is not confined to one Arab country, but exists throughout the region. The failure of tyrannical regimes to meet the expectations of their people furnishes the basis for discontent that the Islamists have grown adept at exploiting.

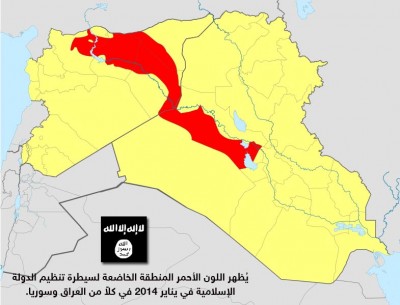

The emergence of the Islamic State, perhaps the ultimate form of disfigured militancy that political Islam has ever created, is proof that the political vacuum in both Syria and Iraq was complete. The fall of Saddam and the rapid erosion of Al-Assad’s power paved the way to radicalism on an unprecedented scale.

Many had assumed that the power vacuum left by the demise of tyrants would open windows for freedom. But events in Iraq, Syria, and elsewhere proved the opposite to be true.

The jihadists rose high in Syria and Iraq, but they were denied Egypt, their most coveted objective. In both Syria and Iraq, the radicals won ground only after the collapse of central power.

In Egypt, they are still trying to bomb and intimidate, although the country managed to keep its central power intact. Such is the desire to control Egypt, and such is the despondence at its loss, that the radicals are still fighting what until a few years ago would have been considered a hopeless battle.

This shows how determined the radicals are. They may be short on substance when it comes to common sense and compassion, but they are not short of support.

There are 3,000 Tunisian, 2,500 Saudi, and 2,000 Jordanian jihadists currently fighting under the Islamic State banner, according to available estimates.

Until recently, measures to stop the flow of combatants to war zones have been lax and clerics failed to denounce Islamic State crimes. This is changing as time goes by. But the fact is that the Islamic State used the same militant ideology that three generations of political Islam have used before it. The fault with political Islam is not confined to the Islamic State, for the twisted ideas have been around for decades, and so has the fertile soil of discontent.