Posts by JosepColomer:

Memories of Berlin, Before and After the Wall

November 6th, 2014By Josep Colomer.

On the 25th anniversary of the fall

1985

The metro from West Berlin crosses without stopping several underground stations in the eastern part, all bricked up and each with an East German soldier stationed in utter solitude and gloom, who is supposed to prevent against possible attempts of boarding the train by fugitives. At the border control, still underground and between large bars, the guard examining my Spanish passport gives me a tirade about the heroes of the International Brigades in the Civil War, which I guess I’m supposed to admire.

When I surface to the spacious Friedrichstrasse, I suddenly feel to have travelled a century back. A vast silence, very few people walking down the streets, almost no vehicles, no advertising on the facades. Only a few slogans hang from ledges of large buildings with wishes of long life to communism, marxism-leninism and the GDR (German Democratic Republic). There is a forbidden to step area on the outskirts of the Brandenburg Gate. At Alexanderplatz, in front the huge iron and glass building of the Palace of the Republic, I hear three men speaking Spanish and I dare to ask them how I could ascend to the communications tower; two of them turn out to be Cubans, as I suppose it was logical to imagine, but they immediately step back and let the other, blond and taller, who is clearly their supervisor and guide, to inquire me about my intentions. A few streets away from the large blocks of flats on Stalin Allee, which pretend to be standards of the socialist modernization of the sixties, emerge the typical dirt, poverty and dilapidated houses that seem substantial to the countries of real socialism.

Further away still, all the world records of air pollution are beat due to chemical plants and the use of the worst kind of lignite one could find in Europe, with which a planned but still savage industrialization has been boosted. At the monument to the victims of fascism and militarism, soldiers stand guard by alternating rigid immobility with ceremonial Prussian goose steps. While waiting for the tramway at the suburbs, I talk to a group of young people whose faces of despair far exceed those of the punks and subsidized artists of the western Kreuzberg who boast of “no future”; these don’t even have drug evasion available and they don’t even reach to turn their sarcasm into humor.

I cross back the wall on foot through the Checkpoint Charlie, where guards located above the watchtowers urge me with gestures and shouting to hurry up. At the first corner in the western part is the museum of the wall, which continues adding brutal images of eastern fugitives via tunneling, by jumping from windows to a canvas, flying in inflatable balloons, navigating by homemade submarines, or by racing in rudimentarily armored cars.

1989

There is a real boulder industry around the Berlin Wall. Groups of Germans and Turks, transformed into woodpeckers with escarpment and hammer, are draining the mason resources of the western facade. For four or five marks any tourist can buy a bag with a dozen pieces of painted concrete and an authenticity “zertifikat”. The processing of the souvenirs begins inside the western wall, until recently inaccessible because it faced an extensive no man’s land between two parallel strips of stone.

These stonecutters have proceeded to a careful distribution of the wall into numbered plots and industrious groups of workers have divided tasks: some daub with aerosolized buntings, mimicking the colors of the anti communist, hopeless or love graffiti that decorated the western side of the wall, others chop this newly colored stones, others pack boulders, and others ultimately bring the bags to the distribution stalls.

Not only is the wall that it’s sold at bargain prices in the western part of Berlin. Uniforms and hats of policemen and East German and Soviet soldiers, medals and military decorations of their commanders, brochures with speeches by communist bigwigs, manuals of marxism-leninism, copies of an official portrait of Soviet boss Brezhnev and East German Honecker heavily kissing each other on the mouth under their hats, flags with the coat with the workers’ hammer and the technological compass that replaces the Russian peasants’ sickle, that is, all objects that monopolized the image of the eastern part of Germany are being sold today in the streets like bargains in the process of extinction.

To the left and the right of the wall on closing-down sale, the picture is asymmetrical. On the one side, immigration of workers. On the other side, foreign capital investment.

It only takes to peek at Ku Damm –until now the stunning shopping center of the western part– to observe the massive presence of fugitives and visitors from the East. Poorly dressed and in re-concentrated expression of amazement before the luxurious and provocative windows full of jewelry, clothing and food, they walk with their carry bags or boxes and hold radios and video recorders that some will resale in the eastern part. The vast majority of young easterners seem to have thought that, as it read a banner at the demonstrations a few weeks ago, “Life is too short to spend it in the GDR.”

The Poles, whose border is only thirty miles from Berlin, are also particularly active in the trade. At Bernburgerstrasse, Turks and counterculture young people hold a daily outdoor market were the Polish try to sell trinkets, virgins of Czestochova and old furniture, in addition to contraband tobacco and alcohol, in order to collect federal marks and take with them oranges, coffee and electrical appliances, which are scarce in the eastern lands. Thousands of people cross every day the Oder Neisse border and twice the controls in East Berlin to pursue this task.

The other way around, the western private sector is tiring down barriers in the Eastern part. There is a new atmosphere of hustle and nonchalance in the streets. Plenty of American and European tourists stroll all over; groups of businessmen from the West, all with their wallet in hand and a distinctive aspect of well-fed people, run the streets quickly; along with the usual motion of modest Trabant cars of East residents, one can now easily go across a swanky Mercedes convertible with the radio full blast; groups of unemployed youth offer illegal currency exchange under the indifferent gaze of the police; children try to stretch the boot buckle of the occasional soldier and to touch his gun.

Dozens of commercial signage and illuminated advertising of companies from West Germany sparkle, while many shops have been opened on the ground floor. Siemens and Bosch live in walking distance to the Deutsche Bank, Hoechst and Volkswagen as visible expressions of the takeover bid of East Germany by western companies. Some commercial advertising campaigns also convey a political message.

The Struyvesant cigarettes use a slogan in English, “Come Together”, which appeared on the banners of festive assailants of the wall a few weeks ago. Another brand has flooded the city with billboards and vans with a simple and strong message, also in the international language: “Test the West”. Unified Berlin is going to become, again, the core of Germany, and a unified Germany may find itself at the core of Europe rather soon.

Comments Off on Memories of Berlin, Before and After the Wall

Who was the median voter in Brazil?

October 30th, 2014

By Josep Colomer.

The answer is: the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (Partido do Movimento Democrático Brasileiro, PMDB). Many people may not have heard much of this party recently because the party didn’t run a presidential candidate on its own. But, as always, it’s the median voter’s and the median seat party and the king-maker (that is, the president-maker). The opposite of the parliamentary kings, the PMDB doesn’t reign but it rules.

The crucial role of the PMDB is very clear in the parliamentary election, which is held by proportional representation. The PMDB obtained only 11 % of votes (66 seats), but, on its left, the direct supporters of the incumbent president Dilma Rousseff plus the far left received 47% of votes (238 seats), while the center and right parties received in total 42% of votes (209 seats), thus leaving, as usual, the PMDB in the pivotal position capable of making a majority on any of the two sides.

The PMDB is the continuator of the official opposition during the last years of the military dictatorship in the 1970s. In the first open presidential election in 1985, which was held by means of an electoral college, the PMDB candidate, Tancredo Neves, was chosen president, and at his early death was replaced by his running mate Jose Sarney from the same party. However, the PMDB has not run presidential candidates on its own in most direct presidential elections since the 1990s.

As typical of some anti-dictatorial parties, the PMDB is a catch-all party, which groups together a large range of politicians, coordinates diverse regional groups, and obtains the support of not very ideological voters. Today it is the Brazilian party with the largest number of affiliates.

It has elected higher numbers of governors, senators and deputies at state level than any of the other major parties in the last election. The PMDB has participated in most presidential cabinets with presidents of different parties. The current leader of the PMDB, Michel Temer, was a long-term chairman of the Chamber of Deputies and has most recently been vice-president of the republic with president Rousseff, with whom he ran for reelection a few days ago.

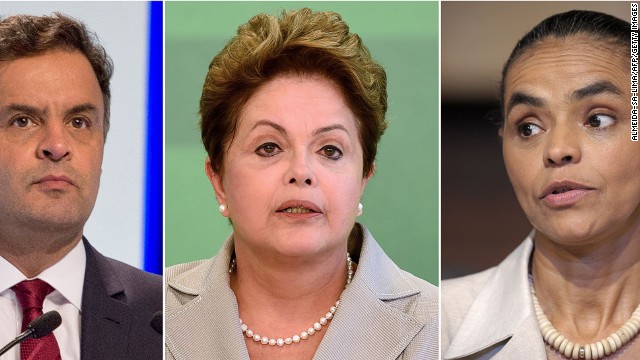

The crucial role of the PMDB in the recent presidential election may have been disguised. By looking at the three major candidates, Rousseff of the Workers’ Party (PT) on the left, Marina Silva of the Socialist Party (PSB) on the center-left, and Aécio Neves of the Social Democracy Party (PSDB) on the center-right, it may seem that Silva was the median voter’s candidate at the first round.

Actually some PMDB voters may have voted for Silva, and even a few for Neves (especially in the state of Rio Grande do Sul), at the first round. The vacillations of PMDB voters may be a major explanation for the survey polls that during a few weeks predicted that Silva would pass to the second round.

If this had happened, most likely Marina Silva would have been elected president of Brazil. But Neves’ stronger campaign placed him on second place. At the second round, as Silva had been eliminated, most PMDB voters chose Rousseff and their party’s vice-presidential candidate and made them the winners.

As usual, president Rousseff will need the support of a multiparty majority in Congress and, as usual too, the PMDB will be pivotal for attaining such a goal.

Comments Off on Who was the median voter in Brazil?

Can England Be a Federation?

September 30th, 2014

Can England Be a Federation?

After the referendum in Scotland and the awareness that the territorial distribution of power across the United Kingdom is not well settled, proposals have emerged to create an English parliament. However, England encompasses about 85% of the population of the UK, which would make a federal-type arrangement too asymmetrical and highly unlikely to be accepted by the Scots and survive. The problem looks similar to the one with Ireland in the past, which, after Irish independence, left the legacy of a long conflict and the current special status for Northern Ireland.

Many two-unit federations have failed as a consequence of the large group’s dominance and the small group’s choice of secession. Cases in modern times include the following: In America, after the early independence of four Vice-royalties from the Spanish empire: Argentina with the separation of Paraguay and Uruguay; Colombia with the separation of Ecuador, Venezuela, and later Panama; Peru with the split with Bolivia; Mexico with the separation of Guatemala and, immediately afterward, the rest of Central America in dispersion. In Asia and Africa, after independence from the British empire: India with separation by Pakistan; Pakistan with secession of territorially separated Bangladesh later on; South Africa with secession by Namibia; Rhodesia (which became today’s Zimbabwe) with secession by Zambia and Malawi; Ethiopia with secession by Eritrea; Sudan with secession of South Sudan. During the First World War, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Russian empire collapsed by self-determination of numerous previously dominated units. The successor of the latter, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, was initially a federation of only four remaining territories: Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Transcaucasia; after territorial expansion, it was organized into fifteen republics and numerous autonomies, regions, and areas, as well as officially recognized nationalities and ethnic groups, but Russia always contained more than 51 percent of total population and two thirds of the territory, which eventually led to its split into fifteen countries. In Eastern Europe, Czecho-Slovakia ended with secession of the latter; and the Serbian-dominated Yugoslavia split into seven republics.

In contrast to the frailty of two-unit, polarized federations, successful experiences usually encompass high numbers of units. With territorial pluralism, none of the units can reasonably feed its ambitions of becoming the single dominant one, thus leaving the small communities to develop their own ways within the union. The best examples of how a very large territory can be structured in a federal-like manner are the United States, with 50 units, and the European Union, with 28 states (and about 100 regional governments) so far. The challenge for the large United Kingdom is to adopt a sufficiently pluralistic structure, certainly preventing any unit from including more than 50% of total population.

Comments Off on Can England Be a Federation?

Why a so dis-United Kingdom

September 16th, 2014

By Josep Colomer.

This week there will be a referendum in Scotland about independence from the United Kingdom. Survey polls predict a tight, uncertain result. One can wonder how the United Kingdom has become so increasingly disunited.

In short: Too simple institutions and too much concentration of power have lead to polarization between the British central government and the Scottish government.

This was predicted quite a while ago.

From my book Political Institutions: Democracy and Social Choice(Oxford 2001):

“In the mid 18th century, the political regime of England was considered to be the best example of ‘one nation in the world that has for the direct end of its constitution political liberty’ founded on the principle of separation of powers (Montesquieu, 1748). In contrast, by the mid 20th century, political students widely agreed that the United Kingdom was ‘both the original and the best-known example’ of the model of democracy based on concentration of powers (see, for example, Lijphart 1984).”

How this evolution from wide institutional pluralism to high concentration of power took place?

“For some time after the union with Scotland in 1707, the central government in London respected Scottish autonomy, especially in matters of religion, private law, and the judiciary system. Britain was also highly decentralized in favor of local governments at least until the early 19th century.

“However, with the steady expansion of voting rights during the 19th and 20th centuries, the popularly elected House of Commons came to prevail over the nonelected King and House of Lords. But the Commons were elected by means of a highly restrictive electoral system based on plurality rule, typically producing a two-party system and single-party Cabinets. Thus, democratization implied increasing concentration of powers in the hands of a single-winning actor, the party in Cabinet, and, more precisely, the Premier. The regime was dubbed an ‘elective dictatorship’, in contrast with the previous model of limited government. Unification in national government caused increasing centralization. Whereas some traditional Scottish institutions were curbed, Ireland seceded before it could be dominated, in 1920. Later, violent conflict in Northern Ireland led to the suppression of the local Assembly by the central government in 1969. Local governments were weakened by the central government through the 1980s, including the abolition of the Greater London Council.

“Major institutional reforms in favor of reestablishing pluralism were only initiated at the initiative of those excluded from power during a long period without governmental alternation. When the Labourites went back in government, they promoted the corresponding institutional reforms… Regional Assemblies and governments were created in Scotland and Wales (the latter with no legislative or taxation powers) since 1999 …

“However, a few remarks are relevant.

“First, the absence of provisions for the establishment of regional governments across England might induce either unified government (if the national government party obtains a majority in the regions) or bipolarization between the central and the Scotland governments, rather than inter-regional cooperation.

“Second, although the House of Lords was deprived of most of its hereditary members, it was not replaced with a corresponding upper chamber of territorial representation, which also reduces the opportunities for multilateral exchanges.

“In short, the fate of the new vertical division of powers in the United Kingdom may depend on the further extension of decentralization to other regional units and the development of institutions of multiregional cooperation.”

ADD 2014: As nothing of this has happened, then, as predicted, polarization between the central government in London and the Scottish government has increased, up to the present point.

Comments Off on Why a so dis-United Kingdom

Josep Colomer answers questions about independent movements in Spain

September 8th, 2014

Interview by Lluis Amiguet.

Josep Colomer is a Professor of Political Science at Georgetown University

Comments Off on Josep Colomer answers questions about independent movements in Spain

80:20 Piketty disregards Pareto, Zipf

June 16th, 2014

By Josep Colomer.

Thomas Piketty’s best-selling Capital in the Twenty-First Century is rich and innovative in data, although the author’s management of some sources is now being discussed. Another matter is that his findings could be illuminated by previous work that he may have overlooked. Some light could possibly be cast over the issue of wealth distribution, for instance, from the tradition of literature on “rank-size distributions”. According to the so-called “Zipf’s law” (for the American linguist George K. Zipf, who popularized the idea in the 1940s), remarkable regularities can be observed in the distribution of disparate resources, whether population in cities, frequency of word usage –and also wealth among individuals and groups, which is Piketty’s topic.

Zipf’s basic formula is:

Sk = S1/ks

which means that the size of the k-th unit in rank equals the size of the first unit divided by k (raised to power s). A simplified formula makes s=1, which would mean that in a population divided in groups of equal number of individuals the share of wealth in the hands of the second wealthiest group would be half the first, the share of the third group would be one third of the first, and so on. The higher the value of s, the more unequal the distribution; the formula can, thus, be adjusted for empirical data in order to fit the basic values and confirm (or not) a regularity.

Let’s assume that a certain population can be divided in ten deciles. Zipf’s cumulative distribution looks like the Figure above. The data presented by Piketty would fit the cumulative distribution derived from s=2 rather well. This means that the top 10 percent of the population would accumulate about 62 percent of total wealth. But even more interesting is that the top 20 percent would get about 81 percent.

The latter values are extremely close to those postulated by Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto, who observed in early 20th century that 20 percent of the population owned 80 percent of the land in Italy (and viceversa, of course: the remaining 80 percent of the population owned 20 percent of the land). Pareto’s “80:20 law”, which could be considered, in retrospect, a case of Zipf’s law, has been used to understand many phenomena. [For instance, as a personal aside, in working with a research team I noted that we had written 80 percent of a paper in a certain, relatively brief amount of time, but that to complete the remaining 20 percent (which required an apparently minor effort at searching for a few new data, filling gaps, drawing Tables and Figures, footnoting, referencing, and above all, solving a few disagreements) was taking much longer].

Piketty’s main point is that the distribution of wealth in a few most developed countries has become more unequal in the last twenty years. But his data show that it’s still significantly less unequal than it was one hundred years ago, when Pareto presented his findings on the distribution of income and wealth among the population. Piketty does not mention Zipf and discusses only the so-called Pareto’s coefficients to compare the income of different fractions of the population, but he doesn’t mention the 80:20 law.

Comments Off on 80:20 Piketty disregards Pareto, Zipf

To the new King of Spain: Do like in Italy

June 4th, 2014

By Josep Colomer.

The abdication of King Juan Carlos has been compared with those of the Queen of the Netherlands and the King of Belgium last year. But the new King Philip VI could take more inspiration from the Head of State of Italy. The Italian Republic is a parliamentary regime, in which the Head of State has ceremonial powers, such as in Spain, but not only. Like the Italian Constitution, and like the great majority of those in European parliamentary systems, the Spanish constitution states that the Head of State must also arbitrate and moderate the regular functioning of the institutions. This task has been greatly missed in Spain in recent years, when the Parliament, the Government and the Judiciary stopped functioning in accordance with their constitutional missions. Now is the time when the new Head of State could use its powers to facilitate a new wave of recovery and renewal.

The Italian President, Giorgio Napolitano, has been an example of courage, skill, sense of duty and good service to citizens, from which the Spaniards could derive much benefit. Two and a half years ago the Italian government, buffeted by a series of scandals and the prosecution of its leader, was paralyzed in front the country’s economic crisis and pressures from the European Union.

The Head of State then removed the Prime Minister and appointed in his place a highly reputed independent professional with experience in prestigious European institutions, who formed a government with the best specialists in each field, without a single member of any political party, but won nevertheless the support of 90 percent of Parliament. The new government was also supported by the leaders of the European Union and the United States. Italy has since had its best period of government in modern history.

According to the electoral timetable, a new election was called after a year and a half (more or less the same time remaining now in Spain to the deadline for a new call). Following that election, resistance to change by the traditional political parties made it impossible the formation of a parliamentary majority, which would have required a grand coalition with members of the two major parties. But this was formed a few months later, at the cost of a shake-up of the party system

Meanwhile, President Napolitano had appointed a committee to develop public policy proposals formed by ten experts, some of which became part of the new government. It is quite remarkable that all this experience took place in a country that was known as a “party-cracy”, ie, by a degree of control of party leaderships on public institutions equal or even higher than usually reported in Spain. The biggest advantage of an initiative of the Head of State is that it comes from outside the political parties, so it can be especially effective in inducing reforms that also affect the party system.

As a result of that process, the current Italian Prime Minister, Matteo Renzi, heads a Cabinet of independent experts and members of the parties of the cente-right and the center-left, which, among other results, has confirmed the removal of Italy from the European Commission’s list of Southern European countries placed under the Excessive Deficit Procedure. His party has obtained the best result of all governmental parties in Europe in the recent election to the European Parliament, which may suggest that economic restructuring and legislative reforms may also accompany new policy normalization.

According to the Spanish Constitution, the Head of State may dismiss the Prime Minister, dissolve parliament, call elections, appoint a new Prime Minister, as well as the ministers proposed by the latter, personally chair meetings of the Council of Ministers, issue governmental decrees, promulgate laws and, according to the Prime Minister appointed by him, call referendums on political decisions of special importance. It is generally expected that the Head of State use these capabilities according to the election results. But in an emergency situation –as is undoubtedly the Spanish– the powers of the Head of State are to be used, as in the Italian case, according to the letter of the constitution.

Although not required by the constitution, and if only for ceremonial courtesy, the current Prime Minister should put its resignation to the new King. The formation of a government of broad multiparty coalition, a new agreement with Catalonia, sending signals of renewal and optimism to induce capitals in exile to return and to attract new foreign investments, could be the 23-F of King Philip VI [on 23-F 1981 King Juan Carlos stopped a military coup d’etat].

That is, his legitimation, not by dynastic or constitutional reasons, but by the results of his action. Like his father needed more than thirty years ago, the new Head of State will need a legitimation of this type by a large majority of Spanish society, as well as by the international scene, to consolidate his office in the years to come.

Comments Off on To the new King of Spain: Do like in Italy