By Syed Qamar Afzal Rizvi.

Revisiting the Indus water treaty

The Pakistan Senate passed on Monday a resolution asking the government to “revisit” the 46-year-old Indus Waters Treaty on water sharing with India. “This House recommends that (the) government should revisit Indus Waters Treaty 1960 in order to make new provisions in the treaty so that Pakistan may get more water for its rivers,” says the resolution.

Many in Pakistan accuse New Delhi of wantonly exacerbating the country’s dire water shortages, choking its agricultural production and ruining livelihoods.

India’s Indus Water Commissioner G. Aranganathan says that after India fills its reservoirs in the initial stages of each project, it only uses the water it needs to run its turbines and doesn’t prevent any from flowing into Pakistan. “There is absolutely no question of interrupting or reducing Pakistan’s water supply,” he tells TIME.

What was the Indus water treaty about?

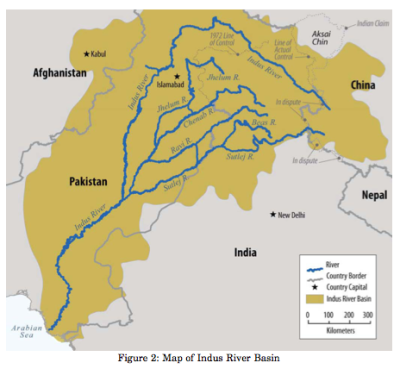

The Indus Water Treaty was ultimately signed in September 1960 when Prime Minister Nehru visited Pakistan. Following protracted and painstaking negotiations, both India and Pakistan signed an accord in 1960 called the Indus Waters Treaty that determined exactly how the region’s rivers are to be divided. In the treaty, control over the three “eastern” rivers — the Beas, Ravi and Sutlej — was given to India and the three “western” rivers — the Indus, Chenab and Jhelum — to Pakistan. More controversial, however, were the provisions on how the waters were to be shared.

Since Pakistan’s rivers flow through India first, the treaty allowed India to use them for irrigation, transport and power generation, while laying down precise do’s and don’ts for Indian building projects along the way. Indeed, India has ramped up its hydroelectricity projects in recent years to try to boost its woefully inadequate power supplies.

The Treaty grouped the five rivers of Punjab into two categories. The Eastern rivers: the Ravi, Sutlej and Beas; and the Western rivers: the Indus, Jhelum and Chenab. The waters of the Eastern rivers can be stored by India. As we know, these are being extensively used for irrigation and power supply to Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Harayana and Delhi. The Western rivers are available to Pakistan. India can only use their running waters but is not permitted to store those waters. However, it can use the Jhelum and Chenab for generating power, and store water on tributaries of the Jhelum and Chenab for irrigation or power supply. The Treaty was welcomed both in Pakistan and India.

The Treaty had an unstated quid pro quo: the resolution of the Kashmir dispute. It was then felt that the resolution of this issue would pave the way for resolving the J&K dispute.

The utilitarian deliberations vs. new realities

The reverberation of IWT in both aspects necessitates its detailed understanding. Anyone interested to understand the IWT and its allied issues in the language of foreign policy that is best expressed through vehicle of international law must read two short but conceptual articles: first is Hamid Sarfraz’s ‘Revisiting the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty’, and second is “The Indus Basin: Challenges and Responses by Erum Sattar, Madison Condon, et al. Besides, the 1997 “United Nations Convention on the Law of the Non-Navigational Uses of International Watercourses (UNWC)”, and “The Helsinki Rules on the Uses of the Waters of International Rivers,” 1966 may serve as a legal guide on the point as though UNWC is not yet in force, it does offer wisdom extracted from international water jurisprudence and may, at times, highlight principles of law that may be regarded as of customary international law value.

The IWT, determination by neutral expert in Bagliar Hydroelectric Plant in 2007 and partial award by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 2013 are, of course, must read stuff on the point. Fortunately all the material is just a google away.

The Harmon doctrine and Indian thinking

Lt. Gen (Retd) Eric A Vas in his article ‘Troubled Waters: Should We Revisit Indus Waters Treaty’ has acknowledged the impact of Harmon Doctrine on Indian thinking at the time of negotiations of IWT. This begs for understanding the Harmon Doctrine. Water has been essential for human existence since time immemorial. However, with the sophistication and evolution of human society, water got recognized as a resource. Its watercourses got more attention and the uses of those were divided into navigational and non-navigational by the end of late nineteenth century with former category regarded more valuable than the latter.

It is with the industrial revolution and advancement in technology that irrigation, hydropower and flood control became sources of progress, and the non-navigational value of water came at par with its navigational significance. This gave rise to riparian, utility and storage disputes of non-navigational waters.

“The fundamental principle of international law is the absolute sovereignty of every nation against all others, within its own territory.”

The mindset of India led to manipulation of its position and natural location. The ultimate result was apportionment of western and eastern rivers in IWT. Conversely, Pakistan’s viewpoint was based on a competing legal principle that transcended above the selfish and parochial Indian approach.

The legal principle of equitable and reasonable utilization, which is now the cornerstone of UNWC (Article V), was rejected by India. It may also be stated that the principle of equitable and reasonable utilization of watercourse was not an invention of UNWC, but was based on case law of international legal adjudicatory bodies as well as of Helsinki Rules of 1966. On the basis of equitable utilization principle, Pakistan was entitled to 90% of waters; however, it confined its claim to 75%, but with the domination of Harmon Doctrine, the rationalized equitable claim of Pakistan didn’t materialize.

The aforementioned research paper lucidly captures the essence of IWT in the following words: ‘…the two countries agreed to allow principles of engineering and economics to drive the process rather than using legal considerations.’

Although India is permitted to exploit the hydro-electric power potential of the Jhelum and Chenab, all Indian projects have to be vetted by the Pakistan Indus Commission which can exercise a virtual veto; this enables it to put conditions that are patently disadvantageous to India.

For example in the Salal Hydro Electric Project, Pakistan objected to the use of under sluices. This necessitated a change of design, which has resulted in very heavy siltation of the reservoir. Over the years, the silt level in this 113 m high dam has reached 90 m, and the 30 km long reservoir has shrunk to just 14 km. This would not have happened had the use of sluices been permitted. India was determined that this should not happen again.

Indian stand over its hydro- Projects

India says that the construction of projects is endorsed by the treaty and all projects are within the limitations of the Treaty’s criteria. India replied, citing the norms of the treaty and Indian experts have expressed frustration over long delays in approval of these projects due to objections held by Pakistan, as around 27 projects on the western rivers have been questioned by Pakistan.

Indian analysts and media are of the view that the provision of neutral experts should be the last option and not the recourse for each and every project that India proposes. The reference does cost time, money and efforts, in terms of delaying the projects, thereby increasing the cost of not only construction but also related expenditures in not making use of the hydro potential.

Pakistan’s concerns over Indian projects

First, Pakistan, as lower riparian has apprehensions over the projects such as Salal, Baglihar, Kishanganga, Wullar Barrage, Uri Nimo-bazgo etc. and it considers them as the existential threat to its inhabitants, as stored water can flush out the land and property. Secondly, Pakistan also fears that these projects will reduce the water flow in critical times, especially during the sowing seasons.

From a security point of view, some strategic analysts in Pakistan are of the view that the Indian intentions are directed towards flooding Pakistan during military action and that flood waters could destroy Pakistani defence. Pakistan has also certain economic and defensive apprehension on the construction of projects, especially on Jhelum and Chenab River.

In 2008, after filing of the Baglihar project and subsequent reduction of the water flow in Pakistan, the project has drawn serious concerns and gained critical attention in Pakistan’s political circles. With regard to Wullar Barrage, it has also incurred political and strategic voices from Pakistan, as it fears that with the construction of the Wullar Barrage in Indian Occupied Kashmir (IOK), India could close the gate of Wullar Barrage during a warlike situation, enhancing the ability of Indian troops to enter Pakistan.

The Revisiting vision & other examples

The question of revising unfavourable treaties has many global precedents. Hungary and Czechoslovakia had gone to the International Court of Justice [ICJ] over Hungary’s going back on a 1977 Treaty pertaining to the construction of a project on the Danube River. Interestingly, the ICJ gave its ruling not on the basis of the 1977 Treaty, but on a customary international law of sharing water resources in terms of “equitable utilization”. Apart from equality, there is the question of national interests. The USA has recently abrogated the Anti Ballistic Missile Treaty that it had signed in the 70s as it felt that it no longer conformed to the security compulsions and realities of the 21st Century.

Nevertheless, there can be little doubt that in order to offset population growth, improve agriculture and horticulture, and enhance the generation of power, every state has the right to revise old treaties and redefine what constitutes an equitable share.

(the Baglihar dam )

The bitter lessons for Pakistan

Deciding victors in two cases: the Baglihar dam and the Krashnaganga dam may not be healthy. Suffice is to say that the threshold of dispute avoidance under IWT has been crossed in both the cases as matters were ultimately not decided in the way they were decided since inception of IWT. Why Pakistan is in more trouble

The fact that, unlike India, all of Pakistan is wholly dependent upon the Indus River system is a geographical reality.

Another reality that compounds this one is the fact that, as the upstream riparian on all five of the main Indus tributaries that flow into Pakistan, India has the strategically advantageous position with regards to control and flow of water.

John Briscoe, a subcontinental water expert, former World Bank senior water expert and currently a professor at Harvard University, recognised Pakistan’s unhappy position in the following words: “This is a very uneven playing field. The regional hegemon is the upper riparian and has all the cards in its hands.”

Pakistan is all too aware of its vulnerable position vis-a-vis water and the fact that more than half of independent Pakistan’s time has been spent under military rule has not helped to de-escalate or ‘de-securitise’ the water discourse in the country.

Over the years, water has been raised as an issue directly linked to Kashmir. Pakistan’s political leaders and military elites have emphasised that if they are forced to let go of their claim to Kashmir, that will mean letting go of the source of Jhelum and Chenab as well and being at the mercy of India for water.

Though it is unrealistic to assume that India could readily and easily violate the terms of the Indus Water Treaty, John Briscoe, the Harvard expert emphasises that Pakistan and India do not have “normal, trustful relations”. The trust deficit along with the fact that India once blocked water flows to Pakistan has the military establishment convinced that they must hold on to their claim to Kashmir in an effort to maintain the country’s water security. “Even if it were assumed that some mistakes were made at some short period, which in any case did not exceed one or two weeks,” he said.

Throughout the history of the dispute, India has rarely, if ever, acknowledged that it has tampered with the supply of water flowing into Pakistan.

(Pakistan senate)

The argument why Pakistan should revisit the treaty

The nexus of foreign policy and international water law, if fully explored, takes it to the Kashmir dispute, where the ultimate control of the western rivers lies. Pakistan needs to introduce input of a highly specialized foreign service into its policy formulation as the challenges of the new and emerging realities in highly globalized world are necessitating fresh and erudite approach. As far as IWT is concerned, it is not a perfect document; as is the case with any treaty in the world. The shortcomings of IWT include its failure to address climatic variance, environmental considerations and insistence on water apportionment instead of coordinate management of natural resources as precious as watercourses of the two countries.