By Syed Qamar Afzal Rizvi.

Pakistan upholds the right of the people of Jammu and Kashmir to self-determination in accordance with the resolutions of the United Nations Security Council. These resolutions of 1948 and 1949 provide for the holding of a free and impartial plebiscite for the determination of the future of the state by the people of Jammu and Kashmir. Pakistan continues to adhere to the UN resolutions. These resolutions are yet binding on India.

The UN’s mediatory role

The United Nations was involved in the conflict between Pakistan and India just months after the partition of British India. India brought the issue of Pakistani interference in Kashmir before the U.N. Security Council on January 1, 1948. Under article 35 of the U.N. charter, India alleged that Pakistan had assisted in the invasion of Kashmir by providing military equipment, training and supplies to the Pathan warriors. In response, Pakistan accused India of involvement in the massacres of Muslims in Kashmir, and denied any participation in the invasion.

Pakistan also raised question about the validity of the Maharaja’s accession to India (ii), and requested that the Security Council appoint a commission to secure a cease-fire, ensure withdrawal of outside forces, and conduct a plebiscite to determine Kashmir’s future (iii). The Security Council adopted a resolution establishing the United Nations Commission on India and Pakistan (UNCIP), to act as the mediating influence, and to undertake fact finding missions under article 34 of the Charter (iv). Shortly thereafter, the Security Council adopted another resolution in support of Kashmir’s right to self-determination, and in recognition for the need for a plebiscite (v). The plebiscite would be conducted under the supervision of an administrator appointed by the U.N. Secretary General and certified by UNCIP.

The resolution also called for withdrawal of armed Pakistani tribesmen and instructed India to reduce her forces. The Commission was informed that both countries had made the situation very complicated as Pakistani regular troops were already inside the borders of Kashmir and that the tribal invasion plus the Indian intervention had evolved into a larger state of war between India and Pakistan.

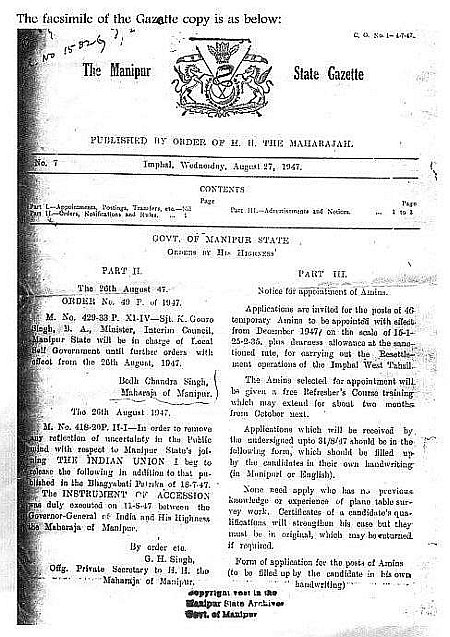

What about the instrument of accession?

A detailed examination into the legal order endorses the fact that India’s claim to Kashmir appears inconsistent with international law. Certainly, one may seriously question the Maharaja’s authority to sign the Instrument of Accession.

Pakistan argues that the prevailing international practice on recognition of state governments is based on the following three factors: first, the government’s actual control of the territory; second, the government’s enjoyment of the support and obedience of the majority of the population; third, the government’s ability to stake the claim that it has a reasonable expectation of staying in power.

The situation on the ground demonstrates that the Maharaja was hardly in control of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. In fact, almost all of Kashmir was under the control of the invading tribesmen and local rebels. The Maharaja held actual control over only parts of Jammu and Ladakh at the time that the treaty was signed. Moreover, Hari Singh was in flight from the state capital, Srinigar.

With regard to the Maharaja’s control over the local population, it is clear that he enjoyed no such control or support. Furthermore, the state’s armed forces were in total disarray after being thoroughly defeated by the invading forces and the local uprising. Finally, it is highly doubtful that the Maharaja could claim that his government had a reasonable chance of staying in power without Indian military intervention.

This assumption is substantiated by the Maharaja’s letter to the Government of India, in which he states that, “if my state has to be saved, immediate assistance must be available at Srinigar.” Therefore, if the Maharaja had no authority to sign the treaty, the Instrument of Accession can be considered without legal standing.

The legality of the Instrument of Accession may also be questioned on grounds that it was obtained under coercion. The International Court of Justice has stated that there “can be little doubt, as is implied in the Charter of the United Nations and recognized in Article 52 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, that under contemporary international law an agreement concluded under the threat or use of force is void.” As already stated, India’s military intervention in Kashmir was provisional upon the Maharaja’s signing of the Instrument of Accession. More importantly, however, the evidence suggests that Indian troops were pouring into Srinigar even before the Maharaja had signed the treaty. This fact would suggest that the treaty was signed under duress.

Finally, there is some doubt as to whether the treaty was ever signed. International law clearly states that every treaty entered into by a member of the United Nations must be registered with the Secretariat of the United Nations. The Instrument of Accession was neither presented to the United Nations nor to Pakistan.

While this does not void the treaty, it does mean that India cannot invoke the treaty before any organ of the United Nations. Moreover, further shedding doubt on the treaty’s validity, in 1995 Indian authorities claimed that the original copy of the treaty was either stolen or lost. Thus, an analysis of the circumstances surrounding the signing of the Instrument of Accession suggests that the accession of Kashmir to India was neither complete nor legal, as Delhi has vociferously contended for over fifty years. Kashmir may still legally be considered a disputed territory.

The core of the principle of self-determination

The principle of self-determination stipulates the right of every nation to be a sovereign territorial state. It affords to each population the right to choose which state it wishes to belong to, often by plebiscite. The principle of Self-Determination is commonly used to justify the aspirations of minority ethnic groups. The principle equally grants the right to reject sovereignty and join a larger multi-ethnic state. With regards to the Kashmir conflict, it is clear that Kashmir offered an ideological problem for both India and Pakistan. For Pakistan the Muslims of Kashmir had to be part of Pakistan under two nation theories (x), and for India, the failure of a Muslim majority state to survive within its system put under strain its secular vision. While considering the basic principle behind self-determination, as article 1(2) of the Charter of the United Nations 1945 states: ‘The purposes of the United Nations are…to develop friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples, and to take other appropriate measures to strengthen universal peace…’ we must also recognize that the doctrine of self-determination is also part of two more international human rights treaties: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (xi), and the International Covenant on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights (xii). Common article 1, paragraph 1 of these Covenants provides that: ‘All people have the rights of self-determination, by virtue of that right they freely determine their political states and freely determine their economic, social and cultural development.’

Pakistan’s argument

Pakistan argues that even if the Instrument of Accession is considered legal, India’s refusal to hold a plebiscite in Kashmir makes the accession incomplete. India, however, argues that its expressed “wish” to hold a plebiscite in Kashmir is amoral, not legal obligation. Pakistan, however, retorts that India’s obligation to hold a plebiscite in Kashmir arises out of India’s acceptance of the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan (UNCIP) resolutions of August 13, 1948.

This resolution contains proposals for holding a plebiscite in Kashmir which would allow the people to choose between accession to either Pakistan or to India. India asserts that the resolution states that the plebiscite will be held when a ceasefire is arranged and when Pakistan and India withdraw their troops from Kashmir. Neither of these conditions has been met.

But India’s position seems murky and dwindling considering the legal principle expressed in the Latin maxim nullus commodum capere potest de injuria sua propria (no man can take advantage of his own wrong). In the context of the Kashmir dispute, this means that India cannot frustrate attempts to create conditions ripe for a troop withdrawal and ceasefire in order to avoid carrying out its obligations to hold a plebiscite.

The evidence suggests that India was clearly at least as equally unwilling as Pakistan to withdraw troops from Kashmir. The London Economist stated that “the whole world can see that India, which claims the support of this majority [the Kashmiri people]…has been obstructing a holding of an internationally supervised plebis-cite.”

The Kashmir mediator’s findings

Owen Dixon, the United Nations Representative to the UNCIP, reported to the Security Council that, In the end, I became convinced that India’s agreement would never be obtained to demilitarization in any such form, or to provisions governing the period of the plebiscite of any such character, as would in my opinion permit the plebiscite being conducted in conditions sufficiently guarding against intimidation, and other forms of abuse by which the freedom and fairness of the plebiscite might be imperiled. In September 1950, Sir Owen Dixon, reported, that all means of settling the dispute over Kashmir, had been “exhausted” and suggested that India and Pakistan, be left to negotiate a settlement among themselves.

In this regard, India’s apparent efforts to obstruct the holding of a plebiscite in Kashmir stand in violation of international law. International law, however, clearly declares that states are obliged to treat all of their “peoples” equally and to insure that minorities are treated in a manner that does not threaten their culture or identity. Principle VII of the “Declaration on Principles” in the Helsinki Final Act pronounces that “the participating States on whose territories national minorities exist will respect the right of persons belonging to such minorities to equality before the law, will afford them the full opportunity for the actual enjoyment of Human Rights and fundamental freedoms and will, in this manner, protect their legitimate interests in this sphere.

The last attempt made by the UN

A legal solution based on arbitration was possible in 1957 when UNSC reaffirmed its earlier resolution that require the plebiscite. Gunnar Jarring was appointed by UN to mediator between India and Pakistan. On his proposal to demilitarization Pakistan Prime Minister Sir Feroz Khan Noon’s declared that his country was willing to withdraw its troops from Kashmir to meet India’s preconditions, the Security Council once again sent Frank Graham to the area. He tried to secure an agreement between India and Pakistan but India again rejected it. In March 1958, Graham submitted a report to the Security Council (UNSC) recommending that it arbitrates the dispute but as usual India rejected the proposal.

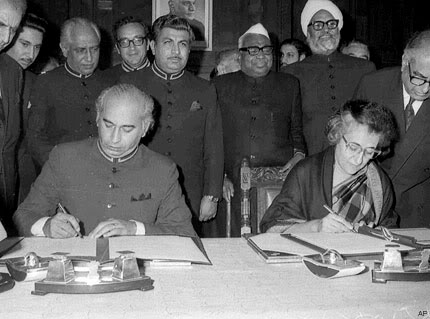

The notion of Simla agreement

The Simla Agreement does not prevent rising of Kashmir issue in the UN. It also does not restricts both countries for seeking the bilateral resolution only. Para 1 of Simla agreement specifically provides that the UN Charter “shall govern” relations between the parties. Para 1 (ii) providing for settlement of differences by peaceful means.

Articles 34 and 35 of the UN Charter specifically empower the Security Council to investigate any dispute independently or at the request of a member State. These provisions cannot be made subservient to any bilateral agreement.

According to Article 103 of UN Charter, member States obligations under the Charter primacy over obligations under a bilateral agreement. Presence of United Nations Military Observes Group in India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) at the Line of Control in Kashmir is a clear evidence of UN’s involvement in the Kashmir issue.

India’s legal & moral responsibility

As a party to both the Geneva Convention and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, India is obliged to follow standards of human rights enshrined in these treaties. Pakistan declares that India has committed gross violations of human rights in Kashmir, thereby violating international law and justifying Kashmir’s right to self-determination. Those Indian thinkers or policy engineers who think that the principle of self determination of the people of Kashmir comes outside the colonial context and has no justification for UN’s mandatory role in Kashmir are absolutely in line up with the Israeli policy thinkers who also argue that Israel’s today enjoys the leverage of the doctrine of uti possidetis juris (0f 1810).They both are wrong and delusional in their thinking. And the notion- that the UN’s resolutions on Kashmir are obsolete-holds no justification. The fact of the matter is that the UN Charter upholds the right of self- determination without compromising the political expediencies. It is why there are manifold UN’s resolutions on both Palestine and Kashmir.

The argument of ‘shared & international responsibility’ in international law

International law carries out the attribution of wrongful conduct pursuant to the agency theory, which operates en lieu of causation. The absence of causal analysis from the determination of internationally wrongful acts is the result of consistent State practice, based on a clear distinction between the national and international legal orders.

International responsibility is not domestic liability writ large; it is international accountability of international actors in the international community. The differences that international responsibility bears with domestic legal orders respond to the legal articulation of an international system of rules, distinct from the legal orders of the sovereign subjects it addresses. Given the logic of this argument of international law , the UNSC as well as India have to fulfill their ascribed roles of international responsibility vis-à-vis Kashmir dispute that causes great concern in international community.

Kashmir is an unfinished agenda of the partition of subcontinent. A solution to Kashmir is absolutely crucial to ensuring the integrity of both international law and international security on the subcontinent.