By Syed Qamar Afzal Rizvi.

Unnerved by the fact that one of its leading “Monkeys”, in service senior Raw officer Kulbashan Yadav, has got into the hands of Pakistan, New Delhi is frustratingly trying to get consular access which it had never demanded before in any other case. ‘Capture of spy proves Indian interference in Pakistan: Army’ said Dawn, Pakistan’s most sober newspaper – its headline departing from the rest by attributing the information about Jadhav (and the assessment of his ‘confession’) to the army. The newspaper quoted the military spokesman as saying Jadhav’s confession “is solid proof of Indian state-sponsored terrorism”. The article reveals that the captured India will be ‘prosecuted as per the law of the land’ and decisions regarding consular access for Indian authorities will be taken at a later date.

While Pakistani security agencies are preparing a strong case to expose India’s state-sponsored terrorism against Pakistan and there are hints of something more to unfold in the days to come, Indian propaganda machinery is frustratingly asking for consular access of Kulbashan Yadav aka Mubarak Hussain Patel. In response to Indian demand, Pakistani security agencies sources offer, “ India will have to accept, first, all the crimes of Kulbashan only then Pakistan will consider to exercise its discretion in granting the consular access or otherwise.”

Espionage & international law

The core of espionage is treachery and deceit. The core of international law is decency and common humanity. This alone suggests espionage and international law cannot be reconciled in a complete synthesis.

Espionage is curiously ill-defined under international law, even though all developed nations, as well as many lesser-developed ones, conduct spying and eavesdropping operations against their neighbors.’ Examined in light of the realist approach to international relations, states spy on one another according to their relative power positions in order to achieve self-interested goals. This theoretical approach, however, not only fails to explain international tolerance for espionage, but also inadequately captures the cooperative benefits that accrue to all international states as a result of espionage. Although no international agreement affirmatively endorses espionage, states do not reject it as a violation of international law.’

As a result of its historical acceptance, espionage’s legal validity may be grounded in the recognition that “custom” serves as an authoritative source of international law. Espionage is a crime under the legal code of many nations.

In the United States it is covered by the Espionage Act of 1917. The risks of espionage vary. A spy breaking the host country’s laws may be deported, imprisoned, or even executed.

The Third Amendment Amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan is an amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan went effective on 18 February 1975, under the Government of elected Prime ministrer Zulfikar Ali Bhutto an amendment to the 1973 Constitution of Pakistan. The amendment extend the period of preventive detention, of those who are accused of committing serious cases of treason and espionage against the state of Pakistan, are also under trial by the government of Pakistan.

A spy breaking his/her own country’s laws can be imprisoned for espionage or/and treason (which in the USA and some other jurisdictions can only occur if he or she take ups arms or aids the enemy against his or her own country during wartime), or even executed, as the Rosenbergs were. For example, when Aldrich Ames handed a stack of dossiers of U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) agents in the Eastern Bloc to his KGB-officer “handler”, the KGB “rolled up” several networks, and at least ten people were secretly shot. When Ames was arrested by the U.S.

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), he faced life in prison; his contact, who had diplomatic immunity, was declared persona non grata and taken to the airport. Ames’s wife was threatened with life imprisonment if her husband did not cooperate; he did, and she was given a five-year sentence. Hugh Francis Redmond, a CIA officer in China, spent nineteen years in a Chinese prison for espionage—and died there—as he was operating without diplomatic cover and immunity.

International humanitarian law and its application

According to Article 29 of customary International Humanitarian Law, “A person can only be considered a spy when, acting clandestinely or on false pretences, he obtains or endeavours to obtain information in the zone of operations of a belligerent with the intention of communicating it to the hostile party.” If Pakistan can sufficiently establish through proof that the Yadav is a spy then his rights for consular access are automatically forfeited. No country has the right to treat unlawful combatants or spies inhumanely.

Article 30 of the same law states, “A spy taken in the act shall not be punished without previous trial.” India and Pakistan have been trying spies in military courts. The sentences have been rarely challenged in the Supreme Court. More recently, India has been exerting civil society pressure on the pretext of humanitarian grounds. In one case, an attempt was made to shield a convicted spy as a case of mistaken identity.

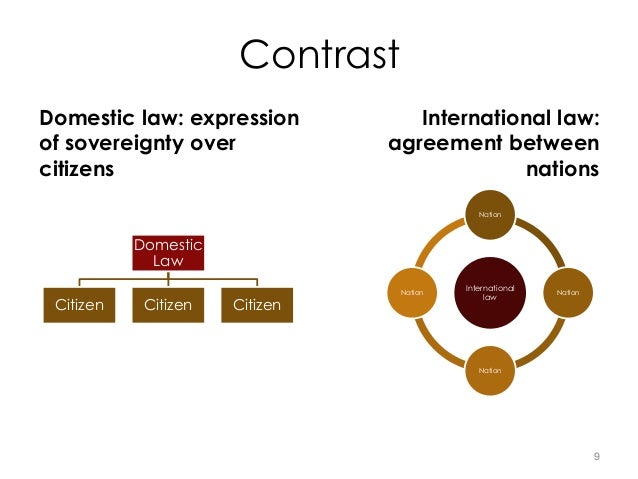

Sovereignty & international law

Sovereignty is a core precept of public international law, guarding a state’s essentially exclusive jurisdiction over its own territory. A concomitant principle is that “[e]very State has the duty to refrain from intervention in the internal or external affairs of any other State” and “the duty to refrain from fomenting civil strife in the territory of another State, and to prevent the organization within its territory of activities calculated to foment such civil strife.”

The principle of non-interference in sovereign affairs is recognized most famously in the U.N. Charter itself, which provides in Article 2(4) that “[a]ll Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.” The principle is, however, broader than this preoccupation with use of force suggests.

As the influential General Assembly Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Co-operation Among States in Accordance with the Charter of the United Nations declares, “[e]very State has an inalienable right to choose its political, economic, social and cultural systems, without interference in any form by another State” and “[n]o State or group of States has the right to intervene, directly or indirectly, for any reason whatever, in the internal or external affairs of any other State.” While not itself a source of public international law, the Declaration is almost certainly a reflection of current customary international law.

The Indian case

There are undoubted examples of espionage – broadly defined to include, e.g., covert military assistance – that exceed the non-interference standard. In the case of Yadav, Islamabad is unlikely to budge given the ‘evidence’ of Indian support for terrorism in Balochistan and Karachi, which adds up in the statement of Premier Modi in Bangladesh of severing East Pakistan and then by those of his defense minister Manohar Parrikar and Ajit Doval, advisor on national security.

The exercise of what is known as “enforcement jurisdiction” by one state and its agents in the territory of another is clearly a breach of international law – it is impermissible for one state to exercise its power on the territory of another, absent consent or some other permissive rule of international law. Keeping this yardstick in mind, It appears that Indian spying over Pakistani territory is in gross violation of international law.

Pakistan is collecting evidence to prove India is a direct sponsor of terrorism. The fact of the matter is that if the confession- made by Yadav- indulges his activities in promoting Indian sponsored state terrorism against Pakistan,there is much likelihood that the case may take a grave turn.

The UN’s role may be a significant step in this case. Pakistan has already submitted to the UN officials the dossier regarding Indian terrorist involvement in Pakistan. Now,with the rising of Yadav’s case, Islamabad may hold the expectations that the UNSC should refer the case to the International Criminal Court(ICC).

“We have briefed the P5 (the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council) and the European Union on the issue,” Zakaria,Pakistan’s Foreign Office Spokesperson said. He added that Yadav’s revelations had vindicated Islamabad’s position and exposed India’s designs against Pakistan.